Edi Hila, Street Scene, From the series Threat, 2005 Courtesy Brian McCarthy & Daniel

Sager, NYC

Edi Hila – At the Rupture Between World Orders

In 1991, one of the world’s most closed and repressive regimes – Albania’s communist dictatorship – falls. Until this point, the Stalinist government has denied Albanians passports, and any attempt to flee the country has been punishable by death. Political alliances with the outside world have long been severed – first with the Soviet Union (1961) and then with China (1978). When the last dictatorship in Europe finally collapses, the Albanian people have lived in isolation for more than four decades.

Many now attempt to leave the country. Images of overloaded boats carrying thousands of migrants – desperately trying to reach the shores of Italy – circulate in the international press. Edi Hila, who decides to stay for family reasons, emerges as an artistic witness to this profound political upheaval. With a sharp eye, he observes and documents how the dramatic transition to a capitalist society affects the people around him and their shared environment. The small Mediterranean country is expected to undergo a rapid shift towards democracy and a market economy. This brutal transformation not only leads to a reassessment of values and relationships but also profoundly impacts the built environment and the natural landscape.

Through his paintings and acute observations, Edi Hila immortalizes this pivotal era in Albanian history. From the late 1990s onwards, he depicts how Albania’s transformation manifests both in the human soul and in the surrounding landscape. He traces the explosive creativity and ingenuity that suddenly find space to flourish in the gaps and grey zones between two regimes. At the same time, he portrays how corruption and organized crime infiltrate society and undermine already fragile social structures.

Edi Hila’s visual world is deeply rooted in physical reality while simultaneously revealing the invisible and elusive. Menacing atmospheres and charged moods become perceptible, and with striking precision, he captures the unsettling sensation of losing one’s footing entirely.

We believed in a quick transition to democracy, but it didn’t happen that way at all. /Edi Hila, 2018

The darkest year

The transition from an authoritarian one-party state of the Stalinist variety to a democratic multi-party system proves both difficult and painful, much like the shift from a socialist planned economy to a capitalist market economy. Six years after the fall of the dictatorship, in the spring of 1997, post-communist Albania teeters on the brink of collapse, and violence prevails.

Amidst this difficult and chaotic time, Edi Hila creates his monumental and deeply moving triptych, “People of the Future”. In the first and third paintings, a ship looms against a darkening blue sky, positioned close to the picture plane. Its powerful searchlight pierces through the twilight, projecting a white circle – reminiscent of a menacing, all-seeing eye. Up on deck, a dense black mass of people emerges – restless, pressed together, their forms and faces unreadable. In the chaos, some appear to have been pushed over the railing, plunging into the merciless waters below.

The event that inspired the triptych is described by a then 17-year-old Lea Ypi – now a writer and professor of political theory – in a diary entry from 29 March 1997:

“A boat sailing from Vlora to Italy sank last night near Otranto. It carried around one hundred people and was hit by an Italian military vessel which was patrolling the waters. The Italians made a manoeuvre to try and stop the boat and it capsized. There are around eighty bodies disappeared at sea, they’re still searching, mostly women and children, some as young as three months old. Our prime minister had signed an agreement with Prodi the day before, he agreed to the use of force to ensure Italian control of territorial waters, including hitting vessels at sea as a way of sending them back. I’m not taking Valium anymore, I’m taking Valerian, it’s meant to be milder.”

The triptych “People of the Future” serves as a lamentation on the tragedy of Otranto and countless other similar events. In the artwork, fear, anxiety, and military ruthlessness intertwine in a gripping visual presence. Through the painting’s dense atmosphere, the muffled signals of the ship’s foghorns seem to rise, punctuated by the relentless roar of the greyblack waves crashing against the hull – like snarling wolves stalking their prey.

At this time, in the spring of 1997, Albania is in a state of collapse. The government has lost control of the country’s southern regions, many in the police and military have deserted, and a million weapons have been looted from their arsenals. A close friend who lived through this period described it as if the population – in complete desperation and despair – had succumbed to a kind of collective self-destructive frenzy.

The trigger behind this dark chain of events was the collapse of a number of investment funds – pyramid schemes – that had been established in the country some years earlier. Lured by promises of sky-high interest rates, scores of Albanians were persuaded to invest all their assets. The absence of a functioning banking system and the fact that the government had publicly endorsed these companies, led Europe’s poorest people to sell their homes and land, investing their life savings.

When these financial illusions finally crumbled, many were left completely destitute. A wave of violent unrest broke out, and while foreign citizens were evacuated, thousands of desperate Albanians attempted to flee the country by any means possible.

In other paintings from this fateful year, Edi Hila revisits the experience of living in a world on the brink of collapse – a sensation of walls and floors giving way, everything dissolving into a chaotic void. In his series “Comfort” (1997), a sparsely drawn figure sits upright, its legs stiffly extended on a black sofa. The same sofa reappears in another painting, where only faint traces of human presence remain – on the verge of complete dissolution. Murky grey water does not merely surround the subjects in these paintings; it seems to seep into them, eroding their forms into something unrecognizable and indefinable. In stark contrast to the alluring promises of a better life – with luxury, comforts, and hope for the future – these works evoke a profound sense of anxiety, of losing oneself in a soulless no-man’s-land.

A Time of Paradoxes

After the chaos of 1997 came a period of increased stability, and among the paintings depicting the dawn of the new millennium, one can even discern a dash of humour. The humorous undertone, though subdued, arises from Edi Hila’s keen sensitivity to the many absurd and contradictory situations that, in various ways, expose the complexity of the transitional years. In his paintings, he highlights these subtly comic elements through a melancholic grey palette, as if to simultaneously convey the precariousness of life and the gravity of the moment.

It is during this time that Hila’s “paradoxical realism” takes form – a realism through which the artist conveys many of the unreasonable and absurd aspects of this rapid social transformation. We see it emerge in the painting “Under the Hot Sun” (2005), where bathers gather under parasols on the beach of a coastal Albanian town. Wedged between the ruins of Enver Hoxha’s bunkers in the foreground and a stranded cargo ship in the background, they form a paradoxical fusion of a relaxed holiday atmosphere and the remnants of a violent history.

Freed from the propaganda straitjacket of the communist regime, Edi Hila set out to depict society and its people on his own terms. His realism captures an era shaped by ideological contradictions, parallel economic systems, and people’s tentative efforts to navigate an unfamiliar world. Deeply rooted in physical reality, his paintings are based on photographic references – snapshots from urban wanderings and journeys through the countryside. Yet it is his ability to render the invisible – emotions, atmospheres, and relationships – that gives his paintings their unique strength.

In “Monument” (2005), we encounter yet another example of Edi Hila’s paradoxical realism. The painting captures how a textile merchant in Shkoder has completely taken over a public space, even integrating an existing monument into his business. Isa Boletini (1864–1916), a key figure in Albania’s struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire, has here been reduced to a mere fixture of the street commerce – an unintended billboard for the entrepreneurial spirit of a new era. A similar absurdity unfolds in “On the Street – Aquarium” (2007). Here, a glass tank – brimming with live fish – sits incongruously on a sidewalk, as an improvised fish stall amid the dust and concrete of the urban landscape.

These paradoxical elements reveal a dysfunctional society but also highlight the creativity that is born out of chaos. Albania’s transitional years were infused with energy and drive, partly fuelled by the absence of rules and routines. Individuals were forced to improvise and devise their own immediate solutions. Poverty and hardship were undoubtedly driving forces, and it is important not to romanticize this reality. At the same time, people’s resourcefulness and ingenuity flourished – often with comical and, at times, astonishing results.

In other paintings from the period, Edi Hila explores the violence that constantly lurks beneath the surface – like an invisible knife’s edge, poised to cut through the calm of everyday life at any moment. In “Wedding” (2006), a SUV has been decorated to transport newlyweds, yet the scene conveys neither anticipation nor joy. Instead, it vibrates with the tension of latent animosity. Criminal elements have embedded themselves within society, expanding their influence and capacity for violence. And yet, they too fall in love, get married, and seek to celebrate life. In “Threatening” (2008), a group of cars has suddenly pulled over at the roadside, perhaps on the brink of a confrontation. Here too, the scene is steeped in an ominous tension, as if foreshadowing an inevitable act of violence.

The absence of established regulations and strong governmental institutions allowed corruption and organized crime to flourish, eroding the population’s sense of security while simultaneously reshaping the architectural landscape. Chaotic construction sites and abandoned structures stood as stark manifestations of this brutal and unbridled transformation. In his series Transitional Landscapes, Edi Hila captures this reality. He depicts buildings eerily severed from their surroundings, emerging as uncanny portraits of their owners. These structures assert themselves in the landscape, making it clear how the focus has now shifted from collective societal ambitions to individual aspirations.

In several cases the owners of these buildings were also their architects, and the houses often appear crudely dominant and oversized. A series of green paintings, however, set themselves apart with their depiction of considerably more modest buildings. “House on Green Background 1” (2005) is an example of these small white constructions that look like they are about to be engulfed by nature’s resurgence. Abandoned to their fate, they emerge through the intensely lush vegetation – like ghostly monuments to dreams that, for various reasons, were never realized.

Edi Hila himself has commented on these paintings with the following words:

“We’re living through a process of transformation that involves everybody and forces us to make important decisions that can change the course of our life. In these abandoned houses, hope and the desire to inhabit them has departed with the migrant. These houses have been transformed into objects, almost weird and absurd, born of an immediate necessity.”

In “House Surrounded by Wall” (2000), yet another abandoned house – or rather, the skeletal remains of a multi-storey building under construction – stands in the middle of nowhere. The deserted structure has been enclosed by a fence, barring trespassers from entry. Scenes like this were common during the first decade of the new millennium. Large sums of money, often originating from dubious or criminal networks, were funnelled into the construction industry as a means of laundering illicit income. The reasons why many buildings were left unfinished varied: the owner may have left the country, run out of money, been sentenced to prison, or become embroiled in legal disputes over land and building permits.

Gezim Qendro (1957–2018), the late art historian and former director of the National Gallery in Tirana, has described the architectural development in Albania’s transitional period as a “collective and spontaneous invasion of public space”. He argued that Edi Hila, in a singular way, managed to capture the violent nature of this transformation:

“Although the attitude towards the subject is apparently detached and neutral, we feel that there is something strange going on in these empty, gloomy landscapes, forcing us to scrutinize them in order to understand this unease, this disturbing presence of something we cannot see.”

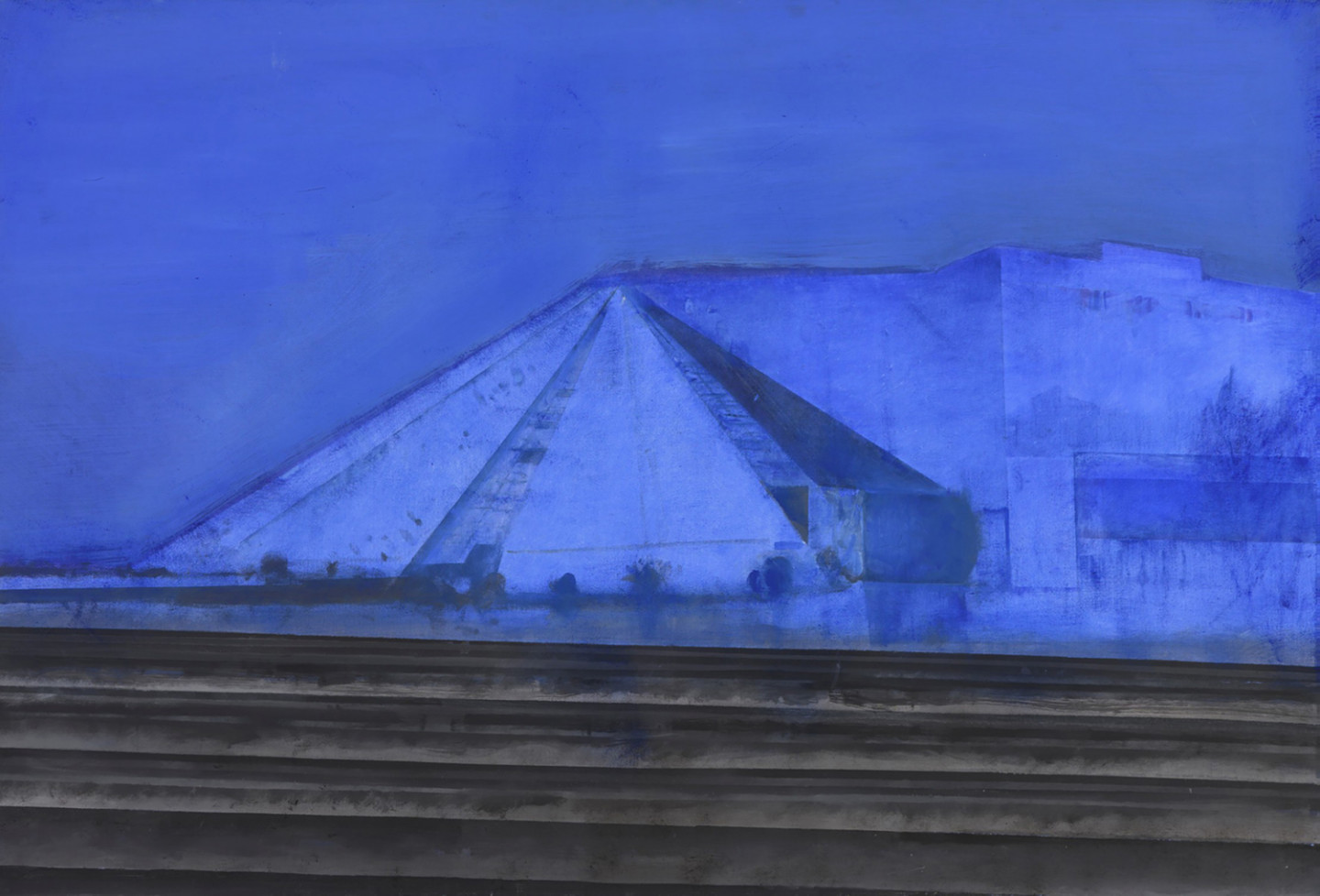

The Pyramid

When I first visited Albania in 1999, it was to organize the participation of three Swedish artists in an international contemporary art exhibition. Part of the exhibition was to be held in the Pyramid, which, along with other historically significant buildings, is situated along Tirana’s most prominent avenue: Bulevardi Dëshmorët e Kombit.

My hosts informed me that the Pyramid had been designed by Enver Hoxha’s daughter Pranvera Hoxha, along with her husband and a team of architects. When completed in 1988 as a museum dedicated to the dictator, the building stood in stark contrast to the surrounding structures, which were primarily built in the Italian Fascist Neoclassical style. Its grand entrance hall was intended to house a monumental statue of the seated dictator, and when viewed from above, the structure resembled an abstracted double-headed eagle – Albania’s national symbol.

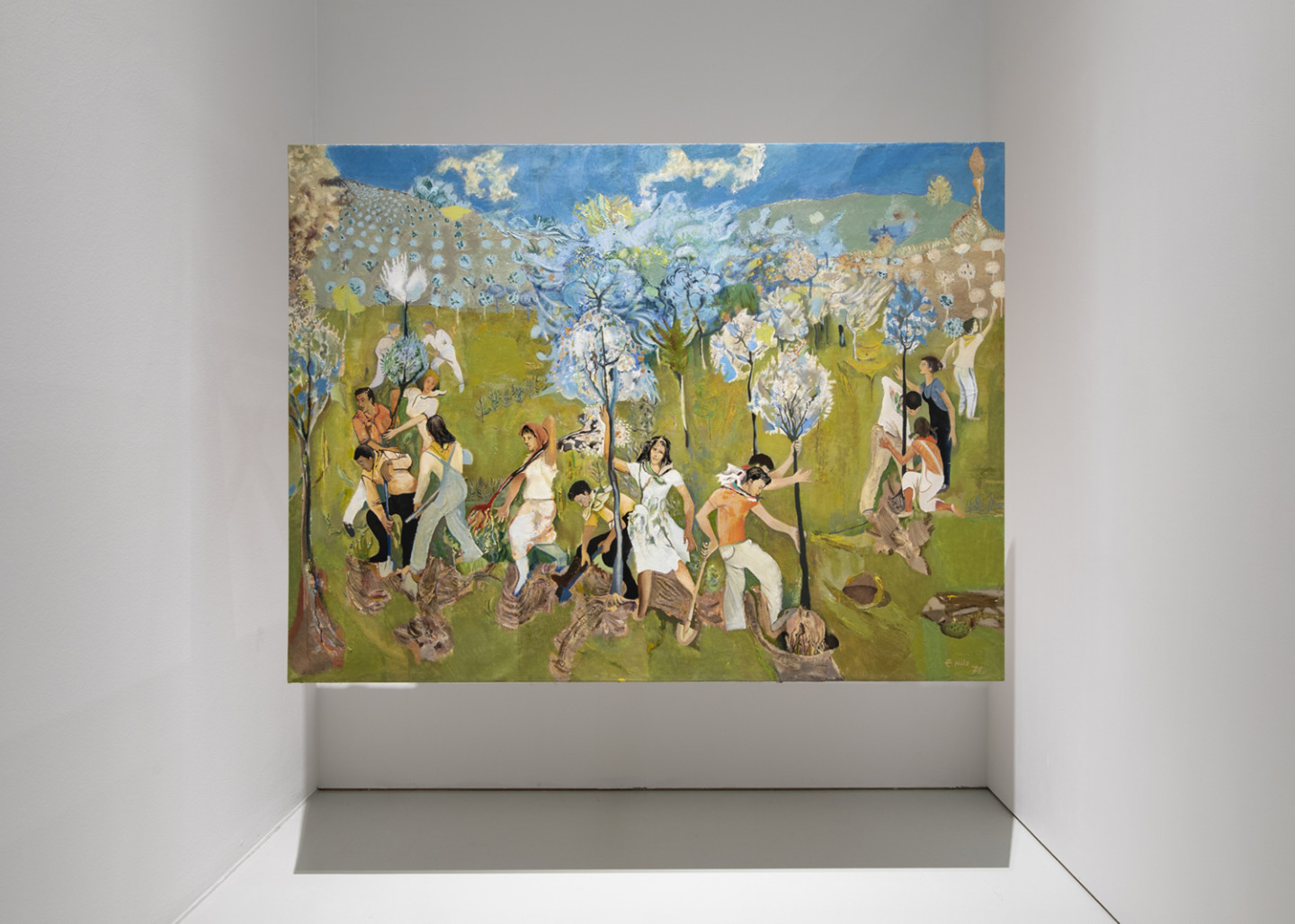

What I didn’t know during my visit in 1999 was that Edi Hila, who, incidentally, also participated in the exhibition, had played a role in designing the museum’s interior. In the early 1970s, Hila was banned from working as an artist and forcibly assigned to a poultry farm, where he spent several years loading sacks of flour. Officially, this was punishment for deviating from the aesthetic doctrines of Socialist Realism – a transgression that, at worst, could put one’s life at risk. Hila’s “offence”, however, was relatively mild; the painting in question, “Planting of Trees” (1971), depicts, after all, a collectivist paradise of non-commercial solidarity. Yet even the slightest “misstep” could be exploited to silence artists and other cultural figures – something the regime actively pursued during this period.

After enduring this prolonged “reeducation” process, Hila was transferred to the “Ornamentation and Decoration Unit” in Tirana. There, his artistic skills were repurposed to produce visual propaganda for the Party, including posters, banners, and public decorations. According to Hila, this was intended as a form of “political rehabilitation” – a continuation of his forced labour at the poultry farm.

Something the Party had certainly not intended – but which nonetheless occurred – was that during those years, while working in the service of socialist propaganda, Hila began to reflect more deeply on the concept of realism, both as an idea and an aesthetic. Burgeoning thoughts on what could define a free and personal approach to realism now laid the foundation for the paradoxical realism that would later come to characterize his artistic practice.

In 2011, more than two decades after the Pyramid was inaugurated as a museum dedicated to Enver Hoxha, Edi Hila returns to this politically charged building. He depicts it from a distance and at an angle, as if to reflect a detached and apprehensive stance. Using a monochrome blue palette, he conjures a subdued, melancholic atmosphere, making the structure appear as if it were submerged in pigmented water. Gone is the defiant, forward-looking symbol of the Socialist Republic’s proud history and progress. Instead, the Pyramid’s identity appears dormant, as though it has been deactivated.

Hila’s melancholic interpretation of the Pyramid reflects its actual fate during this period. After the fall of the communist regime, the museum was vacated and, in 1991, repurposed as the International Centre of Culture. Later, the building was abandoned and left to deteriorate. By the time Hila paints Pyramides, discussions about its demolition are already in full swing. The government’s proposal to replace this communist relic with a new parliamentary building is, however, primarily an attempt to divert the Albanian people’s attention from other, more pressing societal issues.

The year 2011 was a turbulent year in Albania, marked by widespread public frustration and heightened tensions between the ruling party and the opposition. Numerous protests were organized against electoral fraud and rampant corruption, one of which turned deadly. On 21 January, four people were shot and killed by the military during a demonstration in Tirana.

In other works from 2011, Edi Hila revisits the corrosive political discourse and fraught societal climate. In the painting Parliament, the imposing interior of the Albanian Parliament – its floors, ceilings, walls, and furniture – appears to have been sprayed with a stinging, fuchsia-purple pigment. Even the air seems saturated with the same caustic hue.

When viewed together, these paintings from 2011 expose a dysfunctional political landscape and the firm grip of corruption, both within and beyond the state apparatus. The monochrome colour may symbolize the toxic nature of the political debate while also capturing the growing sense of resignation spreading throughout society.

The Penthouses of the Nouveau Riche

In still-unstable Albania, a small group of people has suddenly become immensely wealthy. This newly affluent social class – the nouveau riche – not only reshapes the social fabric of Albanian society but also transforms the very silhouette of the country’s capital.

To assert their status, it has become fashionable within these circles to construct homes on top of existing high-rise buildings. The added floors are often deliberately designed to stand out from the rest of the building. Palatial extensions, dense rows of cypress trees, grand glass facades—or even an opulent Nordic-style chalet – are just some of the architectural extravagances adorning these lofty retreats.

In the series “Penthouse”, Edi Hila captures this urban trend. He depicts towering colossi isolated from their surroundings and set against a vast, empty sky. Though anchored in reality, these surreal architectural fantasies rise like monuments to a new kind of individual – defined by an extravagant lifestyle and an indulgence in personal luxury.

Both in reality and in Hila’s surreal interpretation, these penthouses manifest power and prestige while asserting a deliberate distance from the congestion and grime of street life. By stripping the lower floors of windows and doors, the artist further reduces the original buildings to mere pedestals – elevating these crown jewels of architectural excess.

Despite the series’ contemporary theme, it becomes apparent in “Penthouse” how Hila’s oeuvre is deeply rooted in the aesthetics of the Italian Renaissance. Soft hues of light blue, pink, and gold gently blend with the concrete’s muted grey. As viewers, we are transported through scorching air and dust-laden streets, yet the stillness and poetic palette simultaneously anchor us in an art historical tradition that harks back centuries.

In 1973, Edi Hila had the opportunity to travel to Florence—just a year before he would be sentenced to forced labour. In this bastion of Italian culture, he immersed himself in the masterpieces of Masaccio, Paolo Uccello, Luca Signorelli, Fra Angelico, and many others. Since then, the classical visual language has continued to resonate in Hila’s work, providing a vital foundation that grounds his reality-based social narratives in a poetic realm – one that transcends time and space.

One of the most striking examples of Hila’s connection to this stylistic tradition is “Penthouse 4”. The work transports us to the fourteenth century and to Giotto di Bondone – often regarded as the founding figure of Renaissance painting. The fortress-like structure, silhouetted against a deep cornflower-blue sky, could have been drawn from a biblical scene painted for a church in the Proto-Renaissance period.

At the same time, the facade hints at yet another important historical reference: the Albanian tower houses, or kullë. In northern Albania in particular, the construction of a certain kind of tower-like dwelling proliferated between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries. These structures were often tall and narrow, built like towers with thick stone walls and with windows restricted to the upper floors for protection against attacks.

In an interview, Edi Hila explains that with “Penthouse”, he sought to highlight how the architectural preferences of the new social class reflect isolationist tendencies – and how these tendencies can be seen as historically rooted in the region:

“Building on the top of existing houses, far away from street level, can be read as an expression of fear from others. In this sense, it is a new dimension of the same defensive architecture which we know from the Albanian mountains. In the phenomenon of penthouses, one can also see metaphors that potentially describe a broader psychology of the region in which there have always been local and internal fights and conflicts. These paintings can point toward tensions related to racism, class conflict and much more.”

Martyrs of the Nation Boulevard

In 2015, Edi Hila returns to the buildings along Bulevardi Dëshmorët e Kombit (Boulevard of the Martyrs of the Nation). In a series of six paintings, he explores this grand avenue of Tirana and its surrounding architectural complexes as a cohesive whole – a space shaped by totalitarian ideologies, serving both as a backdrop and a stage for conflicting struggles for freedom.

Public buildings dominate three of the paintings. Designed by the architect Gherardo Bosio during the Italian occupation of Albania (1939–43), their facades bear the fascist, strictly rationalist aesthetic. Both in reality and in the paintings, these structures appear eerily sealed off and mute – as if they were guarding something hidden, unyielding. Their fortified presence in the urban landscape evokes a diffuse feeling that they are harbouring a menacing secret.

In one of the paintings, a fountain takes centre stage. The communist regime installed this fountain, which is now dismantled, in the midst of the fascist modernization project in the 1970s. Another painting has the boulevard spreading out over most of its surface, narrowing off in the distance. There are objects scattered on the road, as if left behind by people leaving in haste – perhaps after a riot or a violent confrontation. The road is lined by high trees, and above the verdant treetops there is a smudge of something that could be a drone or a hovering helicopter. Its ominous presence contributes to the subtly apocalyptic atmosphere that characterizes the suite as a whole.

Over the years, Bulevardi Dëshmorët e Kombit has been an important gathering point. During the communist dictatorship, it was used for parades and manifestations, such as to celebrate Dita e Çlirimit and remember the liberation from Nazi Germany in 1944. Another significant occasion was the 1st of May, International Workers’ Day. Later, the boulevard also became the stage for the fall of the communist regime, as well as for countless demonstrations and protests in the turbulent aftermath of the abrupt system shift.

The painting “Boulevard 6” (2015) depicts the building that currently houses the Prime Minister’s Office in Tirana. It was here, on 21 January 2011, that four demonstrators were shot dead during a protest against the abuse of power, corruption, and the widespread poverty and unemployment plaguing Albania. In front of the building’s rationalist facade, a monochrome black rectangle appears. If the painting were an official document, the blackness would resemble redacted information – a passage withheld from public view due to its explosive content. Positioned before the building and facing the street, the rectangle could also be interpreted as a billboard, once used for political slogans or commercial advertising. In this moment, however, all voices have fallen silent – everything has turned black.

At the time, Benito Mussolini’s urbanization project was meant to not only demonstrate the country’s ties to Italian culture and ideology but also break with the Ottoman legacy and reshape the identity of the Albanian people. The painting “Boulevard 3” (2015) features an abstracted version of the imposing university building, completed during 1942 – then known as the Casa del Fascio (House of Fascism). In Edi Hila’s interpretation, the lower rows of windows have been removed, as have the building’s entrances. This artistic move reinforces the feeling of impregnability; the facade appears as an impenetrable wall, while the open square below remains fully exposed to surveillance from the building’s upper floors. This enigmatic structure, with its latently violent aesthetic, effectively marks the end of the boulevard.

As a title, “Martyrs of the Nation Boulevard” raises questions regarding who, in fact, should be counted among the “martyrs of the nation”. When the boulevard got its name, it referred to the partisans and people in the resistance who had given their lives in the liberation struggle against fascist and Nazi occupying forces, thus paving the way for the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania. But in light of more recent historical events, who else might be considered a martyr of the Albanian nation?

In these paintings, different eras seem to coexist within a temporal vacuum. Manifestations of power are layered, one on top of the other, and the boulevard emerges as a dense material entity – where history and ideology have been compressed so tightly that they have fused into a shared sediment.

In the foreground of “Boulevard 3”, however, the traces of the earlier fountain structure have fractured into jagged surfaces that expose the underworld beneath. The cracks reveal a bottomless depth – perhaps a visual representation of the chasms that have swallowed victims of successive regimes and their claims to power. The darkness might evoke the fate of political prisoners who perished in underground cells, migrants lost at sea, or girls and women forced into prostitution. Perhaps it is within these depths that we might find the answer to the question of who should be remembered among the Martyrs of the Nation?

An Uncertain World

Permanent Instability was the title of Albania’s first international contemporary art exhibition, which was held at the National Gallery in Tirana in 1998. The exhibition’s curator, Edi Muka, formulated the title to describe the Albanian transitional period but also the more overarching situation in the Balkans. The region remained scarred by economic instability, the lingering trauma of war, and resurgent nationalism, while the rest of Europe appeared relatively prosperous, with stable democracies.

Nearly three decades later, the title seems once again highly relevant – as a reflection of our shared global reality. Wars, refugee crises, pandemics, climate change, and ecological degradation have shaped a world defined by uncertainty and rapid transformation. This state of unrest is also evident as a shift in Edi Hila’s artistic practice. Since the late 2010s, his gaze has increasingly extended beyond Albania, towards the world at large.

This shift can also be traced back to a specific event: one day, Hila buys a tent that can be mounted onto the roof of his car – a practical solution that allows him and his wife, Joana, to travel freely, linger in the most enchanting landscapes, and camp under the stars. Before long, however, news reports of escalating conflicts in the Middle East and harrowing images of the 2015 refugee crisis begin to seep into their holiday dreams.

When Hila later travels to Athens to prepare for his major presentation at documenta 14, he witnesses first-hand the arrival of large numbers of refugees and encounters their reality up close. The tent now assumes a new and unsettling significance. It enters his visual language as a symbol of a world in crisis – of lives teetering on the edge, searching for new places to take root.

In the painting “A Tent on the Roof of a Car “(2017), the tent and the upper parts of a car are silhouetted against a barren landscape. Faint traces of civilization emerge in the background, as hints of a densely built-up area. In “Newcomers” (2017), our eyes are led over the water along a pier. In the far distance, the stark white silhouette of what could be a tented refugee camp rises on the horizon – like a shimmering mirage against the murky water and sky.

The nomadic tent can be interpreted as an expression of a symbiotic relationship with nature – a home that breathes with the landscape. At the same time, tents, in a broader sense, embody the architecture of distress and survival – a last refuge when stability fractures and no alternatives remain. In the series “A Tent on the Roof of a Car”, the dream of freedom meets the reality of uncertainty. These paintings can be seen as harbingers of our shared future – one that will demand immense adaptability in the face of climate change and likely result in even greater waves of displacement than those we witness today.

This subtly apocalyptic tone also recurs in later painting series. During the pandemic year of 2021, Edi Hila explores the severe restrictions on movement and the experience of enforced isolation. In “Exit” (2021), he portrays an almost deserted airport. A few shadow-like figures linger within the labyrinthine fencing that, under normal circumstances, would have organized large flows of people. “Closed road” (2021) is similarly dominated by barriers. A stark whitewashed building rises like a monolith in the desolate landscape. Positioned behind erected fences, its closed facade appears as yet another impenetrable threshold – a sterile, clinical divide.

At this time, Edi Hila is preparing for several exhibitions. Due to the spread of the virus, he is confined to his home, where architectural models of various exhibition spaces become essential tools in his work. Over time, however, and as the monotony of isolation sets in, the model ceases to function merely as a spatial reference and instead emerges as the central motif in a series of paintings. In “From Above”, 2021), the model peeks out from beneath a round glass table, its sharp metal armature pinning it to the floor. In “Reflection on the Exhibition”, (2021), it stands before an armchair – where the artist has recently sat, contemplating his work in progress. The stillness of the room is charged with thought and reflection, yet it is also suffused with a palpable sense of solitude.

In both paintings, an initial sense of creative stagnation gradually gives way to a fascination with the shifting interplay of light and the delicate tonal nuances that emerge in the quiet monotony of isolation. Unlike previous series, which captured fleeting moments of Albanian street life or global phenomena such as migration and refugee crises, these works delve into an introspective process – offering a glimpse into the artist’s interior world.

Return to the Self

When Corinne Diserens and I meet Edi Hila in late autumn 2024, the artist has already turned eighty – yet he appears remarkably vibrant and full of creative energy. A profound shift has taken place in his life, one that has brought him both renewed joy and fresh inspiration for a new chapter in his work. Together with his wife, Joana, he has purchased his first house, nestled in a small mountain village near Pogradec.

The village is part of an old mining community, and the majestic mountains with their deep hollows have awakened an impulse in Hila to look both inward and downward. Inward – towards the depths of the soul and the uncharted landscape of the subconscious; downward – toward what lies concealed beneath the surface and deep within the earth.

The mine shaft testifies to the ruthless exploitation of nature and at the same time serves as a powerful metaphor for the systematic erosion of individuality. Just as the mountain was hollowed out to build modern Albania, Edi Hila – like so many others – was drained of his creativity and critical thinking. Without consent, he was compelled to serve an authoritarian regime and its ideology – a system that demanded total submission and stripped individuals of their autonomy.

Born in 1944, just a year before the founding of the socialist republic, Hila has lived a life shaped by Albania’s political extremes. He spent nearly half a century in Europe’s most isolated country – a Stalinist dictatorship where thousands of “enemies of the people” were executed, and fundamental freedoms, including movement and expression, were severely restricted. Over the following three decades, he experienced the turbulent and, at times, violent transition to a capitalist system – a period that opened doors to long-awaited freedoms but also revealed the many dark sides of consumer society.

Beyond the political upheavals that have profoundly shaped his work and his life, there is something deeply intrinsic and uncompromising about the man that is Edi Hila. A sentient being of flesh and blood, moulded by his history yet not entirely defined by it – a person who could only partly have become someone else if the historical circumstances had been different.

Through the window of Hila’s studio, we can see the tree-covered mountainside – an element that also appears in his sketches for future paintings. At the time of writing, this new series remains unfinished, with only a few works beginning to take shape. Yet in the photo-based sketches, a direction emerges. We see how mountain walls open to deep abysses, how fractured ground drifts in massive blocks like tectonic plates, over a sky that – somehow – has ended up below the earth rather than above it. We also see staircases so steep they trigger an instinctive vertigo, and I recognize them as the very steps leading down from Edi and Joana’s mountain paradise.

In the painting “Planting of Trees” (1971), Edi Hila masterfully evoked a communist idyll in a playful and inviting way – imbued with a vibrant joy for life and nestled within a pastoral, archaic landscape. This vision was never realized in Albania, and, ironically, it was this very painting that led to Hila being sentenced to a lengthy re-education process and banned from working as an artist.

When the regime’s grip finally eased and Hila experienced artistic freedom for the first time, he chose to capture the hope, confusion and brutality of the transition – the collapse of ideals and the hollow promises of consumer society. Today, his rich and profound body of work rises as a multifaceted monument to an era marked by hardship, fear, and violence – yet also one of resilience, enthusiasm, and creative exploration.

Without Edi Hila’s life’s work, the distinctive aesthetics of Albania’s transitional period – its atmospheres, scents, colours, and architectural imprints – might have been lost forever. His oeuvre has chronicled Albanian society at the rupture between worldviews and political systems. But perhaps the time has now come for Hila to turn his gaze inward.

Like the lone figure in Caspar David Friedrich’s Romantic masterpiece “Der Wanderer uber dem Nebelmeer” (1818), I picture Hila standing on the veranda of his whitewashed house. He gazes out over the towering mountains and the vast expanse of Lake Ohrid – one of Europe’s deepest and oldest lakes, home to a unique and ancient ecosystem. A life filled to the brim with human experience may, in time, become more attuned to that which lies beyond the human, more open to contemplation and introspection. I leave Edi Hila in this sublime mountain landscape and wish him well on his onward journey – toward the depths of the self and the earth.

Text: Joa Ljungberg

Translation: Bettina Schultz

Edi Hila

Edi Hila is widely regarded as one of Albania’s most significant artists – a painter who has captured his country’s dramatic social …

Fractured Horizons

Book a guided tour

Book a guided tour for your students, friends, colleagues or club. Experience an inspiring and dynamic environment, discover new perspectives and new …

Book a guided tour

Kafé Sisko

To have a snack and eat and drink something delicious in connection with the museum visit is unbeatable! Sit down in our café, Kafé Sisko, to …

Kafé Sisko