Ivan Aguéli, Egyptian Domed House, 1914 Photo: Juan Luis Sánchez/Moderna Museet

Depth

“Portrait of the Times” portrays an era when the gap between urban and rural-agrarian life was widening, as farm workers migrated to the factories. We are treated to stories from travels and contacts with foreign cultures in “Strangers”, named after Tora Vega Holmström’s painting of Italian guest workers in the Stockholm Harbour in 1913. Nils von Dardel’s worlds populated by the most fascinating and bizarre characters unfolds in “Visit to an Eccentric Lady”. A partially different story is told by the artists who live in exile in Sweden. And then, of course, we meet the artists behind the stories in “Portraits of Friends and Self-Portraits”, which presents their perception of themselves, their approach to art and the role of the artist.

Hilding Linnqvist

In a Park, 1918

© Hilding Linnqvist/BUS 2007

So, what is the story of the modern? On closer inspection, what we call “modern” comprises countless disparate approaches. The reactions to the progress of modernity can be entirely different, depending on whose perspective we choose. When Moderna Museet showed the exhibition Utopia and Reality a few years ago, Swedish modernism was revealed to be lyrical, a statement that invites further explorations. 10 Stories focuses on local variations or parallel versions. Along these narrow tracks running alongside the wide thoroughfares of the avant-garde, we find a myriad of fascinating voices – from civilisation critics to anti-modernists and lyricists. The ten themes or chapters that form the structure of this exhibition each have their own narrative style and technique. Each theme heading is borrowed from a work of art in the exhibition.

Some works are like folksongs. Others have a note that evokes personal experiences and memories – for instance, “Report from Fogelstad” – Siri Derkert’s sketches from her sojourn at the women’s college in Fogelstad. “Travelling with a Camera” presents modern photo journalism from the period. Examples of art with a concrete political message and art that comments on the role of art in society are shown under “Humanism”, reflecting Europe in transition, a world where political systems, beliefs and aesthetic tenets were being tried and challenged, discarded and regenerated. Contrasting with this incendiary material, we have “Song from the Heart” and “Under the Fruit Tree”; the latter a story that borrows its name from a painting by Ragnar Sandberg, where the light filters gently through the branches of a green tree. Last but not least – when we approach art from the inter-war period and seek to find the most interesting narrators, our searchlight falls on the women artists. Thus, a whole chapter is devoted to Sigrid Hjertén, titled “Behind the Red Blind”.

All the works in 10 Stories are from the Moderna Museet collection of paintings, drawings, sculptures and photography. The selection is based on the idea that a museum collection can never be fully described by one voice, or one pair of eyes. A museum collection contains several parallel, and often contradictory, stories. No matter how we choose to define the material and its interest to a contemporary visitor, however, it is true to say that it comprises our common visual heritage. Some of the works are by our most famous and loved Swedish artists. Others have, for one reason or another, fallen into oblivion.

Portrait of the times

The inter-war period was a time for reflection. Europe was going through turbulent changes and perhaps needed its stories more than ever. On the Continent, there were ideas of returning to order – le rappel à l’ordre – as the French author Jean Cocteau put it in the 1920s. After the horrific First World War, and in the wake of the more avant-garde phase of modernism in the 1910s, art was moving toward greater classicism. Soon, however, a second wave of expressionism moved through an increasingly unsettled Europe. What had previously been called realism was changing. Realism in the sense of depicting reality changed, and even lost its meaning in some artist circles. The temperature in figurative painting was heightened by an expressionism that asserted the voice of the individual as Europe was increasingly racked by mass-exodus and authoritarianism.

Sven X-et Erixson’s famous painting Portrait of the Time from 1937 has lent its name to this chapter. This is a compelling picture of the Zeitgeist, but also an urban story set in the public domain where people meet and exchange information, a third space, in today’s cultural-political terminology. This includes bars, pubs, cinemas, museums and also plazas, avenues and narrow streets.

Art from this period launches a wide array of new subjects that mirrored contemporary everyday life. Gösta Sandels painted his Food Line in 1919, the year after the War ended. A group of people in grey-black full-length clothes are gathered outside a shop. To the right, a man in uniform. Most of the figures are women, and they are queuing for food. But paintings of public spaces by women artists are rare. The manifestations and rituals of the physical urban space is most certainly defined by men. Sigrid Hjertén’s urban landscapes are nearly always painted from above, from the window of her studio. The woman artist is an onlooker, not a participant. Vera Nilsson’s and Agnes Cleve’s city paintings from the 1910s and 1920s appear as radical and unusual exceptions.

X-et’s work is full of stories about a place or the atmosphere in a space. His painting of the outdoor dance in Telemarken is full of fumbling hands, clogs and longing. Portrait of the Time is set in Slussen, Stockholm, in the 1930s, where a few lonesome figures gather to read the latest world headlines on the news bills. X-et takes us on a tour of the carefree welfare state, to places that smell of summer and sunshine, but he also grapples with portraits of the dire 1930s depression, unemployment and life in the shadow of a barbarous civil war. Emond, who grew up in Scania, southern Sweden, did not set off for Paris like many of his contemporaries, but chose Berlin instead. Here he found the theme for his Variety Cafe at Closing Time (1938), a lugubrious scene. The artist captures the minutes before closing time, with a few lingering guests enveloped in thick clouds of cigar smoke.

A scene that is also associated with the melancholy of urbanisation is the suburb. Here, another intriguing side of the third space reveals itself as an interpretative model, where the third space stands for the state of neither-one-nor-the-other, an in-between zone. Many of the artists featured here found their subject matter on the outskirts of the city, in the grey zones that developed between the city centre and the industrial or domestic areas. In these places, which had not attracted much attention from urban planners, small industries began to sprawl between vacant lots and more or less temporary shacks for housing. This landscape, which Ivar Lo-Johansson described as “suburbian half-nature”, provided artists with new themes, culled from the unglamorous “space” that links city and countryside, the old and modern Sweden.

The style of reality

The eschewing of academic painting appears to have been linked with the move from the centre of the city and the art scene. Hilding Linnqvist and a few other artists had walked out from the Royal Academy in 1912 because they considered the instruction there to be antiquated. But they didn’t walk far. They found a temporary haven in the area around an old mansion on Kungsholmen in Stockholm. The Västerbron bridge had not been built and the house out on Smedsudden became their pastoral retreat. They turned their backs on what they perceived as ingratiating and decorative in the new art trends from Paris. “Matisseries”, Hilding Linnqvist is said to have muttered. Above all, they wanted to reclaim narrative art – not the 19th century moralising stories full of patriotism and pompous history, but the quiet chamber play of ordinary life, real-life stories.

The paintings that were created in this circle are often small and have a lyrical note. Avoidance of the grand gestures of academic painting became their lead motto. Better to be autodidactic, earnest and inept than to be technically skilled and urbane. This intimate style of painting later came to be called naivism. Eric Hallström decided in 1918 to paint the New Year’s celebrations at the outdoor museum Skansen. The ancient figures of pagan mythological rituals crawl out from the nooks and crannies as darkness settles on the snow-covered buildings out on Djurgården. The rituals of old Sweden are enacted for a well-dressed urban audience. When the so-called “naive” artists were asked who they admired and where they found their inspiration, their replies show a telling absence of international modernists. Instead, they mention the “rural painter” Pehr Hörberg, the 19th century artist Ernst Josephson’s paintings from his insane period, and poets such as Stagnelius, Fröding and Almqvist. But back to the 1930s and the style of reality: “If I were to find a phrase to describe my striving, it would be the style of reality. What inspires me is the remarkable real life.” Siri Derkert’s statement on her artistic convictions has often been quoted and is based on a very distinct standpoint. It is fundamentally about not confessing to a particular style in the contemporary sense, but to an approach, a way of looking at art. Of demonstrating detachment from the content-denying art that propounded the intrinsic value of colour and form, independent of content.

The narrators of 1920s and 1930s art are often not contented with merely documenting an event; instead, the event seems to merge with the narrator’s life. The essential point was to stop differentiating between life and fiction. Now, the dominating concern was the interaction between insight and interpretation, between creating images and depiction. But also between fantasy and reality. On the west coast the Halmstad Group embarked on their own unique interpretation of realism in their dream-like style that has come to be associated with surrealism. But that is another story.

Encountering the unknown

The inter-war period was also a time for travel and intensified cross-border exchanges in the field of art, after a period of isolation. The documentation of these travels, however, is mostly hidden away in sketchbooks. Sometimes, a footnote at the end of a biography is all that remains of a pivotal influence on an entire oeuvre. Perhaps this is due to the conventional division into genres, or the result of a strictly modernist approach to art. As if the works inspired by travels were less important than those with more independent subjects. And yet, both the visual arts and literature would be impossible without travel. So what did these travels lead to? Was travelling the vehicle for new ideas, or did travelling merely confirm old inherited (mis)conceptions about the unknown? The voyage as an exotic subject, as an exoticising subject. The mind boggles.

The most interesting voyagers seem able to widen both their views and the concept of art.

One of these is Ivan Aguéli, an artist from Sala whose geographic and philosophic excursions continue to fascinate generations of audiences. He reminds us that the theories of modernism caused a polarisation of centre and periphery.

The early avant-garde artists had posed the question of whether the future of art to some extent lay in what the western world called “primitive” and “untrained”. The cubists, headed by Picasso, did not, after all, find their inspiration in the halls of the Louvre but in the ethnographic museums with their collections of African and other non-European sculptures. Or, as Isaac Grünewald said in a lecture in 1918: “The expressionists felt that they must create a new language, clean their palettes and change their drawing utensils. They were on new territory, they were primitives.” Nils von Dardel, Siri Derkert, Ninnan Santesson and Tora Vega Holmström are a few of the artists who, like Aguéli, shunned the grand tour of classical art through Europe and instead ventured down to the African continent or east, to Asia.

Photographs from the early decades of the 1900s, give us an inkling of how strongly the era was dominated by orientalism. The artist studios are filled with exotic objects, oriental carpets and Chinese paintings. They gather to drink tea and play cards, lounging on divans. The story of the east is vivid in the imagination, where the west stands for the modern, enlightened and rational in contrast to its opposite, the sensual, exotic Orient.

In some circles, this penchant for non-European cultures had a strong impact that went far beyond interior decorating. In an article on “Modern and Eastern Art” which Sigrid Hjertén wrote for Svenska Dagbladet in 1911, she emphasises the common ground of modern painting and non-European art: “The same qualities that we admire in the Chinese and Persians can be found in a Cézanne, a van Gogh. The distinguishing characteristics that are thus shared by our most modern painters today and the men of the thousand-year empire can be traced back to the elementary laws, which, when they are embraced by a great or unique personality, have formed the paragon for our most intense striving.” The subject inevitably leads to the issue of Europe’s own “Orientals” – the Jews, Romany and women – a marginalisation that affected both Sigrid Hjertén and Isaac Grünewald, who was persecuted as an “Oriental” and and “express Zionist”. Contemporary scholars have discussed whether Sigrid Hjertén was also the victim of a form of orientalism when she enacted herself as an exotic woman and a mother. Were those the only roles available to her in the male-dominated modernist art scene, that enabled her to participate, albeit as “the other”, the exotic, the female? The role play in her painting Studio Interior from 1916 does suggest this idea.

Sven X-et Erixson was one of the most avid travellers among Swedish artists at the time. Enthusiastically and with indefatigable energy he painted the vivid street scenes of southern Europe. His first journey was in the mid-1920s, and he managed to visit many countries, including Spain, France, Yugoslavia, Austria, Morocco, Italy and Portugal, before the war closed the borders again. But he also travelled around northern Sweden and Lofoten in Norway, and it is interesting to ask how much these travels influenced his oeuvre. Ulf Linde comments on this in an essay written for Moderna Museet’s X-et exhibition one year before the artist died: “It was not the unknown, the exotic, that prompted him to travel abroad – it was the sun, the sky, the light, the soil, the greenery, the people – fundamentally the same everywhere. Perhaps one could say that he travelled to see all the elementaries from a new perspective – as when a sculptor walks around the model.” The first modern travel books, by Gide, Byron and Mandelstam, also appeared in the inter-war era. A new kind of travel also evolved, unlike the traditional exploits of diplomats and explorers. The Vagabond arrived on the scene, as a subject and an existential role model. Harry Martinson creates the idea of a global nomad after his time at sea. Lubbe Nordström travels abroad to “become a human being”. Both the physical, geographic and the imaginary adventure develop into an artistic style.

Art and politics – what would the world be like without art?

During the inter-war era, a new phenomenon emerged: that of painting about, writing against, and creating exhibitions for something or someone. But the idea of putting one’s art in the service of various causes was controversial. The cultural establishment did not appreciate artists who openly expressed their political commitment. This was regarded as unfitting. Peter Weiss, active as a writer, dramatist and visual artist in Sweden from the late 1930s, expressed this as two parallel forces: the artistic vision that is vital in changing human awareness, and the political force that intervenes actively and changes a situation. He emphasised that the two forces must meet – they cannot exist independently.

Who, then, had the interpretative initiative in a cultural climate tottering between the old and the new, where the chasm between aesthetic idealisation and warped expressionist bodies was rapidly widening? Expressions that disturbed the conventional image of the “fine arts” were publicly derided. There are countless examples of this. Bror Hjorth’s Fröding portraits were dismissed as “negro gods”. Anders Wahlgren’s film Sigrid & Isaac (2005) reveals the overt anti-Semitism to which many artists in Sweden in the 1910s and 1920s were subjected. The exhibition 17 Kvinnor (17 Women) at Liljevalchs Konsthall in 1917 caused male critics to use invectives such as “insane”, “unoriginal”, “perverted”, “pastiche”. Sigrid Hjertén, Siri Derkert, Vera Nilsson and their colleagues took cover, but many gave up.

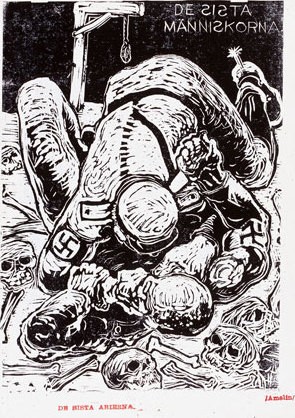

Albin Amelin

De sista arierna, 1933

© Albin Amelin/BUS 2007

But let us take a closer look at the pivotal year 1930. In Stockholm the great Stockholm Exhibition was a triumphant success. Social planners and proponents of the new architecture drew up visions of the future for the denizens of Sweden. Ivar Lo-Johansson’s description of his visit to the exhibition area is a veritable masterpiece in lucidity. The “sun of the new decade” shines down on his head. “Around me in the crowd people spoke of the new architecture that would engender the new feeling of life.” But where was the new human being? The proletariat writer’s words reverberate forebodingly between the whitewashed facades of the modernist buildings that stand there as blank and unwritten as the future. In hindsight, we know the answers to Ivar Lo-Johansson’s questions about the new face of humanity: National Socialism in Germany, Franco’s Spain, Stalin’s Soviet Union and Sweden under the compromising flag of neutrality.

Another of the many fascinating stories from Sweden’s cultural history is found in Ivar Lo-Johansson’s novel Tröskeln (The Threshold), in a scene describing a conversation some time in the 1930s between Albin Amelin, Sven X-et Erixson and the author. They talk about the reasons for art, about what can actually be “accomplished with literature and art”. Lo-Johansson propounds “tendentious” art, in the sense that art should primarily serve as a politically radical instrument. Sven X-et Erixson feels impelled to defend the right of art to be art – “Let the writers take care of that tendency!” Cézanne’s way of painting lemons was revolutionary in itself. There is only revolutionary form, no revolutionary content. If Albin Amelin were asked, he naturally replied that he was a socialist, but first of all he was a painter. Yet, he found most of his subject matter in the world of poverty and violent crime. The Miscarriage, The Last Aryans, Fallen Soldier, Murdered Woman – the titles of Amelin’s works from this period stated clearly what contemporary issues he wanted to highlight in his art. Social injustices, the inhumane life conditions of industrialism, and Woman, trapped between the mills of morality and production, who has to pay the price, again and again, with her body.

”Art will soon be public property”

When then minister of education and ecclesiastical affairs Arthur Engberg made this visionary statement in 1937 from the stronghold of social democracy, the time was obviously ripe to institute a Public Art Council. The public space was to be embellished with art. Art should no longer be a luxury item for the privileged classes but incorporated in the great welfare state, hopefully contributing to popular education. The ensuing discussion over the following years on aesthetics and its purpose as a regenerator of society is interesting in several ways. Behind the words about educating the people, about art in the service of society, and the autonomy of art, the prevailing ideologies of the era can be discerned. The state’s role as patron and commissioner of the arts became more openly declared. The inner circles of the newly-founded National Public Art Council included the group of artists that had opened the gallery Färg och Form a few years earlier. Despite their frequent and long sojourns in France, they are still seen as epitomising a typically Swedish style. The Swedishness perhaps also lies in the way they worked together. In defiance of the economic fluctuations in the 1930s art market, they started an artist-run gallery that sold its own art. The common denominators were everyday themes, a lyrical earnestness and one foot firmly planted in the Swedish welfare state. The reverse side of this is the stories told by the exiles who had fled to Sweden in the 1930s. Artists such as Endre Nemes and Peter Weiss had to learn to navigate between several political, not to say aesthetic, systems, and between two or more languages. The fate of these artists illustrates art’s role as a symbol for freedom of speech. The number of fleeing intellectuals was escalating, as many countries in Europe were restricted by censorship and aesthetic cleansing. In Germany several exhibitions toured with the purpose of pointing out what was good and bad art, so-called entartete Kunst. In the Soviet Union, social realism was the authorised style of the regime in the early 1930s. Totalitarianism was spreading. The independent artists were the first to be silenced, and the most crucial question of all was left hanging in mid-air – what would the world be like without art?

The debate around an exhibition in Stockholm of works by artists in exile in 1944 gives a vivid picture of the nation Peter Weiss fled to. The exhibition, Artists in Exile, was held in a temporary building on Nybroplan in Stockholm to benefit artists who were in Sweden as exiles. The participants listed in the catalogue include Lotte Laserstein, Endre Nemes, Peter Weiss and Egon Möller-Nielsen. A total of 50 artists were featured – Czechs, Poles, Hungarians, Germans and Russians, but also Danes and Norwegians. In spring 1944, a heated debate broke out in the press, where the exhibition jury was accused of undemocratic policies. The press also spoke of an “art dictatorship”, and called the gallery a “charity shed”. The tone of the reviews also reveals anti-Semitic and nationalistic attitudes, and there were speculations that “Jewish artists were trying to profit at the expense of others”. In Folkets Dagblad suspicions were cast over the whole idea behind the project, while German cultural policy was upheld as a good example. “The real artists in foreign countries do not flee from their country, but stay there and practise their art.” The article ends by encouraging Swedish citizens to buy Swedish art. Two years after the National Public Art Council was founded, Sweden introduced a ban on importing “inferior art” The ban, which lasted until 1953, was aimed at preventing bad quality in the field of art and protecting Swedish artists against unfair foreign competition. As the economic historian Martin Gustavsson points out in his thesis Makt och konstsmak (Power and Aesthetic Taste), the economic forces were one of the primary reasons why artists were driven to ally themselves with the government in the 1930s. But politics also played a part in this. In Sweden, the inter-war period modernist-inspired popular art was indirectly appointed as the government norm. At the same time, an idealising, so called “healthy” art style was appointed the national norm in Germany.

The visual narrative in the modern era

In the first decades of the 20th century, modern photo-journalism underwent a rapid development in daily papers and magazines, and photography played an essential part in exploring the old and new Sweden. The exhibition 10 Stories presents three photographers who specialised in travel documentaries during a period in their oeuvres.

The photographer Anna Riwkin had a studio in the same house on Kungsgatan in Stockholm as the famous pioneer in sexual education in Sweden, Elise Ottesen-Jensen (Ottar). In 1938, they travelled to northern Sweden together.

Anna Riwkin

Elise Ottesen-Jensen (Ottar)

© Anna Riwkin

Anna Riwkin’s camera captured Ottar lecturing in tents in northern villages and towns. The pictures show her speaking with gusto about free abortion, sexual relations and contraceptives, and hopping into her Chevrolet before driving on. Carl Gustaf Rosenberg travelled and photographed on behalf of the Swedish Tourist Association (STF) for nearly 30 years. He journeyed from south to north, and the yearbooks of the STF chronicle his progress, first by bicycle and later by car, through Sweden in the 1920s and 1930s. The photographic suite from the counties of Scania and Halland are a wondrous voyage through billowing, idyllic countryside. Farmers still inspect their crops slowly on horseback. Here and there, modernity breaks through in the form of a power station development, an elegant group of golfers in Båstad, or a snapshot from Bulltofta in Scania where the German Luftwaffe’s swastika-emblazoned airplanes stop off on their route.

Sven Järlås was one of the most prolific press photographers of the inter-war period. In 1939, he visited the World Exposition in New York. President Roosevelt opened the event, where as many as 60 nations participated under the motto of Building the World of Tomorrow. Contributions from Germany and Spain are conspicuously missing. Before the exposition closed, Hitler had invaded Poland and the state of the world changed overnight. A few years later, Järlås embarked on a major documentary project together with the author Ivar Lo-Johansson, who also later collaborated with Riwkin, Tore Johnson and Gunnar Lundh. Thus, the first “social photo book” came into being. Järlås’s project with Lo-Johansson was to document the situation for the elderly in Sweden. It contrasts brutally with the World Exposition in New York. The dismal photo-reportage on the care of the elderly in the mid-1940s became known as Sweden’s first photographic indictment.

The small life and the big issues

What new and old hierarchies dominated the art scene? Under the heading “Portraits of friends and self-portraits”, we find the artists’ versions of themselves and other artists. The self-portraits recount the struggle for an inner voice. The artist chooses a setting in which to reflect his or her self and occasionally to discuss the role of the artist. Sigrid Hjertén’s large painting Studio Interior from 1916 appears to harbour both the battle for space and the battle for the privilege of interpretation. Together with The Red Blind from the same year, it provides a key to understanding Hjertén’s entire oeuvre. The image of a frustrated woman and social complexity is channelled through Hjertén’s fragmented self-image and completely fearless colour range.

Vera Nilsson’s Stories and Lamplight are from a long series of works created in the 1920s and ’30s portraying her daughter taking her first steps, blowing bubbles, writing, reading, drawing or staring out the window at nightfall, daydreaming. Vera Nilsson carefully avoids conveying a message via the people she portrays. With colour and form she instead engenders an intense feeling of presence, a mood, a state of mind and the details of the “small life”. Human and hyper-modern.

When interpreting these portraits of friends and self-portraits it is useful to regard them from the perspectives of class and perceptions of the artist’s role in society, but they also reveal fascinating stories about men and women. About gender. Siri Derkert’s works from the women’s college in Fogelstad takes the art of portraiture far beyond depiction or idealisation. The sketches lend themselves to being read as a visual reportage from a voyage, one of a highly personal nature. Siri Derkert went to Fogelstad to “learn about politics”. And it was the really important issues that were debated there – patriarchy, war and peace, feminism and social policy.

Tyra Lundgren

Självporträtt

© Tyra Lundgren/BUS 2007

In one drawing, someone is quoted as saying that women commit fewer crimes than men but still have to pay as much to the police force. And their state pension is lower too. In another sketch, Derkert has written the following ominous question in large letters: “When does rape start?” The question is not “if”. Fogelstad attracted women who came to listen to women lecturers, and in the barn women agricultural workers tended Elisabeth Tamm’s cows. Is not this yet another attempt to create a “third space”, there at the country seat in Södermanland.

The dynamite of modernity

Siri Derkert, Vera Nilsson, Anna Riwkin, Ninnan Santesson, Tyra Lundgren, Mollie Faustman alias Vagabonde, Agnes Cleve, Sigrid Hjertén, Tora Vega Holmström. Against the backdrop of these women’s artistic radicalism and personal life stories, there is further reason to mention the concept of a third space, to bring attention to a key element in the situation of these women modernists, namely the experience of being in a void between systems. And their desire to formulate a third alternative, their own way.

If we study the ten stories from this perspective, we discover several interesting attempts to scrutinise, but also to dissolve and deconstruct, gender. To enact oneself, as Tyra Lundgren does – as neither man nor woman. To give free vent to female sexuality, like Sigrid Hjertén, in compositions that are both introverted and volatile at the same time. To take on the challenge of formulating a modern critically-thinking subject, as Siri Derkert does in her works. The world trembled. Perhaps Nils Dardel’s dying dandy also contributed to the volatility, to the third space. His alter ego perishes in a beautifully enacted death scene in 1918, after casting a final glance in the looking glass at his refined features. Gathered around him are bland-faced women against a bluish-purple background, while the only man present apart from the dandy plays the part of professional mourner.

Different experiences generate different stories, and the best stories, rather than confirming what we already know, challenge and differentiate our perception of an era or a context. The idea of role play is clarifying when we attempt to identify the essential explosive core of modernity that consists of the play between the sexes. The female roles – the unthreatening hobby artist, or the modernist who competes with her male colleagues, the mother, the mistress, the daughter, the wife. The male roles – modernist or traditionalist, decadent or intellectual, gay or straight, returning heroes from the trenches of the First World War. And all the positions in between. The artist Ninnan Santesson, who went to Paris in the early 1900s, writes about her frustration in a letter home dated 1913: “I have tried discussing politics, religion, women’s suffrage, with our boys, and it was like pouring water on a goose. ‘Politics, artists shouldn’t get involved in politics. Leave that to the bourgeoisie!’ […] Religion: ‘Art is our religion.’ – Art, the way they see it. Women’s suffrage they won’t even go near. ‘Let them have it, since they make such a fuss, in art they will never be our equals anyway.’ Words like that can drive me insane and just about make me go berserk. The blind, blind fools, can’t they see that the women are the ones who will regenerate art.”