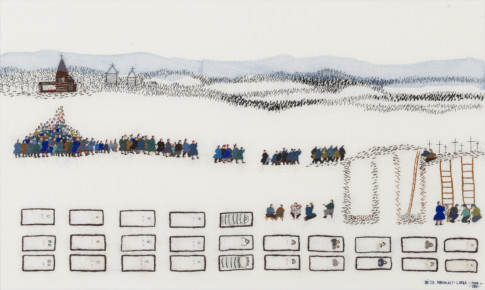

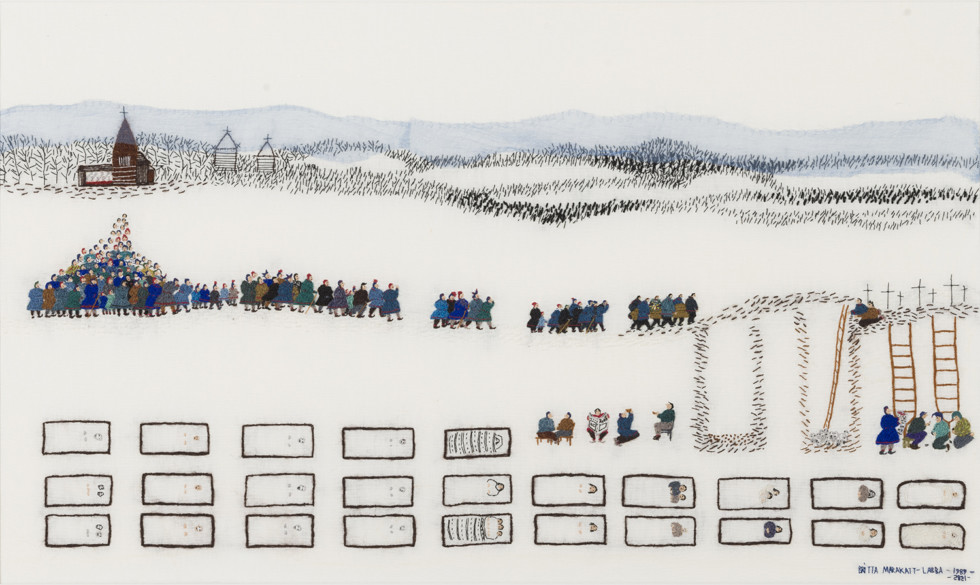

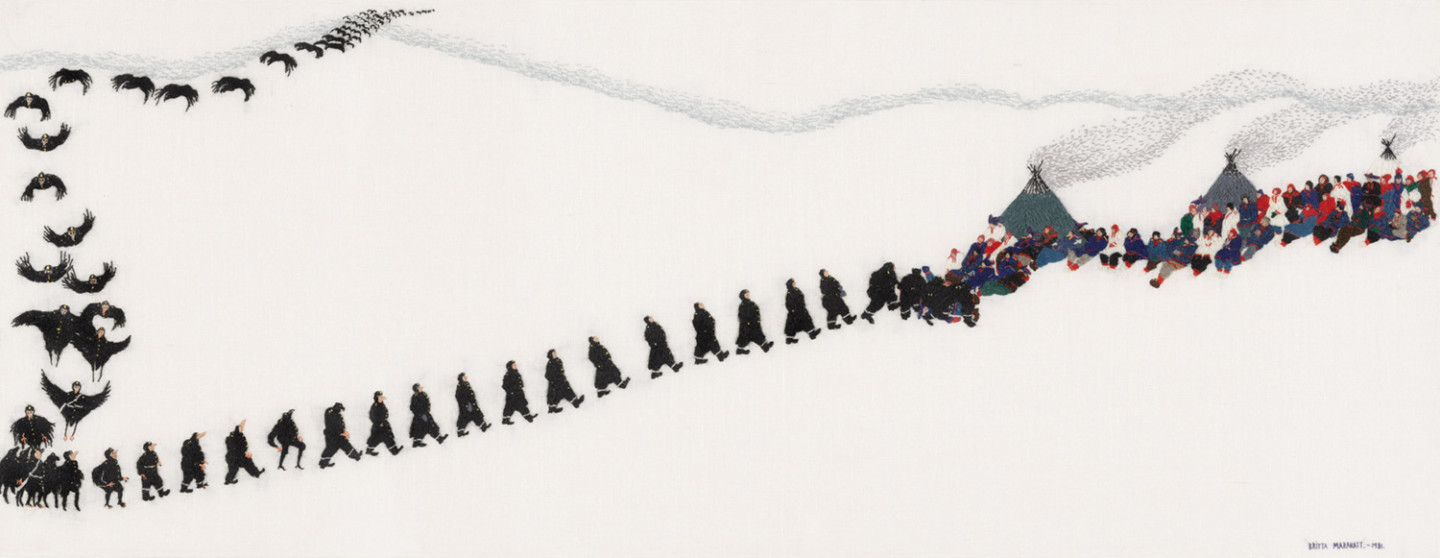

Britta Marakatt-Labba, Mátki II (The Journey II) , 1989/2021 Photo: Tobias Fischer/Moderna Museet Bildupphovsrätt 2024

A conversation between Britta Marakatt-Labba and Matilda Olof-Ors

Conversation

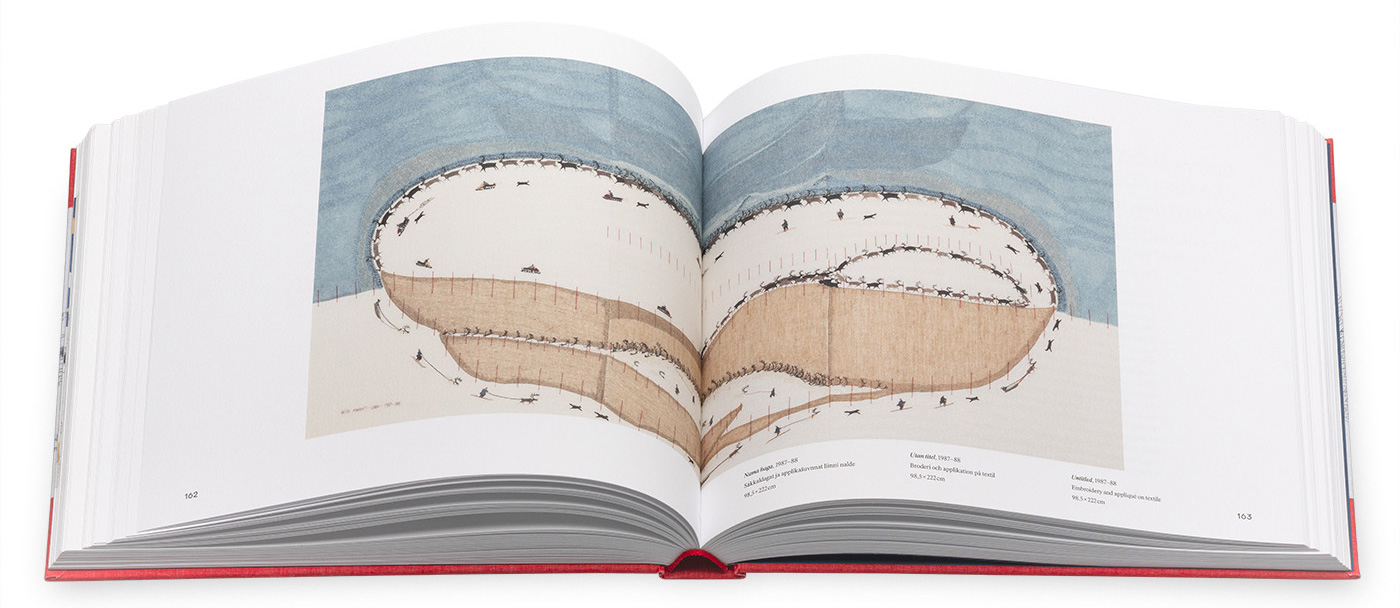

Exhibition catalogue, Swedish/English/Northern Sami. Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

Matilda: I would love to begin by discussing the title of the exhibition, “Where Each Stitch Breathes”. It comes from one of your texts, the introduction you wrote to “Broderade berättelser” (Embroidered Stories) from 2010, a book edited by Jan-Erik Lundström. As I was reading your introduction, which we’re lucky to reprint in this catalogue, I was especially struck by these sentences: “To embroider is to engage in an aestetics of deliberate slowness. It is a voyage in time and space where each stitch breathes experiences and insights, forming narratives.”

To me, that is such a good and poetic description of your work and practice. You’ve been active as an artist for almost fifty years now. Your stories build on these tiny, tiny units that are the stitches. Each stitch holds and breathes experiences and contemplation, qualities that enter into the most miniscule components of the stories. I’d be curious to hear more about the role of storytelling in your pictures.

I remember thinking: “I’ve got it, now I know exactly.” I work like a painter, but I don’t paint on canvas like an oil painter. Instead I choose textile canvases of various structures. Then I paint, or draw, using needle and thread.

Bildupphovsrätt 2025

Britta: When I started to think about how I want to work with pictures, I thought about the central role that storytelling has always played for Sámi. In my home we told stories all the time. I also thought about the objects we used in our daily life: a knife, a sheath, a spoon, the vessels we drank our coffee from – all were richly decorated with ornaments, sometimes with little stories. My dad had engraved our saltshakers by carving fine lines with the tip of a knife, so fine that you can see how the man skiing after a reindeer is smoking a pipe and the smoke rising from it.

It’s beautifully done. It made me think that perhaps I’ve inherited my storytelling from him, since he was so good at what he did with those everyday objects. But aside from what I’ve mentioned here, there aren’t a lot of visual storytellers among us Sámi, so I had the idea of telling stories using pictures. Of course I had all those pictures inside of me since I already had the stories. But I had no idea how I wanted to make them. In terms of materials, I knew I wanted to work in textiles; I’d grown up with Sámi duodji, and textiles are close to my heart.

It’s not just been the soft materials, however. I had two older brothers, one of whom was constantly carving and cutting wood. My other brother told his stories using a camera, documenting life as a reindeer herder, capturing both people and animals, the hunt and the fishing.

Britta: It took me maybe ten years to land on embroidery. It was during my time at HDK (the School of Design and Crafts at the University of Gothenburg) and I remember thinking: “I’ve got it, now I know exactly.” I work like a painter, but I don’t paint on canvas like an oil painter. Instead I choose textile canvases of various structures. Then I paint, or draw, using needle and thread.

Once I’d found my method, and embroidery as my material, all I had to do was get to work. I was also supported by my brother’s old photographs, which I studied closely.

Matilda: So you looked at them for inspiration?

Britta: Yes, and I still have them. I inherited them from him, his old contact prints and everything, they’re beautiful. We used his black and white photos for my film, Historjá (Stitches for Sápmi, 2022).

Bildupphovsrätt 2025

Today a lot of my work deals with what’s happening with the climate. We talk about climate change, though at this point I’d say it’s more of a… catastrophe. It’s not change anymore, but a lot of things are happening.

Matilda: What sorts of stories do you want to portray, and where do they come from?

Britta: When I was first starting out, I felt it was important to talk about daily life: this is what it’s been like for us, this is what it’s like today, though we can’t know about the future. Then I started to do more political stories and events. My mother’s stories were a great help in this; she would ascribe a political dimension to various animals. She might not have thought exactly along the lines of, this is political, when she mentioned, for instance, that crows are like the powers that be: if you toss anything to a flock of crows you can bet it will be picked clean by the time they’re done with it. And it’s true, of course, they’ll devour anything.

Britta: It’s like when I came to Alta in the early 1980s to demonstrate against the damming of the Alta river. I was there, you know. I wanted to really show that it’s not right to start damming rivers that flow freely. I saw the Norwegian police when they came over the mountain. There were 600 of them, a whole big mob, and suddenly I recalled my mum’s story about the crows. “Yes, here come the crows,” I thought.

If I have an idea today it might take me years to realise it. But in this case I had to go for it; I knew that this was it.

Bildupphovsrätt 2025

Britta: I made “The Crows” (1981) very quickly. Otherwise I tend to be kind of slow. If I have an idea today it might take me years to realise it. But in this case I had to go for it; I knew that this was it. That’s where the politics came in. After a while I realised that politics sits very close to mythology, and that’s where the mythological stories of my childhood came in, partly from my mum, partly from my father’s father.

Today a lot of my work deals with what’s happening with the climate. We talk about climate change, though at this point I’d say it’s more of a…catastrophe. It’s not change anymore, but a lot of things are happening.

These different parts shaped how I started my work. And where I am today; a lot of it is about what’s happening today.

Matilda: So daily life and the myths, it’s all intertwined somehow?

Britta: Yes. And then this thing with the wind farms that are being built. Taking more and more land from reindeer-herding Sámi. In my area there’s a lot of prospecting going on all the time, too. They find new minerals, not far from me as the bird flies – just fifty kilometres off they’ve found graphite, which is needed in our cell phones. And in Lannavaara they’ve found cobalt, and that’s not even ten kilometres away. Cobalt is one of the most polluting minerals you can dig for.

The conversation between Britta Marakatt-Labba and the Moderna Museet curator Matilda Olof-Ors took place at Moderna Museet in Stockholm on September 25, 2024.

Read the full conversation in the exhibition catalogue “Britta Marakatt-Labba – Where Each Stitch Breathes”. You can find it in the Moderna Museet Shop – on site in the museum, or here in our online shop.

Exhibition catalogue, Swedish/English/Northern Sami. Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet