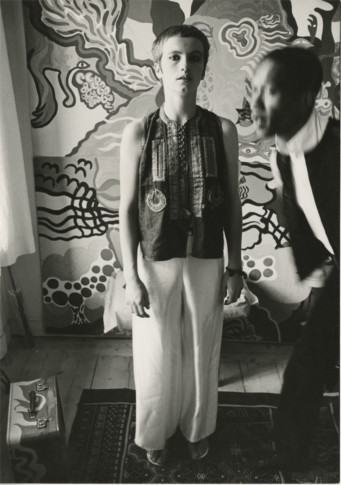

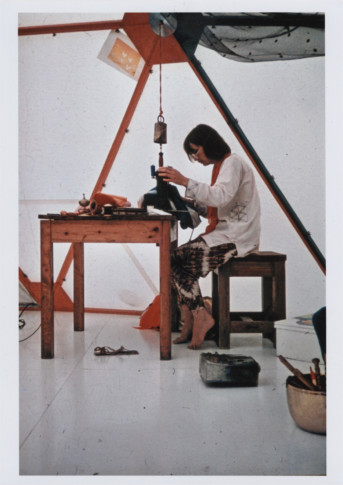

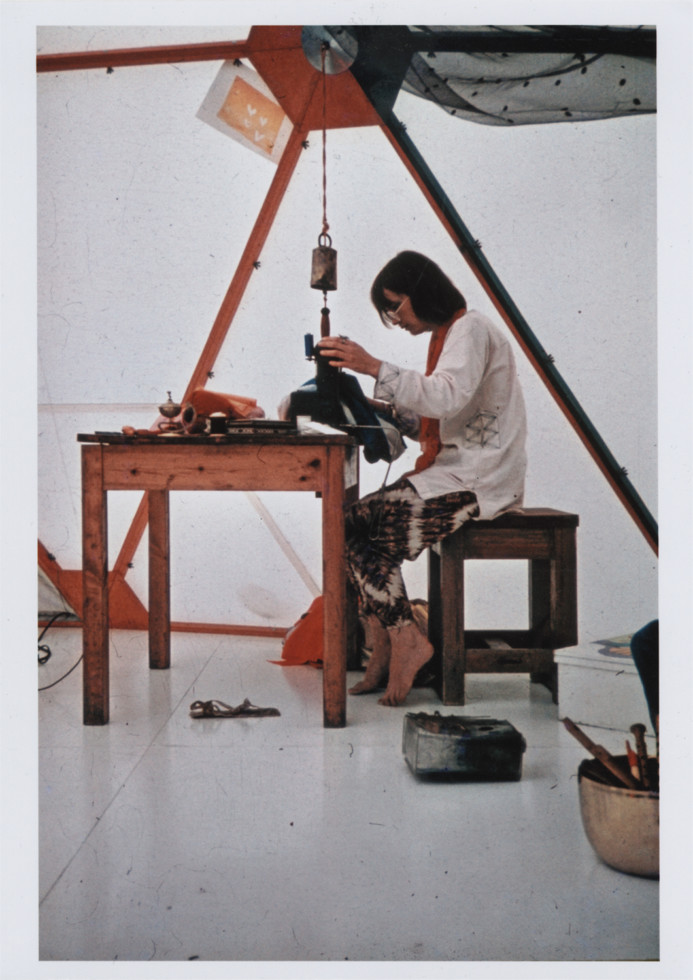

Moki Cherry, Moki working at her sewing machine, Utopias and Visions, Moderna Museet, 1971 ©Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry Bildupphovsrätt 2023

A Journey Eternal

Women’s rights were raging in the 1960s, work life awaited but the prevailing gender roles still meant that women were expected to take care of households and children. Moki employed and creatively subverted these traditional divisions in her art.

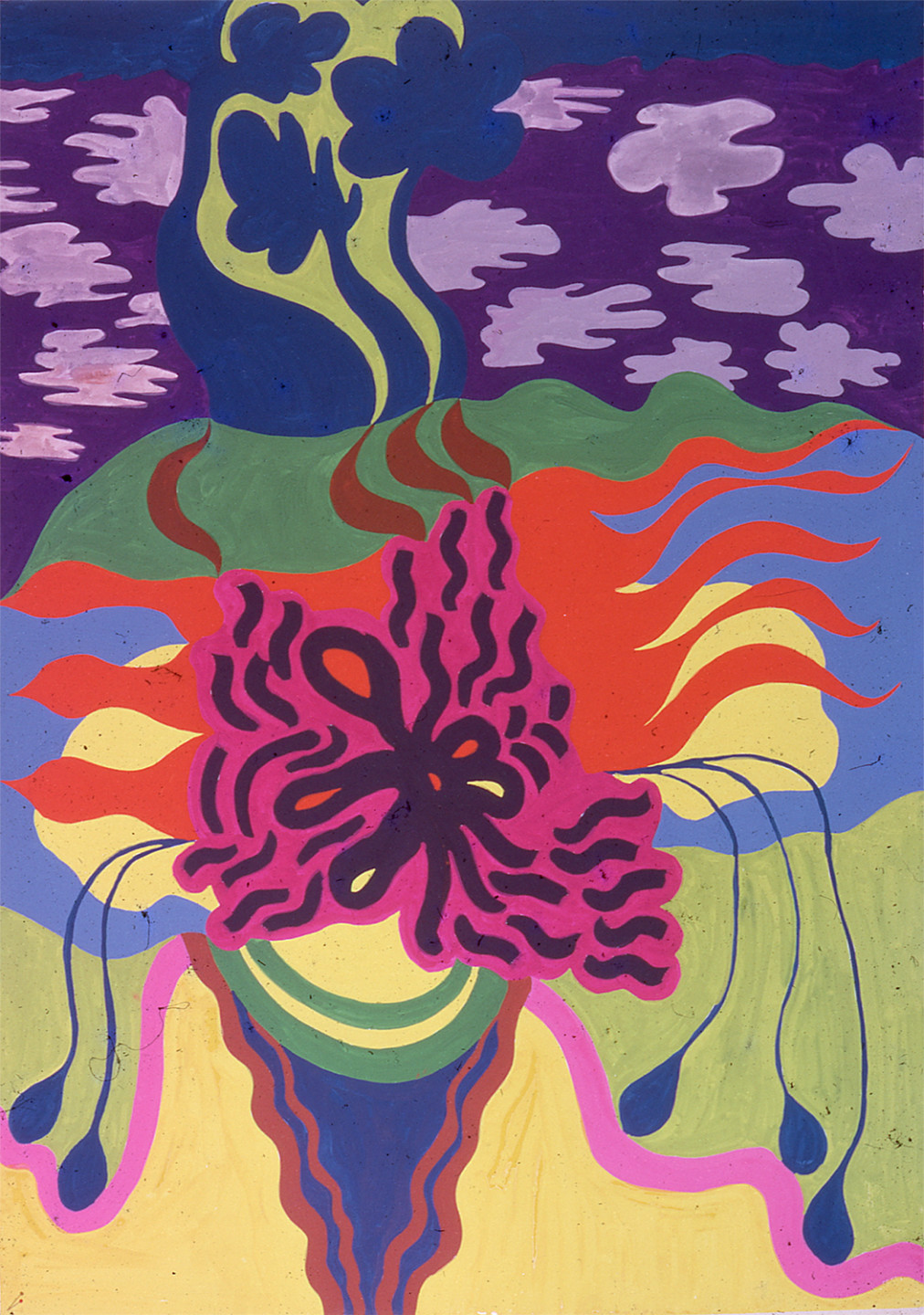

Moki Cherry was a practicing Buddhist for much of the 1970s, and Buddhist philosophy was a life-long influence on her. Her work was influenced by art and cultural history as well as spiritual movements from both Western and Eastern traditions. Obvious inspiration are seen in the textile Chenrezig: Buddha of Compassion (1974), as well as in the sculptural work Buddha (1998). Moki was fond of the potential inherent in starting with a motif that numerous artists had used before her, and would use after her as well, thereby challenging the value of uniqueness and instead seeing the magnificence of her picture being one of many. The result is a multi layered idiom with Naïvist characteristics and symbols, inhabited by human and nonhuman creatures. Later works exhibit traces of Cubism and more abstract forms.

I survived by taking a creative attitude to daily life and chores. (Moki Cherry)

Creative Workshop

The exhibition at Moderna Museet Malmö presents a broad picture of Moki’s art and stretches from the late 1960s to the artist’s death in 2009. In the middle of the exhibition is a creative workshop that also presents album covers, work with children, and TV and radio programs that Moki Cherry was involved in creating. Along with the exhibition of her artwork, her multifaceted production emerges.

ALBUM COVERS AS ART

Moki Cherry’s art filled many functions – as scenography, clothing, pedagogical material, posters, and as album covers. This exhibition displays the album covers that were designed for Don Cherry’s albums. The originals of these covers are often artworks in their own right, which is also seen through a few examples included in the exhibition. The first album cover Moki created for Don is Where is Brooklyn (1966/1969). It is a lively painting with a lot of activity – music notes are flying, a train comes in from the left, a green person in a black cape stretches out their arms and legs as if dancing, flames seem to flicker up in the lower left corner.

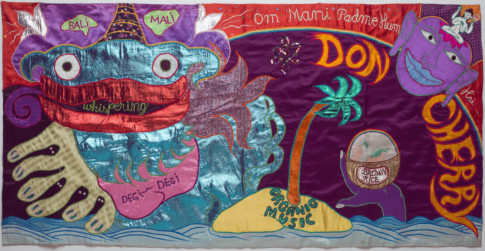

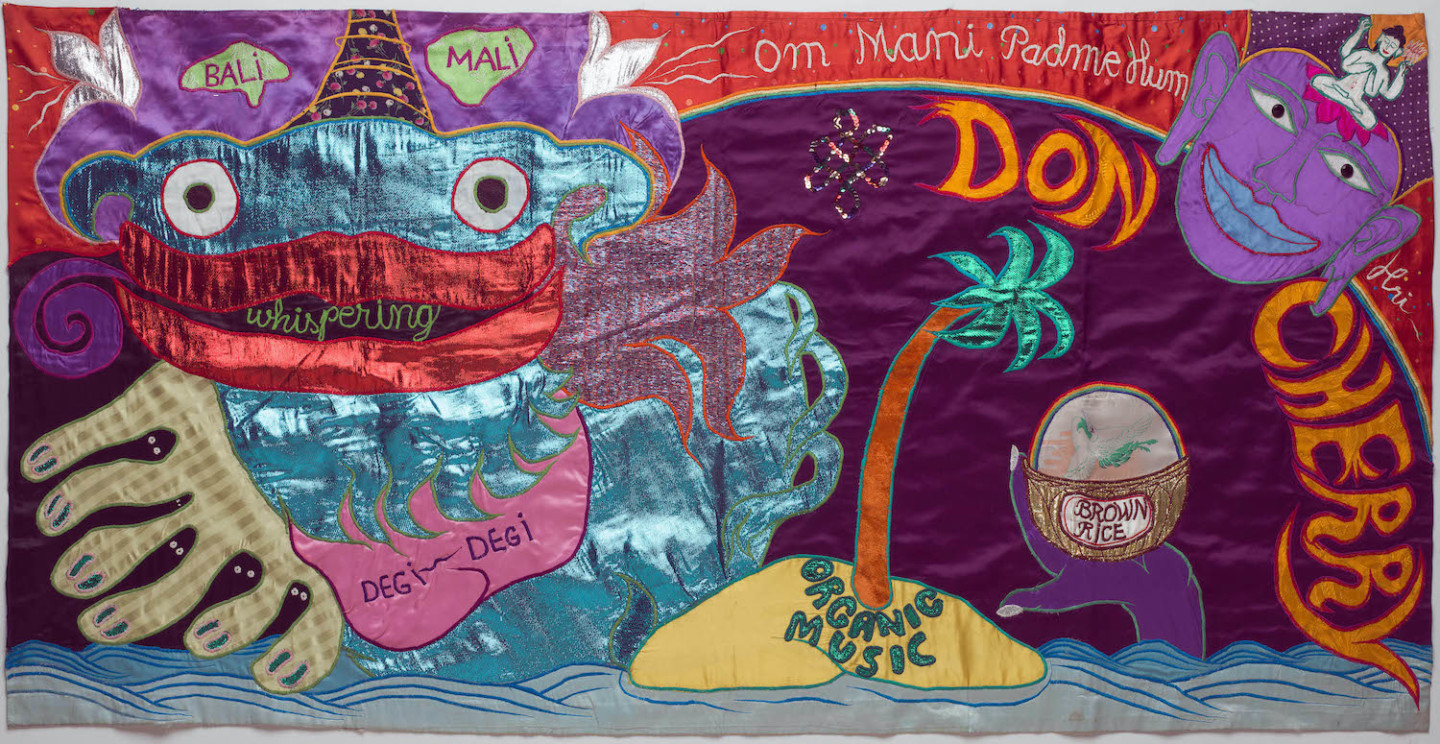

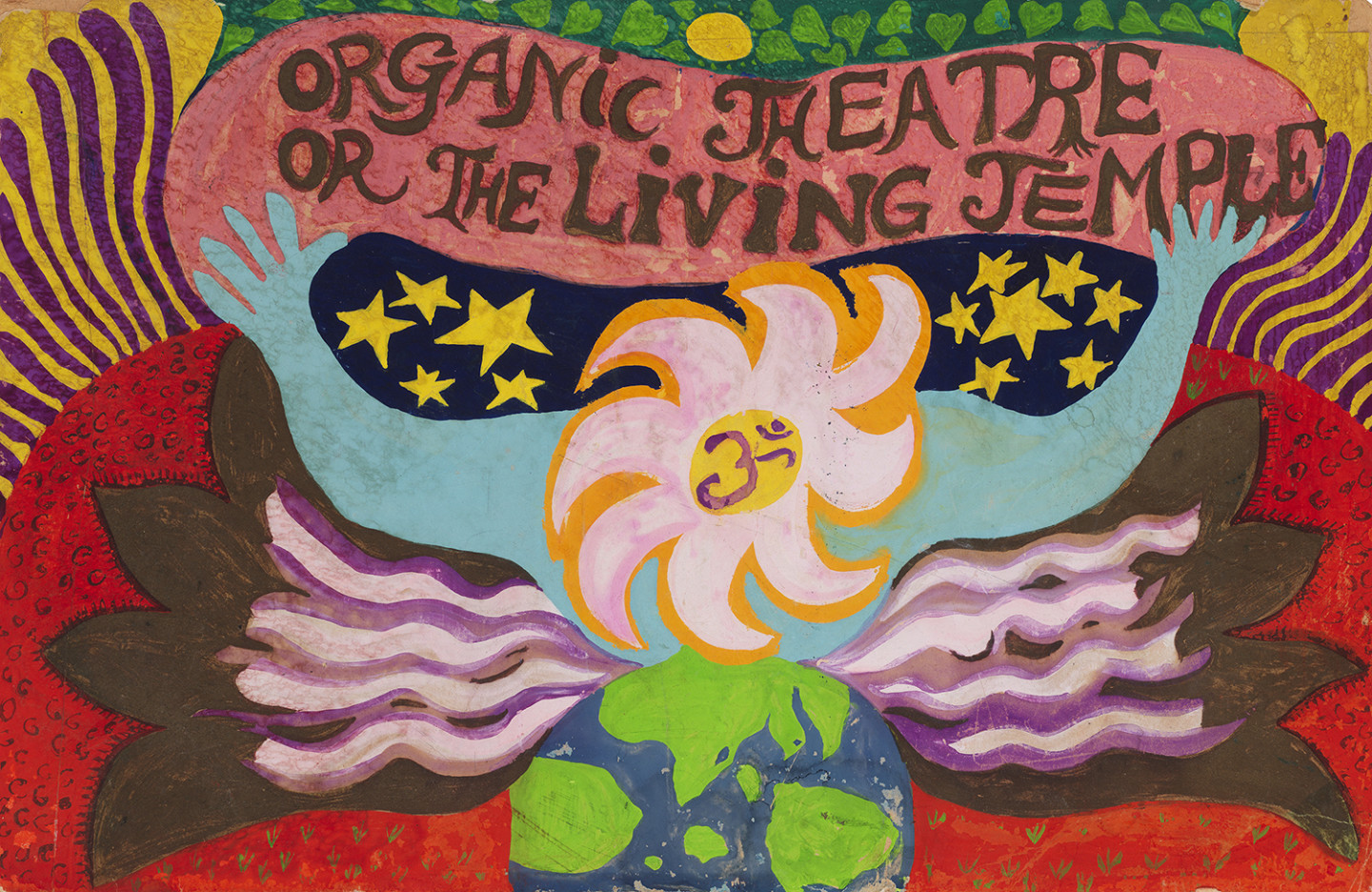

A somewhat calmer cover and textile piece that shows Moki and Don’s ambition to live more health fully is Brown Rice (1975). The album contains several song titles that refer to vegetarian dishes and crops. On the cover of Organic Music (1973), whose ori ginal painting is also seen in the exhibition, we see the building, the dome, that was placed outside Moderna Museet in Stockholm in connection with the exhibition Utopias and Visions 1971-1981. The record includes music recorded at Moderna Museet, and the inside of the gatefold cover has a collage with photographic documentation from the same exhibition.

FUSING LIFE, ART AND MUSIC

Together, Moki and Don Cherry established Movement Incorporated (1967), which later became Organic Music Theatre, sometimes referred to only as “Organic Music”, (1971–1976). It was a way of uniting art, music, and life and to create a protective, all-encompassing environment centered in their various homes: first in various places in the USA and Europe, and from 1971, in Tågarp in Skåne.

Musicians and other creative people from all over the world came to their house in Tågarp to study or prepare for tours. Moki Cherry described it as an Open House feel. In 1971, Moderna Museet’s then-director Pontus Hultén invited the Cherrys to contribute to the exhibition Utopias and Visions 1871–1981. Moki’s close friend, artist Tonie Roos, was also involved in the organization. This was the first time the Cherrys were able to create an entire encapsulated environment at an art institution. Over 72 days, they worked in a geodesic dome designed by the Swedish artist and designer Bengt Carling, based on the ideas of the American architect Buckminster Fuller, placed at Skeppsholmen in Stockholm. Here, Moki displayed textile works that hung from the ceiling and along the walls and painted gradually day by day a mandala that covered the floor. Moki sewed and made new artworks every day, and the family lived by the museum throughout the exhibition. Visitors could borrow costumes or take a seat on soft sculptures. Everything was part of an informal meeting place where visitors found spontaneous concerts being performed or other activities that they could take part in, and the project was in continuous transformation.

The current exhibition title “A Journey Eternal” is taken from the publication that was issued in connection with Utopias and Visions 1871–1981. These are the last words in a meandering text by Moki and show her holistic worldview that permeated both art and life and where fantasy and reality coexist. When Organic Music Theatre was established, Moki wrote enthusiastically in a letter, “This is the biggest thing to happen since the Russian Ballet” (1909–1929). It is a comparison that underscores how the historical predecessor transformed performing arts through its genre-crossing collaborations with the foremost artists and composers of its time, as did its later counterpart, the Swedish Ballet (1920–1925).

A concert at Charlottenborg with music by Don and sets by Moki in Copenhagen in 1967 was presented with the title “Welcome Live-in,” and a letter from the same year includes billowing text proclaiming “Don & Moqui, Movement Inc.” A later parallel to the couple’s all-encompassing artwork and life as art is John and Yoko. It was in 1969 that John Lennon and Yoko Ono tucked themselves in for a “Bed in” and invited international media into their bedroom.

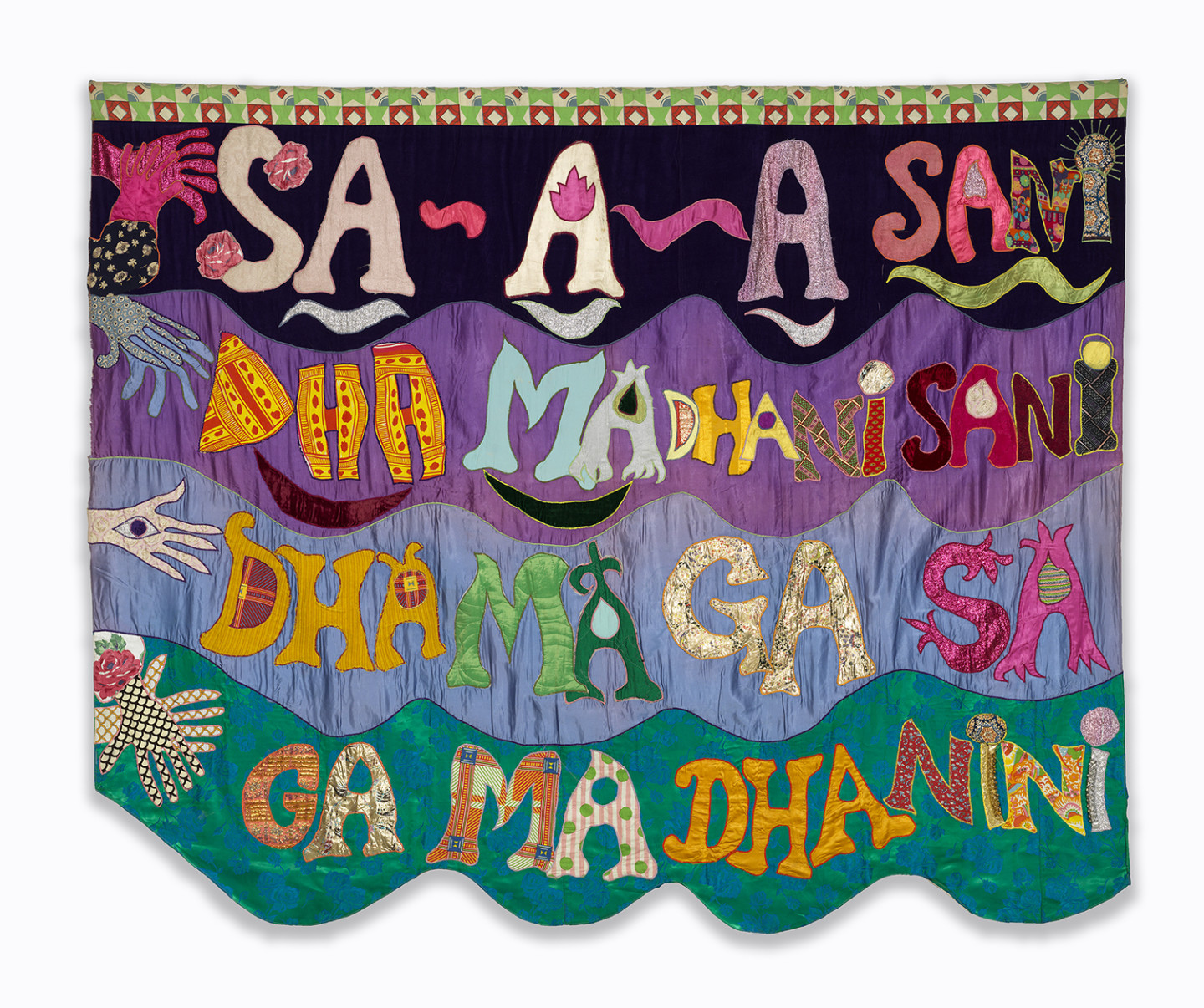

Mobile works

Several of the works in the exhibition at Moderna Museet Malmö, among them Malkauns Raga (1973), Dina Kanagina (1972) and Aum Expression (1971), were used as scenography for concerts such as the Newport Jazz Festival, 1973. In the documentation from a concert at Moderna Museet in Stockholm 1977, the large textile Dragon (1975) can be seen. As mobile works, these, along with other pieces in the exhibition, could be placed in various contexts based on improvisation in the moment–concerts, exhibitions, workshops. Moki Cherry’s work seems both exclusive and collective in its form. They organically find their place. The group’s association was also fluid; in 1973, several joined Organic Music, among them musicians Christer Bothén, Naná Vasconcelos and Bengt Berger, as well as artist Annie Hedvard.

CLOTHING (AND LIFE) AS ART

Moki Cherry’s artistic path begins in the 1960s in fashion. When she was 16 years old, she left home to work at the women’s outfitters Modellen in Kristianstad and later in the same city at the women’s coatmaker Distingo. In 1962, she left Skåne to study at Tillskärarakademin in Stockholm and later at Anders Beckman’s School. After finishing school, Moki sold a few unique garments in New York at the trendsetting department store chain Design Research D/R and the luxury fashion department store Henri Bendel. But Moki Cherry abandoned her ambitions in the field of fashion and instead further developed her artistic endeavors. She continued making clothes, however; her own, her children’s, Don’s, and his bandmates’ for stage performances. It was an economic necessity and an artistic opportunity.

Before an appearance in 1966, she styled Don Cherry and his quintet in completely white clothing, and the concert was immortalized in an early music video, an “electronic painting” that was broad cast on Swedish public television: Time by Ture Sjölander and Bror Wikström. Today, the memory of the stage performances is closely associated with how the environments and the people looked. The way they are dressed is a central element of how the full picture of the music was formed and lives on today. The clothes are playful and have genderbending designs with the softness of the material allowing movement. The boundary between painting and textile applications is fluid, and the applications and the clothes have the same expression, they are an integrated part of Moki’s art. Moki Cherry’s motto was Life is my artwork in that mode a cupboard could also be a collage and an instrument case a painting.

THE ART FROM THE 1980S AND ONWARDS – ABSTRACTION, COLLAGES, AND OBJECTS

In her art, Moki Cherry was an inquisitive researcher. She experimented with materials like plywood and clay, then returning to or working in tandem with textile applications, collage, and painting. The stylized representational and playful motifs from the 1960s and 1970s gain a new expression in the 1990s in paintings with acrylic on panels or cardboard, a practice that continued for the rest of her life. Angular forms become labyrinthine landscapes with spacelike creatures and in abstract works, the forms are brought together in compositions with bold colour combinations. Several of the abstract paintings are designed as diptychs, with one picture picking up where the other ends. Sometimes, a representational element appears, gear wheels and veins lead the thoughts toward mechanics as well as bodies.

In her notes, Moki Cherry writes about how she begins working with bow saws in the 1970s, abandons it, but takes it up again with new, better tools in the 1980s. She saws out peaceful figures such as Buddha (1998) or expressive faces in plywood and constructs sculptural, wall-mounted lamps. At Greenwich House Pottery in New York in the 1990s, she begins creating ceramics. She makes dogs and winged goats, some with bodies shaped as dishes and utilitarian objects. Along her vases and across bowls, snakes entwine, a motif she constantly returned to and where the snake biting its own tail symbolizes eternal cycles and for Moki it was a way to depict time. She gained inspiration from ancient ceramic traditions and many other cultures, but it is also possible to see a kinship with contemporary art colleagues such as her friend Niki de Saint Phalle and Ulrica Hydman Vallien’s 1960s ceramics.

In the 2000s in New York, Moki Cherry immersed herself in creative writing for the feminist art historian Arlene Raven. Regardless of whether it was a sentence on a bowl or a longer poem, writing was always an active part of her artistic practice. In the home, Moki covered furniture – desks, chairs, and bookshelves – with newspaper photos and created three-dimensional collages that became a part of the decor. From 2003 on, she dedicated herself to two-dimensional collage – more austere, sensual with surrealist combinations, as in Let it Flow (2006), which combines oysters, orchids, twisted forms and folded fabrics. By bringing together pictures she had collected, she continued in her characteristic way to blend the personal and the political, humor and war, and women’s rights and fantasy. In 2007, she wrote: “On my second birthday, my mother gave me a very sharp pair of scissors. It’s interesting to arrive at something so familiar – scissors and paper – after a lot of life and experience. It might look back at you.”

FANTASY AND EXPERIMENTAL CREATION WITH CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE

In the exhibition, there is a creative workshop which is a natural extension of the self-evident inclusion of children in the creative context created in Tågarp and other projects. In the 1970s, new art was asking for a new society. The boundary between private and public was fluid, and at concerts, hierarchies between musicians and audience were dissolved, and viewers became participants. Between 1978 and 1986, for nine summers, Moki Cherry and Anita Roney were central for the children’s theater Octopuss’ performances. They made costumes, scenography and organization for the teenagers’ self-written and self-directed performances, which were created over five to six weeks. The premiere took place in Tågarp and then they toured and often finished at Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

The 1970s in Sweden are associated with original and experimental children’s programs, which was partly a result of Swedish Television had created a children’s program board in 1969; children’s programming thus had status. In 1971 the children’s program Piff, Paff, Puff was recorded in Tågarp (broadcast in 1972), and in the same year, Elefantasi with the main character Fantasimon was created for Swedish Radio with the Cherrys. Loosely connected, the programs encourage creativity – play, music, and stories create the action, and the children participate.

Playfulness and inclusion

Moki and Don Cherry and others connected to Organic Music arranged almost 90 school workshops in 1973 under the direction of the Swedish Royal Concert agency and toured the length of Sweden. Participants dressed in colourful clothes, and children and young people played and sang along with lyrics that were depicted on Moki’s textiles. The schools they visited received pedagogical materials in advance so they could prepare.

After having exhibited in the geodesic dome outside Moderna Museet in Stockholm, former museum director Pontus Hultén again invited Moki and Don Cherry, this time to work in a capacity specifically focused on children at his new workplace, the Centre Pompidou in Paris. In 1974, Atelier des Enfants, the children’s workshop, introduced the endeavor before the new museum building was finished. In the exhibition’s workshop at Moderna Museet Malmö, the playful and inclusive attitude is taken further.

Text: Curators Elisabeth Millqvist and Andreas Nilsson