Johan Wilhelm Bergström, Self-Portrait, ca 1850 Daguerreotyp

Biographies the first photographers

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851)

Photography had its breakthrough in France, where the theatre and panoramic painter and diorama owner Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre is the man behind the first successful photographic medium, the so-called daguerreotype. A few years earlier, he had begun working with the scientist Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833), who had been experimenting for a long time on how to stabilise images on paper with silver salt. They formed a partnership and tried to develop the process together. When Niépce died, Daguerre continued on his own. He found influential friends who promoted his in-vention.

When the technique was announced on 7 January, 1839 in the French Academy of Sciences, by the physicist and politician Jean Dominique Arago (1786–1853), newspapers wrote about this experiment and the public became interested. Before the end of 1839/40, Daguerre’s handbook had been published in six languages: French, English, German, Spanish, Danish and Swedish.

William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877)

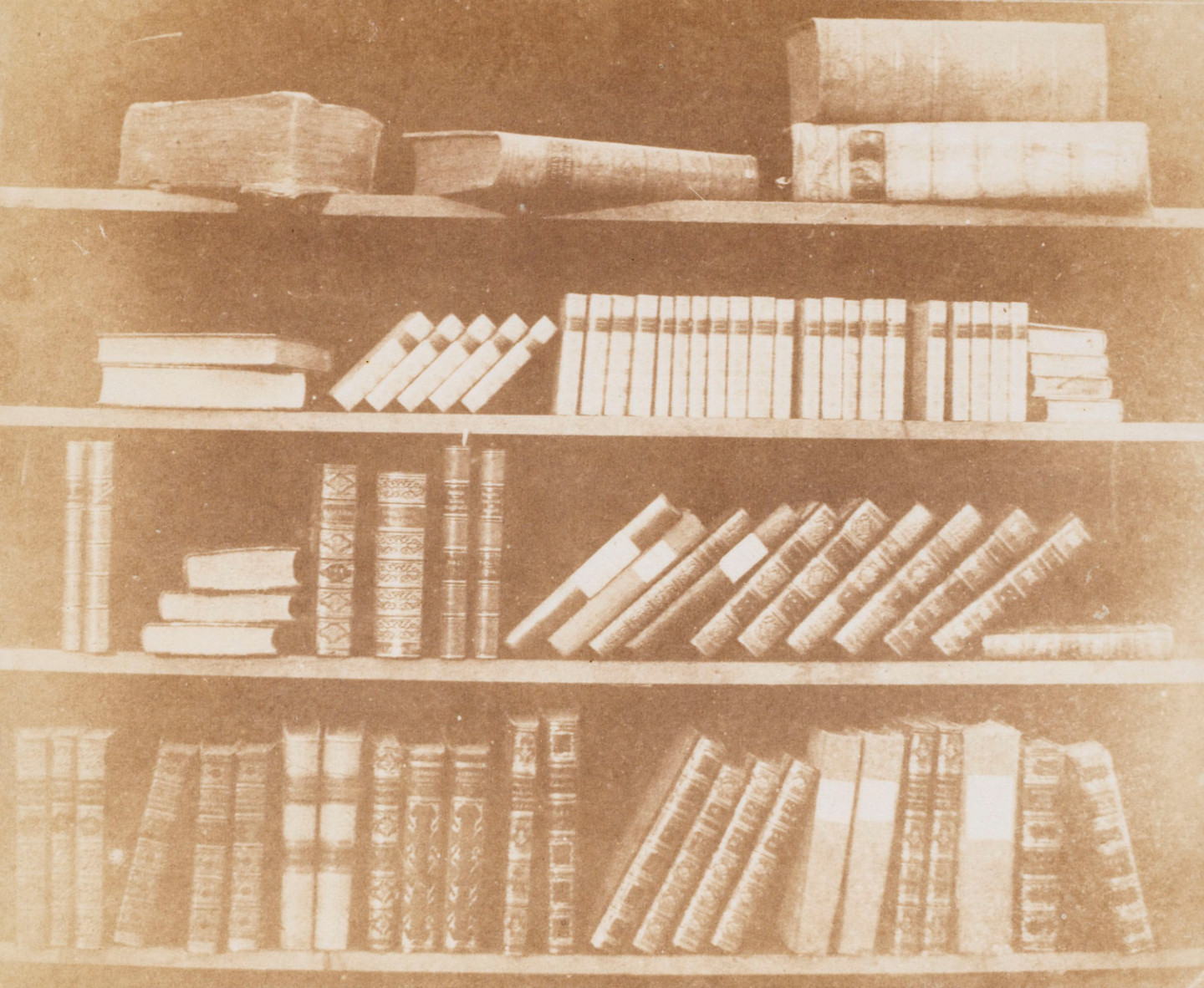

The Scientist William Henry Fox Talbot in Britain experimented with various silver salt solutions on paper. In the mid-1830s, he succeeded in producing a negative image on photosensitive paper in a camera and had thus ingeniously invented the negative.

In 1844–46, he published what could be regarded as the first photographically illustrated magazine, The Pencil of Nature, in which he described the technique and how photography could be used in prac-tice. He himself claimed that its most important use was to produce evidence, but he also had artistic ambitions for his photographic images. It was Talbot who eventually launched the term “photography” (writing with light) for his invention. Many different words and metaphors were used to describe this new medium, but photography was soon established as its proper name.

Robert Adamson (1821–1848) and David Octavius Hill (1802–1870)

The first prominent calotype practitioners were active in Scotland, which was exempt from Talbot’s patent restrictions. David Octavius Hill was a portrait painter, and Robert Adamson an engineer. In 1843, they began collaborating as photographers, after Hill had been assigned to portray a group of clergymen and laymen who had left the Church of Scotland and founded the Free Church of Scotland. Hill wanted to use photographs to create individual portraits of the several hundred participants in this assembly.

It took them more than a year to produce a calotype of each member, and the painting took another 20 years for Hill to complete. They continued working together for four years, until Adamson’s premature death, producing nearly 3,000 photographs of architecture, landscapes, but especially portraits, which they always signed together. They also documented working women and men in the fishing village of Newhaven near Edinburgh in a natural and personal style that was unusual for that period.

Oscar Gustave Rejlander (1813–1875)

One of few internationally famous Swedish photographers is Oscar Gustave Rejlander, but little is known of his early life in Sweden. He settled in Britain around 1840, where he worked as a photographer until he died. He had probably studied art and was interested in art history. His works show distinct influences from Italian renaissance, Spanish baroque, Dutch 17th-century painting and the British Pre-Raphaelites.

In his studio, he would build and photograph a kind of “tableaux vivants”, or staged scenes. Perhaps the most famous of Rejlander’s works is The Two Ways of Life from 1857, a negative montage consisting of some 30 exposures combined into a composition. Rejlander’s oeuvre also includes a series of pictures of poor children and families. Towards the end of his life, Rejlander met Charles Darwin and was commissioned to illustrate his acclaimed book The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872).

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879)

In Victorian Britain, a small group of photographers were the very first to attempt to create and formulate art photography. Julia Margaret Cameron, who belonged to this group, left behind a fantastic collection of intimate portraits of her family and large circle of friends. She was an amateur photographer who was active mainly in the 1860s and 1870s.

Her staged pictures, inspired by myths, biblical stories and English literature, have a characteristically expressive soft focus. Cameron’s photographs are reminiscent of the Pre-Raphaelites and renaissance painting. The Moderna Museet collection of Julia Margaret Cameron includes portraits of Charles Darwin, Henry Taylor and Alfred Tennyson, along with staged tableaux of The Angel at the Grave and the melodramatic Maud from one of Tennyson’s most famous poems. Cameron’s last major photographic project in the UK, before she and her family moved to Ceylon, present Sri Lanka, was to illustrate Tennyson’s work Idylls of the King (1874–75).

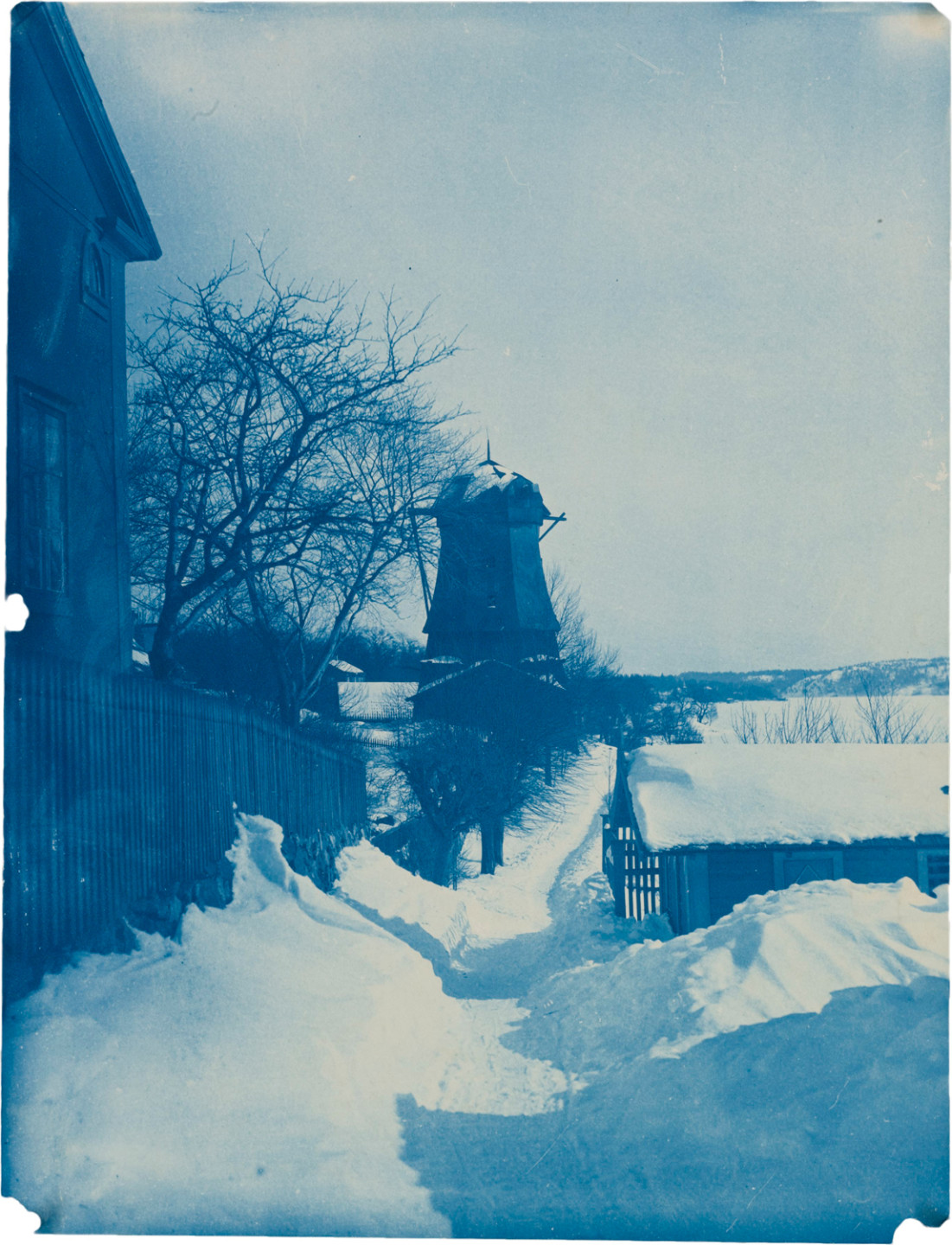

Carl Jacob Malmberg (1824–1895)

The collection Carl Jacob Malmberg left behind includes most photographic techniques and image types. He is also an example of a photographer’s career development after the first innovative period in the 1840s and up to the 1890s. Malmberg was born in Finland and first studied to be a goldsmith in St Petersburg, where he also learned photography.

He moved to Stockholm, where he opened a studio in 1859 on Drottninggatan 42, and later on Norrtullsgatan 2, and finally on Regeringsgatan 6. Around this period, when cartes-de-visite portraits came into fashion, Malmberg’s practice really took off. On a visit to Finland in 1872, he took a series of pho-tographs at Fiskars iron mill, documenting all the workshops and buildings. A slightly odd portfolio in Malmberg’s collection consists of more than 100 pictures of gymnasts. He had been commissioned by Hjalmar Ling at the Gymnastiska Centralinstitutet in Stockholm to take these pictures to illustrate the book Förkortad Öfversikt af allmän Rörelselära (Short Summary of General Exercise Physiology, 1880).

Carleton E. Watkins (1829–1916)

Voyages of discovery, nature and landscapes were popular motifs for the early photographers. The growing tourism increased demand for pictures from exotic places, making this a source of income for publishers of photographic literature. The American West was one such region, and some of the photographers who began working there also documented the American Civil War. One of the most prominent of these was Carleton E. Watkins, who had travelled and photographed the Yosemite Valley on several occasions in the first half of the 1860s.

In his large-format photographs, so-called mammoth prints, he captured the massive mountain formations, dramatic waterfalls and gigantic trees. His heavy equipment was carried by some ten mules, and it is almost a miracle, considering the difficult conditions, that so many of his photographs survived.

A definite advancement in the process of creating negatives was made by the Brit Frederick Scott Archers (1813–1857), who discovered how to use glass sheets for the negative instead of paper. Collodion was used to bind the necessary silver salt to the glass, but it could only be exposed while wet, hence the term wet plate process. The glass negatives gave sharp details, and a large number of paper prints could be made from one negative.

Carl Curman (1833–1913)

The physician Carl Curman had many interests, and studied both medicine and art as a young man. Eventually, he became a famous balneologist, and initiated the plan for public baths in Stockholm and eventually also the Sturebadet swimming baths.

He built a photographic studio at the Karolinska Institute in the early 1860s, and was a pioneer of medical photography, before being appointed a professor of plastic anatomy at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1869. His lectures have been documented, in pictures showing students gathered around Curman for dissections. These photographic studies of the human anatomy were also used in the emerging field of eugenics – a troubling part of Western history.

Curman was never a professional photographer, but is one of the many practitioners who have made their mark on the history of photography. His more private projects include pictures from Lysekil, where he worked as a balneologist, from Stockholm where he lived, and from various travels abroad, together with his wife Calla Curman, co-founder of the women’s society Nya Idun.

Rosalie Sjöman (1833–1919)

Rosalie Sjöman was one of many prominent women photographers. She opened a studio in 1864 on Drott-ninggatan 42 in Stockholm, after being widowed with three small children. The photographer Carl Jacob Malmberg had had his studio at this address previously, and there are some indications that Sjöman may have been working for him. Her business prospered, and towards the end of the 1870s Rosalie Sjöman had five female employees, and she seems to have chosen to hire women only. R. Sjöman & Comp. later opened studios on Regeringsgatan 6, and in Kalmar, Halmstad and Vaxholm.

Her oeuvre includes numerous carte-de-visite portraits and larger so-called cabinet cards, with a mixture of classic portraits, various staged scenes, people wear-ing local folk costumes, and mosaics. The expertly hand-tinted photographs are especially eye-catching; several of them portray her daughter Alma Sjöman.

In the 1860s, photography progressed from being an exclusive novelty into a more widespread and popular medium. The popular carte-de-visite were introduced in France in the mid-1850s, but became extremely fashionable when Emperor Napoleon III had his portrait made in the new format (6 x 9 cm). This trend spread rapidly, and portrait studios opened in large cities and smaller towns. This cartomania lasted for a decade, and the market stabilised around the mid-1870s, when the photographic med-ium entered a calmer phase.

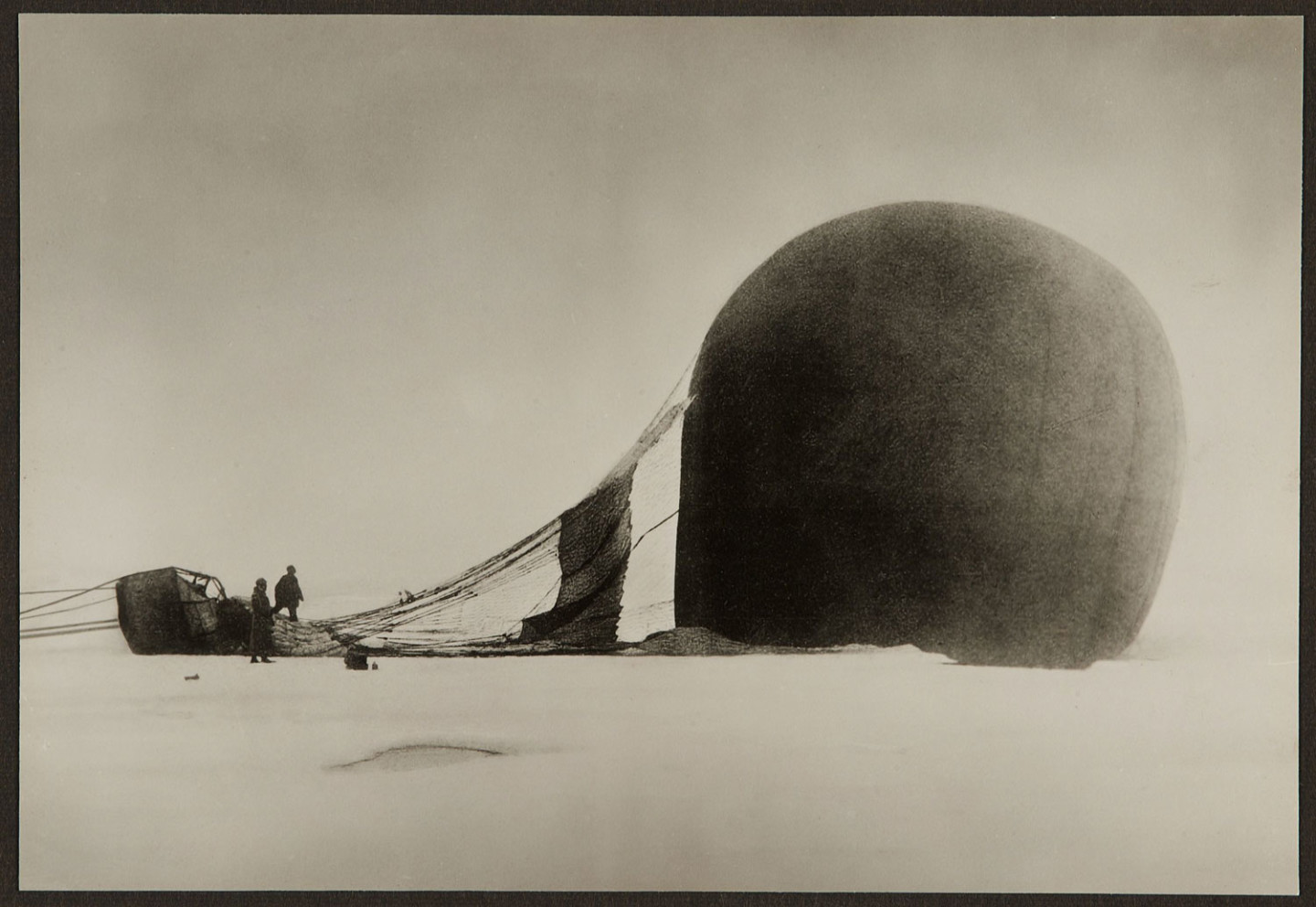

Nils Strindberg (1872–1897)

In July 1897, Salomon August Andrée (1854–1897) embarked on his voyage to the North Pole in the balloon Örnen [The Eagle], accompanied by the engineer Knut Frænkel (1870–1897) and the photographer Nils Strindberg. A few days later, the balloon crashed on the ice, and they were forced to continue their journey on foot. The conditions were severe, and the ex-pedition ended in disaster. After a few months, in October, they made up camp on Kvitøya on Svalbard. This is where their bodies were found thirty years later, along with Strindberg’s cam-era.

The expedition and the events surrounding it, were widely publicised both at the time of the expedition, and later when they were found. Per Olof Sundman’s book The Flight of the Eagle (1967) was turned into a film by Jan Troell in 1982. Although these photographs were taken as scientific observations, and to document the work of the members of the expedition, they now appear as some of the most remarkable and beautiful photographs in polar history.

John Hertzberg (1871–1935) was a photographer and docent at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology. He was commissioned to develop the exposed films, and managed successfully to process ninety-three of Strindberg’s photographs. He made copies of the negatives, which were used to produce the prints on paper that are now at institutions including Moderna Museet, the National Museum of Science and Technology in Stockholm and Grenna Museum – Polarcenter in Gränna.

The original negatives ended up at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm. Hertzberg re-touched some of the pictures, and these are primarily the ones that have been published and embody the public perception of the expedition. Moderna Museet has both sets, and the retouched photographs are shown above the unretouched versions in this exhibition.