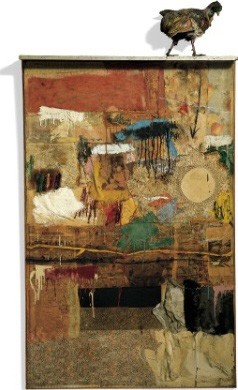

Robert Rauschenberg, Satellite, 1955 © Robert Rauschenberg/Untitled Press, Inc./BUS 2007. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

After word from the catalogue Robert Rauschenberg: Combines

He uses color with an authority that’s almost from another century, a true painter’s relationship to color as some musicians have ab-solute pitch. Yet he works in monochromatic ranges with equal richness.

I feel that the Combines radiate poetry. Maybe this poetic feeling comes from Rauschenberg’s economy of color in some of the works in order to reinforce a simple poetry, to not complicate it but to let it be very pure in the formal sense. This goes for the associative sense as well, because obviously different objects are elements coming from the world of constraint, the world called reality, and into the world of art. As ropes, fabric, photographs, or pieces of metal, they carry associations, and these associations are an important part of the poetic send-off that his sculptures offer. He often avoids additional color to keep this poetry pure. This can also be seen in some of his drawings, where the purity of black on white paper has the same strong effect using simple means to carry very strong feelings. Of course, some of the sculptures have their own inherent color from their range of found objects, as the work of John Chamberlain does, but in many of the sculptures there is no additional paint, and they are more monochromatic in scale.

There is a sense of improvisation in Rauschenberg’s work that comes out of discipline and experience. He knows exactly the moment when something is right. I wonder how controlled the process of art-making is for him—if conscious decisions occur or if the making takes place in a trancelike state, of seeming consciousness. It seems to me that sometimes you could not reason, you could not find this agreement between elements in reason, you’d have to find them in a trance.

He chooses the most junky stuff possible to be able to make the “click” happen, the moment they transform from material to poetry. If the click doesn’t happen, it’s absolutely nothing—inert, worse than junk. It’s a failed action. But for Rauschenberg the click does happen, and the effect of the click is somehow more important the junkier the incorporated elements are. He takes the most rejected parts of our surroundings and makes them the most beautiful. It’s by a kind of magic. There must be a challenge, in the sense that they are so awful, before the transformation happens.

In further considering Rauschenberg’s use of color, there is a lot of shade and shadow. Shadow is an important part of the sculpture in this world of his. It has an interesting relationship to his black-and-white photography. Sometimes, when we say monochrome it is not necessarily black and white. I remember when the cardboard pieces were first made, they were a shock to people because of the pure color schemes and poor materials that this master of color used. Rauschenberg’s use of the poorest, most thrown away, and rejected things, things that people avoid seeing, intrigues me very much. It’s almost like a program, maybe of a social or philosophical kind. It has a certain religious element. I have a feeling it’s something important for him. In our generation (which I can say because we’re of the same generation), I think it was a critical experience or discovery for us that things that are important very often are the least considered, on all levels of life. People weren’t always looking for what was best for them, and the great things in life were sometimes the most simple, and hidden, too—hidden behind conventions. We had been taught cer-tain values, and it took people like Rauschenberg to show us how hollow these conven-tions are.

For him, this is demonstrated through the sculpture, by the simplicity of the opera-tion, by the simple magic. A piece of junk all of a sudden, by unconventional operations, became indescribable, became poetry. The previous generation, if you think about Piet Mondrian, or even Jackson Pollock they tried so hard. They were so phenomenally ambitious and moral that somehow they overshot the target. I think what Rauschenberg introduced was a way to say it more simply, to make it more direct. You can say that Kurt Schwitters tried to do it in a simple way. There has, of course, been a lot of discussion about the difference between Rauschenberg’s and Schwitters’s work. I think one difference is the ease of Rauschenberg’s—there appears to be no effort.

Although Schwitters was a great master, there is in his work the presence of self-consciousness, ambition, and, of course, politics. However, the ease of Rauschenberg’s work lifts up and flies away in the poetic sense, which comes from the fact that you see no struggle. It’s just as easy as words, as talking, as part of a phrase, and it results in great beauty. This is something American, I think, in the sense that in America there is enough freedom from heavy tradition, as well as the very different sense of space in America and in American art—the essential role of space without limitations, the great freedom of space, the fact that there’s a lot of it, and scale is very large. Pollock had already discovered that in some sense, although strangely enough, while his dripping demonstrates a fabulous freedom, there is still some kind of compulsion to make great work, to impress people. Whereas in Rauschenberg’s works, there is anti-ambition. There is joy and total ease. They seem to come without struggle and baggage; there’s nothing weighing them down.

The radiance of Rauschenberg’s tormented pieces of metal or his abandoned ob-jects, his pieces of reality where constraint has mismanaged them into victims of their lives, that’s a part of the emotional radiance, the way they radiate life. The way that they have been conceived, used, destroyed, and then recuperated tells us a life story of the object, of the fragment which is a part of something humanistic. There’s a humanistic element—it’s never too late. There is great optimism.

When Rauschenberg’s works were first shown in Europe, it was a great shock for many people. I saw the first show in Paris in 1961. It was something that we had waited for. It was like a revelation in one way, and a confirmation in another. Finally, something was shown that was so strong and so powerful. For me, I can’t say it was a surprise, it was more like, ah, finally somebody did it right.