Julia Margaret Cameron, Suspense, 1864

Biographies

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879)

Julia Margaret Cameron was given a camera by her daughter when she was in her 50s, and she was active mainly in the 1860s and 1870s. Her staged photographs, inspired by myths, biblical stories, and English literature, have a characteristically expressive soft focus. Cameron’s photographs are reminiscent of the Pre-Raphaelites and Renaissance painting. She found her models among her family, friends, and servants. The Moderna Museet collection of Julia Margaret Cameron includes portraits of Charles Darwin, Henry Taylor, and Alfred Tennyson, along with staged tableaux of The Angel at the Tomb and the melodramatic Maud from one of Tennyson’s most famous poems. Cameron’s last major photographic project in the UK, before she and her family moved to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) was to illustrate Tennyson’s work Idylls of the King (1874–1875).

David Octavius Hill (1802–1870) and Robert Adamson (1821–1848)

The first prominent calotype practitioners were active in Scotland. David Octavius Hill was a portrait painter, and Robert Adamson an engineer. In 1843, they began collaborating as photographers, after Hill had been commissioned to portray a group of clergymen and laymen who had left the Church of Scotland and founded the Free Church of Scotland. Hill wanted to use photographs to create individual portraits of the several hundred participants in this assembly. It took them more than a year to produce a calotype of each member, and the painting took another 20 years for Hill to complete. They continued working together for four years, until Adamson’s premature death, producing nearly 3,000 photographs of architecture, landscapes, and especially portraits, which they always signed together. They also documented working women and men in the fishing village of Newhaven near Edinburgh in a natural and personal style that was unusual for that period.

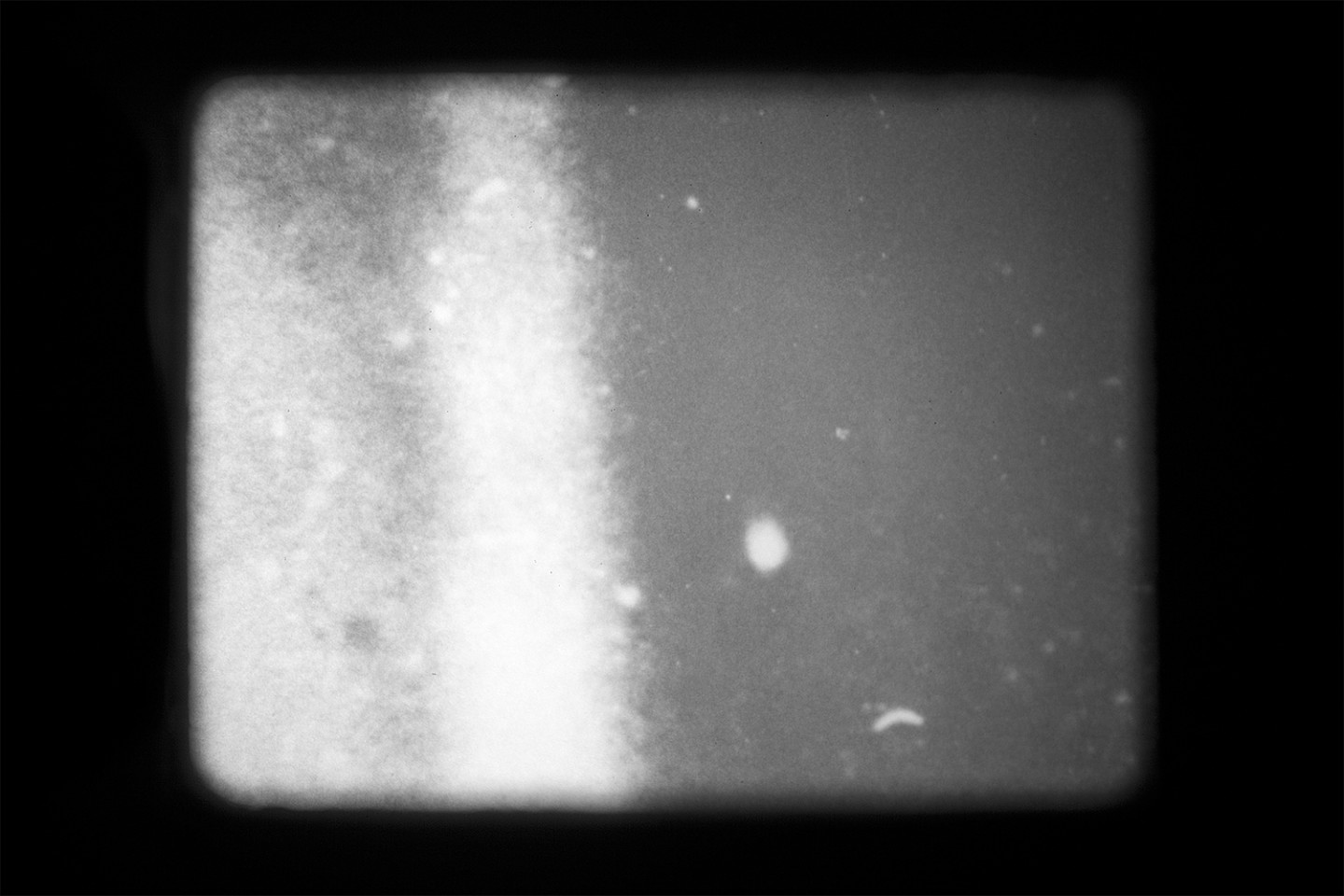

Joachim Koester (b. 1962)

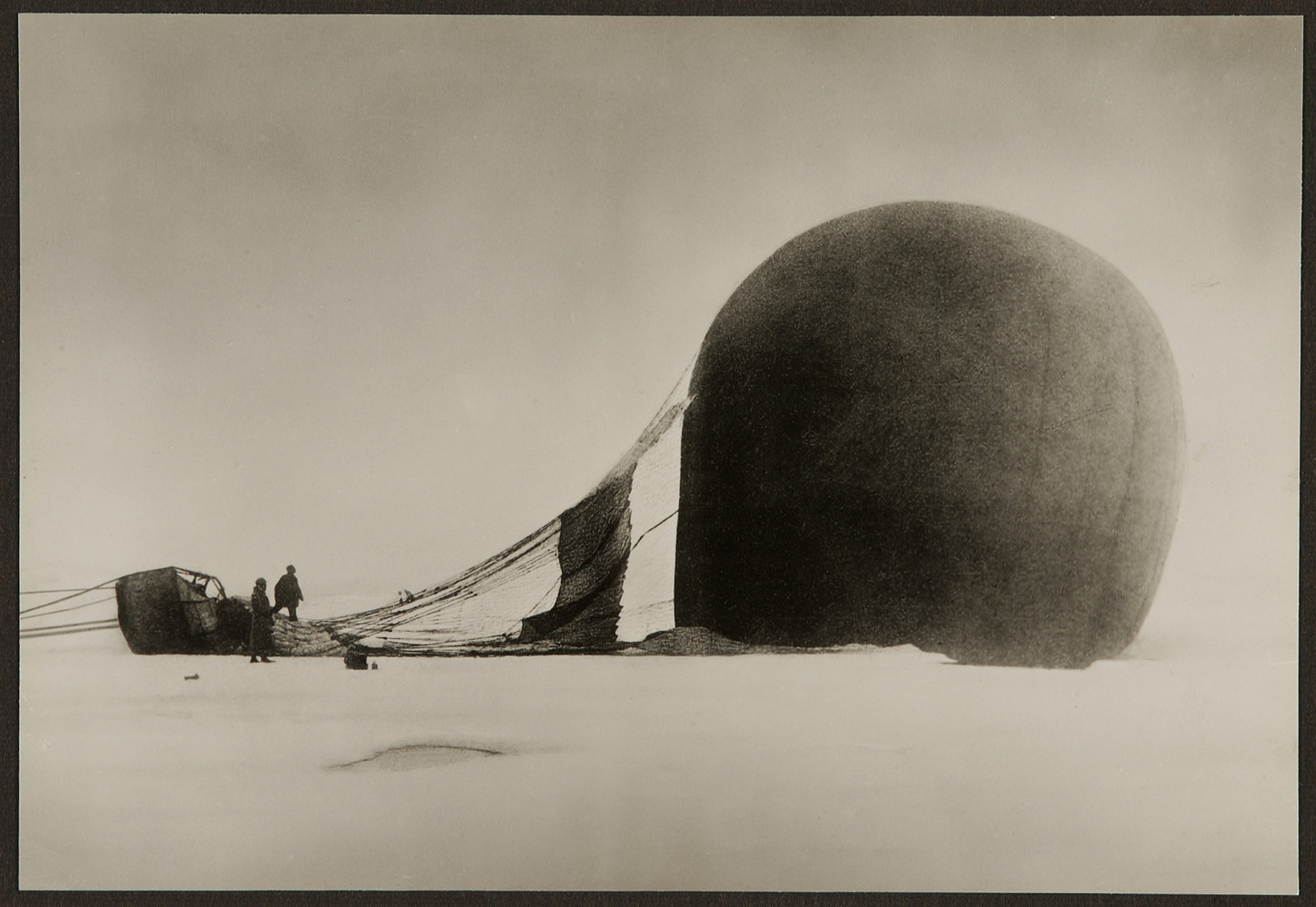

The Danish artist Joachim Koester’s work Message from Andrée (2005) borrows its visual material from Nils Strindberg’s rediscovered documentation of the Andrée expedition. Unlike many who have studied this material before him, Koester has chosen to focus on the elements on the actual surface of the photographs – stains, dirt, visual noise – rather than the purely narrative content of the images. What have these rolls of film experienced in the 30 years in the ice before they were found? What information lies in the layers between the narrative image and the visual noise? Is there a message from the polar expedition hidden in this gap? In this way, Koester focuses on an interesting time aspect, drawing our attention both back to the original moment when the pictures were taken, and to the future. In his study of Strindberg’s documentation, Koester operates between narrative and non-narrative, bordering the unknown.

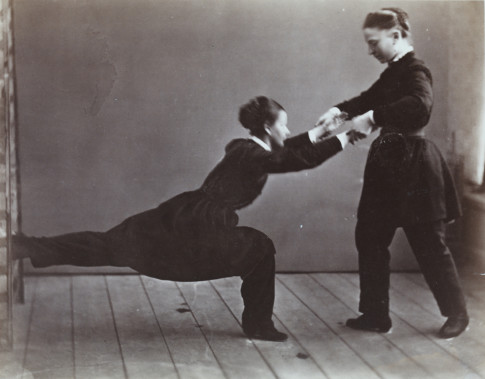

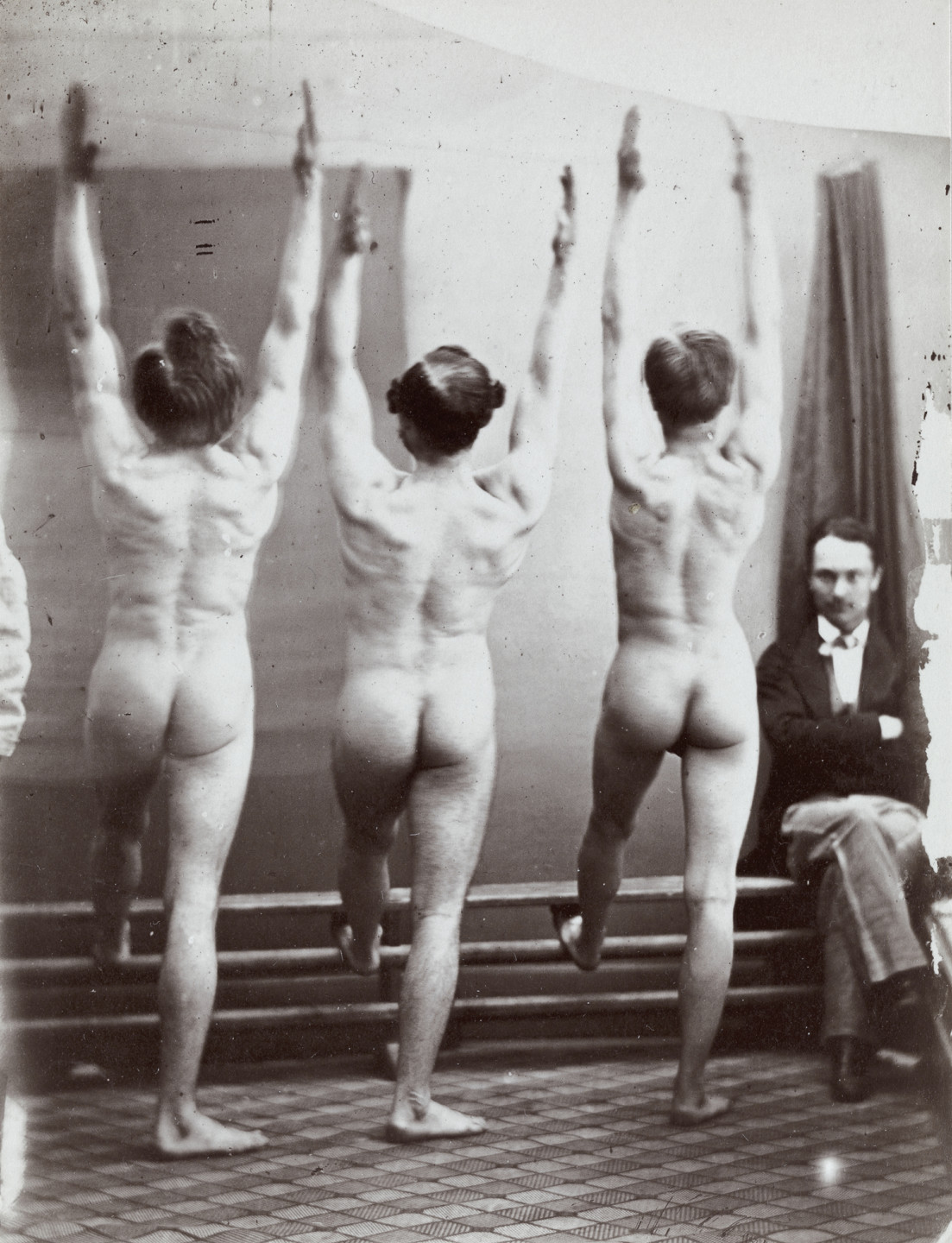

Carl Jacob Malmberg (1824–1895)

Carl Jacob Malmberg is a good example of a photographer’s career development after the first innovative period in the 1840s and up to the 1890s. Malmberg was born in Finland and first studied to be a goldsmith in St Petersburg, where he also learned photography. He moved to Stockholm, where he opened a studio in 1859 on Drottninggatan 42, later relocating to Norrtullsgatan 21, and finally to Regeringsgatan Around this period, when carte de visite portraits came into fashion, Malmberg’s practice really took off. On a visit to Finland in 1872, he made a series of photographs at Fiskars iron mill, documenting all the workshops and buildings. A slightly odd portfolio in Malmberg’s collection consists of more than 100 pictures of gymnasts. He had been commissioned by Hjalmar Ling at the Gymnastiska Centralinstitutet in Stockholm to take these pictures to illustrate the book Förkortad Öfversikt af allmän Rörelselära (Short Summary of General Exercise Physiology, 1880). The exhibition also presents a couple of daguerreotypes, the first successful photographic technique. It produces a sharp image, but only one copy resulted from each exposure.

Rosalie Sjöman (1833–1919)

Rosalie Sjöman was one of many prominent women photographers. She opened a studio in 1864 on Drottninggatan 42 in Stockholm, after being widowed with three small children. The photographer Carl Jacob Malmberg had had his studio at this address previously, and there are some indications that Sjöman may have worked for him. Her business prospered, and towards the end of the 1870s Rosalie Sjöman had five female employees. She seems to have chosen to hire women only. R. Sjöman & Comp. later opened studios on Regeringsgatan 6, and in Halmstad, Kalmar and Vaxholm. Her oeuvre includes numerous carte de visite portraits and larger so-called cabinet cards, with a mixture of classic portraits, various staged scenes, people wearing local folk costumes, and mosaics. The expertly hand-tinted photographs are especially eye-catching; several of them portray her daughter Alma Sjöman.

Carte de visite was introduced in France in the mid-1850s, but became extremely fashion able after 1859, when Emperor Napoleon III had his portrait made in the new format (9×6 cm). In the 1860s, photography progressed from being an exclusive novelty into a more widespread and popular medium. The trend of carte de visite spread rapidly, and portrait studios opened in large cities and smaller towns. This cartomania lasted for a decade, and the market stabilised around the mid-1870s, when the photographic medium entered a calmer phase.

Nils Strindberg (1872–1897)

In July 1897, the Swedish engineer and explorer Salomon August Andrée (1854–1897) embarked on his voyage to the North Pole in the balloon Örnen (The Eagle), accompanied by the engineer Knut Frænkel (1870 – 1897) and the photographer Nils Strindberg. A few days later, the balloon crashed on the ice, and they were forced to continue their journey on foot. The conditions were severe, and the expedition ended in disaster. After a few months, in October, they made up camp on Kvitøya on Svalbard. This is where their bodies were found thirty years later, along with Strindberg’s camera. The expedition and the events surrounding it were widely publicised, both at the time of the expedition, and later when they were found. Per Olof Sundman’s book The Flight of the Eagle (1967) was turned into a film by Jan Troell in 1982, and in 2015 the English version of Bea Uusma’s book The Expedition: a Love Story was published. Although these photographs were taken as scientific observations, and to document the work of the members of the expedition, they now appear as some of the most remarkable and beautiful photographs in polar history.

John Hertzberg (1871–1935) was a photographer and docent at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. He was commissioned to develop the exposed films, and managed successfully to process ninety-three of Strindberg’s photographs. He made copies of the negatives, which were used to produce the prints on paper that are now in the collections of several institutions, including Moderna Museet, the National Museum of Science and Technology in Stockholm and Grenna Museum – Polarcenter in Gränna. The original negatives ended up at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm. Hertzberg retouched some of the pictures, and these are primarily the ones that have been published and embody the public perception of the expedition. Moderna Museet owns both sets, and the retouched photographs are shown above the unretouched versions in this exhibition.

Carleton E. Watkins (1829–1916)

Voyages of discovery, nature and landscapes were popular subjects for the early photographers. Growing tourism increased the demand for pictures of remote places, making this a source of income for publishers of photographic literature. Western USA was one such region, and a few of the photographers who began working there also documented the American Civil War. One of the most prominent of these was Carleton E. Watkins, who had travelled and photographed the Yosemite Valley on several occasions in the first half of the 1860s. His large-format photographs, so-called mammoth plate prints, capture the massive mountain formations, dramatic waterfalls, and gigantic trees. The heavy equipment was carried by some ten mules, and it is almost a miracle that so many of his photographs survived, considering the difficult conditions.