When am I?

History is constantly under revision, of course; that’s why it’s so difficult to make a clear judgement on whether this or that was more or less contemporary than something else. Often, it’s history itself that does this – with hindsight.

This what makes plunging into the contemporary so difficult. It’s exciting and challenging, of course, but on closer consideration it can also be difficult to see the trees for the wood, so as to speak. To find your own path and the paths of others. To venture boldly into uncharted territory. It’s so easy to go astray, and you need something to navigate with.

Complex descriptions of the contemporary

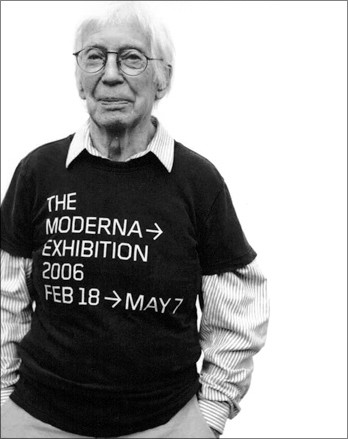

It was of course flattering when we – Pia Kristoffersson (on the selection committee only), Magdalena Malm and John Peter Nilsson – were charged with making the selections for The Moderna Exhibition 2006. But where were we to begin?

The concept of contemporary art – the art of the now – has a specific derivation. In the early 1960s, the artistic community began to question the notion of “modern art”. To be modern does, of course, mean to exist in the now, but the concept had taken on other meanings associated with modernism. Modern art was part of a cultural and social avant garde whose task was to pave the way for a new, better and more beautiful world. The avant garde were, as the name suggests, ahead of their times and ahead of society at large.

This is why our selections for the exhibition had as a matter of course to include artists who had made their breakthrough from the 1960s and onwards. We also wanted to achieve a broad overview of exhibitions past and present in Sweden. As part of our preparatory work, we sent a questionnaire to virtually every museum, gallery, artists’ association and independent curator in the country, requesting information on events they had staged in the past five years.

The result was astonishing. Artistic life in Sweden is extremely rich. But it soon struck us that that this artistic life is also highly heterogeneous – it’s impossible to argue that there is any single trend that has dominated this decade.

But through our discussions, research and meetings with artists, a number of clear lines eventually began to emerge. One important departure was the New Reality Mix art event in Stockholm in 1994, where a number of new concepts saw the light of day. We wanted to examine the relationship artists now have with the concepts of reality, sampling and the expansion of art into the social space. If cross-pollination between different aesthetic fields was originally a statement in itself, it has now become a method. A great deal of art in the 1980s and 1990s in particular was aimed at revealing, discussing and deconstructing social and cultural structures. That’s still true. But if, for example, a female artist discusses her identity these days, she can often do so without carrying the entire weight of womanhood on her shoulders. There is often a more personal touch, the artist discusses the world on the basis of her own experience. Art has, quite simply, become more personal.

But not in the way that, for example, Ulf Linde and Konstnärsbolaget had in mind, particularly during the 1970s as they aimed to eliminate anything that could be characterised as impersonal. The hallmark of quality was that it should be possible to discern the fingerprint of the artist in his or her work.

In our selections for The Moderna Exhibition 2006 we have noted the relationship between the individual and the surrounding world. These days, this is highly complex. It is neither structurally impersonal nor egocentrically personal – it’s both. This can be seen, for example, in the extraordinary success of the reality shows. The participants play themselves and their roles, both at the same time. Personal identity becomes a fictitious character and the TV scripts write themselves as the characters develop.

In the same way, the boundary between private and public ownership and influence in society has become diffuse. State-owned enterprises are obliged to adapt to the free market, just as private companies are obliged to adapt to norms laid down by the state. The result of this is that politicians can act as corporate executives and the executives as political ideologues. But when am I a citizen? When am I a consumer?

The Moderna Exhibition 2006 is designed as a sort of transition between different interpretations and translations of a world that is becoming increasingly intrusive. It follows a route in which islands of artistry, and works of art in particular, are presented as chapters in the story of our times. We could of course have chosen a completely different approach and, for example, focused on the artists whose work was most to our taste, without taking account of the relationships between them. But we chose these 49 artists, of between 28 and 99 years of age, since they complement each other in this story – just one of many – of the contemporary.

To emphasise just how difficult it is to describe the contemporary, we asked the editors of Glänta magazine to interpret the concept. What is it? And, to place the exhibition in its context within art history, we asked Annika Öhrner to interpret the period 2000-2005, using the late 1980s as her point of departure. Their contributions demonstrate that you cannot nail down an era now in progress with any degree of clarity. Thankfully.

Our story

By placing some of the works outside the exhibition halls themselves we want to emphasise the fact that a good deal of contemporary art is intended to confound the expectations of the beholder. Jonas Dahlberg’s CCTV cameras in the museum toilets expose our most private necessities. But if these are so pressing that we go ahead anyway, we find that we have been deceived. We believe Saskia Holmkvist’s video projection to be an in-depth interview with the artist until we discover that it is entirely staged. Magnus Thierfelder destabilises the functionality of the museum itself using a contrived water leak (at the time of writing we don’t know whether this will be technically possible). Annika von Hausswolff covers one entire wall of the Museum corridor with a curtain. The textile reminds us of underwear, and the public space takes on a slightly unsettling, intimate character.

Make your way to the Stockholm suburb of Hökarangen to visit Konsthall C. This gallery is a work of conceptual art by Per Hasselberg which examines the social ambitions of the “Million Programme” (the Swedish state’s massive housing construction programme of the 1960s and 1970s) to build away social injustice and create collective environments for personal encounters. This gallery is linked with the introduction to the exhibition. Immediately we find Anna Wessman’s installation commenting on why the most people in our democracy don’t speak out on social injustice. Elis Eriksson explicitly criticises care of the elderly, and since 1994, Magnus Bärtås has collected newspaper portraits of and comments from the socially excluded.

The eyes contributed by Magnus Wallin are filled with possibility and impossibility, staring their challenge at us, while a black preacher thunders his fury over the racial divide in a film by Mats Hjelm. Annika Eriksson’s filmed street scenes document how individuals and groups use the public space in different ways, and in Ann Böttcher’s painstaking drawings each tree emerges with a unique identity, filled with its own stories. An apartment is cleared in a video by Johanna Billing. A group of people with no relation to each other help out. Do the political ideas of community of the 1960s and 1970s still retain any validity? Felix Gmelin’s reworked videos from that era on sex education for the visually impaired place the views we now hold on the topic in contrast with those of that time.

A TV documentary about the UNA bomber is reinterpreted by Ola Pehrson and exposes today’s media-borne reality, something that Dorinel Marc and Monika Marklinger also bring to the fore. Marc presents portraits of media scapegoats borrowed from another artist, and in Marklinger’s installation, political slogans are mixed with a sort of media noise. Can we get behind the headlines? Is reality already defined by the power of the media? Have the clichés taken control? Marianne Lindberg De Geer’s Ghanaian dolls painted on landscapes bought at flea markets create a secretive, impenetrable world. By contrast, Ola Åstrand’s cartoon-like, twisted faces scream of their inner sorrows.

Karin Mamma Andersson’s paintings depict her own world through snapshots of time and space. When am I myself? If you enter Jacob Dahlgren’s room-in-a-room consisting of thousands of hanging silk ribbons, you meet – yourself. Per Enoksson connects his own traditions of the Same people to international iconography, and Sirous Namazi uses minimalist methods to create a fruit cart for a market stall. Ambiguity is explicit in two videos by Loulou Cherinet in which she compares similar places in Sweden and Ethiopia. Ylva Ogland paints torn-up photographs of herself as a child, naked and exposed. Johan Thurfjell’s noticeboard bears the traces of earlier public exhortations, but is now transformed into a private greeting of love. How do I come into existence in the expectations of others?

On the level of aesthetic ideas, Gunilla Klingberg’s installation conveys how the euphoria of the consumer society can be compared with the New Age movement. Can money buy happiness? Fia-Stina Sandlund interviews Panos, the swimsuit king who owns the rights to the Miss Sweden competition. Their conversation reveals a struggle between the artist and the entrepreneur, both of whom are using their own identities as a brand. By intermingling the imagery of advertising and terrorism, Annika Larsson’s video shows the dependence of both on the aesthetics and impact of the mass media. In Henrik Andersson’s video we see a line of text from a German text message service which is delivering a literal automatic translation of the Swedish Liberal Party’s immigration policy from Swedish into German, but with considerable difficulty.

Employing the same motif again and again but using differing techniques, Cecilia Edefalk highlights the importance of interpretation and translation in the creation of meaning. Is it possible to say that one image is more true than another? Andreas Eriksson, too, shifts perceptions. His castings of various non-electrical light sources pose intricate, almost existential questions. It is with light that we see, but how and when do we see what, as dictated by the light source?

In Christian Andersson’s installation, a brick flies out from a hole in the wall in what looks like a filmed sequence. This is an illusion that metaphorically exposes our hopelessly media-dominated world. Are Tomas Pontén and Rebecka Hemse, actors at the Royal Dramatic Theatre, playing themselves or are they following a script in Miriam Bäckström’s 70-minute film? Do the science fiction writers’ stories of supernatural metaphysical phenomena come across as credible in Tova Mozard’s videos? Can we be sure that light therapy and the audio loop that assures us that we are beautiful and wonderful actually change us? We so desperately want to believe in illusions, something that Juan Pedro Fabra connects with warfare. In an enigmatic and unsettling way his video piece conveys the idea of seeing without being seen.

Jenny Magnusson’s transformations of simple everyday materials render their abstract and anonymous origin into something personal. What are the sources of creativity? Jan Håfström returns to the drawings he did as a child and recreates a fantasy world that can be seen both as a metaphor for the artist himself and as an image of the role of men in our times. Torsten Andersson, too, revisits a decisive event in his life. His paintings analyse concepts like language and reality, both in painting and in an intellectual sense.

Private and public experiences are intermingled in our everyday lives amid a limitless stream of consciousness. In Lisa Jeannin’s videos, you enter a world in which the boundaries between your own life and extraordinary fantasies seem to have been erased. But the storybook world of fantasy can also be used to raise moral and ethical questions. Nathalie Djurberg’s animated clay figures reveal the bizarre aspects of gluttony. Oskar Korsár’s drawings are partly autobiographical chamber dramas about the hilarity of everyday life, while Camilla Carlsson’s wall of postcards showing destinations she longs to see but has never visited poses the question of whether dreams of longing are not in fact sometimes more real than reality itself. Does our literal presence in reality need to be turned upside down? In the Ride 1 Ferris wheel, you can sense how that might be.

Another harrowing experience is to enter Matti Kallionen’s world of shadows. His labyrinth-like installation both amplifies and destabilises your sense of presence. Is it this that Jonas Nobel means when he says that escapism is the only way out?

The Moderna Exhibition 2006

On June 27, 1983, Andy Warhol was talking to Pat Hackett on the phone: “But then, since the sixties, after years and years and more ‘people’ in the news, you still don’t know anything more about people. Maybe you know more, but you don’t know better. Like you live with someone and not have any idea, either. So what good does all this information do you?” (1)

Ten years later, the Spanish Philosopher Rafael Argullol tells his colleague Eugenio Trías in his book of dialogues El cansancio de Occidente why it is so difficult to meet other people: “Passivity is the hallmark of humans today. And it’s clear: if people are turned into spectators and robbed of any possibility of influence, this gives rise to a passive being. But all this, of course, takes place under the guise of its opposite. All maner of pseudo-events go on amid a stream of constant activity; activity that reinforces the passive, an uninterrupted motion that fades into immobility. We speak of all the stress and hecticness in our society, but the final impression is of a pursuit of emptiness.” (2)

Warhol’s and Argullol’s views hold true today, even for us in Sweden. The growth of communications technology in particular has changed our view of ourselves and the world around us. This applies in Sweden to the same degree as it does in other countries (at least in the wealthier parts of the world). The global village has shrunk our world and at the same time expanded it. Through technology, we approach what used to be the periphery, something which in modern art has essentially come to mean everywhere apart from Paris and New York.

Globalisation is indistinguishable from our media-borne experience of the world in which news, fictional accounts and private testimonies from different parts of the planet all jostle for space. Geographies have broken down. This is why we have to find tools to navigate our way through this new reality. One useful tool is personal experience, but this is garnered continuously and sometimes randomly on the journey through life. It does not arise exclusively from set definitions of who you are or where you come from. And so the question is no longer “who am I?” Instead, we suggest “when am I?”

(1) The Andy Warhol Diaries, edited by Pat Hackett, Simon & Schuster, London, 1989.

(2) Rafael Argullol, Eugenio Trías, El cansancio de Occidente, Destino, Barcelona, 1993.

Text: Magdalena Malm, John Peter Nilsson