Installation view, 2024 Photo: Helene Toresdotter

The artworks in “Unhealed”

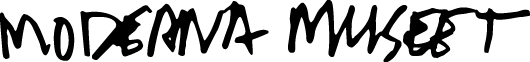

Héla Ammar, Tarz (Weaving time), 2014

In Tarz (Weaving time), Héla Ammar mixes her own photographs, taken during the Tunisian revolution, with historical photographs and documents. Together these important fragments chronicle a political history of Tunisia, a history that started long before the Jasmin Revolution and that is still in the process of unfolding.

‘Tarz’ means embroidery in Arabic and Ammar uses the red thread to emphasize how different historical events are closely linked to one another and form a continuum into the future. Whilst evoking the Tunisian flag and paying tribute to the martyrs’ blood, the embroidered red silk also recalls qualities traditionally associated with women, such as “patience, self-sacrifice, and precision.” According to the artist, these are qualities that have been paramount in the complex political process of Tunisia.

Héla Ammar b. 1969 in Tunisia, lives in Tunis.

Mario Rizzi, Kauther, 2014

This film portraits the female activist Kauther Ayari. She was the first person to publicly address the demonstrators in Tunis at the start of the Jasmin Revolution in 2011, calling for work, freedom, and dignity, and inspiring other to do the same.

In a captivating monologue, Ayari reflects on the political developments in Tunisia, but also on her own life story, and how it has been severely marked by harsh patriarchal oppression. At moments, the screen fades to black as the sounds of Kauther’s poor neighbourhood, the cries of her children, and a love song she sings while cleaning and tidying up, resonates with her words, underlining her still unsettled life.

While paying tribute to this remarkable woman, this film also raises questions about the writing of history: Who will be remembered in the history books, and who will be condemned to oblivion?

Mario Rizzi b. 1962 in Italy. Lives in Berlin.

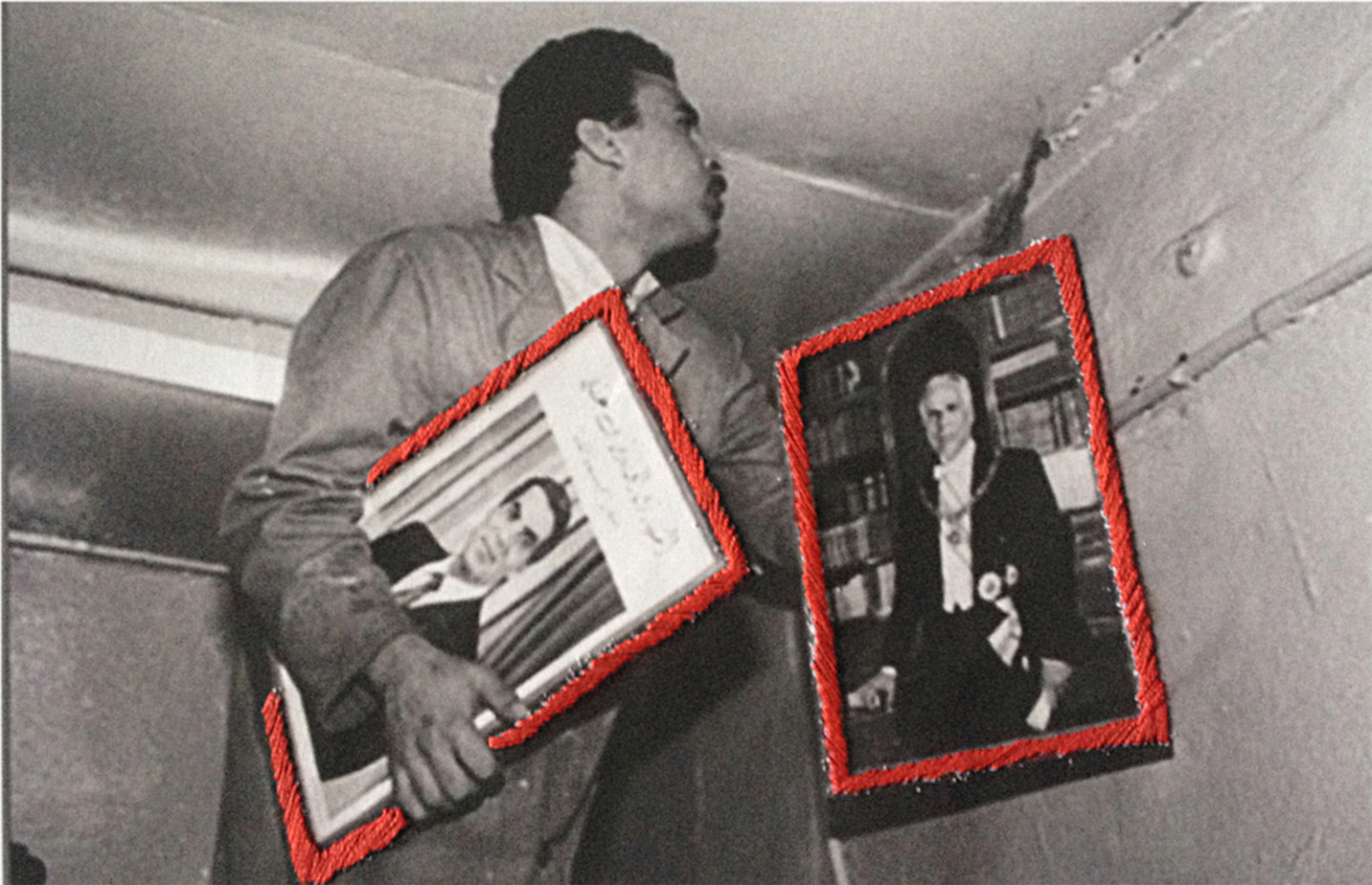

Muhammad Ali, 366 Days of 2012, 2012

366 Days of 2012 is a diary and a witness account. The work consists of 366 drawings made in Syria, throughout the year of 2012. The drawings are placed in twelve rows, each corresponding to a period of one month.

This diary belongs to a larger group of works that portray how the people of Damascus changed during the war years of 2012–2015. The artfully drawn figures seem rooted in a mythological and fantastical past, yet they also show signs of mutation and degeneration. If these creatures were once human, a fierce struggle for survival has effectively stripped them of their humanity and transformed them into something else.

In 2015 Muhammad Ali fled Syria and the project capturing the social degradation of his home country thus came to an end.

Muhammad Ali b. 1982 in Syria. Lives in Stockholm.

Moataz Nasr, Khayameya, 2012

The work borrows it’s title from the traditional craft of tent-making, which is made by layering colourful fabric into intricate designs inspired by Islamic ornamentation and traditional Egyptian designs.

The use of matches in the work, to create the patterns of Khayameya, speaks about the aftermath of the recent revolutionary history of Egypt. During his regular walks in the old town of Cairo, Moataz Nasr noticed that historic locations and artifacts were being destroyed and looted.

Through his work, the artist declare his love for the city and his concern about the destruction of cultural heritage.

Moataz Nasr b. 1961 in Egypt. Lives in Cairo.

Mouna Jemal Siala, No to Division, February 2013 to November 2014

Mouna Jemal Siala made this artwork in response to the tragic assassination of Tunisian opposition leader Chokri Belaïd, a deed that created political turmoil. Fuelled by concerns over escalating violence and societal divisions, she drew a line on her face as a symbolic stand against growing polarisation.

This artistic protest unfolded in the city of Tunis, where she engaged with people, inviting them to participate, and capturing their reactions to the increased division. Between February 2013 and November 2014, the artist met, conversed with, and photographed 217 individuals, mirroring the number of Tunisian parliament members. Through her work, Mouna Jemal Siala emphasized that these people, in contrast to those fostering turbulence, truly represented the voice and essence of Tunisia, more than any politician.

Mouna Jemal Siala b. 1973 in France. Lives in Tunis.

Khaled Hafez, Military Industrial Complex, 2022 – 2023

This work by Khaled Hafez, specifically conceived for the Unhealed exhibition, was prompted by a question posed by one of the curators: Reflecting on the more than ten years that have passed since the uprisings and revolutions spreading across the Arab world, how would you characterize the current moment? In his response, Hafez goes beyond capturing the Middle Eastern moment, reflecting instead on a globalised world where militarization is infiltrating our existence from all directions.

With parents that both worked in the medical corps of the Egyptian army, Hafez has always integrated military elements into his interdisciplinary artistic practice. He creates contemporary hieroglyphs – based on military iconography— that emulate the language of subjugation and power into what he describes as “globalized media-propagated war imagery.”

Khaled Hafez b. 1963 in Egypt. Lives in Cairo.

Marwa Al-Sabouni, The Battle for Home, 2015

The displayed illustrations and texts are excerpts from The Battle for Home, a book by Syrian architect Marwa Al-Sabouni. Drawing from her personal experience residing in war-ravaged Homs, Marwa unfolds the painful and tragic narrative that Syria has endured for years, marked by widespread destruction, loss of lives, and massive displacement. Within her book, she describes how the built environment affected the community and how the plans imposed on cities like Homs, by those in charge of public space, have contributed to the conflicts. Through the chapters, she shares with us her eyewitness of her country, intertwining the terrible tales of destruction and loss with a resilient hope to rebuild and prevent devastation from occurring again.

Marwa Al-Sabouni b. 1981 in Syria. Lives in Homs.

Hadia Gana, Zarda, 2011 – 2018

Empty bottles and other discarded food packaging are scattered on the ground. Product names and tables of contents have been replaced with names of individuals who sacrificed their lives for the Libyan revolution.

The word ‘Zarda’ can refer to a picnic, but also a state of chaos. While paying tribute to the martyrs, this artwork also comments on the social reality of today’s Libya, and on the tendency of the population to forget the sacrifices that were made to create a different future.

With ashes on the ground is written, “The lives of the martyrs will not go in vain,” a common slogan during the revolution. However, at any moment, the ashes risk spreading across the floor, potentially causing loss of legibility and the triumph of oblivion.

Hadia Gana b. 1973 in Libya. Lives in Tripoli.

Selim Ben Cheikh, Ur serien Horizontal Vertical Horizontal, 2023

Using acrylic spray, Horizonal, Vertical, Horizontal was created by allowing clouds of paint and dust to gently settle on the canvases, positioned horizontally on the floor. This series of paintings belong to a larger body of works that respond to the crisis of 2013 and the political vagueness that Tunisia has experienced ever since.

At first the artist wanted to capture the frustration of not being able to envision even the immediate future, and to convey the feeling of navigating through a seemingly endless blur. Over time, however, this sense of frustration gave way to a growing fascination with obscurity, and with its perpetual shifting of lights and hues.

Covering all the glazed doors and windows of the exhibition space, the Arabian Spider (another work by Ben Cheikh) appears as a decorative pattern associated with a unifying cultural heritage. At closer inspection, however, the swirling arabesques reveal themselves to be made of barbed wire, as if threatening to divide, exclude, and isolate, rather than unite.

Selim Ben Cheikh b. 1979 in Tunisia. Lives in Akouda.

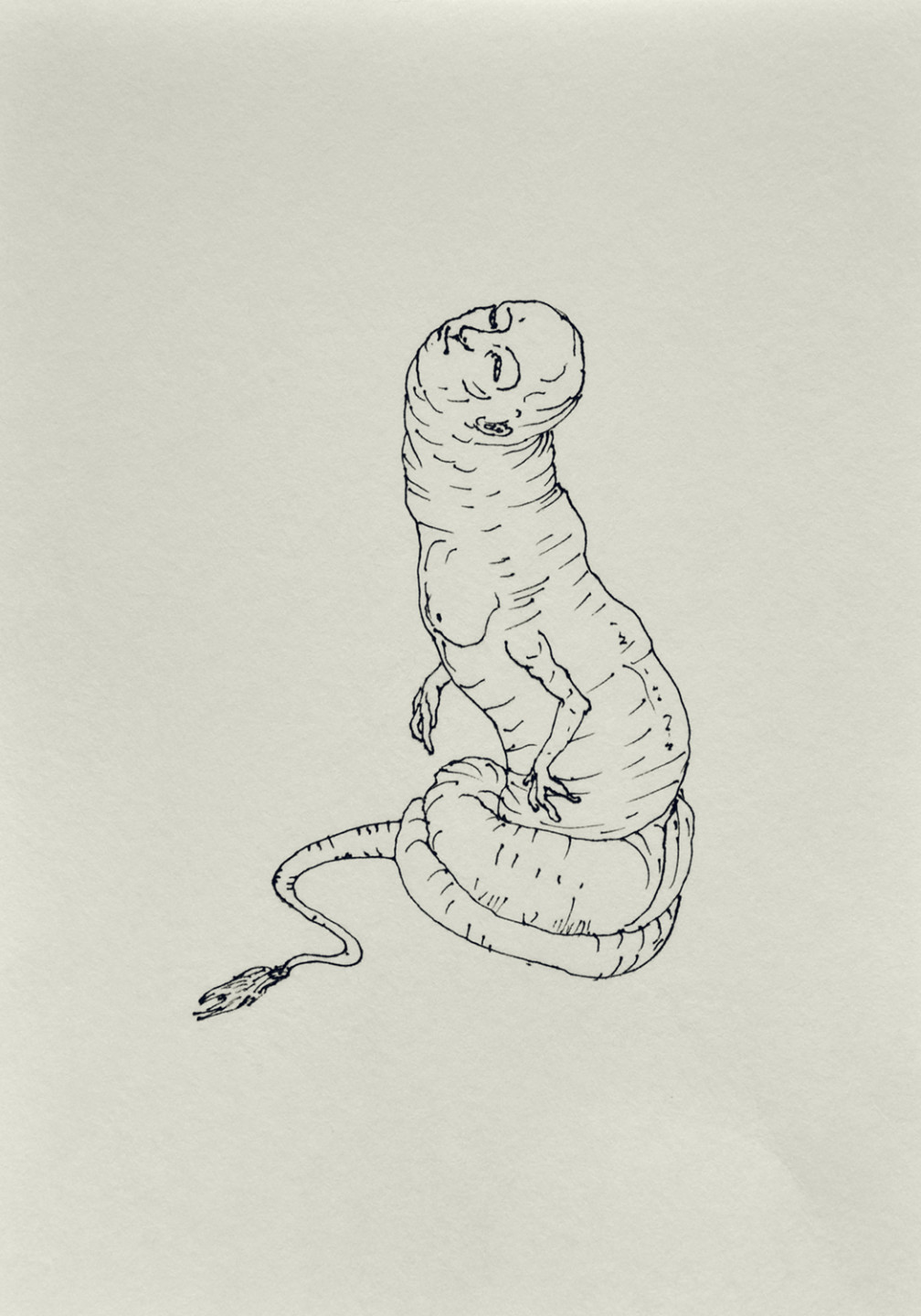

Adrian Paci, Broken Words, 2019

The video installation Broken Words presents five individuals, all of whom have fled their native Syria. Adrian Paci, who himself has experienced societal upheaval and forced migration, asked these people to share with him, their personal experiences of the civil war.

When editing the footage, Paci focused exclusively on the sequences where the protagonists pause in their narration – waiting for the interpreter’s translation—and created a group of silent portraits. In a second step, he worked with their voices, creating a mix of sounds that avoids conveying a precise narrative, but preserves the density of the experience they express.

As if to emphasize the impossibility of fully understanding a fellow human’s traumatic experience, this artwork only allows us to hear and see fragments of something larger that remains elusive. At the same time, a human bond is manifested in the intimate meeting between faces, as if between mirrored souls who have seen, experienced, and felt things that words might not be able to convey.

Adrian Paci b. 1969 in Albania. Lives in Shkodër and Milano.

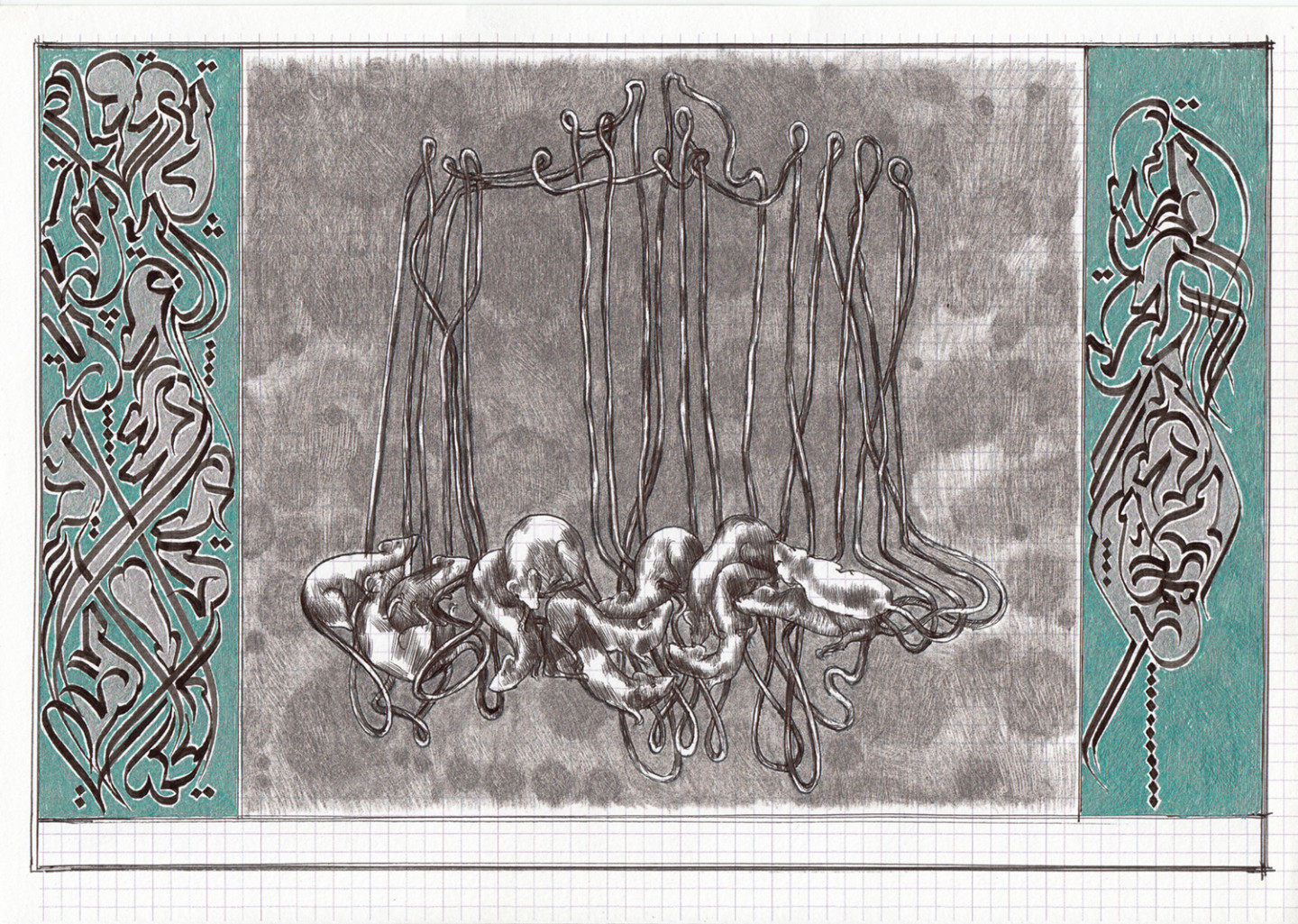

Shady Elnoshokaty, Magnificent Mind, 2004 – 2013

These drawings were selected from the Magnificent Mind project, which was initially conceptualized as an artist book. Each drawing resembles a theatrical scene, where intense psychological and bodily energies are in the process of forming entangled cells, within a constricting and stifling society. The central room in each scene is constituted by the mind, which emerge with silence, stillness, and clarity, while the sounds of bodily energy resonate loudly. As part of the work, a new and unreadable language has been developed, inspired by Arabic calligraphy and reflecting on societal complexities.

Magnificent Mind is an untold story that has never before been displayed or printed, according to the artist “because of the loss of energy and spirit after the collapse of the Egyptian revolution and the dramatic, radical changes in Egypt and the Arab region since 2013 to the present day.”

Shady Elnoshokaty b. 1971 in Egypt. Lives in Cairo.

Safaa Erruas, Flags, 2011 (reproduced in 2023)

The Flags series was created in 2011, as a contemplative response to the uprisings and revolutions. With delicate embroidery, Safaa Erruas reproduced the flags of the 22 Arab countries constituting the Arab League union – an organisation repeatedly criticized for its internal conflicts and collective inaction on critical international issues.

For many years, Erruas has immersed herself with the monochrome, focusing mainly on the different nuances of white. Following this line, the artist has embroidered each flag with white pearls on white cotton paper. The intentional absence of other colours signals fragility and vulnerability. By presenting all flags in white-on-white, the artwork takes on a discreet form of mourning, embodying a profound yet subtle expression of disappointment.

Safaa Erruas b. 1976 in Marocco. Lives in Tetouan.

Diana Jabi, Home Sweet Home, 2016 – ongoing

The war in Syria prevented the artist from coming back home and forced her to live abroad. In her work, Diana Jabi keeps thinking about the meaning of losing and missing her home. This deep, sad feeling that you can never fully understand nor make disappear.

For Jabi, it is the old town of Damascus where she feels homecoming, and by embroidering the map of the ancient city of Damascus, she expresses her fear of the city being destroyed as many other places in Syria.

Three works have been selected from the artist’s collection that encompasses ten in total. All of them incorporate stories related to the artist’s life and what is going on around her. She meditates with her pieces while envisioning her sacred place, believing that we can protect our beloved places by keeping them alive in our thoughts.

Diana Jabi b. 1982 in Syria. Lives in Bucharest.

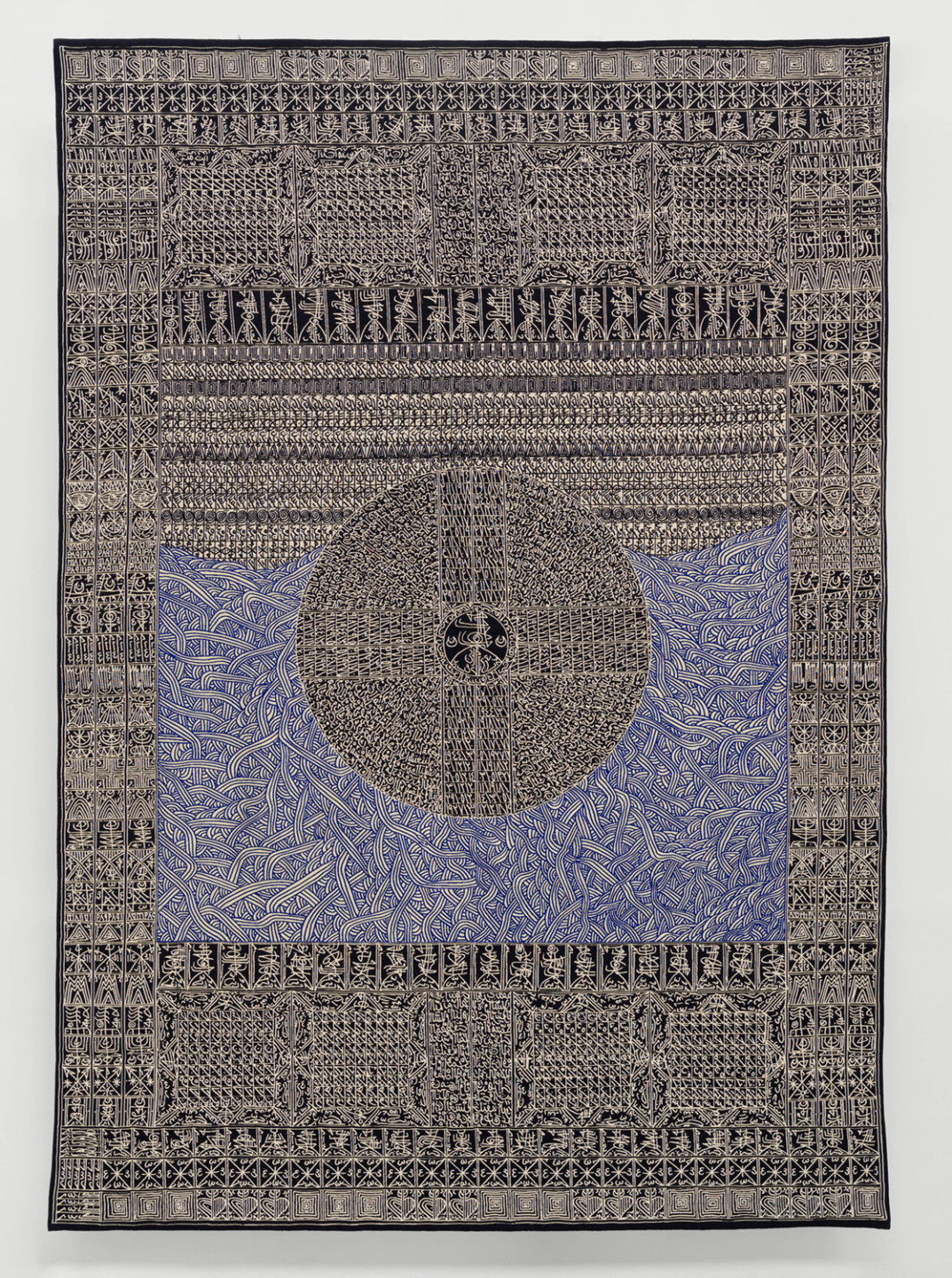

Rachid Koraichi, Jardin d’Afrique (Garden of Africa), 2021

Jardin d’Afrique (Garden of Africa) is a garden paradise conceived by the artist Rachid Koraichi as a final resting place for anonymous migrants who have died in the Mediterranean Sea, while searching for a better life. It is a UNESCO-recognized site in the coastal town of Zarzis, southern Tunisia, initiated and financed by Koraichi to bury and remember these victims with dignity, no matter where they come from or their religion.

The woven tapestry depicts a part of Jardin d’Afrique and incorporates important ideas behind the cemetery in the shapes of symbols, glyphs, and ciphers. The artist refers to his visual vocabulary as an alphabet of memory— drawing on a wide variety of languages and cultures, to transmit history, faith, and life.

Rachid Koraichi b. 1947 in Algeria. Lives in Paris and Tunis.

Aya Albarghathy, From the series Life Could End, 2021 – ongoing

In Benghazi, women cannot walk the city freely. We park the car directly in front of our destination, and if we really need to walk, we are accompanied by a heavy feeling of anxiety. How did we end up being confined in this way? When did attempts to share the public space begin to be met with direct violence?

Our ears catch the wailing of the hyenas as they wander among their prey. We avert our eyes in attempt to escape. Still, we walk the Corniche and imagine an escape to the sea, stand still for a moment in front of the captivating blue horizon.

(From the artist’s writings on the series Life Could End)

Aya Albarghathy b. 1999 in Germany as a Libyan citizen. Lives in Benghazi.

Asim Abdulaziz, 1941 (2021)

What are the psychological effects of living in a prolonged state of war? Asim Abdulaziz’s short film 1941 unfolds inside a decaying Hindu temple in the artist’s hometown of Aden. Within the temple’s walls, ten shirtless men – spanning different generations – are deeply immersed in the act of knitting, all using the same blood-coloured yarn.

The film draws inspiration from a 1941 article, describing how American women, during World War II, sought solace as well as tried to contribute to the war effort, through knitting. Associated with women history and female caring, this meditative craft is here transposed to a Yemeni (and male) reality. Whilst the deteriorating temple may symbolise the state of the entire country, the knitting men seem to be ensnared in an unyielding present, trapped in numbness amidst anxiety and fear.

Asim Abdulaziz b. 1996 in Yemen. Lives in Aden.

Fethi Sahraoui, Youthupia: An Algerian Tale, 2019

In 2019, Algerians gathered in the largest popular uprising against then Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika (who sought a fifth presidential term), to manifest their rejection of the perceived corrupt elite that governed the country. Emersed in this resent history of Algeria, Fethi Sahraoui’s video Youthupia: An Algerian Tale tells an interesting story about the links between politics, youth culture, and football.

70 percent of the entire population of Algeria are youth and in the video we see how many of them find a place to express their thoughts and feelings in the stadium. During the uprisings, these young football fans brought their engagement and enthusiasm from the stadium to the streets, actively participating and even leading the demonstrations. As a consequence, the political protests came to resonate with songs derived from football fan chants, now transformed into powerful slogans against corruption.

Fethi Sahraoui b. 1993 in Algeria. Lives in Algiers.