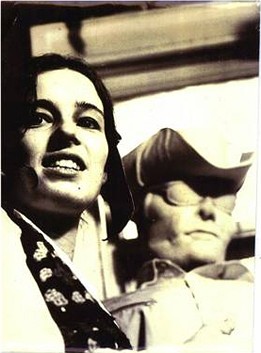

James Rosenquist, I Love You with My Ford, 1961 Foto: Moderna Museet / Prallan Allsten © James Rosenquist /

Bildupphovsrätt 2016

Thematic

The main area of the exhibition, beginning with On, the American Roy Lichtenstein’s painting of a light switch, presents the diverse range of motives and methods shared by art and design. Via iconic sculptures of body parts alluding to Pop Art’s unconcern for individuality, the exhibition concludes with a display of artworks and design objects playing on classic styles, demonstrating Pop Art as an integral part of Postmodernism.

Reality as Collage

The confrontation of contrasting techniques, materials and themes was a typical motif of Pop Art and design in the early stages. It corresponded in aesthetic terms to the upheavals in society and to the subjective reality that was assembled by every individual from the vast array of available media and merchandise.

Image, Object and Sign

As one of the founders of Pop Art, Jasper Johns used flags, maps and targets to draw attention to the phenomenon that things can simultaneously be images, and that images can likewise be things. At this point, designers such as George Nelson or Charles and Ray Eames were already translating functional properties into abstract forms and furnishing rooms with utilitarian objects that doubled as sculptural symbols.

From Folk Art to Pop

Before becoming a celebrated artist, Andy Warhol created a sensation in the 1950s as an advertising designer. He juxtaposed the luxury and elegance of exclusive fashions with naive, playful drawings and kitschy decor. Meanwhile, Alexander Girard enhanced stylish furnishings and interiors with folkloric patterns and traditional handicrafts. Artists as well, including Peter Blake, Judy Chicago and Robert Indiana, adopted motifs from anonymous folk art in their work.

Products in Museums, Art in Department Stores

The Museum of Modern Art is well-known for its post-war exhibitions promoting contemporary design. But as early as 1930, the stage and product designer Friedrich Kiesler had advocated the use of art for merchandise displays in department stores. However, not until Pop Art did the temples of consumerism provide the perfect frame: Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol created their first masterpieces in window displays on New York’s Fifth Avenue.

Thinking Automatons

Electronics, automation and computer technology brought forth a myriad of new appliances and equipment in the post-war period. The variety of such gadgets made life easier and faster, however, an increasingly complex world was evolving in parallel. Even the creation of artificial intelligence seemed imminent.

Quoting Brands

Through advertising, the brand name products of the 1950s became as famous and coveted as film stars. Prominent exponents of Pop Art like Andy Warhol and James Rosenquist had themselves worked as commercial designers before beginning to examine advertising from an artist’s perspective. It is often impossible to determine whether their approach was critical or appreciative. In any case, art contributed to the development of brands as stylistic icons, which were in turn quoted by designers.

Everyday Life Made Public

During the 1950s, the life of the average American became the subject of significant documentary films and photographic series. While the government-sponsored multi-screen presentation Glimpses of the USA glorified the country’s achievements, Robert Frank’s photo series The Americans offered deep insights into the ambivalent soul of its people. One of Frank’s main recurring subject matters was the street: as an anonymous and interminable locale of temptation, and also as a symbol of everyone’s search for happiness.

Bildupphovsrätt 2016

From Font to Image

In conjunction with the growing importance of advertising, the designers of the 1950s became intensely interested in typography. Letters and numbers were consciously designed with the aim of conveying a message. They became symbols for company logos as well as decorative patterns on wallpaper. Pop Art found central motifs in the symbolism of a font and in its effect as an image.

Object, Surface and Trompe L’oeil

Colourful plastics were essential to Pop aesthetics. The structural strength, flexible shapes and variable colours of the new material offered designers the opportunity to concentrate on a product’s appearance. Indeed, many objects seem to consist of a smooth unbroken surface. As hallmarks of the consumer world, store windows, at the edge between inside and outside, provided ideal stages for Pop Art, arousing desire while also creating distance. Artists discovered aesthetic strategies in these attributes, exposing the superficiality of consumer fetishes and culling their subliminal messages.

Drugs and Consumption

While religion was still vilified by communism as ‘opium of the masses’, capitalism was already caught up in the heady delirium of commercial consumption. Yet those who remained unsatisfied by the buying frenzy often turned to real drugs. Cheap cigarettes, in particular, became synonymous with freedom from everyday routines. In works of art, the smoker’s paraphernalia were interpreted as symbols of transience. Somewhat later, the Italian design duo Studio DA saw a motif of ‘enlightenment’ in synthetic drugs.

Artificial Worlds

In the post-war period, the ‘new world’ of America asserted its position as a role model. Everyone strove to establish their own personal world, defined by a house, a television and a car with a radio. A separate, enclosed atmosphere could soon be found in every shape and size, frequently manufactured in the utopian material plastic: from Tupperware, which preserved foodstuffs in airtight containers, to the hermetic dwelling capsule. Even life on the moon seemed within reach.

Everyday Icons

The bold aesthetics of billboards and wall advertisements, which portrayed people and products as stylized icons, was further heightened in Pop Art: the leader of the Chinese Communist Party is depicted as a pop star, or a sewing machine as a household dictator. Designers exploited the motifs and methods of fine art, designing objects in the form of provocative sculptures. A pioneer of this practice was George Nelson, who designed a bedside lamp shaped like an army helmet shortly after the war.

Living Outdoors

In both art and design, the intermingling of work and leisure, of private and public, and of indoors and outdoors emerged as central themes for the post-war Western world. Nature was imitated, fabricated and transformed by artists and designers alike, while families picnicked and the first ever ‘teenage’ generation met and mingled at drive-in movies.

Reproduction and Make-Up

Colours are easily exchanged in the process of printing paper or textiles, and in the production of plastics. These processes permitted a rapid succession of fashion trends and gave mass-produced items an individual touch. Pop Art presented colour as make-up and the product as a copy. Andy Warhol was the first artist to explore this technique strategically creating originals out of copies in a simple, yet brilliant spin.

The Corporeal Object

Artists and designers shared an interest in the playful reversal of inherent properties and natural states, both as a theme and a creative method. Claes Oldenburg’s Soft Sculptures, for example, invested everyday objects with an almost human corporeality by enlarging them and making them pliable. The designer Gunnar Aagaard Andersen allowed the material itself to assume the role of the designer, creating an armchair out of overflowing foamed polyurethane – an object that he regarded as an interpretation of the traditional club chair.

The Dissolution of Images

The intention behind George Nelson’s Marshmallow sofa was to use mass-produced cushions in the manufacture of sofa seating. The grid arrangement of the cushions, however, also transformed the object into a pixel-like image of itself. Works of Pop Art, which literally dissected the aesthetics of duplication, obtained a sort of three-dimensional model with this piece of seating furniture.

Fresh from the Machine

The rise of planned obsolescence in the 1950s increased industrial competitiveness and earnings, while also offering the continual opportunity to improve products and create new styles. Products were mass-produced in countless colours and shapes according to changing trends. One of the first companies to define itself in opposition to this throwaway approach was the electrical appliance manufacturer Braun. The company’s focus on the translation of specific functions into clearly legible symbols made Braun into a model for an entire sector.

Woman as Fetish

The image of women in Pop Art was primarily extracted from the media – predominantly by male artists. Their artworks crop out the advertising context, thereby suggesting that what remains of the female figure is an object of sexual desire, a victim of voyeurism or a doll-like mannequin devoid of personality. In Europe, especially in Italy, designers transformed Pop Art’s female images into sculptural plastic furnishings. Some of the most flagrant fetishist artworks and designs provoked storms of feminist protests.

The Monumental Body

Pop Art was not interested in the individual, but rather in the common masses. It portrayed human beings as machines, as characters in comic strips or as drawn advertising figures, typically without faces or personalities. Only in photographs did people still appear. But by replicating singular body parts with distinctive, unmistakable characteristics, Pop Art alludes to the general loss of personal dignity and integrity.

Post-modern Clichés

Pop Art interpreted the cultural artefacts of bygone eras as prop-like elements that had long since become clichés. It demonstrated that ideals, particularly those of classic Modernism, were no longer timeless. In architecture, which had always been a source of lasting values, a new style emerged as well, one that confronted the historical past with the present: Postmodernism.

The Art of Graphics

Graphic art serves a purpose for printed media as well as for the development of lasting brand images. The task of translating information into visual images that are published and duplicated, allied design with art. Operating on the interface between the fine and applied arts, graphic design gained increasing importance as of the 1950s – as manifested in advertisements, packaging, magazines, posters and album covers.

Living in Pop

It was not long before Pop Art was selling well in galleries. In this way, paintings and sculptures depicting ordinary, everyday life entered the homes of wealthy collectors. For the first book on Pop Art, published in 1964, Ken Heyman photographed private residences in New York that showed scenes of domestic life accompanied by Pop Art. One of the most prominent European collectors was the ‘gentleman-playboy’ Gunther Sachs. In 1970, he showed photographer Ulrich Mack around his penthouse apartment in a Saint Moritz hotel for a feature story in Stern magazine.