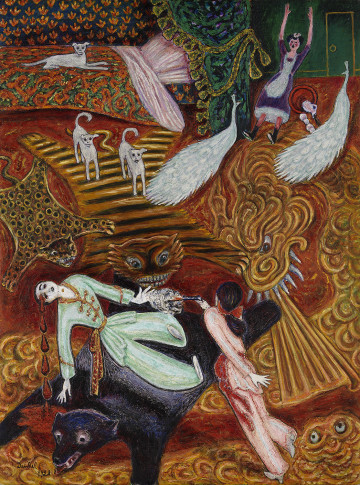

Nils and Thora Dardel next to ”Crime passionel” in the studio at Rue Lepic, 1921 © Riksarkivet, Thora Dardel Hamiltons arkiv. Photo: Okänd

The Democratic Dandy

Text: John Peter Nilsson, curator

Nils and Thora Dardel, Paris, circa 1920.

© Riksarkivet, Thora Dardel Hamiltons arkiv

I suspect that his character stood in the way of his artistic career – for many years, some critics considered him to be a superficial and trite artist. Even worse were the many attacks on him as a person, relating to his ambiguous sexuality. Dardel was deeply hurt by the criticism, even though he usually dismissed it with his sharp and witty tongue.

His reputation improved from the 1920s, when he began painting more society portraits. Like Andy Warhol, his paintings of famous people tended to make his models slightly more beautiful than they were in real life. In Dardel’s “aesthetic beauty parlour”, as his artist colleagues teasingly called his studio, the author Hjalmar Bergman’s waistline shrank and his neck grew longer, for instance. He was a masterly portrait painter – especially when it came to the realistic studies he executed on his prolific and long travels around the world, reproductions of which later adorned the walls in many homes. His countless self-portraits (including the more or less disguised versions) are also sensitively painted or drawn. These works show him as sensitive and fragile, and it is this very discrepancy between lifestyle and self-portraits that have nourished the myth of Nils Dardel, the dandy.

The Dandy is a concept with roots in the 18th-century British aristocracy and refers to the men who returned home after their more or less obligatory educational journey to Italy, the so-called Grand Tour. Back home, these dandies would display their acquired habits and new fashions, and when they ranted about their adventures, they would be ridiculed and called macaroni, as Roger Cook writes in his essay “Democratic Dandyism: Aesthetics and the Political Cultivation of Sens”. As an antithesis, Cook continues, Beau Brummell (1778–1840) developed the macaroni into a form of proto-dandy, with a novel, extremely elegantly-tailored fashion that exudes an air of nonchalance. Instead of the aristocratic macaroni’s exaggerated opulence, Brummell’s dandy wanted to create ephemeral nuances of terse finesse that were undetectable to the uninitiated.

The democratisation of the dandy took place, according to Cook, alongside the gradual change of class society in the 19th century. The emergence of a middle class made it possible for individuals to create their own identities, independent of the feudal class system. Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) developed an aesthetic that revealed the possibility of shaping one’s own image. In his book The Soul of Man under Socialism (1891), Wilde writes: “The true perfection of man lies not in what man has, but in what man is.” Thus, Wilde sows a seed to what has come to characterise the entire 20th century – the freedom to determine who we want to be.

Let us return to Nils Dardel and the previous century. He came from an aristocratic background, and the Dardel family was comfortably off, without being exactly wealthy. In the early 1900s, he was living in Uppsala, where he mixed with the students who celebrated old traditions, blue blood and the fatherland. Even if Dardel kept aloof, he began consciously to construct his own self-image. Unlike Oscar Wilde, however, who strove to “assert himself, get to know his own personality and dare to live in accordance with this knowledge,” since it was “the only truly viable road to a more truthful life,” Nils Dardel disguised his real self, writes Erik Näslund in his comprehensive biography, Dardel (1988). After Dardel had found his highly eccentric style in the late-1910s – described by the art critic Ragnar Josephson as “Dardelism” – nearly all his subsequent works appear to be autobiographical. But how much do they actually reveal? It is as though the masked self gave him the freedom to mix reality with imagination. His works originate in a first-hand experience, but the event is exaggerated and warped the moment Dardel applies brush to canvas. The paintings are like dream visions.

It is as though Dardel did not want to see reality as it was, and he was at his happiest in front of his easel. Here, he could let his associations run wild. The world as it was did not interest him. Nevertheless, Dardel did accompany Rolf de Maré on one of his first round-the-world trips during the First World War. And during the Second World War, he was in New York and visited South and Central America periodically together with Edita Morris, his loving companion since the formal annulment of his marriage with Thora Dardel in 1934. In both cases, however, the travels seem to have been a way of turning a blind eye to the killings and miseries of war.

Did Dardel turn away because he himself lived so close to death? In 1905, aged only 17, he contracted scarlet fever, resulting in a chronic heart condition (which eventually caused his death). Several of his biographers claim that this heart disease had a strong impact on the rest of his life. He expected that he would die young, and consequently had a hectic social calendar periodically, with heavy drinking, as though every moment might be his last.

This conflict between outer and inner reality is characteristic of Dardel’s oeuvre from the period when he found his own style until his death. His works are quirky, a seemingly banal and innocuous trait can suddenly shift into its diametrical opposite. Seriousness and irony go hand in hand and many of his works have several parallel storylines. Thus, one individual painting can captivate us for very, very long. This parallelism also entails that his “narratives” have multiple entry and exit points. This ambiguity exists equally in his person and his works. His is a dual nature that attracts and is attracted by both men and women. The moment I think I have grasped the meaning of a work, it once more evades my interpretation. “Why not the other way round!” as Nils Dardel would say.

Karl Asplund called him a “man of opposites”. Could this ambiguity stem from a mindset typical of the early 20th century? I would claim that Nils Dardel is a modern artist – albeit not unequivocally a modernist. He is torn not only between an inner and outer reality, but also between tradition and regeneration. He never grapples with modernist formal experiments, with the exception of the period immediately after his time at the Academy, when he belonged to the group De Åtta (The Eight). On the contrary, his style is more reminiscent of a mixture of naivism and late-19th century symbolism. His sensitivity can also be interpreted as a status marker, according to Karin Johannisson, of the kind used by the upper classes during La belle époque to indicate that their nerves were finer and more delicate than those of other classes. But he fills his works with modern contents, especially when he blends fiction and fact, thereby expanding his oeuvre into a private mythology.

Dardel did not produce his best work until after the First World War and up to the Depression in the 1930s. This was a turbulent time throughout Europe. The war had laid the world in ruins and old values no longer applied. This gave rise to a sense of having gone astray, but paradoxically also to a new freedom. “The world only exists in your eyes – your conception of it. You can make it as big or as small as you want,” writes F. Scott Fitzgerald, commenting on the so-called jazz era of the 1920s. And in Sweden in 1922, Karl Gerhard borrowed a Danish tune and wrote a new couplet, “Jazzgossen” (The Jazz Chappy):

I read in dusty old novels,

which can be such a bore,

that brave young men

wore harness then,

in those days of yore.

Oh no, you speak of customs quaint,

of damsels on horseback fair,

But what a modern man wants now

Is a party everywhere.

Yes, here comes a gay young chappy,

With his trousers very sharply pressed,

In his suede shoes oh so happy,

Like a jazzy dancer neatly dressed.

His slim waist has belt and buckle,

He’s such a fop,

He will smile and wryly chuckle,

below his Eton crop.

Both Karl Gerhard’s couplet and Fitzgerald’s crass idealism remind me of Nils Dardel. So as not to be hurt by life’s hardships, Dardel turned life into theatre. Behind the occasionally scandalous playfulness lay a great por¬tion of earnestness. A young boy lived inside Nils Dardel throughout his life. But also a cynic, who knew he was going to die before old age – which made him a restless soul. Creativity, however, seemed to keep his spirits up, and his paintings of fictive or real demons and events had a veritably therapeutic effect.

Dardel experienced a revival in the postmodernist 1980s. His figurative, style-blending of highbrow and lowbrow, together with his mixture of seriousness and irony, could be interpreted in line with a number of postmodern theories. However, I also suspect that Dardel the dandy got to symbolise a rebellion against the ascetic and politically correct social climate that Sweden had experienced in the 1970s. Klas Östergren’s breakthrough novel Gentlemen was published in 1980, Lustans Lakejer flaunted their hedonistic lifestyle on the music scene between 1979 and 1986, and Nils Dardel’s The Dying Dandy (1918) was bought and sold several times over at record prices. This painting became something of an icon for the pleasure-seeking 1980s.

Time may have caught up with Dardel in that decade. His lifestyle was no longer considered controversial, and his artistic subjects could be experienced without being swamped by the autobiographical element. For it is in this very intersection between private and universal that Nils Dardel’s art operates. I am reminded of Bertolt Brecht, who once said that a photo of a Krupp factory merely shows what the factory looks like. To understand the conditions of the factory workers, you have to perform a play. Nils Dardel performed a play staking his own life. It is perhaps no coincidence that he began his career in the era of Dadaist pranks: “Dadaism is the laughing equanimity that plays Russian roulette with its own life as the stake, since it no longer wants to be complicit in the European swindle. Dada has a tendency towards the non-tragic, a balance within the regularly self-perfecting freedom about which it does not give a damn,” writes Raoul Hausmann in the manifest Dada ist mehr als Dada (1921).7 The “European swindle” should be read as the First World War, a mechanical mass-slaughter that outraged the dadaists. With more or less nonsensical antics, they created a form of anti-art, seeking to declare that war dissolves all values and that previous moral, ethical and aesthetic programmes had proved to be completely meaningless.

Could Nils Dardel’s dandy, who averts his eyes from the global catastrophe and instead devotes himself to more or less complicated love affairs, be compared to the dadaist who “plays Russian roulette with his own life as the stake”? The often wild combination of laughter and crying, sensibility and madness that characterises Dardel’s art has a kinship with the dadaist and surrealist art circles in which Dardel moved, especially in Paris. Stylistically, however, he went his own way. But the dream visions in his works undeniably flow towards a proto-surrealist ocean.

Perhaps we also feel familiar with Dardel’s imagery in view of today’s media society, where reality and fiction are intermingled, entertainment merges with information, politics becomes a spectacle, spectacle becomes politics. We are taught to be active citizens by keeping up to date with world events. But can we structure or differentiate between truths and lies, right and wrong, reality and fiction? What is dream and what is real? These are questions that Nils Dardel anticipated more than a century earlier.

Perhaps he even made art out of “dandyism”? It is as though I can hear echoes of Beau Brummell’s dandy in Cecilia Berggren’s article on the peculiar community of androgyny: “We could discuss and establish a dual coding in Dardel, where the duality lies in how his subjects can be appreciated from two different angles by two different audiences: one that appreciates the colours, the visual formula and the quirky elements such as dancing monkeys, and one that sees the visual formula and its components as an allegory on a strategy and a way of exhibiting sym-bols to the public, knowing that only a few will understand them entirely.”

I am not convinced that Dardel’s works contain a secret language. The dual coding is of a more associative nature. It is a role play that broadly concerns how identities are created and recreated. Role play has been the fundamental basis of social psychology since the 1920s. In his seminal work The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life from 1959, Erving Goffman developed this concept by transferring metaphors from theatre, such as acting, costume, prop, script, setting and stage to social behaviours. It was no longer a privileged few who could play around with their image. As social media offer new opportunities for self-representation, role play has become available to more and more people.

One of the clearest exponents of this development is probably David Bowie. His various enactments of himself form a rich patchwork of historical references that I, like the exhibition David Bowie is at the V&A in London (2013), dare say is a multi-performative work of art in its own right. In the exhibition catalogue, Camille Paglia provides a historical perspective on Bowie’s gender-transcending role play: “Bowie’s theatre of gender resembles the magic-lantern shows or phantasmagoria that preceded the development of motion-picture projection.” And she continues: “The multiplicity of his gender images was partly inspired by the rapid changes in modern art, which had begun with neoclassicism sweeping away rococo in the late eighteenth century and which reached a fever pitch before, during and after World War I.”

Paglia is referring to the milestones of dandyism, and Bowie himself claims to be deeply influenced by all art forms, but perhaps most of all by expressionism and dadaism. If we study Bowie and his array of personas, he was undeniably inspired by the radical and liberated art scene that prevailed around World War i. The same era shaped Nils Dardel’s boundary-crossing artistic oeuvre. Can’t you just see him standing in for the Thin White Duke!?