Photography and Man Ray. Notes by Leif Wigh

With his versatility, his boundary-crossing images and objects Man Ray (1890-1976) anticipates much of the postmodern art of the late 20th century.

He painted and took photographs, made sculptures and objects, drew and made motion pictures. He made use of the new media technologies that turned up on the commercial market. He turned against what was traditional and, in his own work, often provided a comment on it. He found the motifs of his pictures among the men and women who moved in artistic circles in Paris and, not least, among the objects that he found in Parisian flee markets. His most creative period as a photographer was between the first years of the 1920s and 1940 when the Nazis invaded France. In that year he was obliged to leave Paris. It was during the interwar years in France that he became best known as one of the surrealists. His studio became something of a gathering point for younger artists of all nationalities. During this period his work was included in various group exhibitions. But it was not until the 1960s that his status as an artist became established in a succession of solo exhibitions. Our own time views him as both a photographer and a traditional type of artist depending on the point of view of the observer. The principal source of information about Man Ray’s work and his activities comes from his autobiography, where he lays down how he wishes to be seen by posterity, giving his own opinion of himself and his works. Whether his text actually reflects the historical truth is surely of lesser importance in a context like this. It is Man Ray’s imaginative and humorous works that offer the viewer the truth.

Photography developed rapidly as an art after World War I. Pictorialism, the style that had been dominant since the final years of the 19th century, gave way during the 1920s to Neue Sachligkeit, New Objectivity or, if one wishes, the new photographic objectivity. In the period from the 1890s up to and during World War I, slightly blurred photographs made using a soft-focus lens were characteristic. But there were also photographs in which silver had been replaced by light-sensitized colour pigment. These were used for indoor portraits in which gloom predominated, the gradations and nuances were limited and there were large dark areas. After the war the young photographers made use of the possibilities afforded by new technical advances. In their view, photography no longer needed to imitate art prints or drawings to be considered a serious work of art. A modern photographer could be true to him or herself and yet create art. This was a change of attitude that contrasted starkly with pictorialist images which sought always to imitate art prints or drawings. The photographers of the interwar years had new, sharply focused instruments at their disposal. There was the Ermanox camera, known as the Cyclops, with its sensitive lens and there was the Rolleiflex with its 6x6cm format that offered twelve exposures on a reel of negative film. These two cameras were used principally by press-photographers. Higher definition lenses were produced as well as more sensitive negative film. This enabled photographers to catch brief moments from people’s lives at places of work, on the city streets and at home. Straight lines and geometrical forms in photographs of architecture and design created a powerful dynamic tension. At the same time photographs helped both architects and designers to demonstrate their products. The metropolis with its dynamic life often proved the best motif in the world of photography at the time.

But in portraiture and (the new) advertising studios photographers continued to use larger cameras with larger-sized negatives. One reason for this was that the larger negative made retouching easier as well as making contact prints a possibility. This, in turn, gave crisper images and better reproduction of nuances than the smaller negatives could manage. Even if the new cameras with their sensitive lenses and the new photographic materials gave a rich potential, photographers also discovered how they could compose their pictures and create exciting visual solutions and dynamic effects. Using the new cameras one could study the subject very closely. Sharp and clear and unconstrained pictures were taken of the products of industry and of the densely populated society.

The American photographer Alfred Stieglitz had already documented the life in the metropolis early on and depicted both the arrival of immigrants and the terminus of the horse-drawn trams, in pictures also showed the rapid growth of New York with its increasingly expensive plots and the ever higher buildings that resulted. Stieglitz was also the owner of the classical art gallery known as 291 on Fifth Avenue where modern European art with names like Picasso, Braque and Picabia were shown, but also photography. Stieglitz exhibited both his own photographs and those of his friends. One visitor to the gallery that was inspired by what he saw was the young Paul Strand, who now appears as the first modern photographer with modernistic works like Wall street New York, 1915, Abstraction Bowls Connecticut, 1915, Blind Woman New York, 1916, and The White Fence Port Kent, New York, 1916.

Another young man who visited 291 at the same time was Emmanuel “Manny” Radnitsky, who worked as a commercial draftsman in the advertising industry. In the evenings he studied at the Ferrer School. Manny Radnitsky, who was the son of poor Russian immigrants, was born in Philadelphia and had moved to Brooklyn when he was seven. He showed an early aptitude for drawing and painting and, on leaving school, received a scholarship to train as an architect. But he chose instead to study painting. During the 1910s the family shortened and americanised their name to Ray at the suggestion of Manny and his younger brother Sam. Manny started to call himself Man Ray.

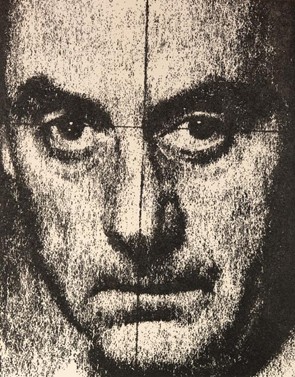

At the 291 gallery Man Ray saw the possibilities offered by photography. He started to take pictures himself, principally in order to be able to reproduce his own paintings and drawings. In 1913 he moved to an artists’ collective in New Jersey. After a number of years there he made the acquaintance of Marcel Duchamp who had fled from wartime France. With his unique and technically beautifully produced works of art, Duchamp became an influence on Man Ray. Together the two men started a version of Dadaism in New York. Sometime after the end of the world war Duchamp returned to Paris. In the early 1920s Man Ray began to think in terms of a trip to Paris. This notion was reinforced when he came to realise that there was no future for dadaism in New York. Stieglitz, who had taught him the basics of photography, advised him to apply for the money to go to Paris from an art collector who had purchased some of Man Ray’s works. At the time the French capital was the focal point of modern art and it hosted both the expiring Dada movement and the growing surrealist tendency. In the summer of 1921 Man Ray sailed for France and it is claimed that he arrived there on the French national day, 14th July. Duchamp immediately introduced him to the Dada group in Paris. His friendship with Duchamp lasted for the rest of his life. To his surprise, Man Ray discovered that, apart from Duchamp, there were no artists in the group which consisted exclusively of poets and writers. Among these was the ever energetic André Breton who immediately realized that he could make use of Man Ray, asking him to take photographs for his magazine Littérature. Since Man Ray received no payment for the work he asked André Breton to publish reproductions of the works of art that he had brought with him from the USA. The portraits that Man Ray took of poets and writers for Breton’s magazine immediately aroused interest in artistic and literary circles in Paris. In this way he rapidly became a name and got to know many of the famous personalities in Paris. His fellow American Gertrud Stein introduced him both to Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. She was later to write: “Man Ray is Man Ray is Man Ray is Man Ray”. In order to improve his finances he started to photograph other artists and their work.

It was Tristan Tzara, the monocled poet and one of the founders of dada who introduced him to the possibility of creating photograms. These were photographic images produced without the use of a camera by placing an object on light-sensitive paper and exposing it to the light. The photograph was then developed and fixed in the usual way. This particular type of photograph has several names: “photogenic drawings” or “Schadographs” after the artist Christian Schad who also produced Photograms. Even the famous Hungarian Laszlo Moholy-Nagy produced photograms. All of these pictures, regardless of their author, are termed photograms. But Man Ray’s Rayographs are certainly the most famous of this type of photography. No less a celebrity than Jean Cocteau wrote appreciatively in “An open letter to monsieur Man Ray, American photographer” in Les Feuilles libres: “Your images . are the object itself. They are not photographed through the lense of a camera but are produced by a poetic hand directly inserted between the light and the light-sensitive paper.” Cocteau wrote this enthusiastic report after viewing Man Ray’s Rayographs. Cocteau’s article led to Man Ray receiving even more notice in Paris. Cocteau’s text also became known in New York and the Americans began to wonder whom this unknown compatriot was. Man Ray’s Rayographs were then published in Adventure, in Der Sturm The Broom and, as a whole spread in Vanity Fair. The poet Tristan Tzara also admired his photographs produced without a camera. Together with Man Ray he produced a portfolio of twelve images in a limited edition. This was entitled Les Champs Délicieux and had an introduction by Tzara.

Man Ray began to earn so much money from his photographs that he was able to rent a studio and darkroom in Montparnasse. Previously he had taken his photographs during the day and developed the material in the bath at his hotel at night. In his autobiography he relates how he visited the fashion designer Paul Poiret and showed him his photographs. Poiret was interested by what he saw and was keen to have his fashions photographed in this new manner. Man Ray’s imaginative approach to photography was admirably suited to the world of fashion and his fashion pictures were noticed both by the couturiers and by the fashion magazines. As a sought-after fashion and portrait photographer he could charge large fees and, in order to be able to work without being disturbed, he rented a second studio for his painting. He also hired assistants, many of whom later became famous names in photography.

It was in the mid 1920s that he discovered the ageing photographer Eugène Atget, who also lived on Rue Campagne-Première. Man Ray was passing Atget’s home when he saw photographs in special frames exposed on photosensitive paper. This was a technique that was used by photographers in the 19th century. Man Ray rang the bell and asked Atget if he could buy some pictures for the surrealists’ magazine. This met with approval but Atget did not want his name in the magazine. A year or two earlier André Breton had published the “Manifeste du surréalism” in which, inspired by the writings of Siegmund Freud, he started systematically to study dreams. Like dada, surrealism started as a literary movement and, apart from Man Ray, very few artists were invited to take part. Man Ray’s photograms were felt to fit the new ideal very well, being reminiscent of the automatic writing of the surrealists. Breton also considered that Man Ray’s early pictures anticipated surrealism. In spite of the fact that Man Ray was closely allied both with dada and with surrealism and that he took part in their respective events and published pictures in their magazines, he never sought membership of either of the groups.

American women visiting Paris with contacts in the world of fashion sought out Man Ray to be photographed in the latest creations of haute couture. Men wanted their portraits taken too and among those who sat for him were such famous names as Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, Virginia Woolf, Henry Miller, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce and Elsa Schiaparelli. The women that Man Ray mixed with appear with all the independence that they could muster in his portraits. There we find Kiki de Montparnasse, whose reputed beauty at the time seems to have suited an era different from our own.

Man Ray’s studio became something of a centre for young people interested in photography in Paris. One person who came to the studio in the early 1920s was Berenice Abbott whose acquaintance Man Ray had made prior to going to Paris. Abbott had come to Paris to study sculpture and she worked as an assistant to Man Ray to finance her studies. But she became more and more interested in photography. Man Ray introduced her to Eugène Atget and she made some exquisite portraits of the old photographer. Atget never saw the photographs since he died only a few days after the session. Berenice Abbott organised a search for photographs by Atget and, after much labour, she discovered many positives and negatives. She managed to purchase these and took them with her to the USA where they are now part of the collections of the Museum of Modern Art. Atget’s photographs appear in other collections, including that of the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. Inspired by Atget’s photographs of Paris, Berenice Abbott later started to photograph New York. She became one of the finest interpreters of that city and she passed on much of her expertise to a young photographer named Walker Evans. He later photographed people on the New York subway and was an important collaborator on the FSA (Farm Security Administration) project that documented how Americans lived during the Depression in connection to a Federal reform.

The young model Lee Miller who worked for both Arnold Genthe and Edward Steichen in New York, contacted Man Ray. She, too, became one of his assistants and was also his mistress for a number of years. If history is to be believed, it was during Ray’s collaboration with Lee Miller that he began to interest himself in the Sabattier effect in photography; or solarization as it is also known. On one occasion Lee Miller felt a mouse running over her foot. She opened the darkroom door and the light streamed in onto the photographic paper which was in a chemical bath half exposed. From this involuntary exposure Man Ray discovered that the dark and medium tones remained positive while the light areas became dark with only a contour around what had formerly been light surfaces. In the same way that he had formerly worked with the photogram he now seized on the Sabattier effect. Several of the studies that he later made of Meret Oppenheim, for example, made use of this technique which gave the pictures a highly personal character. There are really no basic rules as to how the Sabattier effect is to be achieved but each new picture is an experiment.

Lee Miller left Man Ray after a number of years and in his grief he produced his “Objet Indestructible”, a metronome whose pendulum carries a photograph of one of her eyes. During the Second World War, Lee Miller worked as a photographer with the allied troops. About 1930 Bill Brandt, an Englishman born in Germany, came to work as assistant at the Rue Campagne Première. Brandt’s later work varied between narrative reportage and surrealist images. These latter, certainly inspired by Man Ray, appear most strongly in the book Perspectives of Nudes which Brandt worked on from the year after the end of the war right up to 1964 when it was published. With his pictures from the strikes in the interwar years and from the Blitz, Brandt became one of Britain’s leading photographers.

In 1940 Man Ray left Paris in the company of Salvador Dali and his wife Gala. They arrived in New York on a boat from Lisbon. Man Ray spent a brief time with his sister before travelling by car across the continent to Los Angeles in the company of a tie salesman. He had difficulty in settling down in the USA but in due course he produced a series of portraits of famous actresses and actors at his new studio in Hollywood. His thoughts strayed constantly to Paris and to everything that he had been obliged to leave behind him when he fled. In 1944 he produced an album of drawings, texts and photographs to which he gave the title “Objects of My Affection”. The content of the album relates powerfully to his depressed mental state at the time. This loose-leaf album is now in the collections of Moderna Museet.

In 1947 Man Ray returned briefly to Paris to take charge of his remaining possessions and he found that quite a lot of his property had avoided being stolen during or after the war. It was not until some time in the 1950s that he returned to Paris for good. He rented a studio on the Rue Ferou and during the last part of his life he concentrated on painting and making objects as well as on producing new photographs from the old negatives.