Lotte Laserstein, Self-Portrait in the Studio on Friedrichsruher Straße, ca 1927 Photo: Lotte-Laserstein-Archiv Krausse, Berlin ©Lotte Laserstein Bildupphovsrätt 2023

About the works

Lady in a Fur Coat (The Gallerist Signe Schultz), 1941

The gallerist Signe Schultz (1894-1960) is portrayed directly from the front, sitting in an armchair with her legs crossed. She is wearing a coat and beret and looks like she is just about to go somewhere. Under the close-fitting, open fur coat, we see an elegant crimson dress. With one hand in her coat pocket and the other hanging over the armrest, Signe Schultz looks slightly tense and watchful. Her gaze does not seek the observer, but remains reservedly introverted. The artworks in the room tell of the environment she is in. With great deftness, Laserstein evokes the soft brown structure of the fur and emphasizes Signe’s jewelry: ring, bracelet, and earrings. The drawings that hang on the wall behind the art dealer form a grid that highlights her figure and frames her head. Here sits a self-confident, ambitious businesswoman about to leave her gallery.

From 1928, Signe Schultz and her sister Alice Lagerbjelke ran Galerie Moderne at Nybrokajen in Stockholm. Because of an invitation to exhibit her work in the Swedish capital, Lotte Laserstein had left Germany in 1937, with many of her most important works in her luggage. It would turn out that the sisters’ exhibition invitation would save Laserstein’s life.

The Gedin Brothers, 1942

Hans and Per Gedin, who are fifteen and fourteen years old here, both give an inquisitive impression. The brothers had fled Berlin with their parents and arrived in Sweden in April of 1938, a couple of months after Laserstein. Now, four years later, the young men sit relaxed and focused, each on his own task: Hans reads a book while Per, who would later become a publisher, holds a model airplane in his hands and looks with interest out of the picture. Per has said that his brother Hans, who later became a researcher, was the more introverted of them, while he was the more extroverted–qualities that Laserstein observed and captured.

The young men sit in their boyhood room on Linnégatan in Stockholm, where the family moved after emigrating. On the wall behind them is a map of northern Europe, where Scandinavia and Sweden, their new homeland, are in the center. Per remembers Lotte Laserstein as a friendly but fairly decisive person, and how boring it was to need to sit still for so long; it took several sittings before the painting was finished. In his autobiography “A Publisher’s Life” (1999), Per, subsequently Per I. Gedin, tells how difficult it was in the beginning for the two brothers to find their way in Swedish society, even though they had grown up in a bilingual household and spoke Swedish fluently. He also discusses the widespread anti-Semitism they encountered.

In contrast to “The Emigrant”, the double portrait “The Gedin Brothers” communicates a hope that the young generation of refugees, with their inherent openness and inquisitiveness, in the future might be able to contribute to a better world–even if the war, when the portrait was painted, raged throughout Europe.

Self portrait before ‘Evening Over Potsdam’, 1950

Lotte Laserstein here paints herself before one of her most important works from the Berlin years, “Evening Over Potsdam”, from 1930. Now, twenty years later in Stockholm, she stands dressed in a painting coat before her easel. Laserstein is about to paint the self-portrait we are looking at, which is identical to the picture she sees in the mirror. Instead of looking forward in time, she looks back, perhaps to be better able to understand herself in the present day. The artist’s gaze out of the picture and into the mirror is serious and pensive.

When “Evening Over Potsdam” was painted, Laserstein was at the beginning of her career, which seemed like it would progress straight as an arrow–but that instead was abruptly halted with the Nazis’ persecution of the Jews and the subsequent necessary emigration. Laserstein survived here, later living twelve years in safety in Sweden. She has yet again tried to build a life and a career from the ground up, now under completely different conditions. Time has passed, she is older, and she hasn’t seen the friends who were the models for the painting since she left Germany. Even if the circumstances have changed, there may be some parallels between the uncertainty that colors the mood in the earlier painting’s summer evening, where the future for Germany was unclear–and the artist’s own uncertain situation in the later portrait. Laserstein is still a painter here, but the hopefulness she exuded so recently as in her first self-portrait in Sweden, “Self-portrait at the Easel” (1938), is now overshadowed by the gloom that seems to weigh down her future.

The Painter and Madeleine at the Easel, 1947

One year after the end of the war, in 1946, Lotte Laserstein had regained contact with her old friend and favorite model, Traute Rose, from her time in Germany. After many years of forced silence, the two had begun writing letters to each other, and slowly, their friendship was revived. When Laserstein began the self-portrait “The Painter and Madeleine at the Easel” in 1947, it could be interpreted as the beginning of a dialogue with another important self-portrait she painted almost twenty years earlier in Berlin: “Me and My Model” (1929/1930). There, Traute Rose, wearing a thin gown, laid a gentle hand on Laserstein’s shoulder to examine the painting her friend was working on.

The portrait from 1947 resembles the portrait from 1929 in composition. Traute has, however, been replaced by Laserstein’s Swedish model Madeleine, who examines the painting on the easel while she braids her long hair. In both of the paintings, the artist, brush in hand, looks out of the picture and into a mirror, which coincides with the observer’s position and perspective. In this later painting, the artist Laserstein looks reflective and the situation radiates a certain gravity. If we find a hopeful, sensual energy in the earlier self-portrait from 1929/1930, here, we see all enthusiasm is lacking. Even the color palette is kept to muted brown and beige tones. As we assume from a painting that hangs behind Madeleine, the scene plays out before a wall. The painting, and perhaps even life in this period, seems to lack space. Even Madeleine, whose real name was Margareta Jaraczewsky, had emigrated from Berlin. She came to be Lotte Laserstein’s favorite Swedish model, including for many nude studies.

Evening Conversation, 1948

This work was created three years after the end of the war. In contrast to many of Lotte Laserstein’s works from this time, this is not a commissioned piece. The painting communicates an atmosphere of uncertainty. In a dark, tight space without visible windows or wider views, five people are in conversation. All look attentively at the man to the left in the picture, and seem to thoughtfully listen to him. The light that falls in from the right prompts dramatic light-and-shadow formations over the wall as well as over the participants, underscoring the seriousness of the gathering.

We know today who the people in the picture are, with the exception of the man who is standing. All were refugees from Nazi Germany; to the left sit the Sedermanns, to the right, the sculptor Walther Beyer with his wife Marianne. Muted tones in blue, gray, and brown underscore the gravity of the situation. The paint, applied here and there in a manner reminiscent of the brushwork in the painting “The Emigrant”, makes the figures slightly blurry and causes them to appear as representatives of people in an uncertain life situation rather than as portraits of individuals.

Here, Lotte Laserstein thematizes the question that many emigrants were faced with at the end of the Second World War. Should they remain, return, or move on? The observer is drawn into the circle of friends and finds themselves between Marianne Beyer on the right and Mr. Sedermann on the left.

The Émigré (Dr. Walter Lindenthal), 1941

Lotte Laserstein paints Walter Lindenthal (1886-1975) wearing a brown winter coat and a warm scarf. He is sitting directly facing the observer, a wool blanket over his lap to protect him from the cold. With his hands folded over a newspaper or book, Lindenthal stares before him with an inscrutable gaze. The background is a diffuse light gray, and the shadow suggests he is sitting against a wall, in a “non-place.” This is a person who is waiting for something, he is on the way to an unknown destination. Laserstein blurs Lindenthal’s eye area so that he appears more as a proxy for all who have been driven out, jerked from a safe existence, who wait in uncertainty–banished to their thoughts and memories. The painting’s muted, dark tones in brown and gray underscore the grave mental state of the emigrant.

In Stockholm in 1939, Laserstein came to know the lawyer Dr. Walter Lindenthal–twelve years her senior and also an emigrant from Berlin. Because he was Jewish, he had been removed from his position as lawyer on the City Council already in 1933. In Sweden, Lindenthal worked occasionally as a librarian, but he gradually became known as an esteemed translator of Swedish and Norwegian fiction into German. Through the late 1940s, he was also an editor at the Bermann-Fischer publishing company in Stockholm. Laserstein and Lindenthal, who shared the experiences of escape and exile, became very good friends over the years, and their friendship lasted throughout their lives. They socialized in Stockholm, but the friends also traveled to Ascona in Switzerland many times after the end of the war and even visited Israel together.

Self-portrait at the Easel, 1938

At Fulltofta estate in Skåne, where Laserstein found herself in the spring of 1938 to paint the portraits of the Trolle family, she also painted her first self-portrait in Sweden. Here, it is as if all worries have been whisked away. Laserstein depicts herself for the first and only time in full, as a dynamic and decisive artist at her easel. Under the open white painter’s coat, she is wearing a red cardigan, a black-and-white patterned scarf, and black pants. We meet an attractive and confident woman who looks straight out of the picture with a scrutinizing yet simultaneously welcoming gaze. With one hand resting in her coat pocket, she raises the brush in the air with the other, as if she is just about to measure the model in front of her before continuing with the painting on the easel. That Laserstein, who is right-handed, lifts her left hand reveals that we are looking at a reflection as she is observing herself in a mirror in order to paint her own portrait.

Laserstein depicts herself before a light background that does not reveal anything about herself or where she is–an artistic approach she also then used in other paintings, particularly of refugees, to portray the uncertainty and homelessness of exile. Here, in her self-portrait, Laserstein instead emphasizes the attributes she needs as an artist: her easel, the hand with the brush, and her eye. In this way, the work is like an open invitation to portraiture from the artist herself. Here, Laserstein is in a phase of her life where she can finally continue to work as an artist. Under the given circumstances, she finds herself in the best possible place in existence.

Thines Ahlcrona-Ohlsén, 1939

The portrait of Thines Ahlcrona-Ohlsén (1894-1991) exudes more artistic freedom than many of Laserstein’s other projects. Ahlcrona-Ohlsén was a reform pedagogue who ran a preschool in her own home on Ehrensvärdsgatan near Värnhem in Malmö. Laserstein paints her standing in three-quarter profile, the teacher meeting the observer face to face with a watchful, calm gaze. With one hand in the pocket of her white coat and the other resting on her hip, she stands as steady as a rock. Laserstein captures an impressive confidence and strength, emphasized by Thines’ powerful hands and angular face, which is framed by her medium-length dark hair.

The two children that have been entrusted to the teacher stand to the left in the picture, protected at her side, quietly immersed in their own worlds. The red bureau with the old counting device on it, along with the maroon tones of the children’s clothes, make Thines look luminous in her white coat. The portrait is painted on cardboard, and in many places, Laserstein allows the unprimed surface to show through as if to underscore the preschool teacher’s sincerity, earthy warmth, and integrity.

We do not know today how Lotte Laserstein and Thines Ahlcrona-Ohlsén met, but it is possible that Thines took care of children from families whose portraits Laserstein painted in Malmö. The two became very close friends, and when Lotte decided to build a summer cottage on Öland in the 1950s, it was next to Thines and her husband Erik Ohlsén’s property.

Nora Bigner, 1938

Lotte Laserstein depicts the couple Folke and Nora Bigner, whom she (1938) got to know via Galerie Moderne. Nora, wife of the civil engineer and business leader, is painted in profile, sitting with her hands around a parasol, leaning slightly against one of the armrests of her seat. Nora’s friendly, slightly dreamy gaze is directed outside the picture and seems to invite us in as a conversation partner rather than as an observer. The unfolded Japan-inspired parasol behind Nora’s back frames her face and, in interplay with the white summer blouse adorned with two red flowers, gives her countenance a soft and playful expression that stands in appealing contrast to the portrait of her spouse, Folke. The portraits were presumably intended to hang next to each other.

Nora Bigner appears here as a representative of the modern, wealthy Swedish upper-class patrons of culture and the arts. She was also a socially-engaged individual who helped refugees arriving in Sweden in the 1930s and 1940s. In her family’s flat in Stockholm, Nora organized several exhibitions of Laserstein’s works to show her art to friends and acquaintances, in the hope this would result in commissions for Laserstein.

Nora and Folke Bigner appear in the portraits as warm and empathic people, and over time, Laserstein would develop a close friendship with the couple. She spent time with the Bigners at their summer cottage on Smådalarö and painted several portraits of family members.

Self-Portrait in the Studio on Friedrichsruher Straße, probably 1927

Lotte Laserstein graduated from the art academy in the spring of 1927. She had been training for five years. Now she had to make her mark as a painter in Berlin, an international hub of the arts. That summer she moved into her first personal studio. The attic space with wide windows on the western edge of the city center was to be her refuge for the next three years.

Her “Self-Portrait in the Studio on Friedrichsruher Strasse”, probably painted soon after she moved in, does not yet show her in the pose of a professional artist, which she adopted not much later in the paintings “In My Studio” and “Self-Portrait with a Cat”. In summer clothes, her head slightly tilted to one side, she seems a little skeptical as she gazes at the beholder and at the same time into a mirror. What will her future bring? Is she on the right path? The background can be seen as a metaphor: the panorama spread out below her is a huge construction site. Just as the metropolis is expanding, the painter is maturing and taking shape.

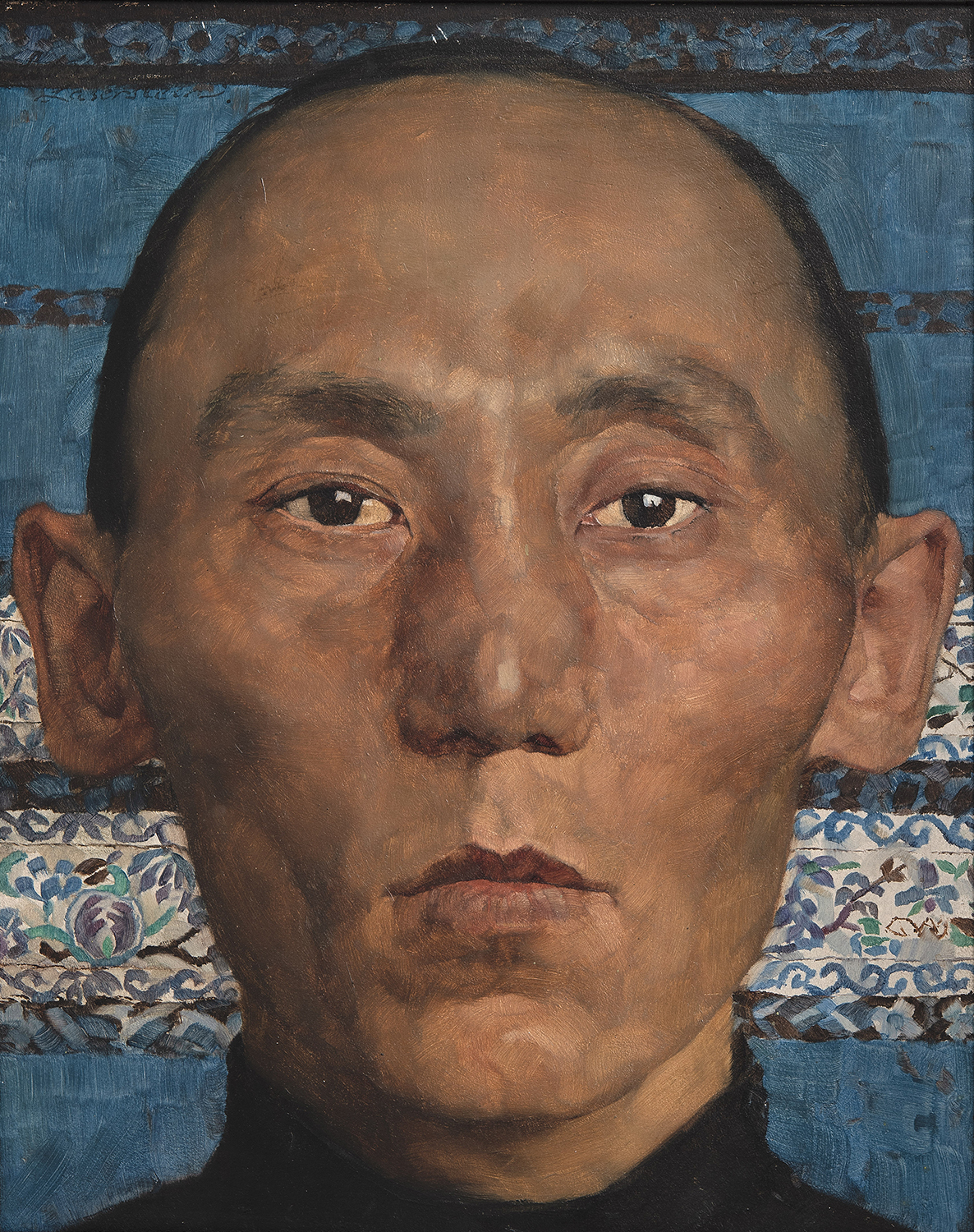

Man from Mongolia, 1927

Lotte Laserstein was confident about drawing on the repertoire of art history to reinterpret established visual conventions, but she was equally amenable to picking up formal codes from the imagery of her own day. A number of her compositions took their cue from photography, which flourished in the 1920s with so many illustrated magazines on the market hungry for input. As photographers competed for page space, they experimented with unfamiliar angles to create interesting images. One innovative device was the close-up, radically filling the frame with a face.

Laserstein borrowed this mode for her portrait “Man from Mongolia”. Although the artist has zoomed in on her model, challenging the viewer to walk up close to the small format, the sitter himself strangely keeps his distance. Although he seems to be looking straight at us, we cannot catch his eye. In fact, the longer we look into his face, the more the man seems to turn inward. It is this being at one with himself that lends him dignity and individuality. There is no fodder here for intrusive exoticism or arrogant stares. The fascination in this portrait derives from the impenetrable expression of the model with his powerful yet detached presence.

The sitter was recently identified. He was an actor named Mammey Terja-Basa who appeared in several feature films during the 1920s and earned a living as a model at the Berlin Art Academy.

Russian Girl with Compact, 1928

A young woman consults the mirror in her little powder compact to check that her fashionable bob is tidy. This painting of an unspectacular everyday gesture was Laserstein’s entry for a competition held in 1928 to find the best German portrait of a woman, which was being organized by the cosmetics manufacturer Elida and the German Association of Fine Artists. The work was shortlisted under the simple title “Portrait” (the artist obviously thought it inappropriate on this occasion to mention her model’s nationality), and it toured several German towns as part of a traveling exhibition, met by a flurry of press reviews that established the painter’s reputation beyond Berlin.

In choosing to depict a woman looking in a mirror, Laserstein was not only responding astutely to the set theme, but acknowledging a long tradition in art history. The artist captures this intimate act with both unpretentious nonchalance and painterly virtuosity. The velvet red contrasts effectively with the pale face and dark hair, while the blue of the compact and the soft puff held in carefully manicured fingers create a delightful highlight at the center of the painting.

Because of the way this picture is constructed, we are not simply looking at the woman looking at herself; we are looking with her. Our view of the back of her head in the mirror is almost the same as her view in the compact. Our observation is interwoven with that of the model, and this blending displaces the passive component typically entailed by the theme. In Laserstein’s mirror scene the protagonist is not the object of our gaze but plays her part as an active subject who is, at the same time, the object of her own gaze.

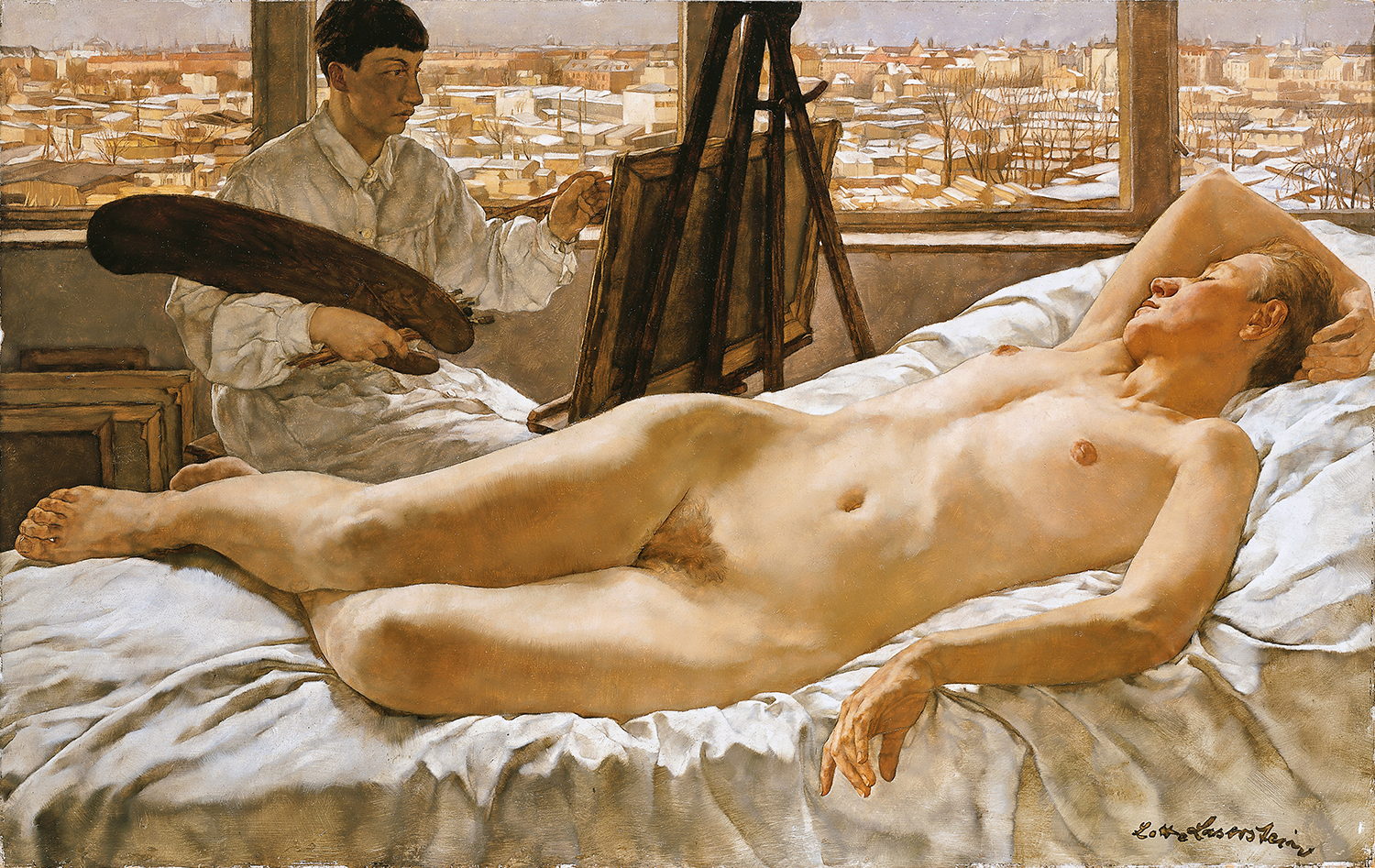

In My Studio, 1928

Well into the twentieth century, painting nudes was male territory. For women artists, the motif was seen as inappropriate. Laserstein, however, is not coy about placing a meticulously detailed female body center-stage in this self-portrait with model. She herself takes a back seat, obscured by the back-lighting effect, behind her slumbering friend. By positioning her model at the front, the painter once again demonstrates the vital role that Traute Rose played in her creative process.

Pale winter light falls into the studio through the wide panoramic window. Here above the roofs of the city, the painter and her model occupy a world of their own. Calm concentration and sensuality pervade the workaday scene.

But what is the artist actually painting? Is it really the nude model spread out before her, whom she must surely be seeing from the rear. If we look at the canvas on the easel, which Laserstein has significantly placed in the middle of her composition, it clearly cannot be the elongated wooden panel that we are looking at now. So this seemingly realistic glimpse into the studio is not an authentic reflection after all, but a sophisticated pictorial invention. As we contemplate the “reality” in the painted scene, we realize that the work has its own reality. We might wonder whether the artist ever painted a nude at all, but the narrative in this picture offers no answer. Only the painting hanging in front of us provides irrefutable evidence that she did. With “In My Studio” Laserstein is not only demonstrating her supreme command of this genre, but also succeeds in rendering a naked female body with confidence, utterly without voyeurism, and as if it were the most natural of themes.

I and My Model, 1929/30

Lotte Laserstein formulated the special significance of her model Traute Rose in paintings such as “In My Studio” and “At the Mirror”, but in the double portrait “I and My Model” she also visualizes the closeness of their companionship. This time in an undefined setting, Laserstein again shows herself at work surrounded by the things that constitute her personal universe: the canvas before her, the brush and palette, and at her shoulder her attractive friend, who steps up behind the painter to cast a glance at the work in progress. The gentle gesture of Traute’s resting hand and the whispering pose as she leans slightly forward, and even the sensuality she exudes in her chemise with its satin sheen, reflect iconographic conventions associated with the muse as a trope. But Laserstein deconstructs the tacit hierarchy usually inherent in the role of the muse by subtly guiding the viewer’s gaze along a pathway.

The artist stares assertively out of the frame, seeming hardly to notice her friend’s touch. She must be looking at a mirror, which is essential when painting a self-portrait. It is clear from the direction of her eyes, however, that she is not seeking her own image there but that of her friend standing behind her. This shift draws the optical sequence back toward the painting before us, or rather to the model, who picks up our gaze and deflects it forward by looking at the canvas where the artist is intent on reproducing what she sees in the mirror. Seeing and painting, then, are fused in a circuit that inextricably links the artist, the model, and the canvas.

Children with Handcart, 1932

In the 1930s Lotte Laserstein took her art students on annual excursions to the countryside. In 1932 they went to Neu St. Jürgen, a little village on the bog Teufelsmoor near Bremen, not far from the former artists’ colony Worpswede, where Paula Modersohn-Becker had lived. The painters from Berlin stayed in a simple guesthouse and hired children, elderly people in need of extra income and day laborers to come and sit for them in return for a decent payment.

Among these were the girl and boy lost in thought standing by a handcart containing a younger child. Inward looking, close together, and yet taking no notice of each other, this group of children display a melancholy. Only the rich velvet red of the sweater and the fidgety fists of the blond toddler animate the static composition in muted tones. Despite the low angle that lends the models a monumental quality, there is nothing heroic about these country children. They appear, rather, to be yielding to their destiny as they gaze across the brown heath. The light, dulled by dark clouds, reinforces the subdued atmosphere. There is also a reference to Christian iconography, for at first sight the upturned handle of the cart resembles a cross held piously by the boy with his back to the viewer.

Creative activities

Meeting art together with children is often an eye-opening experience! Our family activities encourage children and adults to experience art and be …

Creative activities

Meet the art!

Book a guided tour for your students, friends, colleagues or club. Experience an inspiring and dynamic environment, discover new perspectives and new …

Meet the art!

Welcome to Moderna Museet Malmö

Moderna Museet Malmö is located in the city centre of Malmö. Ten minutes walk from the Central station, five minutes walk from Gustav Adolfs torg …

Welcome to Moderna Museet Malmö