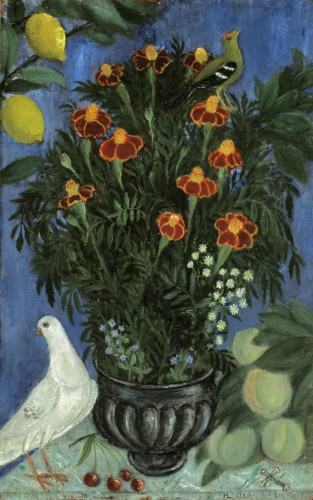

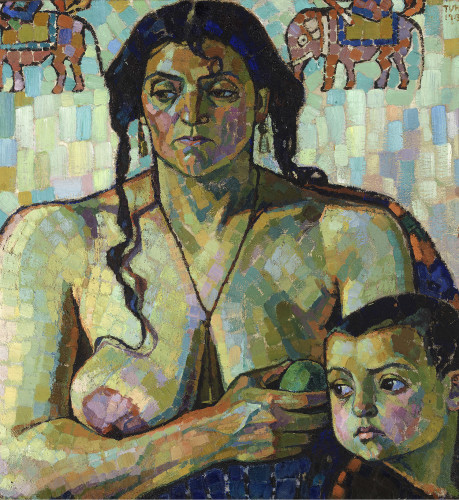

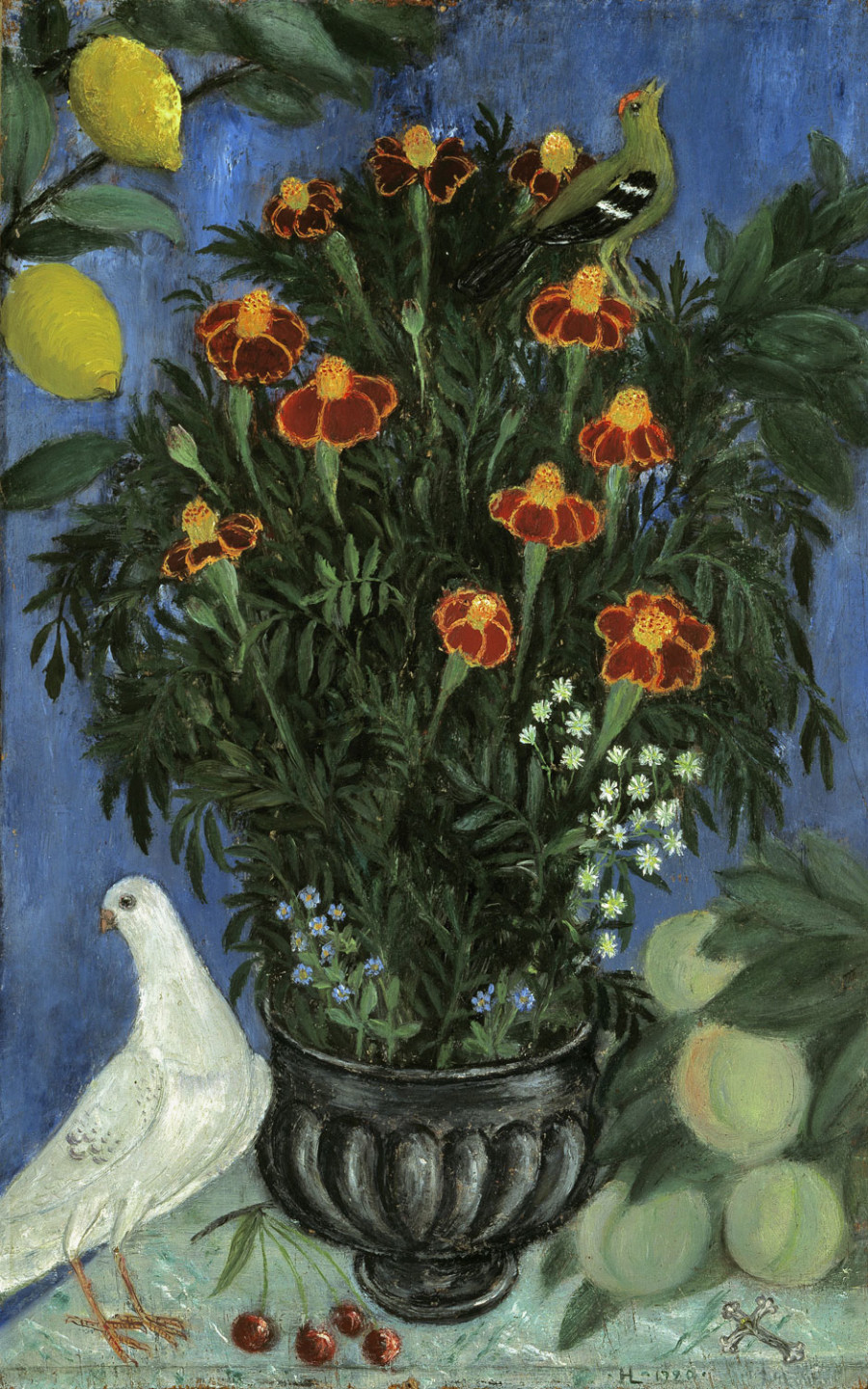

Tora Vega Holmström, Främlingar, 1913–14 Acquired with funds from the Second Museum of our Wishes, Moderna Museet. © Tora Vega Holmström / Bildupphovsrätt 2015

10 Stories

Swedish Art 1910–1945. From the Moderna Museet Collection

2.6 2007 – 9.9 2007

Stockholm

In the first decades of the 20th century, many Swedish artists went abroad to explore the formal idiom of abstract art. Most of these artists, however, reverted fairly soon to the narrative tradition. This exhibition looks at some ten “Stories”, themes such as meetings between human beings, cultures, ways of life and political opinions. The featured artists include Ivan Aguéli, Nils von Dardel, Siri Derkert, Sven X-et Erixon, Sigrid Hjertén.

Curator: Cecilia Widenheim

Portrait of the Times

So how is the story about the “modern era” told? A few of the more fascinating narrators of this period describe the public domain – street life, beer parlours, plazas. These are telling contemporary portraits of places where people and ideas meet. Others portray the unassuming spaces between town and countryside. In suburbs and industrial estates where the boundary between the new and the old is blurred, the artists of the inter-war period found new subject matter.

A completely different story is told by the artists who lived in exile in Sweden and who were considered “rare birds” throughout their lives. Two of these are Endre Nemes and Peter Weiss. Both took part in the exhibition Konstnärer i landsflykt (Artists in Exile) held in 1944 in a shack on Nybrokajen in Stockholm during the Second World War. Their detailed paintings in dark, ominous colours contribute a taste of Central Europe’s dramatic history to the Swedish welfare state modernism.

Humanity

The 1930s was a turbulent decade, with mass-unemployment and economic depression, and increasingly harrowing rumours of evolving dictatorships in Europe. The first to be silenced were the free artists. Touring Germany was the Entartete Kunst exhibition, in which the Nazi regime decreed what was good art and bad, degenerate, art. Parallel with the ethnic cleansing, a horrific aesthetic censorship campaign was launched. Artists, writers and other intellectuals had to lay down their tools, take flight or go underground.

The graphic portfolio Humanitet (Humanism), produced in 1933, and the magazine Mänsklighet (Humanity) from 1934 are two examples of hard-hitting Swedish anti-war satire. The artist Albin Amelin was fiercely committed to both enterprises. With generous assistance from painters, graphic artists and writers, he tried to rouse resistance against the censorship that was taking an increasingly tighter hold on society, including visual arts. For the Humanitet portfolio, produced with the printer Ruben Blomkvist and a group of young graphic artists, linoleum cuts were used by virtue of being a fast and inexpensive method. The magazine Mänsklighet was intended as an ongoing publication, but only two issues were produced in 1934, due to difficulties with distribution.

The following year, Bror Hjorth was stopped by censorship. His lovers compositions, exhibited at the gallery Färg och Form in Stockholm, were reported to the vice squad. The artist was forced to remove several works from the exhibition, on the grounds that the subject was indecent in a public space.

Travelling with a camera

In the first decades of the 1900s, modern photo journalism began to develop in daily papers and magazines, and photographers gained a more crucial role in documenting the old and new Sweden. Three photographers who specialised in travel photography for a period of their lives are presented here.

Anna Riwkin’s studio was in the building on Kungsgatan in Stockholm where Elise Ottesen-Jensen (Ottar), pioneer of sexual education, worked. In 1938–39, they travelled north together. Riwkin’s photo feature shows Ottar in northern Swedish villages and small towns, lecturing charismatically on the right to legal abortion, relationship issues and contraceptives, before jumping into the car and driving on.

Carl Gustaf Rosenberg travelled around Sweden taking photographs on behalf of the Swedish Tourist Board (STF) for nearly thirty years. The series from the counties of Skåne and Halland is a beautiful voyage in black and white through billowing, idyllic countryside. Here and there, the modern era breaks through, in the form of a power station development or an elegant group of golf-players.

Sven Järlås was one of the most prolific press photographers of the inter-war period. In 1939, he visited the World Exposition in New York, where as many as 60 nations participated under the motto of Building the World of Tomorrow. This feature contrasts sharply with the documentary project Ålderdom (Old Age), which Järlås undertook together with the author Ivar Lo-Johansson a few years later. This dismal portrait of the state of geriatric care in the mid-1940s became famous as Sweden’s first photographic indictment.

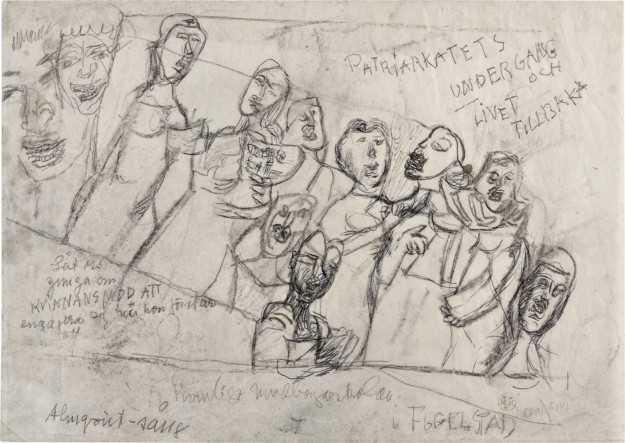

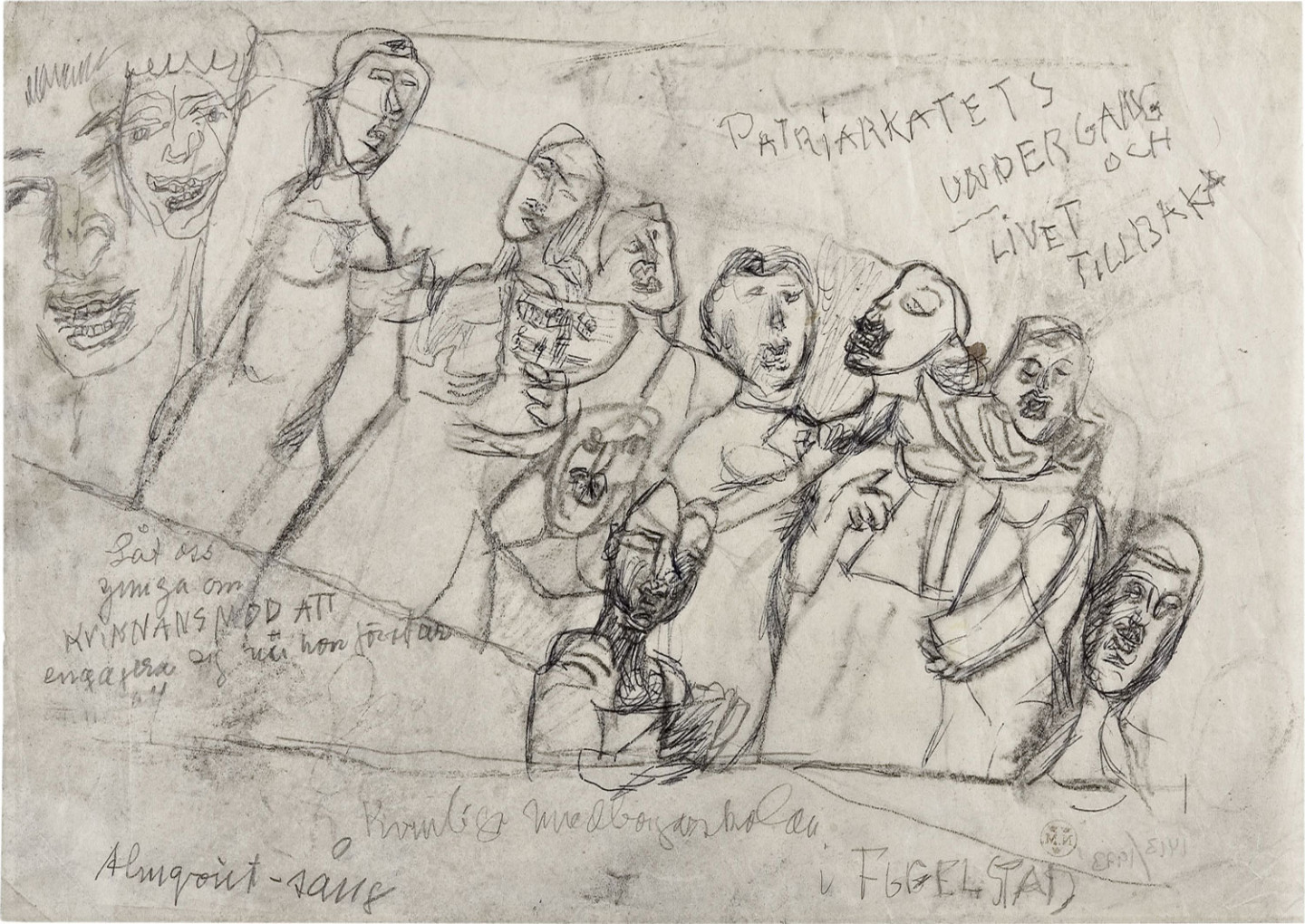

Report from Fogelstad

The Women’s College for Civic Training at Fogelstad was founded in 1925 and continued to operate until 1954. It was open only for women and was started on a private initiative, attracting several of the women behind the radical weekly magazine Tidevarvet (The Era), along with many prominent cultural representatives, politicians, writers and intellectuals as Ada Nilsson, Emilia Fogelklou, Alexandra Kollontay, Elin Wägner, Hagar Olsson, Kerstin Hesselgren, to name but a few.

The estate owner Elisabeth Tamm was one of the initiators and put her manor house in the county of Södermanland at the disposal of the college. Her friend Honorine Hermelin took on the position as principal. The curriculum included the major issues of the modern era – the development of democracy, social policy, feminism and peace – mixed with outings, choir singing and exercise. The idea was to foster independent, free-thinking citizens. The Swedish author Moa Martinson describes her time at Fogelstad in the following words: “Here, new strata in my brain were put to work.”

Siri Derkert came to Fogelstad for the first time in 1943. During her sojourns she sketched constantly. Her portraits were regarded as brutal caricatures by many, not least by the models themselves. Today it is obvious that Derkert regenerated the genre of portraiture, while finding a new, fertile road in her own development as an artist. Twenty years later, she used the portraits and the ideas from the college in her large concrete etchings that now adorn the Östermalmstorg underground station in Stockholm – a 145-metre long tribute to the women at Fogelstad.

Strangers

This story was named after Tora Vega Holmström’s painting Strangers from 1913. The woman and child were part of a group of Italian guest workers in the Stockholm Harbour. The German author Rainer Maria Rilke, with whom Tora Vega Holmström corresponded, said her painting epitomised the state of the world, characterised by rootlessness and an uncertain future.

The year Strangers was painted, Siri Derkert and Ninnan Santesson travelled to Algeria to work. Shortly after, the First World War broke out and the borders were closed. The inter-war period was a new time for travelling. Many people went on the classical grand tour through Europe. Others went further afield, to the African continent, or eastwards, to Asia.

Interior photos from the first decades of the 1900s give an idea of the strong oriental influence on the era. The studios are filled with exotic objects and oriental carpets brought back from long voyages. People socialised on divans, sipping tea out of glasses. The most interesting travellers sought to widen their views both geographically and artistically. One of these was Ivan Aguéli.

Round about 1913, Aguéli resumed his richly luminous style of painting in Egypt, where he had been before to study Arabic and Eastern philosophy. Abdalhadi, as Aguéli called himself, was no ordinary tourist with an easel tucked under his arm. He converted to Islam and fought throughout his life to consolidate his disparate interests in modern art, anarchism and Arabic literature.

Visit to an Eccentric Lady

Nils von Dardel is one of the most fascinating storytellers of Swedish 20th century art. In 1910, he went to Paris to study at Matisse’s academy, and was soon part of the circle around Braque, Picasso, Cocteau and Apollinaire. Rolf de Maré also became one of Dardel’s closest friends, and Dardel designed the sets for several of Les Ballets Suédois’s acclaimed productions under de Maré at the Théatre des Champs-Elysées.

Dardel’s pictorial world is resplendent with associative and dreamy elements. Eccentric characters gather in exotic rooms where absurd little scenes unfold in shimmering hues. The moods oscillate between desire, anxiety and death. Dardel skilfully incorporates the penchant for various kinds of orientalism at the time; tourism, for instance, was a growing phenomenon. Until his death in 1943, Dardel led an itinerant life, travelling to Indonesia, the USA, Cuba, Japan, North Africa and the Canary Islands.

The Dying Dandy is reminiscent of the fascination in the 1910s for gender-bending, for queerness. In Parisian artist circles, the dandy walked alongside the boy-girl, the garçonne. In the sketch for this famous painting, Dardel grouped an all-male crowd of mourners around the dying young man. In the painting two of them are exchanged for women. The only man among the mourners has the role of crier.

Song of the heart

Could there be anything less eventful than a floral still-life or the picture of an empty room? Paradoxically, an uneventful story can be very dramatic and thought-provoking. The absence of characters or a clear narrative prompts the viewer to ask what has just taken place, or what is about to happen.

This room is named after Hilding Linnqvist’s painting Song of the Heart, painted in 1918. Linnqvist’s style of painting flowers is entirely different from the expressionists’ more decorative line painting. “Flowers are tricky to paint,” Linnqvist once exclaimed, “they wither and if they are finished you have to wait for a whole year before you can finish the painting.”

Einar Jolin paints his models as if they were jewels or beautiful objects that are exquisitely displayed in his cool paintings. The objects he lays out in his still-lifes seem made to be relished like fruits. Between them secret stories evolve in silence.

In Eric Hallström’s intimate painting, a vase with flowers stands on a table in a dark room. The vase reveals a landscape with a church. Through the window we can look into yet another world. Hallström builds an intricate interplay between different perspectives that appear to interlace different moods and memories.

Portraits of friends and self-portraits

Portraits of friends has long been a favourite genre among artists. With a friend or colleague it is possible to try out new styles, techniques and expressions, without putting too much at stake. Isaac Grünewald painted Ulla Bjerne, Vera Nilsson painted Siri Derkert, Sven X-et Erixson painted Bror Hjorth and Hugo Zuhr painted Astrid Noack.

The portraits in the style of die Neue Sachlichkeit are in subdued colours, and the atmosphere of the room appears to be just as important to the artist as the depiction of the person. One exception is Tyra Lundgren who enacts herself – as neither man nor woman. If we study the portraits featured here from a gender role perspective, we discover a number of interesting attempts to explore, and also to dissolve, the traditional male-female stereotypes in art.

The self-portraits reveal to us the artist’s own self-perception. One’s own face is, of course, the cheapest and most readily available model for an impoverished artist. But the self-portraits also have something to say about the artist role and the artist’s approach to his or her work.

A series of works from the 1920s and 30s, shows Vera Nilsson’s daughter Catharina taking her first steps, writing, reading, drawing or just staring out through the window at dusk, daydreaming. The artist evokes an intense sensation of a mood and frame of mind, of the details of the “little life”. It is universal and hypermodern at one and the same time.

Behind the red blind

Sigrid Hjertén is one of the key figures in the story of the breakthrough of modernism in Sweden. Her works continue to fascinate new generations of art viewers. Early in her career, her expressionist paintings encountered strong criticism. There was a high price to pay for breaking against traditional art values, and the paintings by Hjertén and her colleagues were called “works of madness”. Her way of combining an ultra-modern palette with psychologically complex subjects is still regarded as innovative.

When Sigrid Hjertén travelled to Paris in 1909 to paint at Henri Matisse’s academy, she had already completed studies in textile art. Her international debut came at an exhibition in 1915 at Herwarth Walden’s radical gallery in Berlin, where Sigrid Hjertén’s rather daring colour scheme was much-admired by the German expressionists. Soon her self-portrait adorned the cover of the legendary magazine Der Sturm.

Can the story of Sigrid Hjertén’s art be told without telling the story of her life? Like many women artists, Sigrid Hjertén fought hard to cope with her different roles – as a mother, a wife and a professional – and a modernist. Recognition from the broader public did not come at once. When her first solo exhibition opened in 1936, she had already been for some time in a mental institution and was too ill to attend the opening.

Under the fruit tree

Perhaps the urge to depict an idyll is stronger than ever in turbulent times. Eric Hallström’s painting A Summer’s Day in Haga is signed 1918–19. The summer landscape appears blissfully ignorant of the First World War that has just ended.

Ragnar Sandberg’s painting Under the Fruit Tree has lent its name to this story, which, at first sight appears to be light-hearted. The paintings are about summer, sunshine and the play of light through leafy branches. Sven X-et Erixson takes us to a lively beach, Hilding Linnqvist has captured children in a summer meadow.

Anna Casparsson’s embroidered screen takes the step into the world of fairytales. Here, any means are permitted in the endeavour to tell the legendary stories. Casparsson mixes painting, embroidery and collage and embellishes with beads and pebbles. The less known artist in this genre is perhaps Mollie Faustman, better known under her pen name Vagabonde, with which she signed her articles in Idun and other magazines.

A common trait of these artists is that they were all skilled colourists. In liberating the colours they found new roads and means of expression, and thus, new visual perspectives on the world. Ragnar Sandberg, who is regarded as a representative of Swedish colourism, navigates deftly through ambient landscapes where the subject appears inseparable from the colours and composition.

The exhibition is supported by

![]()