Karl Isaksson, Young Samuel Is Taken by His Mother to High Priest Eli, uå Photo: Moderna Museet

About the works in The Man with the Blue Face

Sigrid Hjertén, The Brunette and the Blonde (1911)

Two figures lost in their own worlds. One of them – the brunette – is bending her head and looking down, perhaps at a book. The other one – the blonde – is sitting with crossed legs, her torso twisted in our direction. Distractedly she regards her nails while her thoughts move freely. The light falls on her bared shoulder area, caresses the smooth skin of her neck and illuminates one side of her face. Her skirts, gathered at the waist, reveal legs clothed in blue tights. Their diagonals and curves work together in a rhythmic interplay across the picture surface.

For Sigrid Hjertén, 1911 was an eventful year. After completing her studies at the Académie Matisse in Paris she returned to Stockholm in the late summer. In a small studio on Engelbrektsgatan 4 she applied what she had learnt in the French capital, with her paintings from the time testifying to the strong influence of both Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse. The year 1911 was also eventful for other reasons. The stomach pains that Hjertén had suffered from for a while proved to be caused by pregnancy. On 9 November she married Isaac Grünewald and seventeen days later their son Iván was born.

Can we – despite the feminine traits of both figures – interpret the ”Brunette and the Blonde” as Isaac and Sigrid? Isaac sitting in the wicker chair and Sigrid as the blonde. The red curtains on the right side of the picture bring to mind the theatre. Perhaps the painting captures a moment of meditative rest between two acts: between youth and adulthood, or between a life as freely searching modernist pioneers and a life as parents, responsible for a child.

Sigrid Hjertén was born in 1885 in Sundsvall and died in 1948 in Saltsjöbaden, Stockholm.

Isaac Grünewald, The Author Ulla Bjerne (1916)

The writer Ulla Bjerne moved in intellectual circles in 1910s Paris. She was famously charming and often dressed like a man, in a necktie and jacket. In his full-length portrait of Bjerne, Isaac Grünewald emphasised her tomboyish – garçonne – characteristics, depicting her standing wide-legged, with her hands stuffed in her pockets. Although her narrow waist is emphasised and her shoes are dainty, her gaze is curiously observing and the viewer encounters this new modern woman as a confident conversation partner in the salon.

In another painting by Grünewald, the artist’s son Iván is shown sunk in thought, leaning against an armchair. The surrounding room is painted in a russet tone that makes the furniture and walls merge. Two spots of light have, however, found their way in, as if entering through a gap or a wormhole in the curtains. Like bubbles filled with light, the largest spot falls against the backrest of the armchair and the boy’s torso, while the smaller spot has landed on a section of the carpet. As if by magic, quite different colours and moods emerge within their thin membrane.

Isaac Grünewald became one of the most colourful proponents of modernist painting back home in Sweden. The fact that he had Jewish parents, who had immigrated from Eastern Europe was, however, eagerly emphasised by the opponents of the new aesthetic. They portrayed both Grünewald himself and the Paris-inspired art that he advocated, as “foreign” and “un-Swedish”. Despite these attempts to diminish his work, Grünewald became a key figure in the breakthrough of Swedish modernism.

Isaac Grünewald was born in 1889 in Stockholm and died in 1946 in an aeroplane crash near Oslo.

Tora Vega Holmström, Boy with Seashell (ca. 1918)

A young boy is holding a shell against his ear, listening to its eternal noise. His beautiful and androgynous features resonate with the undulating lines in the light background. He seems to be somewhere beyond time and space; on the verge between dream and reality and in a place imbued with spiritual purity.

In the first half of the 1910s, Tora Vega Holmström painted in a mosaic-like style, using vivid colours. Towards the end of the decade, she had moved on to a much whiter palette and an almost ascetic expression. ”Boy with Seashell” was conceived in different versions during her stay in Vindeln, in northern Sweden in 1918. Snow-clad landscapes with intensive light and crisp air may have inspired the white and sacred expression. The war years may also have had an impact, by triggering a longing for the pure, the untainted, and for abiding values. In the paintings from this period, a kinship with Italian fresco painting emerges, which Holmström had studied in Florence in 1910.

While many of her Nordic fellow artists were apprentices of Henri Matisse in Paris, Tora Vega Holmström instead studied under Adolf Hölzel in Dachau, near Munich. Hölzel lectured on the intrinsic value of colours and the relationships between them. He spoke of harmony and counterpoint. In general, he liked to use musical terms, and argued that lines and shapes in visual art corresponded to rhythm in music. In her many meditations on colour drawn in pastels, Tora Vega Holmström explores tonality and resonance, gradually moving towards abstraction.

Tora Vega Holmström was born in 1880 in Tottarp, Skåne. She died in 1967 in Lund.

Henri Matisse, Two Odalisques, One of Which is Naked, Ornamental Background and Checkerboard (1928)

Henri Matisse became the figurehead of the French expressionists – Les fauves. These “wild animals” of art held painterly values higher than realistic depiction. By simplifying the motif, they wanted to emphasise that which was essential. They embraced the emotional resonance of colours and lines and sought a form of personal expression. With bold colours and rough brushstrokes, their painting can appear as a radical extension of Vincent van Gogh’s Postimpressionism.

The influence of a variety of African and Oceanic cultures and artefacts was decisive for the development of expressionist painting in France as well as other parts of Europe. Henri Matisse’s sojourns in Morocco and Algeria inspired his rich use of patterns, vivid colours and undulating lines. His travels also had an impact on his choice of motifs, which is evident in his many paintings of “odalisques” – inspired, according to him, by visits to Moroccan harems.

The tradition of the harem painting can be traced back to artists such as Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867). In recent decades, the genre has met with growing criticism. Its questioning in part reflects a feminist awakening, and in part an increased awareness of how Western art developed in an interplay with colonial occupation. The colonial context, that Matisse and his fellow artists lived and worked within, may emerge as particularly provoking in erotic fantasies involving the “conquered” Other.

Henri Matisse was born in 1869 in Le Cateau-Cambrésis in France. He died in 1954 in Nice.

Nils Dardel, Portrait of Einar Jolin (1913)

In the spring of 1912, Nils Dardel left Paris to travel north to Senlis, where he checked in at the homey Hôtel du Nord. Here he managed to assimilate the impressions from the French capital and forge his own artistic language. We see it emerge in ”Portrait of Einar Jolin”, in which his fellow artist and friend sits in a red velvet armchair, immersed in his daydreaming. The richness of patterning in the curtains, carpet and wallpaper combines with the pointillist-inspired painting style in generating a vibrant atmosphere of life and creative presence. At the same time, the painting radiates a casual intimacy and calmness.

In Senlis Nils Dardel socialised with the writer Ulla Bjerne, who is portrayed in Isaac Grünewald’s painting in this exhibition. Another close friend of Dardel’s was the art collector (and later director of the Swedish Ballet in Paris) Rolf de Maré. They travelled to Tunisia and Algeria together in 1914. Upon his return, Dardel painted ”Reception”, which depicts a gathering in the oriental-style salon on de Maré’s family estate in Hildesborg, near Landskrona in southwestern Sweden. The host is just entering the room, while Dardel is depicted sitting on a chair, dressed in blue.

In Nils Dardel’s work we can detect inspiration from late Medieval miniature painting and from Postimpressionist artists like Pierre Bonnard and George Seurat, the latter known for his systematised pointillism. Dardel was also influenced by naive painters such as Henri Rousseau. Based on these impulses, he created something entirely unique, which also included a playful exploration of the queer transgressiveness.

Nils Dardel was born in 1888 in Bettna, Södermanland County, Sweden. He died in 1943 in New York.

Ninnan Santesson, Monsieur Iffa* (1914–17)

Just like many other aspiring artists at the time, Ninnan Santesson was critical of the conservative education offered at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Art in Stockholm, where she studied between 1911 and 1913. Therefore, she soon travelled to Paris to further her studies, accompanied by her classmate Lisa Bergstrand. Later, Siri Derkert also joined them.

In Paris, Ninnan Santesson attended life drawing classes at the Académie Colarossi and studied sculpture under Antoine Bourdelle. She spent the winter of 1914 in Algeria with Lisa Bergstrand and Siri Derkert. It’s possible that it was here that Santesson met Monsieur Iffa, who is portrayed in her gilded sculpture. His serious face has a solemn beauty, and the fact that the finely carved wooden surface is accentuated by gold, contributes to the impression of a man who is esteemed and respected. Neither the photographs that have been preserved from the trip nor Santesson’s letters, however, give any clues as to who this Monsieur Iffa was.

Apart from the public artworks that Ninnan Santesson completed the 1920s in Gothenburg, she mainly sculpted portraits of people (heads), and rarely exhibited her work. She kept to her closest circle of artist friends and family, and created intimate portraits of them, especially of her daughter Lena, who, thirteen at the time, could have been the model for ”Girl’s Head”. Towards the outbreak of the Second World War, Santesson became increasingly politically active. She helped refugees from Nazi Germany and among those who were offered refuge in her home was Bertolt Brecht and his family. She also got involved in the Norwegian resistance movement and was imprisoned in Sweden for two months under charges of espionage.

Gertrud Paulina (Ninnan) Santesson was born in 1891 in Fjärås in Halland County. She died in 1969 in Stockholm.

*The sculpture ”Monsieur Iffa” was registered in Moderna Museet’s collection under the title ”Nxxxx Head” for some time. There is however nothing to indicate that this was the title that the artist herself gave the work. When the sculpture was exhibited in 1917 it bore the name ”Monsieur Iffa”, which is now the only registered title of the work in the museum’s database.

Edvard Munch, Girl at the Bedside (1916)

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch exerted a strong influence internationally and inspired many expressionist artists, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. ”Girl at the Bedside” was probably painted in Ekely in Norway, where he settled after an itinerant life in Europe and lived until his death.

In art historical texts, ”Girl at the Bedside” has been interpreted positively as expressing an awakening sexuality – unnerving, bewildering and with blushing cheeks. The girl has been described as relaxed, and the artwork has even been praised as an homage to life.

Seen in a different light, however, the same painting can communicate a teenage girl’s embarrassed shyness and vulnerability while posing completely naked for a much older man. Seen from this perspective, the stiff posture and the tensely staring gaze could indicate the girl’s attempt at taking charge of the situation, partly by detaching herself and going somewhere else in her mind, and partly by avoiding all forms of movement that would further charge the situation.

No matter how we interpret the work, the psychological atmosphere of the image is of central importance. Rather than only depicting reality as it appears to the eye, Munch seemed to want to capture a state of mind and a mood. And perhaps the one interpretation does not completely exclude the other.

Edvard Munch was born in 1863 in Ådalsbruk near Løten in Hedmark County, Norway. He died in 1944 on the estate Ekely near Oslo.

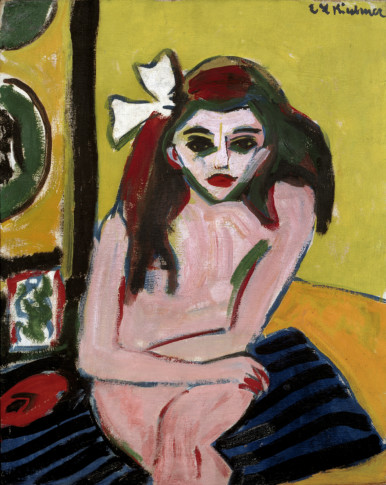

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Marzella (1909–10)

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s ”Marzella” was painted in the artist’s studio in Dresden. The portrayed girl is most certainly Lina Franziska Fehrmann, at the age of ten. She was the youngest of twelve siblings, of which eight survived, in a Dresden working-class family. At the age of eight, she had begun modelling for several of the artists that in 1905 had formed the expressionist group Die Brücke. She also joined these artists to the countryside, as they, in the summer months of 1909 and 1910, left city life behind, in order to explore a more natural and uninhibited way of life around the Moritz Lakes.

Art historical texts about ”Marzella” have often stressed the sketchy drawing and the bold colours, as well as the fact that the girl meets the viewer’s or the artist’s gaze, as if she is challenging her objectification. The girl’s pre-pubescent body has also been interpreted as a vessel for the longing of the Die Brücke artists for naturalness and unaffectedness. They sought liberation from the bourgeois conventions and customs, not least within the sexual domain, making the not-yet-grown girl particularly interesting since her sexuality was considered unformed.

In recent years, new information has surfaced which supports the belief that the de painted girls, alternatively referred to as Fränzi and and Marzella, are in fact one and the same child. The paintings have also been examined more from the perspective of the girl: What was it like to stay with a group of experimenting adults without the presence of her parents and siblings? Did she feel safe? Was she happy? And how come the vulnerable position of this child has not been addressed by critics and interpreters of previous generations?

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was inspired by Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Edvard Munch. Another portrait of Marzella from 1910 bears distinct references to Munch’s work ”Puberty”, which is also in this exhibition. The girl in ”Puberty”, however, seems alone with feelings that overwhelm her, while Kirchner’s ”Marzella” interacts with the artist and the viewer in quite a different way.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was born in 1880 in Aschaffenburg in what was then the German Empire. After harassment and persecution from the Nazis in the 1930s, he chose to end his life in 1938. He died in Davos, Switzerland.

Karl Isakson, Young Samuel Is Taken by His Mother to High Priest Eli (undated)

In this undated painting by Karl Isakson we see a child being led towards a seated older man. The child is naked, its facial features impossible to make out, but his exposed skin and posture testify to a strong feeling of vulnerability.

The painting was inspired by the Bible story about the boy Samuel who was handed over to the temple as a gift to God. Samuel’s mother Hannah had long been suffering from childlessness until one day she promised God that if He blessed her with a child she would in turn hand the child over to Him. The High Priest Eli who witnessed her desperate prayer, called out “may the God of Israel grant you what you have asked of Him.” Shortly thereafter Hannah fell pregnant and gave birth to Samuel. The boy spent his first years with his mother who thereafter handed him over to the temple. The painting captures the moment in which Samuel is stripped of everything he knows and his entire sense of security while entering into a foreign context.

Karl Isakson grew up poor with a deeply religious mother, and Bible study was probably a frequent occurrence at home. While biblical motifs recur in different periods of Isakson’s artistic career, this does not necessarily reflect the artist’s religious beliefs but rather appears to be a method of exploring emotional experiences and existential issues.

Karl Isakson studied under the Danish painter Kristian Zahrtmann. After completing his studies, he chose to stay in Denmark, in whose artistic circles he felt more comfortable. He was born in 1878 in Stockholm and died in Copenhagen in 1922, a mere forty-four years old, in the aftermath of a bout of pneumonia.

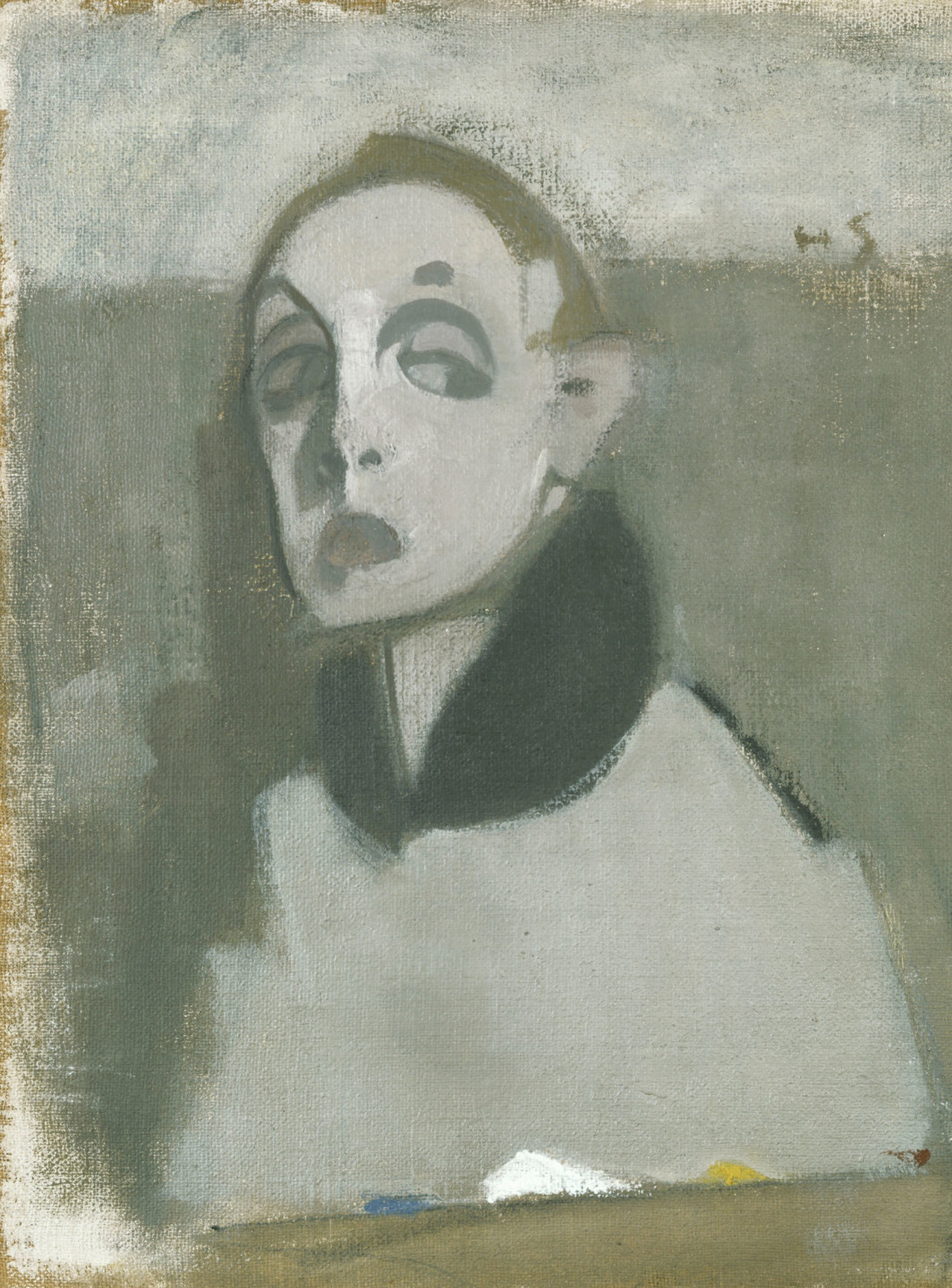

Helene Schjerfbeck, Self-Portrait with Palette (1937)

Helene Schjerfbeck is examining herself in the mirror. Her facial expression attests to deep concentration but also suggests a sense of alienation from her own reflection. Is she still the same, despite her features having changed with age? Depicted in the twilight state of ageing, the greyish tones make the artist emerge as if out of a gloom.

A few spots of bright colour – blue, white and yellow – contrast with the otherwise dominating greyness. They lie squeezed onto the artist’s palette, which seems to have fallen outside of the mirror’s reach. Perhaps the colourful spots can be interpreted as traces of contemporary life and the intensity of youth, from which Helene Schjerfbeck, at the age of seventy-five, has increasingly distanced herself.

Schjerfbeck began her career in the nineteenth century’s naturalistic and historicising style, but developed a finely tuned, sensitive expressionism at the beginning of the twentieth century. In the 1880s and 1890s she spent some time in Paris, and after her first solo exhibition in Helsinki in 1917 she embarked on further study trips to France, England, Russia and Italy. Back home in Finland she mainly lived a withdrawn life, dedicated to art.

Schjerfbeck’s many self-portraits became aesthetically pared-down and ascetic with age. Transience is at the heart of her unique series of self-studies, in which we ultimately witness the near complete dissolution of colour and form. In the final portraits, we can almost perceive how the artist draws her last breath.

Helene Schjerfbeck was born in 1862 in Helsinki. In the war years she was evacuated to Saltsjöbaden outside Stockholm, where she died in 1946.

Ellen Thesleff, Golden Bird (1939)

Surrounded by the spring air and the chirping of birds, two featherily and spontaneously painted figures emerge next to a tree. The tree’s branches are still bare, but in the lower left-hand corner, three white spring flowers are blooming. It is hard to make out whether the woman in the middle of the image is offering the contents of her basket, or if, on the contrary, she is lifting her hands to chase away cheeky birds. The bird that is visible against the sky on the left seems, at least, to have gotten hold of a twig with golden flowers.

The year before Ellen Thesleff painted her ”Golden Bird”, she had succeeded in selling several artworks, making it possible for her to embark on another journey to her beloved Florence: “I’m travelling with my money – in order to earn more money – I want to paint among the hills of Florence once more.” This trip was to be her last. Accompanied by her sister Gerda and her niece Elisabeth, she got to once again experience Italy’s budding spring – the return of life. The war was drawing closer, however, and already in May the group was forced to travel home to Finland.

Ellen Thesleff started her artistic career in a naturalistic style rooted in the realism of the 1880s, but after the turn of the twentieth century she developed a finely tuned lyrical expressionism. The thin yet broad lines of her bold brushstrokes support the evanescent forms that are on the verge of being absorbed by the surrounding air. As a critic poetically wrote about Thesleff’s work in ”Svenska Pressen” in 1934: “Everything in this work is movement and light. The compositions are like clouds that one moment form figures and scenes and the next seem to be merely graceful undulations in the dissolving skies.”

Along the bottom edge of the painting a name can be discerned – “Rolf”, the artist’s recently deceased brother. Ellen Thesleff was born in 1869 in Helsinki, and died there in 1954.

Åke Göransson, Eva (1930–32)

Åke Göransson stands out as one of Swedish modernism’s most idiosyncratic colourists. He studied with artists like Karin Parrow, Ragnar Sandberg and Ivan Ivarson under Tor Bjurström at Valand Academy. With experience of both the Danish and the French art scenes, Bjurström spurred his students on to develop their own personal aesthetic and uninhibitedly explore the possibilities of colour. His tutelage inspired a generation of innovative painters in the 1920s, often referred to as the Gothenburg Colourists.

Despite his obvious talent, Åke Göransson’s life was impoverished, hard and much too short. He died a mere forty years old, suffering from severe tuberculosis and schizophrenia. In his years as an artist, he managed, however, to create several paintings that have continued to fascinate and amaze. He told those close to him that he tried to arrive at something he called “färgformen”, the colour-form, which, according to him, distinguished itself from “sinnesformen”, the sense-form, through its rootedness in an inner reality.

In the 1930s this inner reality started to take over as Åke Göransson became increasingly mentally ill. When he painted the works ”Eva” and ”Sleeping Man”, his health was already badly deteriorated. The art critic Tord Bäckström has poetically described Göransson’s paintings from this period as showing a “growing distance between the seer and the seen, as if the artist took pains to capture a reality that had already decamped and left him.”

Åke Göransson was born in 1902 in Veddige, Halland County, but lived most of his life in Gothenburg. In 1937 he was admitted to Lillhagen Hospital, where he remained until his death in 1942.

Karin Parrow, Långedrag (1937)

Karin Parrow’s landscape painting ”Långedrag” presents itself like an exalted musical interplay of colours. The clear resonance of the tones – in green, purple and orange – sings from the canvas. The image also carries a pull inwards, amplified by the long purple brushstrokes along the road disappearing in the depths of the landscape. The eye acquiesces, passing the vertical poles of the lampposts, like a melody weaving through a musical stave. If we, instead, lift our gaze to the fiery sky, this forward motion abates, allowing our eyes to rest on the landscape.

Karin Parrow was part of the circle of artists often referred to as the Gothenburg Colourists. They had all studied under Tor Bjurström at Valand Academy and distinguished themselves with their free and bold exploration of colours. Encouraged by their Paris-taught mentor, they developed a style of expressionist painting based on sensual and poetic colour experiences, in which form often played a subordinate part.

Although Karin Parrow exhibited regularly and her work often garnered positive reviews, she has frequently been omitted from texts about the Gothenburg Colourists. Art history has paid much greater attention to her male colleagues, like Ivan Ivarson, Inge Schiöler, Åke Göransson and Ragnar Sandberg. Parrow shares this fate of being overshadowed by the male artists of her time with many other talented women. In recent decades, however, interest in female modernists has grown and with it, recognition of Karin Parrow’s painting.

Karin Parrow (née Taube) was born in 1900 on the island Vinga in Gothenburg’s archipelago, and died in Gothenburg in 1984.

Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation No 2, Funeral March (1908)

Around 1908, Wassily Kandinsky’s paintings begin to show his gradual transition towards abstraction. In ”Improvisation No 2., Funeral March”, the figurative elements have not yet entirely disappeared. From the left of the picture frame comes a rider on a white horse with a long, bent neck. On the right, four other figures can be seen. The atmosphere is almost sacred. In his manifesto from 1912, ”On the Spiritual in Art”, Kandinsky explained that what interested him was a style of painting that lacked figurative motifs. He did not, however, strive for pure abstraction – the spiritual content should be highly palpable.

The Expressionists – and Wassily Kandinsky is considered one of its most prominent members –asserted the intrinsic expressive potential of colour. An intense red or a powerful tone of blue can in itself conjure feelings and reactions in the viewer, regardless what the red or blue depicts. In this case, the subtitle of the painting – ”Funeral March” – evokes the tones of an emotionally charged piece of music performed on a solemn, serious occasion, perhaps a funeral. For Kandinsky every shade of colour had the ability to evoke a special musical tone. Colour becomes music, and music colour.

Horses and riders were recurring themes in the work of Kandinsky, as well as fellow artist Franz Marc. They were perhaps taken with the power of riders or crusaders, who had historically laid the world at their feet. They probably saw themselves as the messengers of a new spiritual era. In 1911 in Munich, Kandinsky, Marc and a number of fellow artists formed the group Der Blaue Reiter – The Blue Rider.

Wassily Kandinsky was born in 1866 in Moscow in what was then the Russian Empire. He died in 1944 in Neuilly-sur-Seine in France.