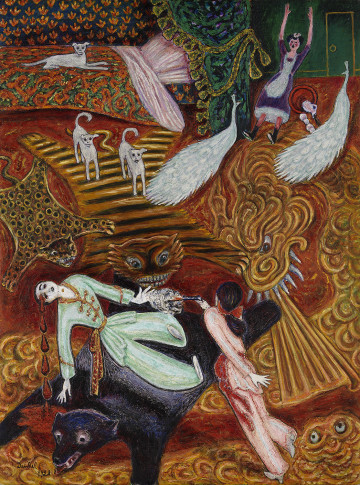

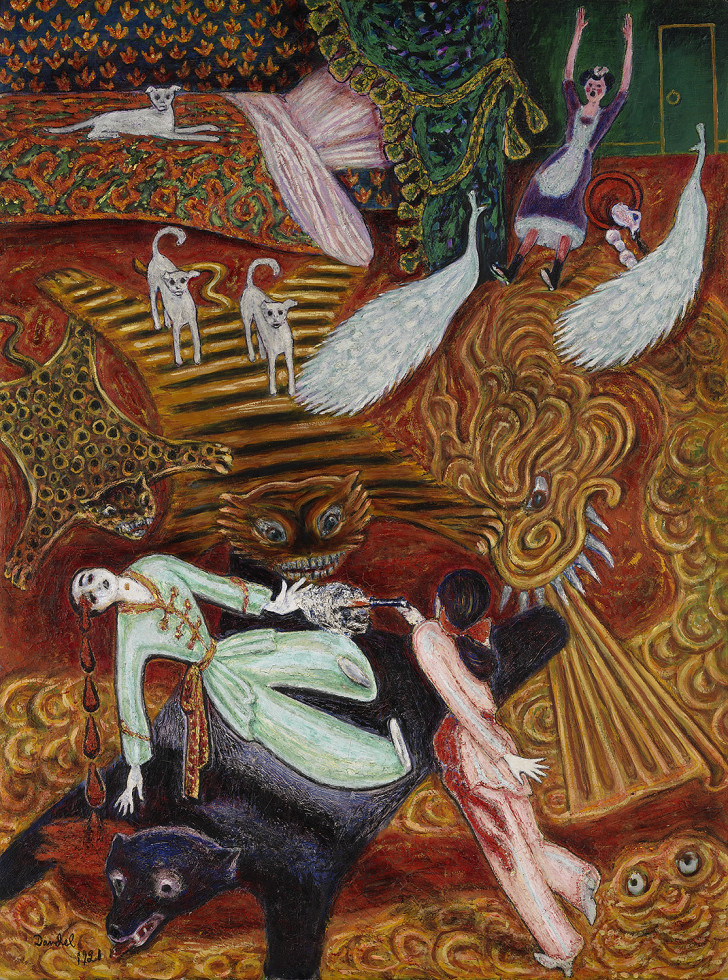

Nils Dardel, Crime of Passion , 1921

The Modern Age

The fleeting, ephemeral modern life gave rise to a special sensitivity and restless mobility, which was expressed in modernist art. Modernism was utopian. The avant-garde was constantly looking for what had never been seen, and new “isms” were born head to tail: cubism, futurism, rayonism. The new freedom of art came to symbolise the general freedom of the individual in the emerging democracies. Artists were no longer governed by the constraining rules of the academies but instead appeared as independent geniuses. In spite of its close relation to modern life in general, a lot of the art was striving for a purely aesthetic quality in the motifs, and some of the avant-garde artists worked out rigid formal doctrines.

Nils Dardel (1888–1943) had one foot in Swedish culture, but was also exceedingly international, in life and in art – he attained an unparalleled position in Swedish modernism.

Young radical Nordic artists, including Dardel very briefly, studied in the Paris studio of Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and the master thus came to have a great impact on Swedish modernism. Matisse included figurative elements, while maintaining that the purpose of a painting was to arouse joy through rhythmic arrangements of lines and colours.

Although influenced by international tendencies, Swedish modernism nevertheless had local characteristics, for instance a narrative urge – art should convey a story. In the recently industrialised and urbanised Sweden there was also a sense of nostalgia, allowing a mourning of the old world that had been lost.

Paris and Senlis

After a short sojourn at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, Nils Dardel went to Paris in 1910, a city where he would spend a large part of his life. Here, he was hurled into an intense whirlwind of bars and cafes, where artists and collectors had lively discussions about astonishing new styles of art. Dardel became friends with the German Wilhelm Udhe (1874–1947), who was the cubist Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) art dealer and the one who discovered the naivist Henri Rousseau (1844–1910).

Udhe took Dardel to the mediaeval city of Senlis, where the artist tried his hand at cubism in Girl with Iron Ball and Rue Ville de Paris in Senlis, that is, he reduced his visual impressions to simple geometric shapes in a subtle grey scale. But this was just a short flirtation. In the idyllic community northeast of Paris, Dardel also painted Funeral in Senlis, hinting at the narrative, almost naivist style for which he soon became known. This painting captures the life of a small French town. The shimmering colours are applied in dabs, and the white choirboys contrast with the mourners dressed in black.

Travels and drama

Dardel spent the summers in Sweden and in summer 1912, he met the future art collector Rolf de Maré (1888– 1964). They began a lifelong friendship, and de Maré was both Dardel’s mentor and supported him financially. When de Maré started the Ballets suédois in Paris in 1920 – a radical, multi-disciplinary dance company that toured – Dardel helped engage artists, poets and filmmakers in the company, thanks to his Paris contacts.

In 1914, the year the First World War broke out, the two friends travelled abroad. Dardel was fascinated in Spain by artists such as El Greco (1541–1614), whose painting The Burial of the Count of Orgaz inspired Dardel to create his famous work, The Dying Dandy, which he painted a couple of years later. In 1917, after a stay in Japan, Dardel travelled through Russia in the throes of the revolution, which he rendered in The Trans-Siberian Express. In fused visual impressions we experience both the outside of the train and the inside compartments with soldiers, as horse-drawn carriages are passing by. The light from a lantern cuts across several pictorial fields in a futurist manner.

The Dying Dandy

The years from 1918 and on hold a careful hope; the old world lay in ruins and a new one had to be built. The Wall Street Crash in 1929 put the hope out. During this period, Dardel found his unique style and produced his most famous works. He had tried various “isms”: symbolism, cubism and expressionism. Now, he took what he found useful from the rich assortment of styles and mixed it with impressions from his travels. The macabre, vibrantly colourful Crime of Passion is reminiscent of an Oriental carpet. The stories told are dramatic and seem to take place between dream and reality.

Dardel suffered from a serious heart disease and knew he would die fairly young, and he burned his candle at both ends. He abused alcohol and had romantic relationships with both men and women. This gave rise to gossip and myths, and to this day his art is often believed to be autobiographical. A pale, androgynous central figure in The Dying Dandy holds his hand on his heart, surrounded by mourners as though he were a Christ figure. The style is modern. The figures and coherent blue shape of the background co-exist on the flat surface. The colours play expressively with the complementary hues: blue against orange, red against green.

Dardel and the Beau Monde

Paris in the 1920s was a veritable free zone of acceptance for alternative lifestyles. For instance, homosexuality was not illegal as it was in Sweden until 1944. This Parisian liberty suited Dardel. In 1921, however, he married the young art student Thora Klinckowström (1899–1995). Soon after, their daughter Ingrid was born, and they began alternating the bustle of Paris with peaceful summers in the Swedish countryside.

Dardel drew portraits of the family, and the decade was a fairly stable period, with a permanent residence and studio in Montmartre. He received many commissions for portraits and his socialite portraits were highly acclaimed, not least for his ability to beautify his models.

The Domestics of Death

The global economic turmoil impacted on Europe in the early 1930s. In Paris, the cost of living went up and pleasures became expensive – the roaring 1920s gave way to a more sombre atmosphere. Many Scandinavians left Paris, but Dardel stayed behind. He moved to a cheaper apartment and got divorced. His health deteriorated, his heart condition got worse. These intimations of death are reflected in paintings such as The Domestics of Death – À ta santé, Nils.

Gone is the myriad of odd figures in an unspecific visual space; instead, we find an intricate system of gazes. The three undertakers in their traditional garb fill the surface, staring straight at us and raising their glasses. But our gaze is also that of Dardel, who appears in the mirror behind the three men – we are toasting death in his company. Dardel travels in the 1930s included a trip to Tunisia, where he made studies of the inhabitants.

The last journeys

Dardel’s largest exhibition so far took place in 1939 at Liljevalchs konsthall in Stockholm and was a great success with audience and critics alike. Dardel left Sweden for one final trip to New York in the company of his latest love interest, the Swedish-American writer Edita Morris (1902–1988). New York was a refuge during the war for artists such as the surrealists Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) and Max Ernst (1891–1976). But Dardel did not immerse himself in New York as he had done in Paris; instead, he travelled on to Mexico and Guatemala, where he produced some 40 watercolour studies of indigenous peoples in a few months. The critique was ambivalent when they were exhibited, at Nationalmuseum and The Gothenburg Museum of Art among other venues, after Dardel’s death. But the Swedish populace embraced the Latin-American watercolours and the portfolio titled Exotic became immensely popular.

Dardel and de Maré

One of Sweden’s greatest and most discerning collectors of modern art was Rolf de Maré. He came from a wealthy von Hallwyl family and became proprietor of the family’s summer residence Hildesborg Palace outside Landskrona in 1912. But de Maré was passionate about art and began to build a collection just before the First World War.

Nils Dardel was invaluable to this project, with his knowledge and network of contacts, and introduced de Maré to modern Parisian painting. Initially, Dardel would mediate and negotiate deals, but Rolf de Maré soon became friends with Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque (1882–1963) and Fernand Léger (1881–1955) and could buy works directly from artists. Works from de Maré’s collection have been donated and sold to Moderna Museet successively, and in 1966 large parts of the collection were bequeathed to the Museum.