Moki Cherry, Installation view, 2023 Photo: Helene Toresdotter/Moderna Museet Bildupphovsrätt 2023

Mobile Aesthetic Environments

Moki Cherry was an interdisciplinary artist who over her lifetime made paintings, drawings, textile appliqué tapestries, fabric sculptures, ceramics, costumes, wood sculptures and photomontage collages. She collaborated in life and love with her creative partner and husband American jazz trumpeter, Don Cherry, whom she met going to jazz clubs as a student in Stockholm. Sharing a life creatively and in the home, Moki and Don’s aesthetics interwove and they were each other’s muse – Moki’s output was widely considered as the ‘visual embodiment’[1] of his music.

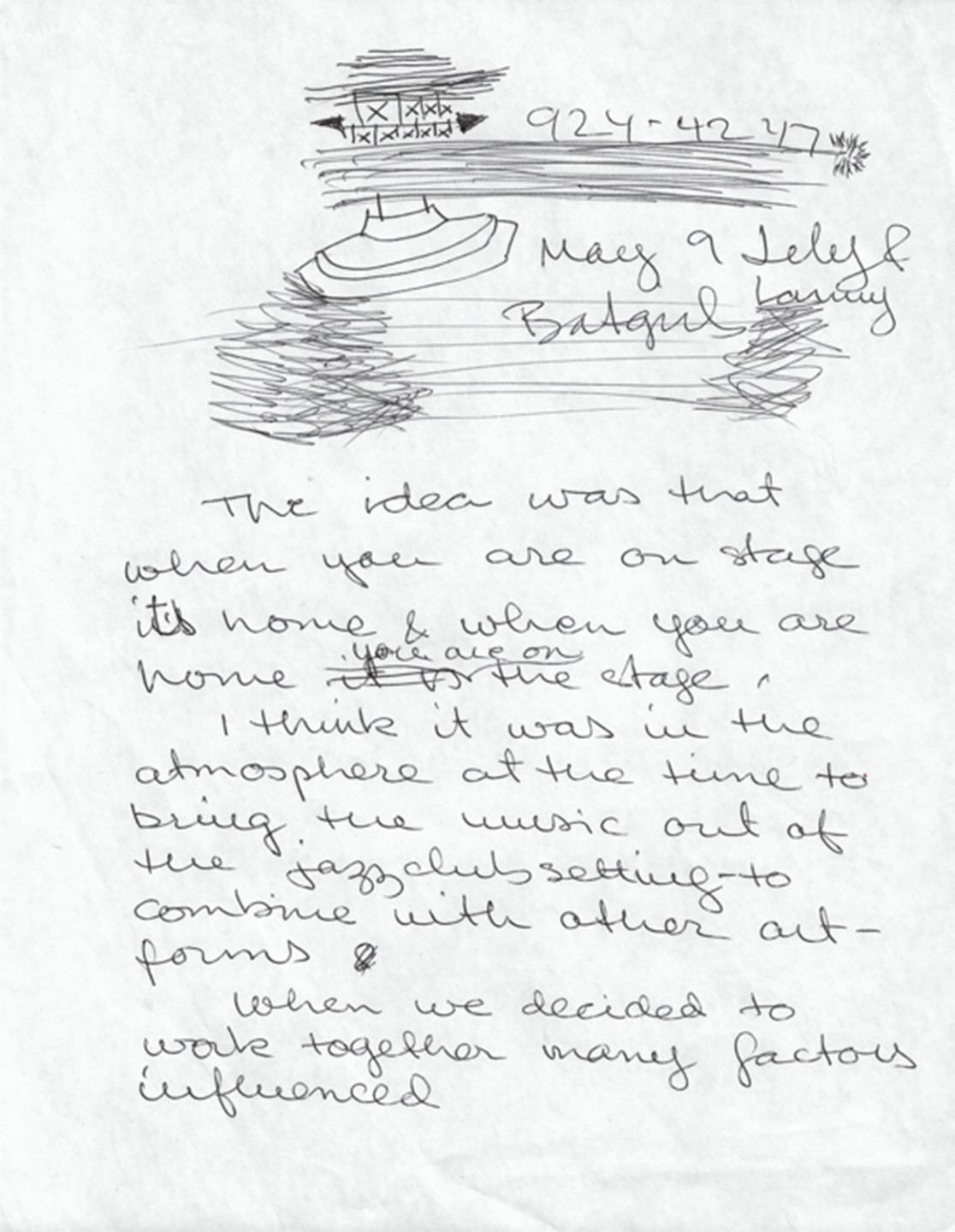

During the sixties and seventies they travelled incessantly with their children putting on concerts and work-shops. Moki transformed the spaces in which these transient events took place with large tapes-tries, fabric sculptures and costumes experienced together as mobile aesthetic environments. She searched for possibilities to extend and connect values in the home, as a mother and wife, with her output as an artist constantly on the move and uncertain of what she would do or where she would go next. Moki not only produced and shared her work for public audiences but she also fed an expanded collaborative creative vision back into the home, dissolving boundaries between the domestic space and the stage. Moki captured this approach in a note: ‘when you are on stage its home, and when you are home you are on stage’ (fig. 1). Her immersive bold visuals brought consistency amid the itinerancy and she transformed spaces in a mobile creative practice she could carry with her.

Monika Karlsson was born in Koler, Norrbotten, Sweden on 8th February 1943. Her parents, Ma-rianne and Werner, were from opposite ends of the country – her mother, Norrland in the north, and her father, Skåne in the south. Moki’s younger brother Christer remembers how Moki was independent from early on and it was as a teenager that her friends started calling her Mocki[2]. The family often relocated as her father was a railroad employee so they moved around Sweden to where he got stationed. In Moki’s reflective writings, she fondly recalls ‘going up and down the country like yo-yo’s’[3] with her family. From this early age, then, travelling and transience were part of Moki’s life, which was echoed in her lifestyle touring with Don and their children, Neneh and Eagle-Eye, of later years.

Moki left school in 1959 to apprentice at the Haute Couture Atelier, Anna-Greta Blom and went on to work in ready-to-wear as a design assistant with Vera Öhrn at Distingo, a women’s coat and suit manufacturer in Kristianstad. In 1962, with the intention of putting herself in good stead to become a fashion designer, she moved to Stockholm for evening classes in pattern-cutting and drapery at Stockholms Tillskärarakademi (‘Stockholm’s Cutting Academy’) before studying fashion design, illustration and pattern-cutting at Beckmans Designhögskola (‘Beckmans Designschool’). It was at this time that she started signing her name as Mocqui or Moki and began to think of herself more as an artist-designer, while developing her skillset that would later be ap-plied to her brightly coloured creations of years to come. Mid-way through her studies in 1964, Moki gave birth to her first child, Neneh, and even when balancing studies with being a new mother, she was recognised as ‘an original and imaginative pupil’[4]. Already Moki was extending ideas of home in her unique way and sometimes brought baby Neneh to Beckmans with her.

Communicate, how?

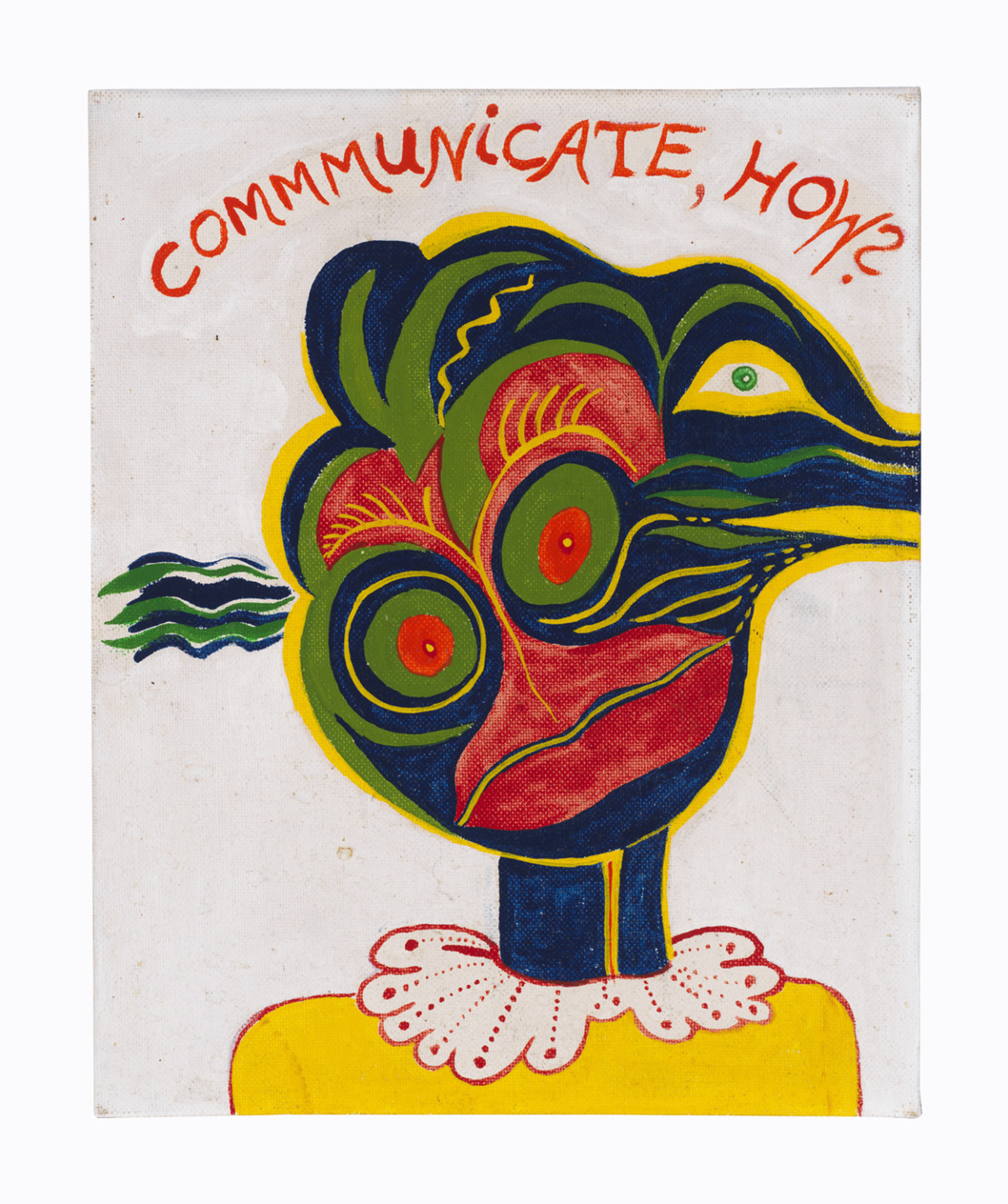

Communicate, How?, a small canvas painting from 1970, depicts this question in Moki’s stylised hand arching over a blue chimera dressed in a collared blouse (fig. 2). Her feminine face is made of supernatural streams of interlinking roots, leaves, a floating third eye and a puff of waves se-cretes from her head. The question framing this fantastical portrait indicates the importance of communication for Moki, of sharing what Vivien Goldman, journalist and friend, described as her ‘colourful, sensuous world view.’[5] The extending of natural into supernatural forms meeting inside a feminine subject signals Moki’s search for possibilities of expanding and warping traditional fixed formats of femininity and communication.’[6] This questioning and stretching of boundaries and forms is at the root of Moki’s work.

In the sixties and seventies Moki and Don went from place to place to wherever they could get work for performances – inevitably mobility affected the form of Moki’s work and what she made needed to be transportable. In 1969, she wrote in her diary about a long journey from New York through Iceland, Luxembourg, Cologne and Amsterdam to get to Copenhagen:

‘I shoved some of my paintings into sacks half-full with fabrics, and pushed everything – the typewriter and instruments – into stacks up on the pushchair.’[7]

Having children, little money, and transporting both her and Don’s musical and artistic materials together were circumstances Moki worked within and through in order to communicate, and so she asks: ‘Communicate, How?’ These conditions, and this question, inextricably impacted the art she made.

Moki’s visual work began to combine with Don’s music when she styled Don’s band, Together-ness, dressing them in white cook’s jackets and trousers for a concert at The Golden Circle, Stockholm in 1965.[8] The next year this styling expanded into making posters and a blue suit for Don, specifically for Elefantasy, a concert they produced together at Town Hall in New York. This was also when Moki’s vision started to extend onto the cover artwork for Don’s albums with a drawing featured on Where is Brooklyn? (Blue Note).[9] By 1967 Moki and Don’s collaboration had a name: Movement Incorporated.

Moki’s focus in fashion design and pattern-cutting evolved when social factors led to her exploring different art forms. In 1966, Moki was in New York with Don, selling her one-of-a-kind garments at Design Research and Henry Bendel, but her visa ran out. She returned to Sweden in Autumn, even though the fashion photographer and film-maker, Bert Stern, had just offered to sponsor her as an artist-designer. This opportunity stood for economic independence and stability if only she could get back to the states. While waiting to receive papers to know if she could return, Moki recorded having a ‘kind of visitation’[10] and ‘spiritual experience’[11 ]where she ‘started painting and painting’ .[12] Even after travelling to get Neneh from her parents in North Sweden, and then travelling to join Don in Paris she ‘kept painting’[13].

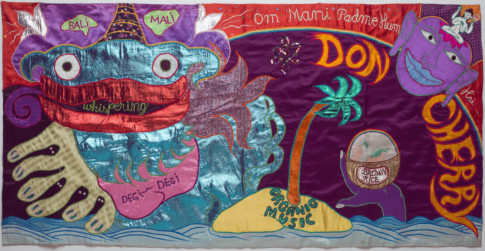

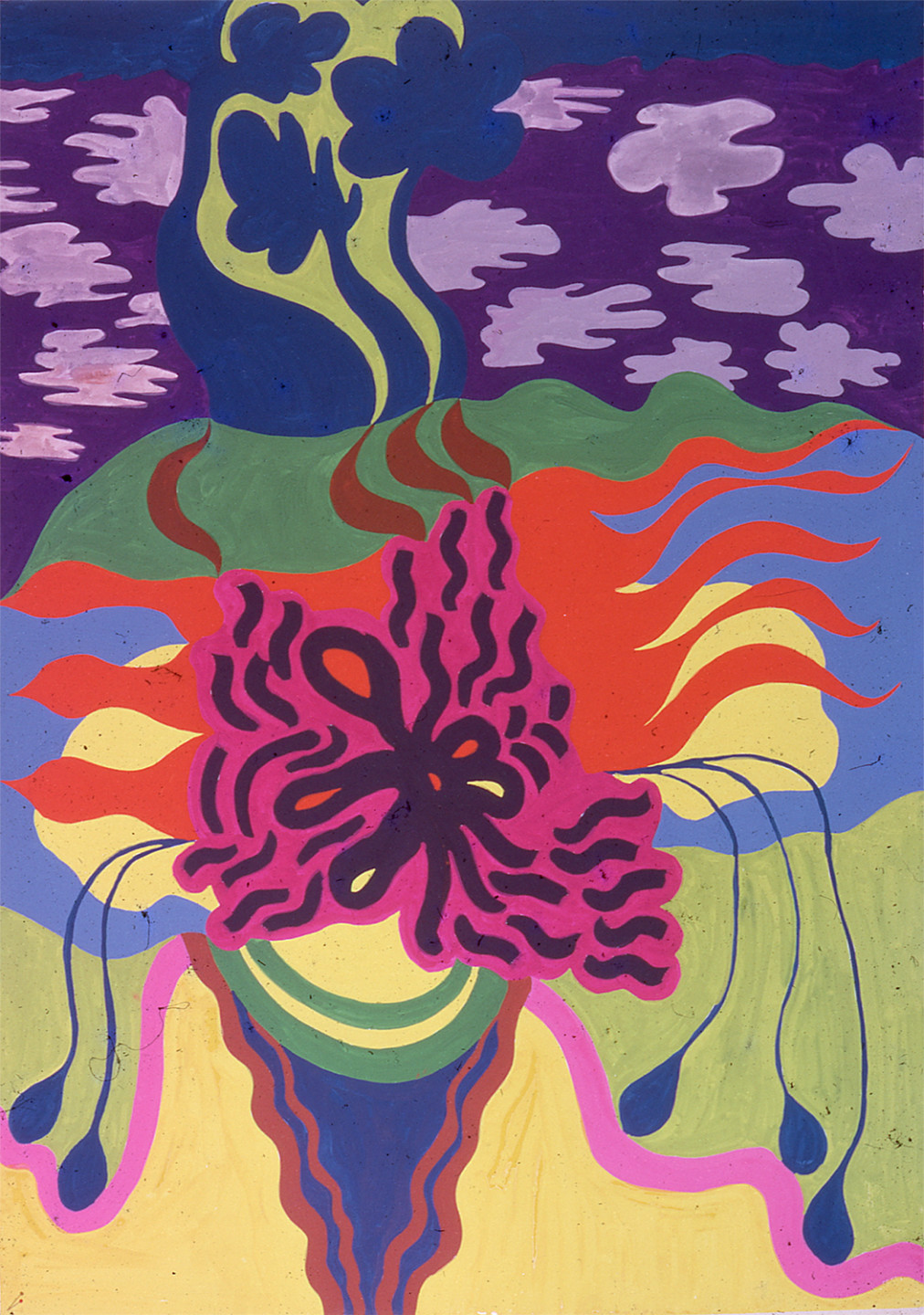

Over the next two years, Moki produced many colourful graphic paintings of blossoming shapes that blend into psychedelic swirls and wriggles with hidden faces (fig. 3). Painting offered Moki an accessible site of expression to explore and extend the possibilities of form when waiting to hear about her uncertain future and living on-the-road with her family. Instead of taking up the job in New York, Moki explored new ways to communicate her art while in an immersive collaboration with Don in the years that followed.

Possibilities

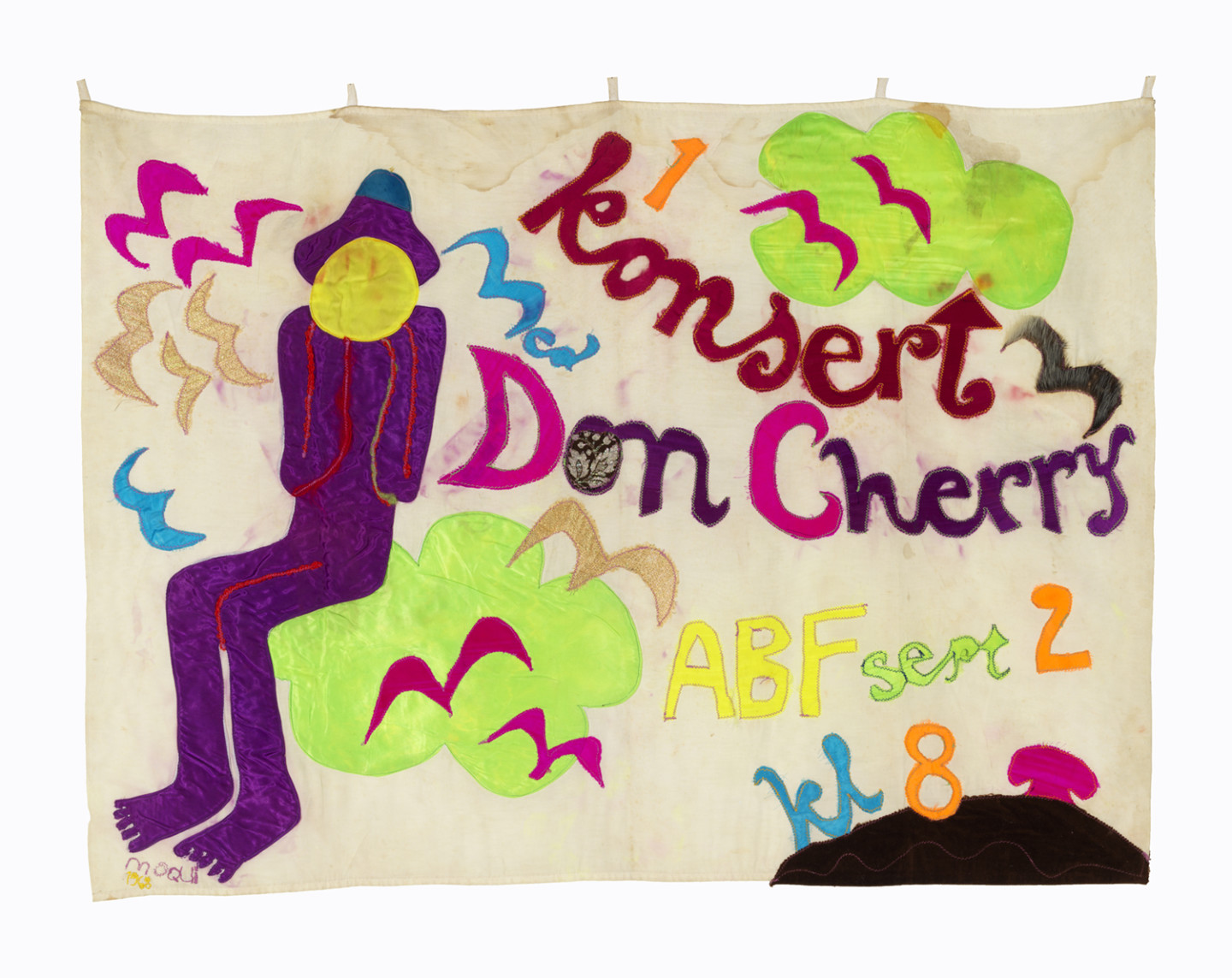

Moki found possibilities to develop a consistent creative practice out of a transient lifestyle of touring, looking for places to put on shows, not having a fixed studio base, and taking care of her family. She took these circumstances and made them into an alternative means of production by making tapestries as the posters for Don’s concerts. An early textile appliqué tapestry-cum-poster (fig. 4) made for a concert in 1968 depicts a slim purple figure as Don with the mouth of his trumpet, a yellow circle, covering his face. He sits on a lime green satin cloud surrounded by birds with logistical information, ‘Konsert med Don Cherry at ABF Huset, Sept 2, Kl 8’[14] (‘Concert with Don Cherry at ABF House, Sept 2, Kl 8’), stitched in multicoloured lettering. In the tapestry the same piece of turquoise satin is a symbol of a bird and the ‘m’ that begins the word ‘med’ (‘with’).

This morphing and extending of visual into written form points out Moki’s fluid approach to her artistic practice. She made an opportunity to make art that warped boundaries of form and definition in its content, as well as of use and context as promotional communication.

Moki wrote reflectively of this time making ‘big tapestries for stage or transformation of room or place’[15] and working ‘visually with Don & the music with visuals and all means to make “home where you are”…on stage, trains, inside/outside, everywhere…’[16]. This emphasis on the transportable and transformative possibilities of her visual work that altered a space became characteristic of her creative practice in mobile aesthetic environments. Also, the name Movement Incorporated literally points out the significance of incorporating movement in her work via this collaboration.

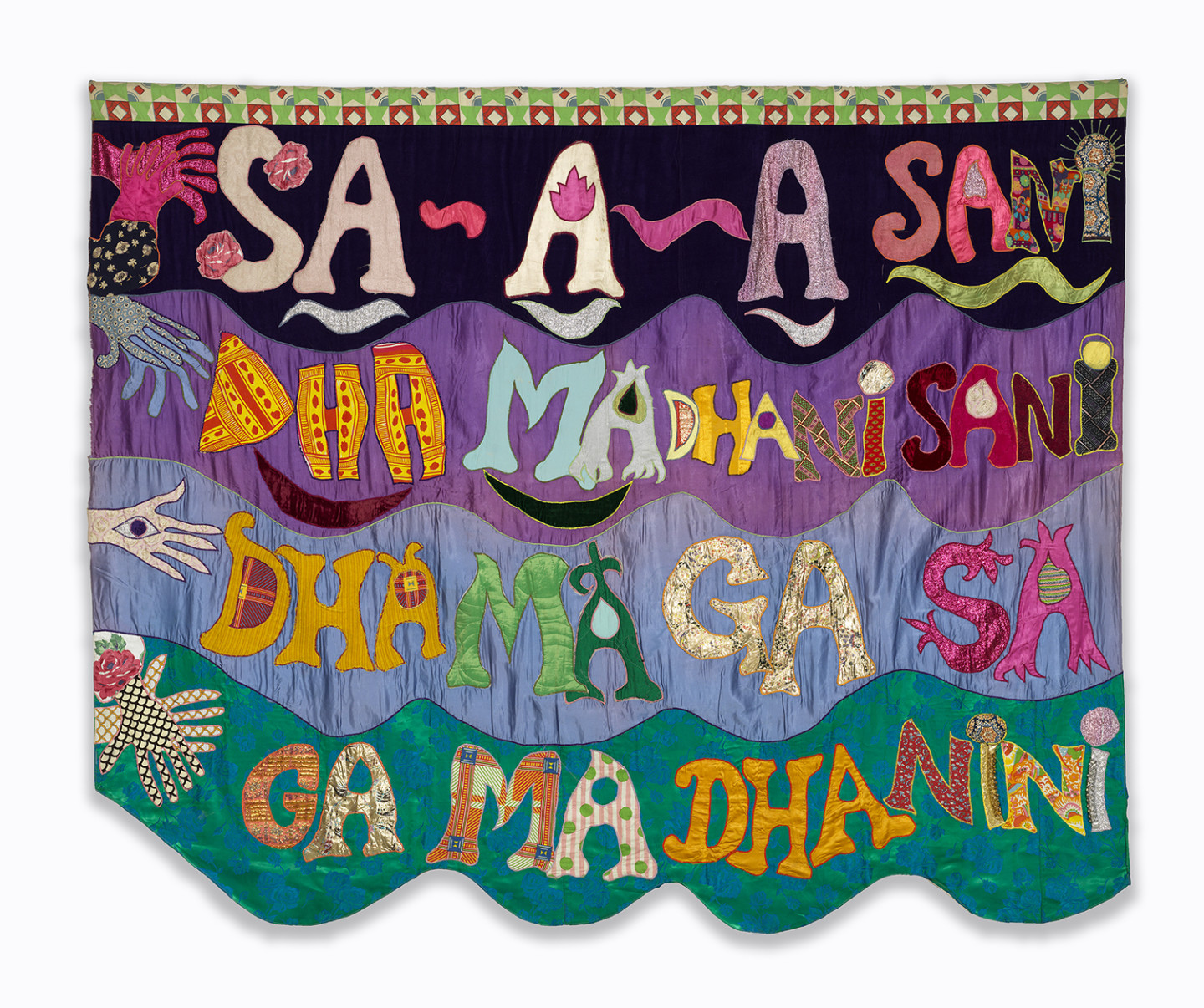

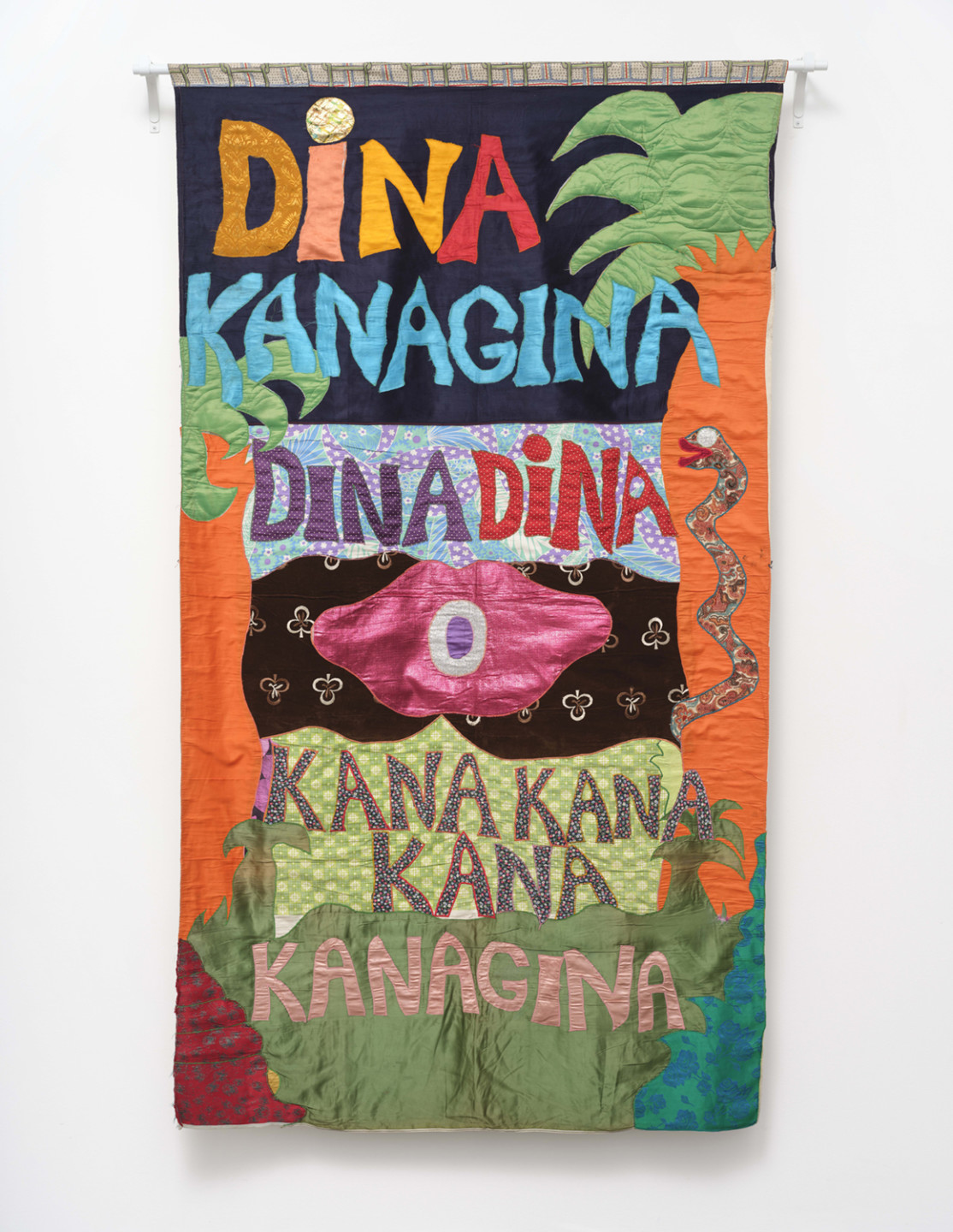

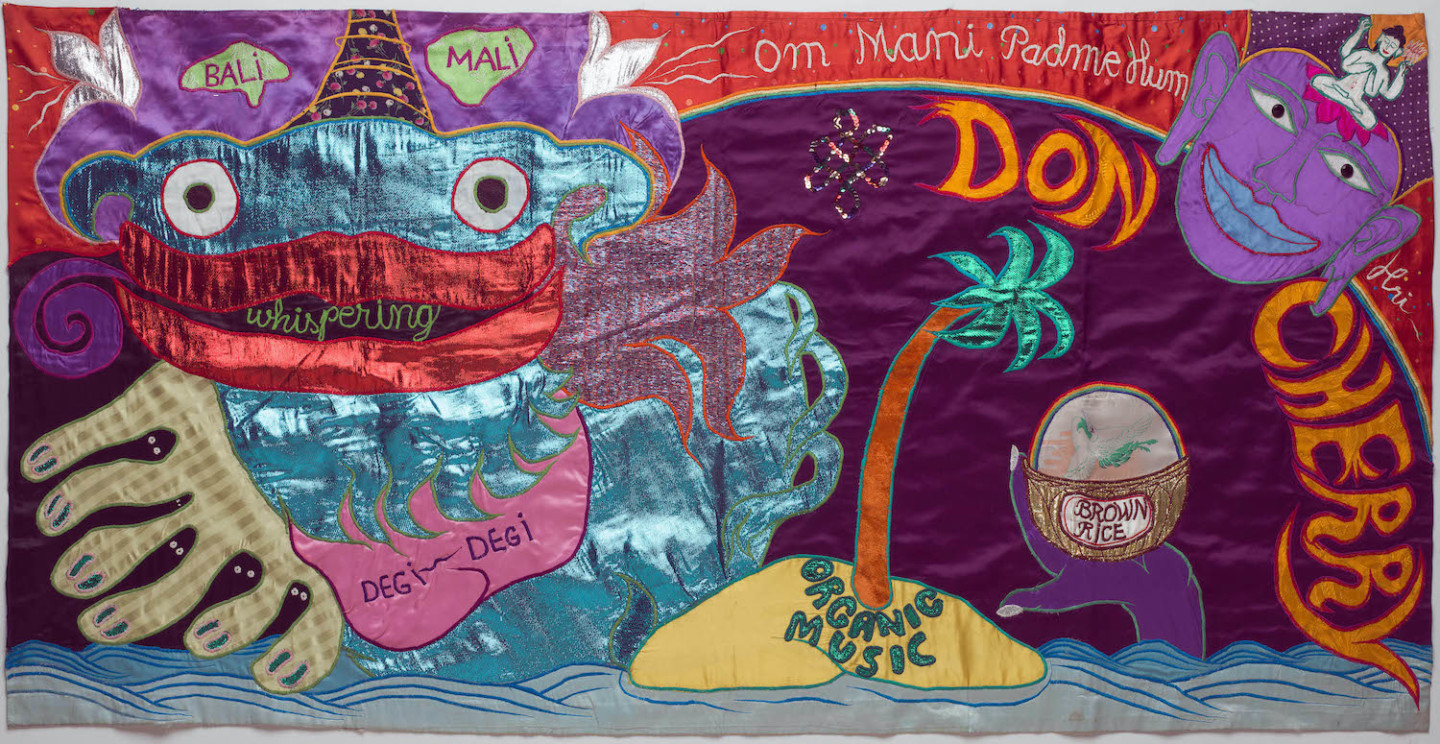

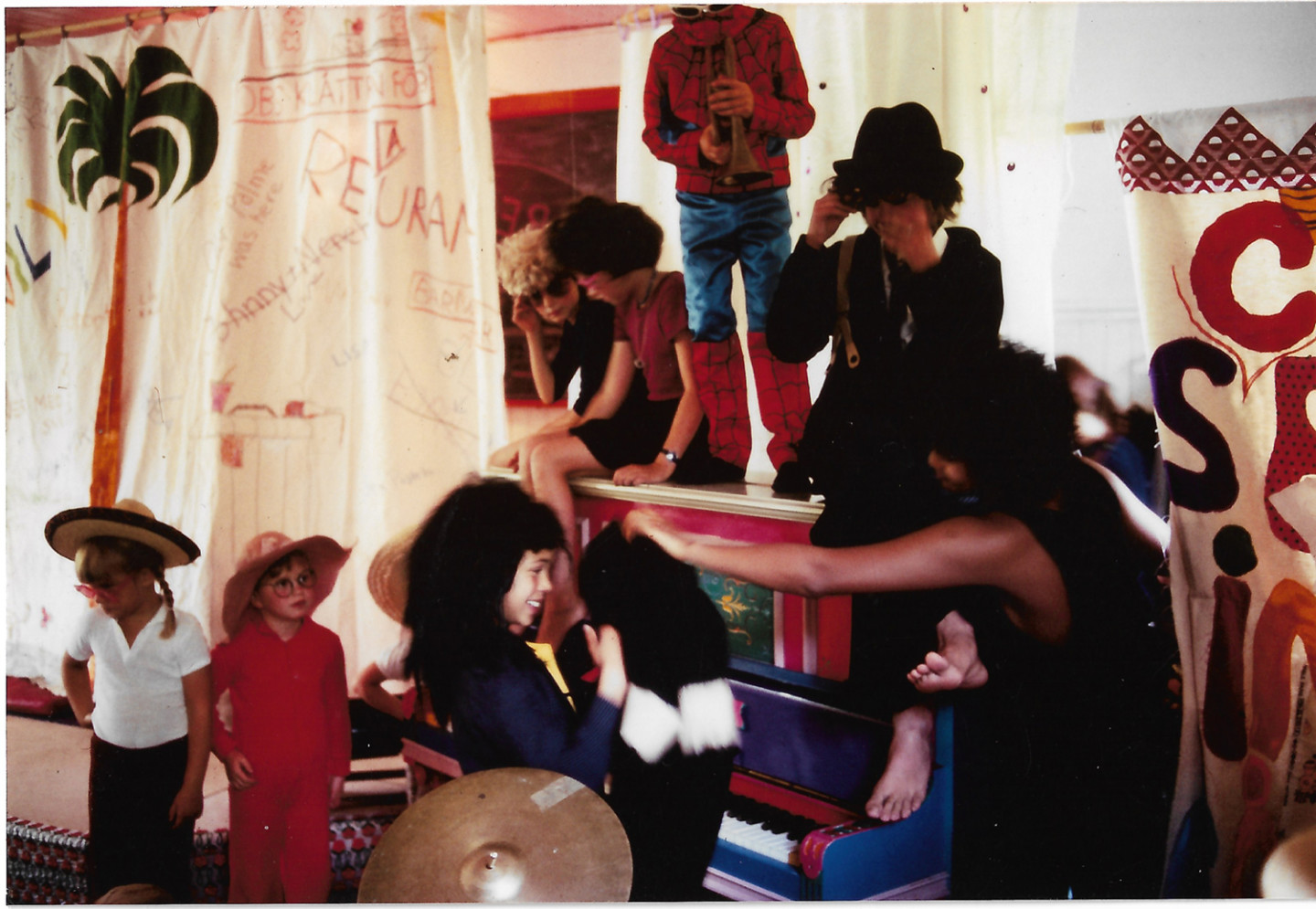

The year Movement Incorporated formed, Moki travelled internationally for concerts in Stockholm and Copenhagen, and she made sets for a performance on the premiere of colour TV in France. Six years later the transformative possibilities of her visual work were still at play when her and Don’s later collaboration, Organic Music, performed at Newport Jazz Festival. Moki’s tapestries, Malkauns Raga (fig. 5), Dina Kana Gina (fig. 6) and Aum Expression (fig. 7), surrounded musicians[17] on the stage and were held up by Moki for the audience to engage with (fig. 8). The vivid tapestries softened the towering grids of metal scaffolding bars in the festival’s stage construction creating an enclosed environment. The same approach was applied to other collaborative endeavours from the early seventies where tapestries were hung in school halls for children’s work-shops they ran (fig. 9) or draped over the ground and hung on instruments on tour in Italy (fig. 10).

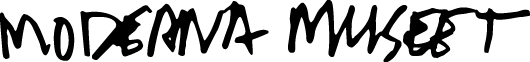

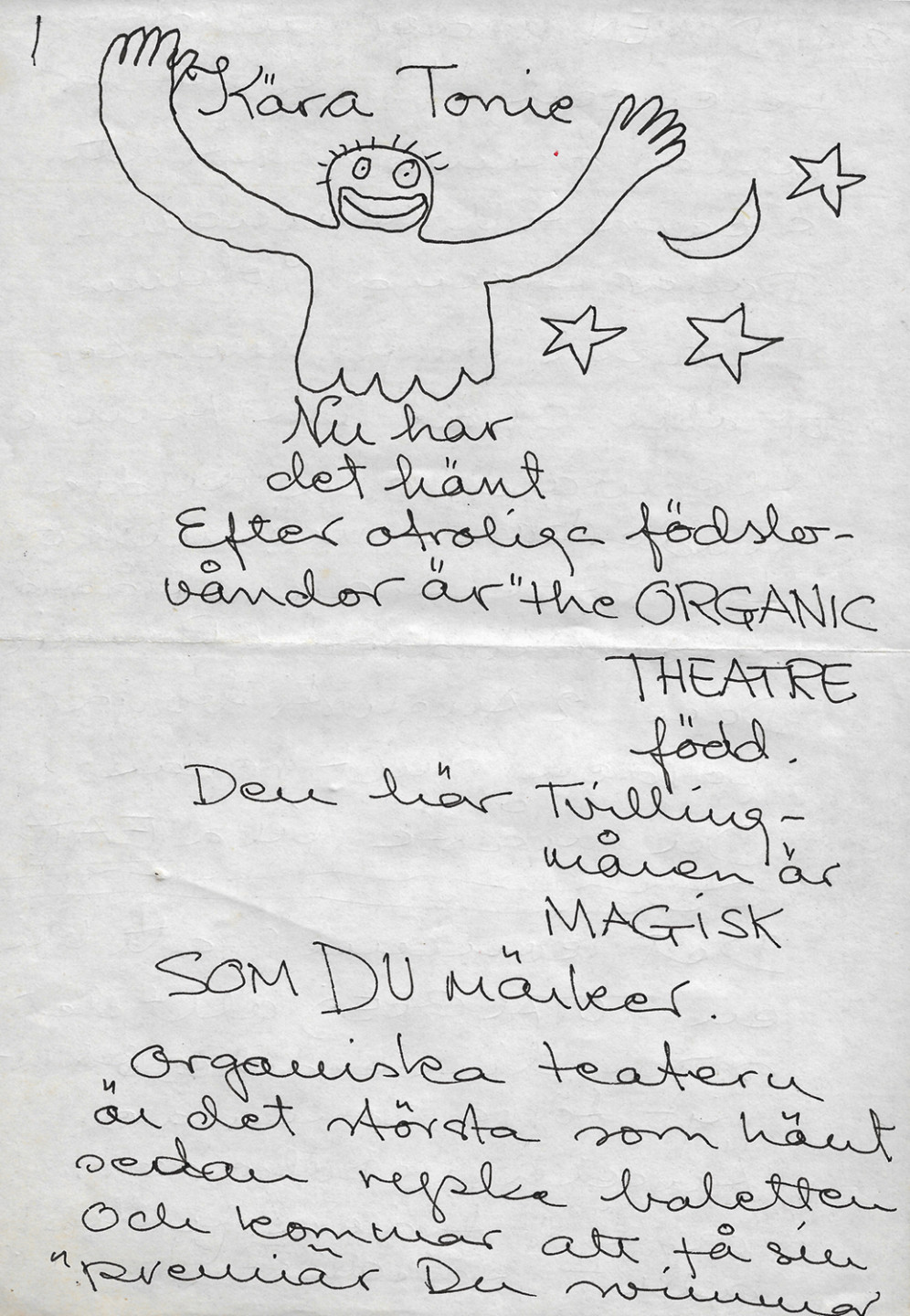

Organic Music Theatre or the Living Temple

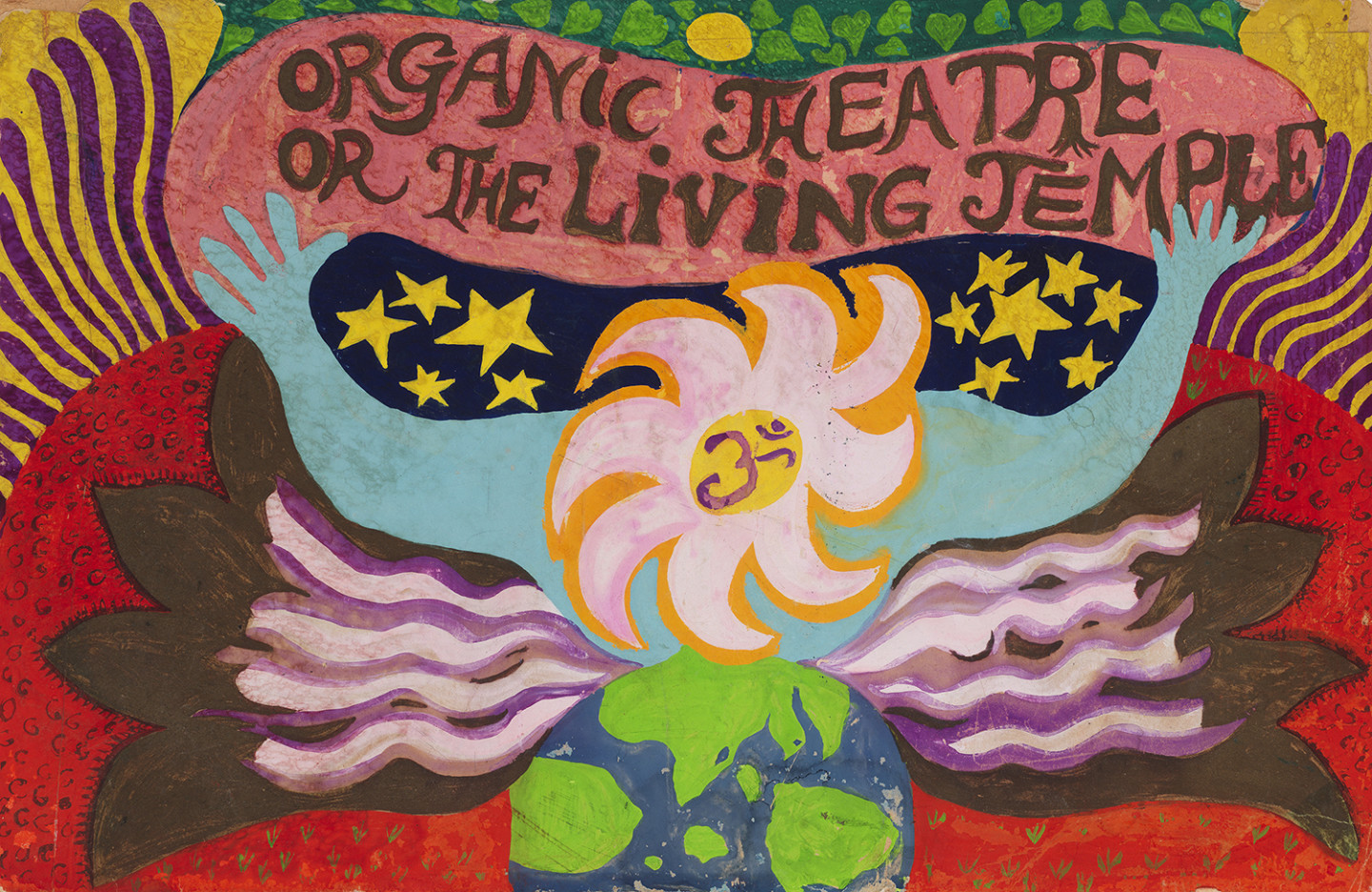

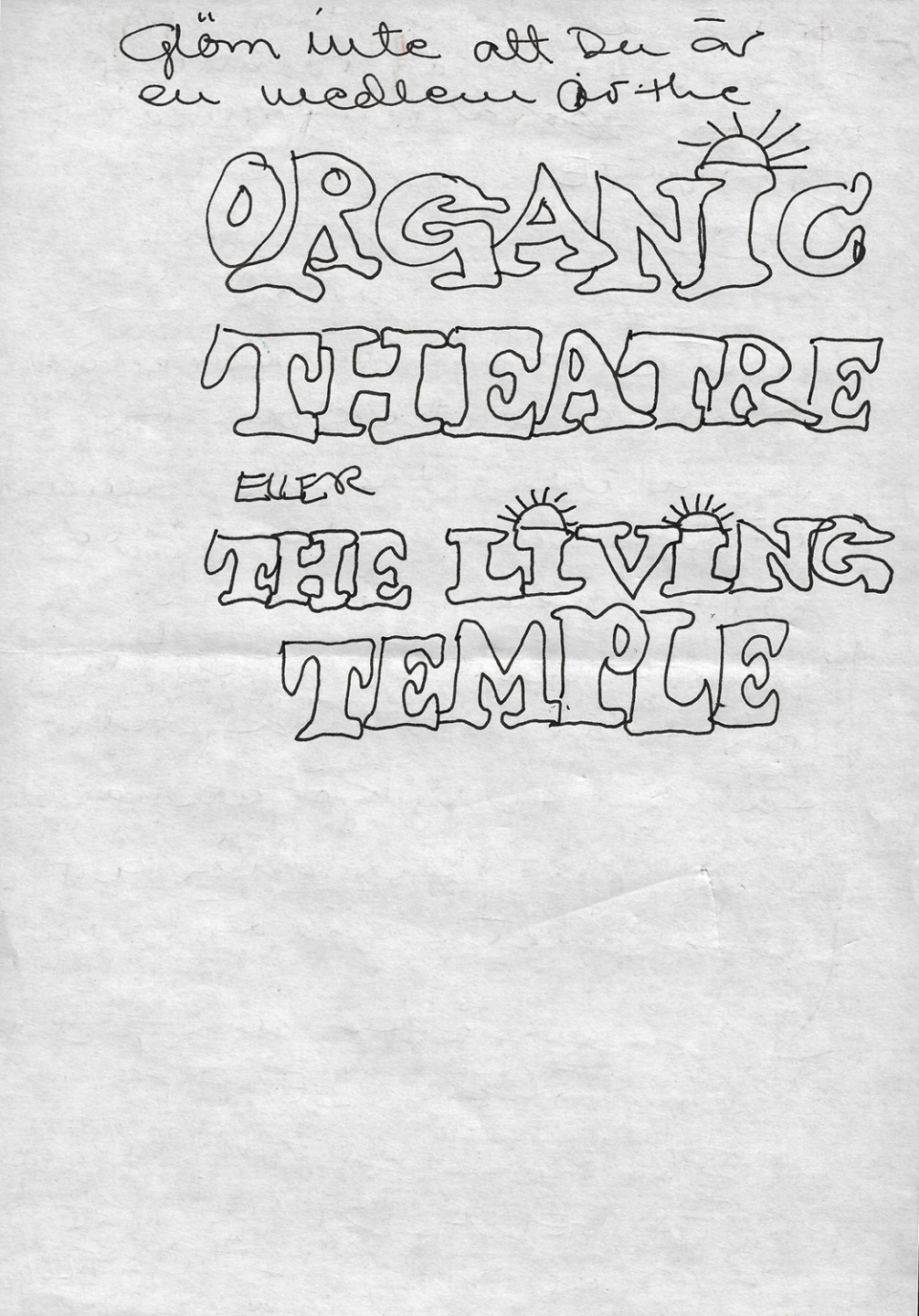

The transitory, immersive nature of theatre has a close relationship to Moki’s mobile aesthetic environments. In 1971 Moki and Don’s collaboration evolved into Organic Music Theatre or Organic Music, which Moki stitched onto tapestries, Brown Rice (fig. 11) and Organic Music (fig. 12), and painted onto Organic Theatre or the Living Temple (fig. 13), a small undated canvas painting. Like Movement Incorporated did with movement, the name Organic Music Theatre evokes theatre’s ephemerality and spectacle, and Moki even described what she made as ‘sets’[18] and ‘costumes’[19] employing the vocabulary of theatre production. Characteristically with her humour and love of wordplay, Moki described Organic Music Theatre as being ‘born’ after ‘unbelievable birthing pains’[20] (fig. 14), connecting the maternal with the theatrical and her public output. Also, in later years Moki took up different theatre-related projects: between 1978 to 1986 Moki made costumes and sets for Octopuss Teatern (‘Octopus Theatre’) (fig. 15), a children’s theatre group based out of her home in Tågarp that she founded with her friend Anita Roney, and in the nineties she worked as a set-designer at Apollo Theatre in Harlem.

Moki applied theatrical imagery to tapestries in relation to her growing spirituality in this period. Aum Expression (fig. 7), a long banner-like tapestry made in 1971, depicts four floating theatre masks – one happily smiling, one crying purple tears, one with open eyes with a speech bubble saying ‘Aum’, and one faceless humorously containing the word ‘Expression’ instead of having one. Organic Theatre or the Living Temple depicts the symbol ‘Aum’ at the centre of two embrac-ing blue arms that rise from an earth. ‘Aum’ is a mantra, considered the first sound on earth and the essence of reality in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. Moki and Don studied Buddhist phi-losophy with Tibetan lama Kalu Rinpoche between 1972–77 going to teachings and pujas across Europe and America (fig. 16). The invocation of ‘Aum’ references these roots of reality and sound in spiritual life in conjunction with Moki’s publicfacing work where spectacular visuals met with musicmaking in events. Inner life and outer life converge in this tapestry that embraces spirituality and the performative together.

Moki’s mobile aesthetic environments were produced by their emphasis on the unification of dif-ferent art forms, much like the merging of set-design, scoring, costumes and performance in the-atre. Moki had a book on Ballets Suèdois, a Swedish dance ensemble known for their elaborate touring theatrical productions. Their founder Rolf De Maré stated that ‘modern ballet…is…the synthetic fusion of four fundamentally divergent arts: choreography, painting, music and litera-ture’[21], and in one production René Clair’s film Entr’acte was shown in Relâche (‘Cancelled’) by Dada artist Francis Picabia and music by Erik Satie[22]. Similarly, visuals and music met in the collaborative Organic Music Theatre. Moki created opportunities for visuals and sound to intermingle and at her solo exhibition ‘Moki På Galleri 1′ (‘Moki at Gallery 1’) in Stockholm in 1973 there was a live concert on the opening night in front of her tapestry Relativity Suite, which is also the cover art for Don’s album of the same name (fig. 17).

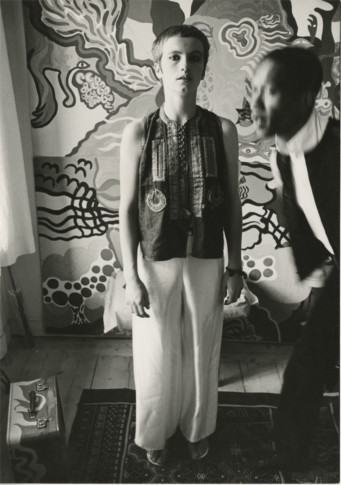

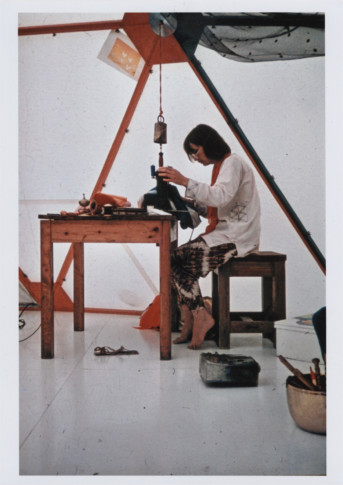

Unlike traditional theatre formats that separate performer and audience, Moki emphasised the involvement of the audience as part of her environments. At ‘Utopier och Visioner 1871-1981′ (‘Utopias and Visions 1871-1981’) an exhibition curated by Pontus Hultén at Moderna Museet, Stockholm in 1971, the Cherrys lived and shared work in a Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome for three months. Swedish artist Bengt Carling built the dome where the live-in residency took place and in it Moki made costumes that were worn by musicians, poets and the audience. Her tapestries, fabric sculptures and cushions adorned the dome and she also gradually painted a manda-la on the floor each day (fig. 18). Moki highlighted how ‘visitors participated in live music, talking, dressing up or photographing themselves in an automat and other improvised activities’[23] conveying how her visual aesthetic filled the space and came to life with the audience as participants in a mobile aesthetic environment.

Moki’s focus on immersing the audience in ‘Utopias and Visions’ traces back to her background in fashion design and the dressed body. Joanne Entwistle’s explanation in The Fashioned Body that ‘adorning the body creates an ‘environment of the self’[24] and ‘individuals learn to live…and feel at home’[25] in their bodies, is evocative of Moki’s motto ‘home is a stage’[26] and description of her work as ‘environments for the stage'[27]. At ‘Utopias and Visions’ the audience was immersed in sculptures, tapestries, paintings and could wear costumes by Moki as part of her ‘environ-mental art’[28](fig 4). Entwistle’s explanation captures Moki’s artistic trajectory and approach that extended a practice working with fashion to one that enveloped the audience in an environment of fabric creations.

In Experiments of the Everyday, art historian David Rosand states how happenings were ‘redefining the materials of art, expanding its arena and the site of its operations, from the gallery to the abandoned lot and beyond…of the transitory and the ephemeral’[29]. There are strong parallels between happenings and Moki’s mobile aesthetic environments where their transportability meant she could extend where and how her art was experienced and she even wrote about putting on ‘some form of happenings, music'[30] in Turkey in 1969. Moki’s work moved between differ-ent contexts in the home, at concerts, workshops, exhibitions or inside a geodesic dome like happenings that took place outside traditional gallery spaces; for instance, Swedish artist Claes Oldenburg used a parking lot, storefront, pool and a house as locations to put on happenings. Performances of this kind were taking place when Moki was in New York in the sixties and at Moderna Museet while she was studying in Stockholm. But as Moderna Museet curator Fredrik Liew[31] pointed out, Moki ‘worked outside of the conventional art circles (galleries, museums etc) and instead chose other formats’[32]. These ideas were in the air. Moki, in her own terms and in her work with Don, helped to expand and spread them.

Moki wrote how ‘for travelling, fabric was a great, practical solution’[33], showing how the medium she worked with needed to be mobile. Ruba Katrib’s in-depth essay about Moki, ‘Wherever We Are Is Home’, in Blank Forms’ Organic Music Societies[34] emphasises the functionality of Moki’s use of fabric for bringing her own concept of home wherever she was. Moki flipped the mobility of what was a ‘practical solution’ into an opportunity to share her vision of connecting home with stage. Moki worked with fabric to make ‘all the clothes for the family and knitted sweaters’[35] as well as Don’s multicoloured textile appliqué outfits worn across performances and workshops[36] (fig. 19) – these bodies at home and on stage activated her work. Also, the clothing and tapestries that were worn and hung together in a mobile aesthetic environment share the same technique and visual structure of cut-out bright shapes, therefore extending the reach of her vision within an environment. The varied fabrics Moki used referenced mobility too and in a letter about ‘Utopias and Visions’ her friend Tonie Roos described how the fabrics were ‘brought from all over the world’[37].

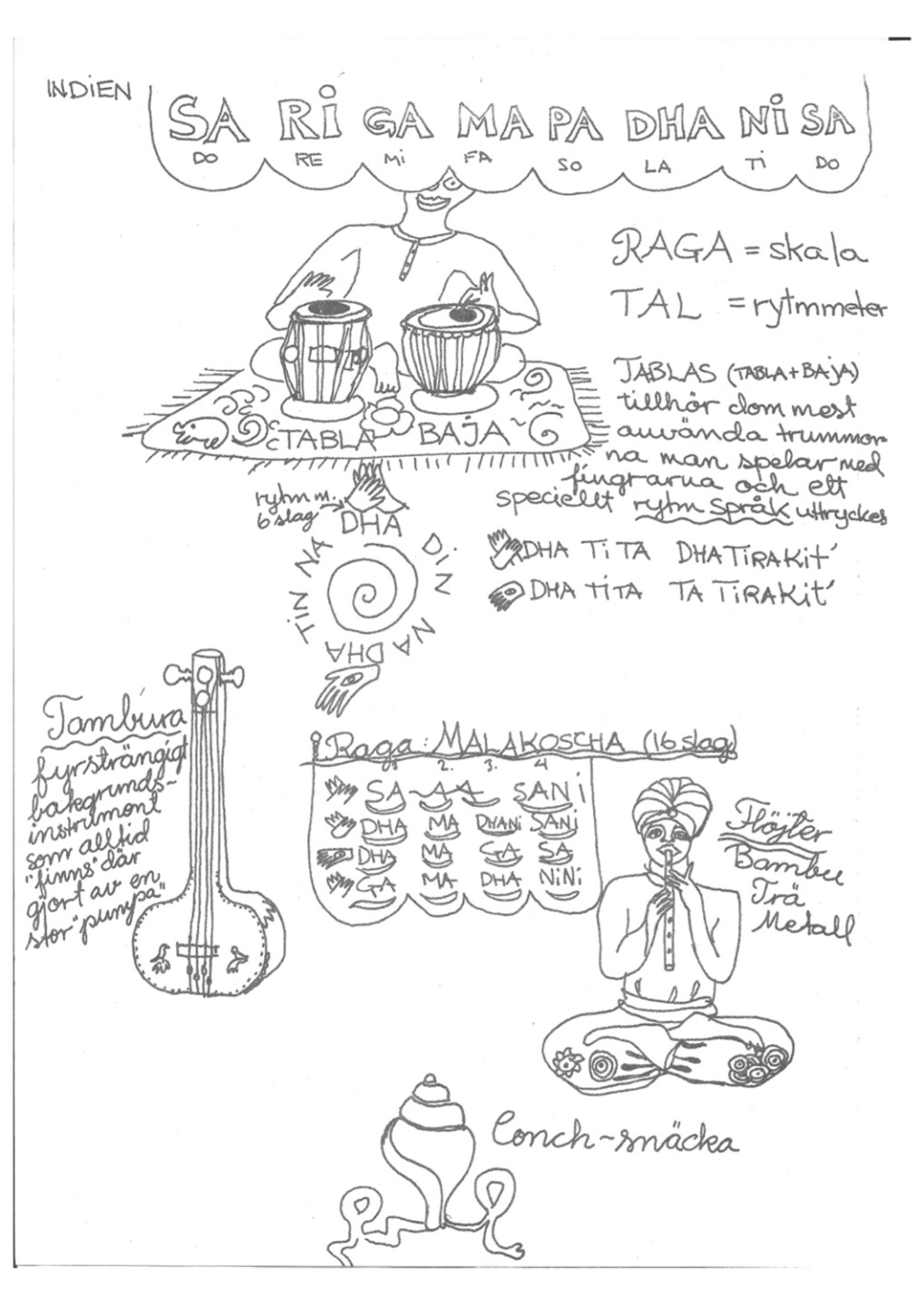

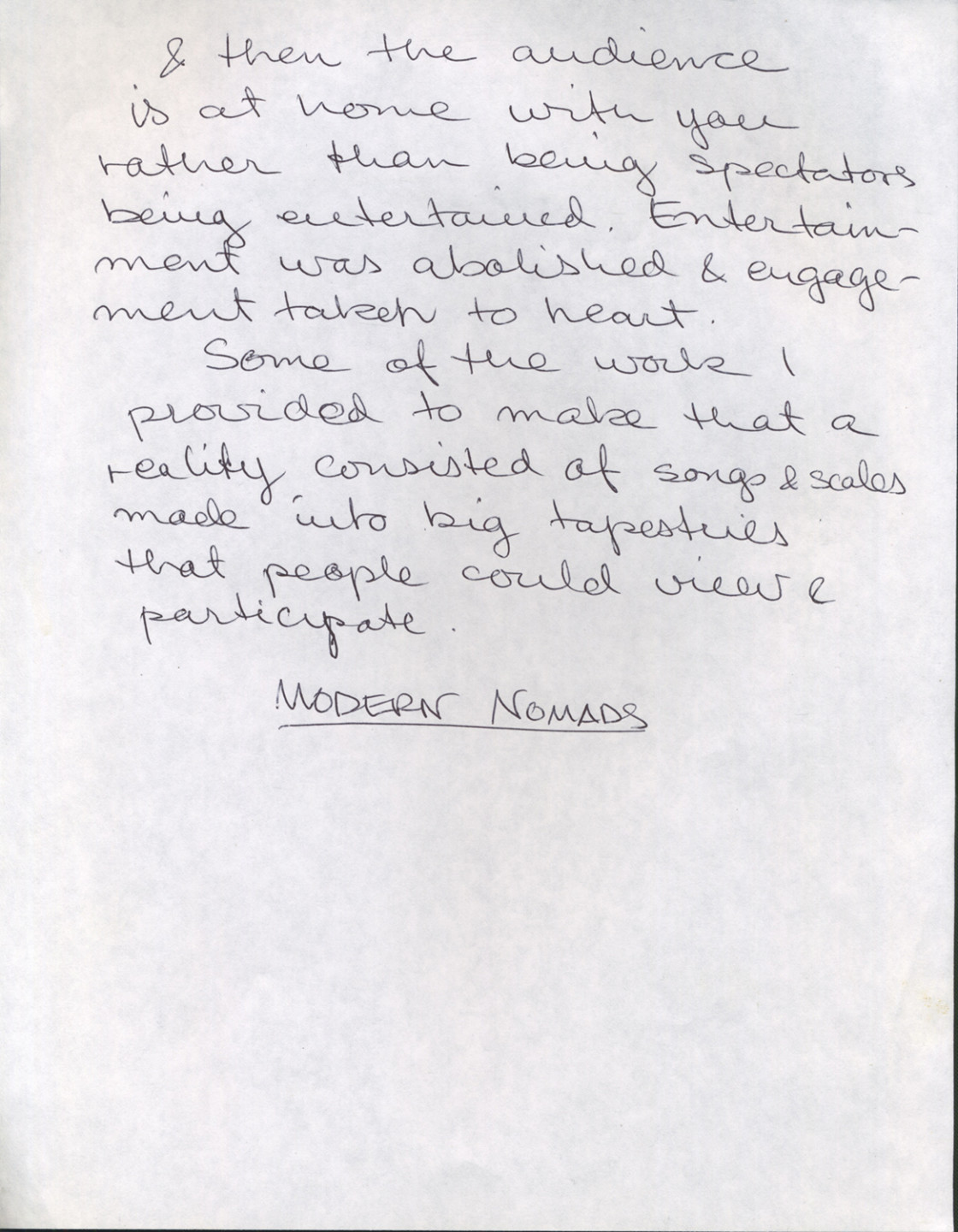

Moki also actively brought mobility into the content of her tapestries. This was her way of incorporating part of a wider pedagogical approach of sharing knowledge and involving the audience. Moki was a voracious reader of cultural history and she and Don ‘listened to music from all over the world & studied other cultures’ philosophies, other way[s] of thought’[38]. Her tapestry Malkauns Raga (fig. 5) spells out an Indian raga scale in patterned colourful fabrics and was made in 1973 when Don went to India to study with the Indian classical musician, Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar. Malkauns Raga invited access to knowledge from other parts of the world in a participatory relationship with its audience when it was used in workshops that Don and Moki ran and illustrated in a worksheet by Moki (fig. 20). On a note titled ‘Modern Nomads’, Moki wrote that some of her work ‘consisted of songs & scales made into big tapestries that people could view & participate’ (fig. 21). This again links Moki’s work to happenings in what Michael Kirby calls ‘attempts to expressively alter the audience-participation relationship’[39] in Happenings & Other Acts. For Moki, the altering of this relationship was in the audience’s activation of the tapestry’s pedagogical content. She used the stage as an opportunity to produce an expanded experience of space where ‘the audience is at home with you rather than spectators being entertained’ (fig. 21).

Visions

The mobility that shaped Moki’s life was integrated into her creative practice, but at the same time it unsettled and weighed on her. She wrote in her diary how ‘all my confusion is based on the continuous moving, the restlessness, the ever-so-unformulated future’[40], but the immersive surroundings of Moki’s bright aesthetic that dressed her family and was shared in public events offered consistency and a sense of home amid uncertainty and itinerancy. In 1968, preparing to give birth to her son, Moki used the same bold swirling multicoloured style she used for her paint-ings at this time in transforming her apartment in Stockholm. Psychedelic painted boards covered the walls (fig. 22) ‘into a world ready to receive Eagle-Eye’[41] and the following year in New York she painted a rented loft in Christie Street and a house in Congers to transform them into her idea of home[42]. Moki transformed space in the home and on the stage blurring the bounda-ries between her roles as a mother, home-maker, and artist – the mobility of her practice embodied and demonstrated this.

Moki’s vision that brought together collaboration, pedagogy, movement, ephemerality, femininity, performance in mobile aesthetic environments fed in and out of the home. The Cherrys moved into an old schoolhouse in Tågarp, Sweden, on 9th September 1970, surrounded by nature with a history of learning embedded into the building. They had been looking for ‘a place where people could come & create together'[43] that was big enough to host workshops, rehearsals and perfor-mances. Tågarp expanded an idea of what home, associated with domesticity and femininity, could be. Performances, workshops and exhibitions carried on into the old schoolhouse at the same time as Moki cooked and did house chores. All this activity occurred saturated in Moki’s visual aesthetic of hung tapestries and colourful painted walls (fig. 23) without separation be-tween art and life and with the southern Swedish landscape of forests and lakes as a backdrop. It was what Moki described as an ‘open house’[44], a ‘centre'[45] for musicians to stay, study and play music together, where children performed in ‘Octopus Theatre’ and from where Tågarp Kulturförening (‘Tågarp Culture Collective’), was based.

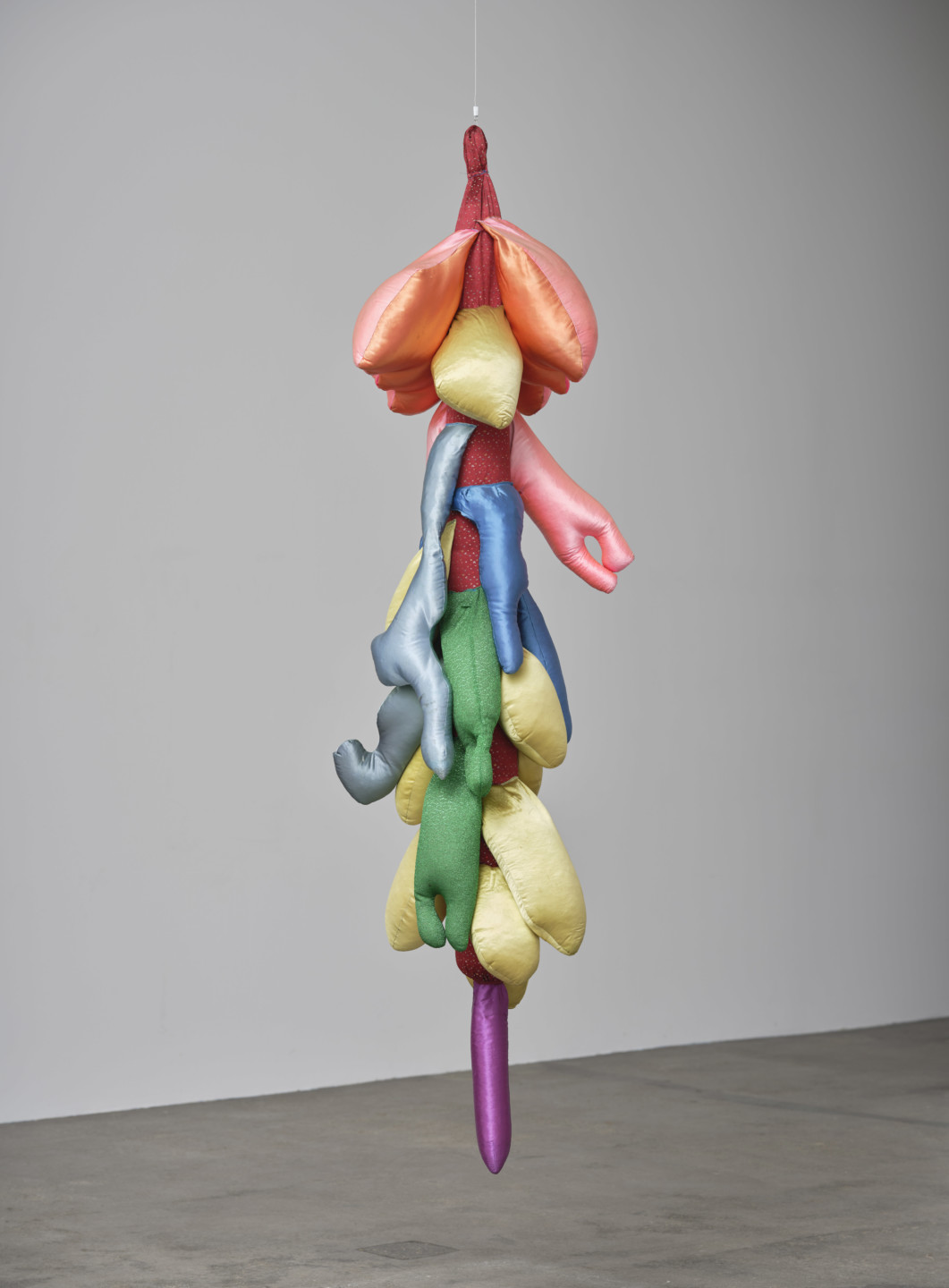

The expansion of home to the stage persisted at the core of Moki’s artistic vision. The year after her move to Tågarp, Moki brought abstracted interconnected natural and feminine forms to ‘Utopias and Visions’ in a soft hanging sculpture of stuffed dangling udders and floppy protuber-ances in multi-coloured shiny fabrics (fig. 24). The sculpture, plant-like and feminine, meets with the maximalist bright block colours typical of Moki’s work. This warped reference to nature and femininity extends the fertile creative atmosphere of home into the performative environment and back again when it was later hung by Don’s piano (fig. 23) in the Tågarp schoolhouse. Moki ex-panded forms and boundaries through her creative practice, communicating and crossing space with her mobile works. Her description of her childhood appreciation of ‘all of life’[46] and how she ‘lived in ecstasy just to see, hear, and experience’[47] nature in how it was ‘all interwoven and connected’[48] is apt to Moki’s emphasis on a converging and intermingling of art forms in an environment and beyond. What came from a search of how to communicate given her circumstances of needing to make work that was transportable became a tool for Moki to stretch boundaries and forms and carry a consistency with her through her creative practice.

Primary sources

‘1871-1981 Utopier och Visioner’ Collection. MMA MA F1a:61. Moderna Museets Myndighetsarkiv, Stockholm, Sweden.

Karlsson, Christer, Interview, 13 May 2021.

Liew, Fredrik, Interview, 4 May 2018.

Cherry Archive, estate of Moki Cherry, Tågarp, Sweden.

Secondary sources

Beta, Andy. ’Don Cherry is a deserving giant of jazz. Now his wife, Moki, gets her due as his visionary collaborator’. The Washington Post. 30 April 2021. Accessed May 2021. Link to article

Buchloch, Benjamin H. D. And Rodeneck, Judith F. Experiments in the Everyday: Allan Kaprow and Robert Watts – Events, Objects, Documents. New York: Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University in the City of New York.

Cherry Don. Where is Brooklyn?, with artwork by Moki Cherry. Recorded 1966. Blue Note, 1969, vinyl LP recording.

Cherry, Don & The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra. Relativity Suite, with artwork by Moki Cherry. Recorded 1973. JCOA Records, 1973, vinyl LP recording.

‘Chronology Exhibition and Events’. Moderna Museet. Accessed May 2021. Link to text

‘Don Cherry Universal Silence – Berlin November 3, 1972’. Inconstant Sol. Accessed May 2021. Link to text

Entwistle, Joanne. The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress, and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000.

Garafola, Lynn. ‘Rivals for the New: The Ballet Suédois & The Ballet Russes’, Paris Modern The Swedish Ballet 1920-1925. ed. Nancy Vim Norman Baer. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1 October 1995

Kumpf, Lawrence, Nygren, Magnus and Karlsson, Naima., eds. Blank Forms 06: Organic Music Societies. New York: Blank Forms, 2021.

Sandford, Mariellen R., ed. Happenings and Other Acts. London: Routledge, 1995.

Spice, Anton. ‘Rediscovering Moki and Don Cherry’s Utopian Visions’. Frieze. Accessed May 2021. Link to article

Ward, Evie. A Biography of Tapestry: Moki Cherry: Home, Stage, Museum. MA Thesis. The Courtauld, 2018.

Footnotes

[1]Vivien Goldman, ”Moki Cherry”, undated, Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry, Tågarp.

[2]Interview with Christer Karlsson, 13 May 2021.

[3]Moki Cherry, ‘The North’, c.2004-2006, Cherry Archive, estate of Moki Cherry. These writings were produced when Moki took a creative writing workshop with Arlene Raven in New York from 2004 to 2006. Moki’s diary entries and life writings from the workshop have recently been consolidated in Organic Music Societies, published by Blank Forms, a journal and resource of essays, interviews, photographs and writings focusing on Don and Moki’s collaboration.

[4]Beckmans Designhögskola, ‘Translation of Certificate,’ Stockholm, 1966, personal files, Cherry Archive, estate of Moki Cherry.

[5]Goldman, ”Moki Cherry”.

[6]Moki wrote in a note, ‘I was never trained to be a female so I survived by taking a creative approach to daily life & chores’, c.2004-2006, Cherry Archive, estate of Moki Cherry.

[7]Moki Cherry, ”Life Writings, Diaries and Drawings”, red. Adrian Rew, Blank Forms 06: Organic Music Societies, red. Lawrence Kumpf, Magnus Nygren & Naima Karlsson, New York: Blank Forms, 2021, 295.

[8]Moki recalled how they looked like ‘strange scientists’ in writing about her life with Don.

[9]This was the first of many album covers that Moki designed for Don. Her tapestries were fea-tured on Brown Rice, Eternal Now and Relativity Suite, her paintings were on the covers of ‘Mu’ First Part, ‘Mu’ Second Part and Organic Music Society, and a textile appliqué cushion is on the cover of Human Music.

[10]Moki Cherry, ”Writings on Life with Don”.

[11]Moki Cherry, ”Writings on Childhood”, ca 2004–2006, Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry.

[12]Moki Cherry, ”Writings on Life with Don”.

[13]Ibid.

[14]ABF Huset was the Workers Education Association.

[15]Moki Cherry, ”Writings on Life with Don”.

[16]Moki Cherry, hand-written timeline notes, c.2004, Cherry Archive, estate of Moki Cherry.

[17]Organic Music Theatre was joined by Frank Lowe, Ed Blackwell, Charlie Haden, Bengt Berger, Christer Bothén, Carlos Ward.

[18]Moki Cherry, ”Tågarp”, ca 2004–2006, Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry.

[19]Moki Cherry, ”Moki & Don’s Collaboration”, 2003, Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry.

[20]Moki Cherry, Letter to Tonie Roos, 1971, trans. Naima Karlsson, Cherry Archive, estate of Moki Cherry.

[21]Lynn Garafola, ”Rivals for the New: The Ballet Suédois & The Ballet Russes”, Paris Modern. The Swedish Ballet 1920–1925, red. Nancy Van Norman Baer, San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1995, 68.

[22]This production’s use of film, visuals and music in particular brings to mind early Movement Incorporated events where films and slides were sometimes shown, and one time they had a firework display in the intermission.

[23]Moki Cherry, ”Tågarp”.

[24]Joanne Entwistle, The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress, and Modern Social Theory, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000, 6.

[25]Ibid.

[26]Moki Cherry, ”Moki and Don’s Collaboration”.

[27]Ibid.

[28]Moki Cherry, ”Life Writings, Diaries and Drawings”, 299.

[29]David Rosand, ”Foreword”, Experiments in the Everyday: Allan Kaprow and Robert Watts – Events, Objects, Documents, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh & Judith F. Rodenbeck, New York: Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, New York, 1999, ix.

[30]Moki Cherry, ”Timeline”, undated, Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry.

[31]Liew curated ‘Moment’, an overview exhibition of Moki’s work at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 7th April 2016 – 9th April 2017.

[32]Interview with Fredrik Liew, 4 May 2018.

[33]Moki Cherry, ”Life Writings, Diaries and Drawings”, 287.

[34]Ruba Katrib, ”Moki Cherry: Wherever We Are Is Home”, Blank Forms, 06: Organic Music Societies, New York: Blank Forms, 2021, 157–187.

[35]Moki Cherry, ”Writings on Life with Don”.

[36]Moki also designed and made the jumper that Don is wearing in a photograph by Francis Wolff on the cover of Symphony for Improvisers, released in 1968 on Blue Note.

[37]Tonie Roos, ‘Utopias and Visions,’ c.1971, letter, ‘1871 – 1981 Utopier och Visioner’ Collection, Moderna Museets Myndighetsarkiv, Stockholm, Sweden.

[38]Moki Cherry, ”Writings on Life with Don”.

[39]Michael Kirby, ”Happenings: An Introduction”, Happenings and Other Acts, red. Mariellen R. Sandford, London: Routledge, 1995, 14.

[40]Moki Cherry, ”Life Writings, Diaries and Drawings”, 298.

[41]Moki Cherry, hand written timeline notes, ca. 2004, Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry.

[42]Moki described in her diaries that she painted and renovated a loft in Christie Street, NYC like how she did in Stockholm, but that she found it unbearable and wanted her children to be in the country. They then moved to a house in Congers, a suburb of New York City, that she painted in bright colours.

[43]Moki Cherry, ”Tågarp”.

[44]Moki Cherry, ”Writings on Life with Don”.

[45]Moki Cherry, ”Tågarp”.

[46]Moki Cherry, ”Writings on Childhood”.

[47]Moki Cherry, ”Life Writings, Diaries and Drawings”, 271.

[48]Ibid.