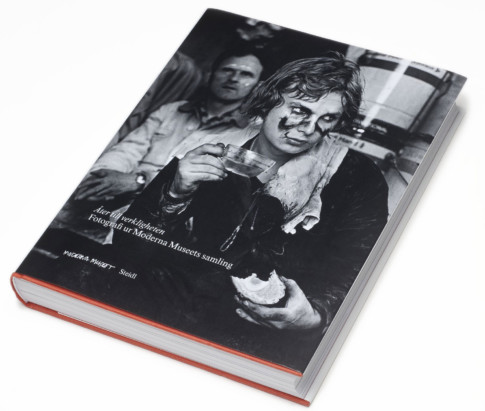

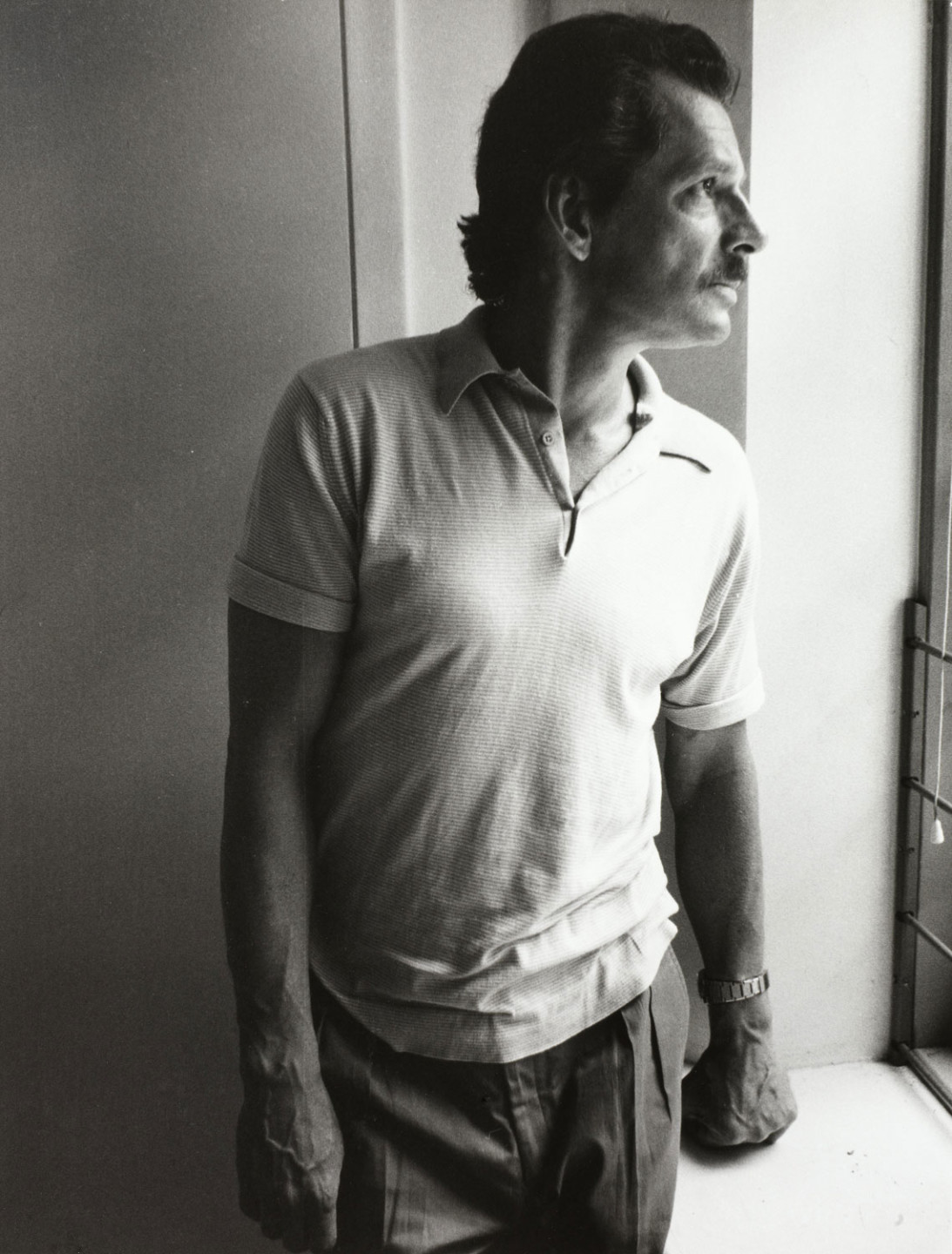

Leif Wigh, Fotografen Bill Owens med familj Livermore Valley, 1975 Reproduction photo: Åsa Lundén/Moderna Museet

When time stands still

“Two flights up,” the voice came from above, through the light shaft in the old industrial building down on West Broadway, New York. I started walking up the cast-iron staircase. After a while I could see the head of someone leaning against the banisters. A head of wild, burly hair. He took my hand, introduced himself – Ralph Gibson. Bright, searching, not to say inquisitive, eyes. Apart from that, he struck me as arrogant, self-conscious and slightly aloof, an impression that has not changed over the years. But under the surface, he turned out to be both warm and generous.

In spring 1975, I was travelling all over the USA, a society that was not in Europe’s good graces. In those days, we did not have the internet or mobiles. I had just returned to New York after a longer stay in New Orleans. I was travelling the USA to meet photographers whose pictures interested me. The photographs created by my own generation in contemporary USA featured human relations and reflections in an entirely different way than those produced in Sweden. One of the photographers I was most keen to see was Ralph Gibson. I had tried to locate him the previous spring but had failed.

In San Francisco I had run into friends of Ralph by sheer coincidence. When they heard I wanted to meet him they grabbed the telephone and called him. So, the meeting had been set up a month earlier. My interest in Ralph was stirred by the photographs published in the British magazine Creative Camera, which led me to one of his books, The Somnambulist. He had founded the publishing company Lustrum Press which published his own works, but also pictures by other photographers who found inspiration in more spiritual depths, including Mary Ellen Mark, Erica & Elizabeth Lennard, Neal Slavin, Robert Frank, Michael Martone and Larry Clark.

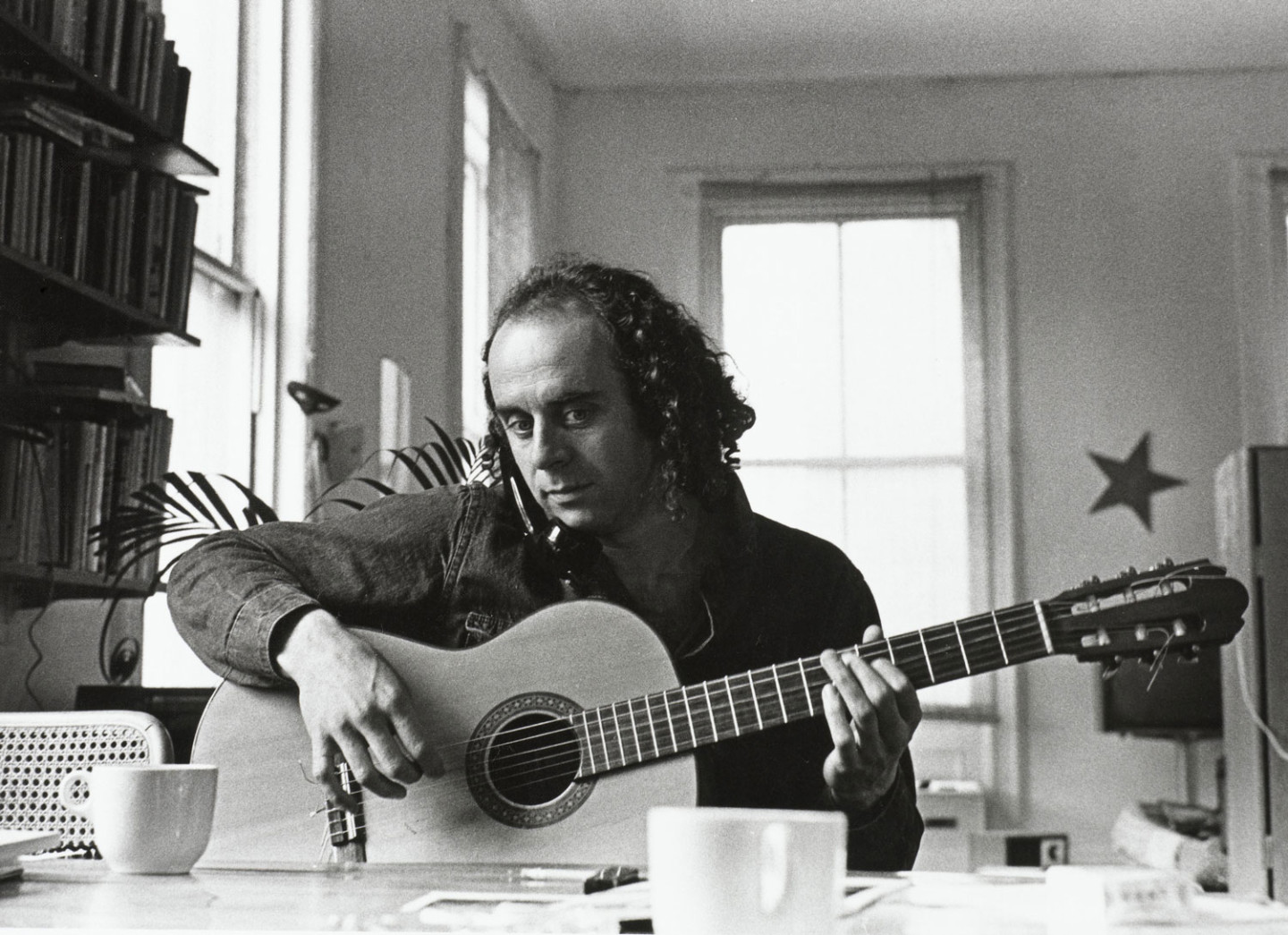

His studio was spacious and the Spartan but sophisticated interior suggested that his business was financially stable. We spoke about Ralph’s relationship to photography as a means of expression, and naturally about his Leica, Tri-Z, Rodinal and Agfa paper No. 5, like others who had grown up with LIFE magazine. He was inspired by both music and literature, especially the authors Richard Brautigan and the circle around Lawrence Ferlinghetti. His photos were often about dreams, sexual fantasies and Freudian relationships. Ralph grew up in Hollywood, where his father had a foot in the film industry, and had periodically led a varied and unorganised life, something that was fairly common for his generation. This also came to expression in his early photos.

He also worked for some time as an assistant to the icon Dorothea Lange, and assisted Robert Frank with a couple of his remarkable, dark and extremely personal films. Robert Frank later let Ralph take over his studio.

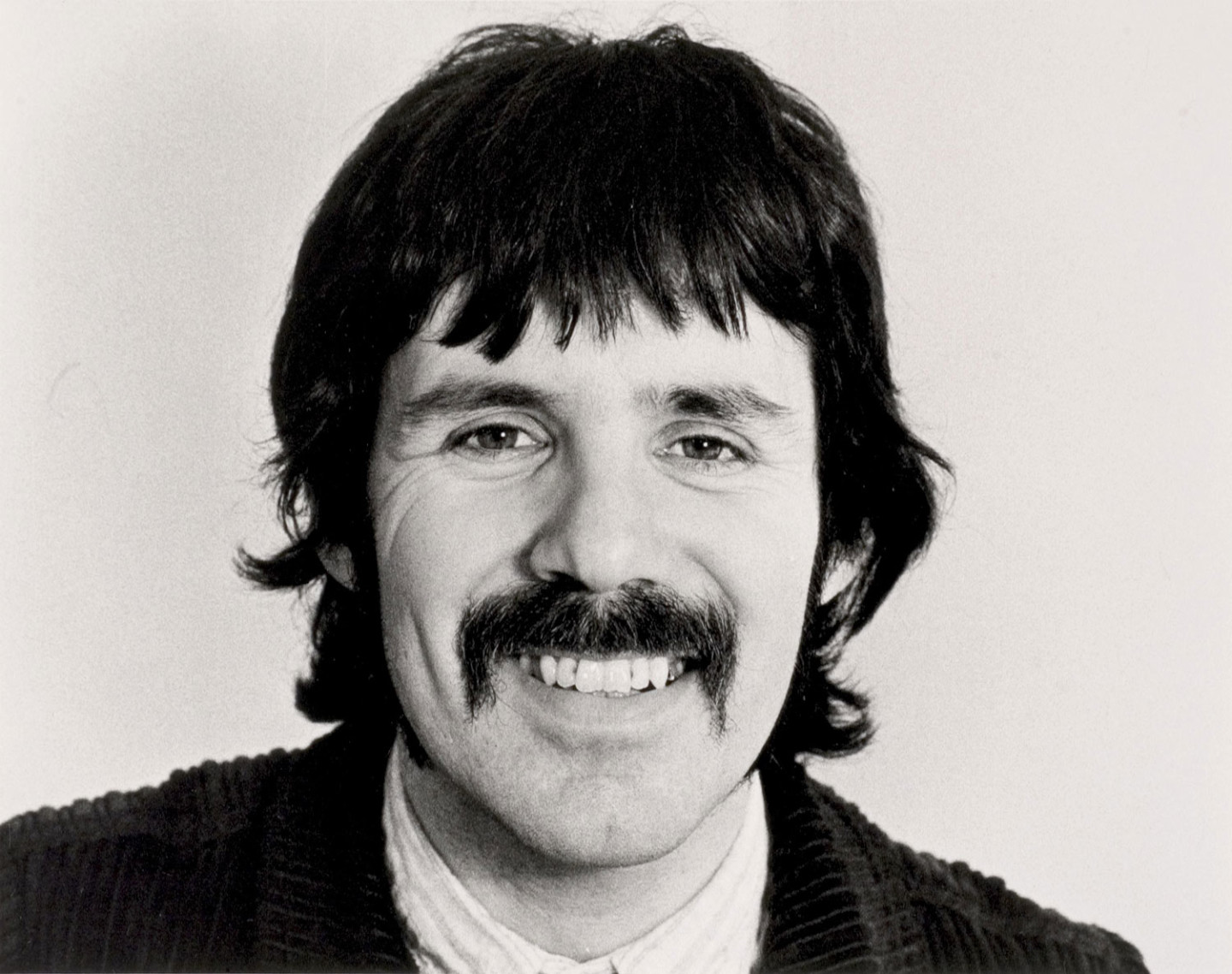

Music forms a significant part of Ralph’s life. He toured with Leonard Cohen as his guitarist and also played on his record New Skin for the Old Ceremony. He also had his own band, Soho’s Own Sex‘n Drug Band, together with a couple of other artists. Morning turned into afternoon, which turned into evening. Since I was interested in the music of Ornette Coleman, Ralph tried to get hold of Coleman, who lived just round the corner. They were old friends. But no luck.

My first meeting with Ralph Gibson, who was like an umbrella for a whole generation of artistic photographers, led to contacts with other visual artists over the ensuing years. But above all, it led to the solo exhibition that opened at Christmas in 1976 in Moderna Museet’s west gallery, which was thus dedicated to photo exhibitions. Moderna Museet now has a large collection of Ralph Gibson’s revolutionary works. Early in the new millennium, Ralph said to me, “You’ve made me a name in Europe.” Whether that is true or not, Gibson’s exhibition at Moderna Museet was undeniably one of the first presentations of his works in Europe.

Bill Owens’ photos had also appeared in Creative Camera, which was perhaps the most seminal channel for the introduction of new photography in Europe in the 1960s and 70s. Owens had become famous throughout the USA for his photos from a Rolling Stones concert in San Francisco. The Stones had made the mistake of hiring Hell’s Angels as security for their concerts on the West Coast. They beat a member of the audience to death in front of Bill Owens and the rest of the people there.

For some years, Bill had been portraying Californian suburbia, which was expanding rapidly and taking over fruitful farmland. He himself lived with his family in such an area. Thanks to excellent social skills, he had formed a large network of friends in the Livermore Valley, a large region packed with prefab houses, inhabited by middle-class Americans with barbecues. Bill Owens’ photo book Suburbia was captivating and expressive. I perceived it as a skilful and astute description of the American Dream usually only found in literature.

During my stay in San Francisco, I looked for Owens. I asked for him in galleries, at openings, but nobody really knew where he was hanging out. On one occasion, I bumped into a man who worked at WAAM – the Western Association of Art Museums. He knew where Owens lived and had previously been in touch with him.

The man, whose name escapes my memory, invited me home to meet his family, and I stayed the night in their new waterbed. They had bought a plot of land and built a house in an old farming district where the land was now being developed. The family led a semi-normal hippie life, and since the job at the WAAM was slightly at risk, they had invested in a few smaller agricultural appliances that the wife was supposed to operate. They had just launched a marketing campaign offering neighbours help with their tomato crops.

Anyway, the man got hold of Bill Owens, who came and collected me after a day or two. At first, Owens didn’t say hello to me – I didn’t exist – but talked only to the contact and his family. After a while, he turned to me and said, “Okay, let’s go!” We drove through the spring-green Californian countryside and eventually arrived at a station house by a disused railway line. A restaurant had opened in the building and Bill invited me to lunch there, among blue-haired ladies who looked worried by my long black tresses. “He’s from Europe,” Bill explained, pointing at me. “We need to talk first,” he said, “to see if there’s any point in this for me!”

Then he phoned his wife from the restaurant and said, in a loud voice, “The guy is okay!” We drove on in his car and eventually came to Livermore Valley and his home. He and his wife had two sons and the house was just like the other houses in the area. “I’m going to take a nap,” said Bill, and left me in the company of his wife who had taken on the self-assigned task of interviewing me while cooking an elaborate dinner. After an hour or so, Bill returned and took me with him to the car again. We drove off to a school a few miles away, where he talked about his photography to a group of teenagers. There was no teacher in sight. Bill spoke for more than an hour, and I suddenly realised that school was over for the day and that the kids had taken voluntarily arranged Bills talk through their teacher.

Back home again, we were treated to a sumptuous meal, washed down with Californian wine. Bill Owens talked about his book Suburbia, saying that it was not a nightmare portrait. On the contrary, the images described a region that he was deeply attached to and was now firmly rooted in. Some of the inhabitants were distant relatives of him and his wife. So in that respect, I had misinterpreted the intentions behind his photos.

It was time for me to return to San Francisco. Bill’s wife thought a bus would be passing a few miles from their home. If we hurried I would make it in time and could then change to a train that would take me to the city. Bill drove me to the discreetly posted bus stop and left me by the side of a road that stretched across a broad plain. On the horizon was a mountain range. “Yosemite,” Bill Owens said, pointing, “There’s a bus,” and he started the car and left me in the middle of the plain. I had ample time in the dusk to study Yosemite at a distance, a name familiar to all photo-lovers since the mountains were a haven for all American landscape photographers, headed by Ansel Adams.

Bill Owens’ photographs eventually won recognition also in Sweden, and a portfolio from “Suburbia” was shown a few years later at Moderna Museet. More photos were added to the portfolio subsequently and the entire series is now in the Moderna Museet collection.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, I tried to get Larry Clark for an exhibition at Fotografiska Museet at Moderna Museet. His photographs in the book Tulsa were both frightening and fascinating. They described a life that was entirely foreign and strange to me. Larry’s name had also cropped up in a musical context. He played the drums on a record with the famous saxophonist Steve Marcus, “strawboss” for many years in Buddy Rich’s big band. Larry managed to unrhythmically demolish the whole record, and it was several times elected as one of the worst jazz records of all time.

Ralph Gibson was an old friend of Larry Clark and had, as mentioned, assisted him in publishing Tulsa. On my visits to New York, I asked Ralph if he could help me get in touch with Larry Clark. But Ralph just shook his head, as always, and explained that Larry was away on a photo project. After several similar attempts, Ralph informed me on one occasion that Larry was back in town. We looked him up and it turned out that he was a fairly young man, approximately our age, albeit more worse for wear. Ralph left us and I told him why I was there. “I’ve been looking for you for years, but you’ve always been out travelling.” “No,” said Larry, “I’ve been in jail and I guess Ralph didn’t want to tell that to a museum curator from Europe.”

Larry had been through hard times but could at least keep himself going thanks to methadone. His book about Tulsa sold many copies and he was just about to publish Teenage Lust, which was to become just as famous. He had invitations from several universities and colleges to hold lectures on his photos and his wild life. Alongside his photography, Larry was involved in a private charity scheme. He was helping young boys to break away from the hard life of the violent gay sex market that was largely centred in Times Square. Larry simply locked the boys in his studio overnight and let them out again in the morning. In the afternoons he rounded them up and gave them something to eat, before going home to his family outside town. He told me that this scheme was not always successful, and that several of the boys had been found dead, floating down the Hudson River or East River on the other side of Manhattan.

After talking about it for a few days, we decided to do an exhibition in Stockholm, and later brought Larry over for the opening. This was one of his first, or perhaps even his very first, exhibition in Europe. An exhibition that was widely acknowledged for its candid contents, as was his lecture in the packed museum Cinema. As we know, Larry Clark later also became known as a film director.

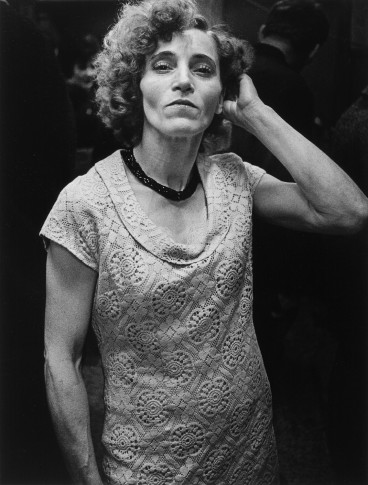

Melissa Shook’s name and photography had cropped up briefly in contexts I now forget. She first awoke my interest with her completely unreserved portrayals of herself in images and diary notes. Melissa had experienced a difficult childhood and lost her mother at an early age. Before that, she had been popular at school and was even elected the school’s Miss World! She was born in a small town somewhere along the Hudson River, but broke up early, took off into the world and eventually ended up in California, where she lived for some time with a man and gave birth to a daughter, Krissy. After a few years, she left California and moved back to the East Coast. At around that time, she also began to explore why her memory of her early teens was completely erased. With the aid of Krissy and her camera, she tried to salvage memories from oblivion and to work out what had happened to her before she reached her teens and puberty.

In the late 1970s, the Swedish-American Birgitta Ralston visited Moderna Museet. Birgitta had modelled for photographers such as Irving Penn, Richard Avedon and Martin Munkackzi, but when she turned 30 and had a family and was living in Boston, she decided to become a photographer herself. On one of her visits we discussed various American phtographers. One of the names that popped up was Melissa Shook. It turned out that Birgitta had met Melissa and could put me in touch with her.

Melissa’s pictures were first shown in the major photo exhibition Tusen och en Bild (A Thousand and One Pictures), curated by Åke Sidvall and myself. A larger collection of Melissas pictures was later included in the show Look Back in Joy, which also featured photos by Birgitta Ralston. Both, along with all the photographers who were still alive, were invited to the exhibition, where they held lectures in the Cinema and attracted great attention for their unique approaches to photography. Melissa Shook is an exceedingly sociable and humanistically oriented individual. For many years, she was employed caring for elderly women who had been left without savings or pensions when their husbands died.

On one of my trips to New York, a few months after the exhibition had closed, I decided to go to Boston and revisit Melissa Shook. It was on that occasion she handed over the complete collection of photographs, meticulously signed, that are now in the Moderna Museet collection of photography.

A few years later, attempts were made in France to launch the concept of The New York School, bunching together these photographers. But the concept disappeared very rapidly, since these photographers approached photography as a means of artistic expression in very different ways.

Text: Leif Wigh (From Friends of Moderna Museet‘s membership magazine Bulletinen no 2, 2009)