Anders Widoff, Abstract (No 4), 1991. Chair, textile and acrylic glass, 130 × 80,2 × 45,5 cm.

Bildupphovsrätt 2021

Time Is a Place. Works from the Moderna Museet Collection

Text: Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff

It is a simple grey-white kitchen chair with a chequered brown seat cushion – bringing to mind Swedish folkhem aesthetics. In front of the chair, screwed onto it, is a sheet of plexiglass. The effect is sensational. Such a simple measure – applying a glass pane to an everyday found object and thus negating its function and turning it into a historical artefact. Widoff transformed a profane object into a myth. It is just too good. The transparent surface makes the chair into an image, and it was through images that I wanted to understand the world. I do, after all, derive all my information and inspiration from the work of other photographers and artists. Reality doesn’t interest me much beyond its representations and visual manifestations, assertions and sights throughout time and space and everything I see becomes mine; I own these images and use them.

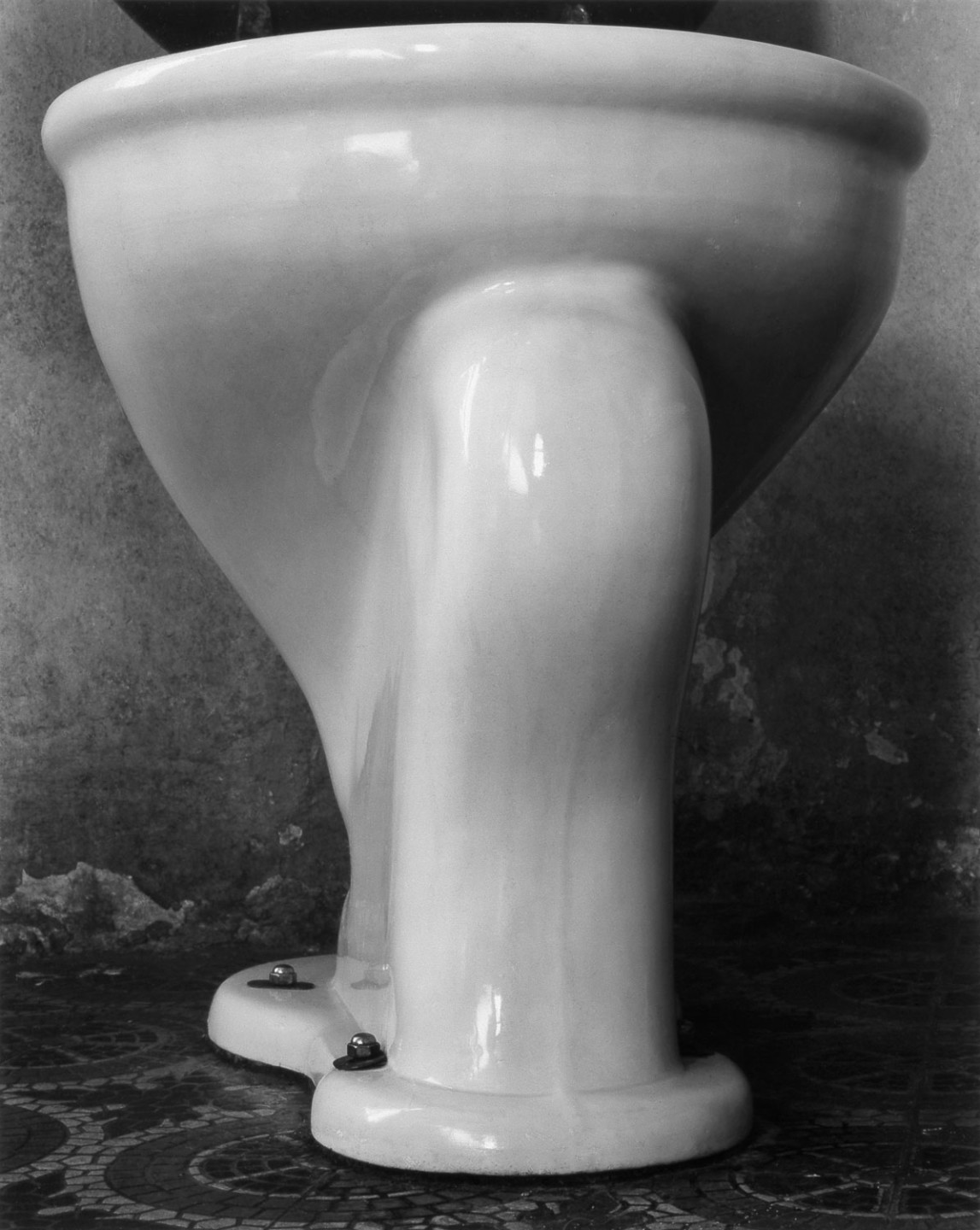

Why did Edward Weston once choose to photograph a toilet from an unconventional perspective – from below, up close, without demonstrating the object’s actual function? A short text on the Metropolitan Museum’s website claims that Weston’s ”Excusado” (1925) relates to the sensual curves of the female body. I don’t see anything other than a bulge, a male sex organ in a pair of tight pants. The best and the worst thing about images is that they can be interpreted: they’re surfaces for projection, useful tools for the imagination. At once phenomenal and dishonourable, beguiling and obsequious.

Some of the images I’ve chosen irritate me: those feet hanging down from a hatch in the ceiling in Andy Warhol’s black-and-white photograph from 1985, for example. And the façade in Lewis Baltz’s image from 1973 is so closed up that it makes me short of breath, yet I keep coming back to it and feel compelled to include it in my presentation of work from the Moderna Museet collection. Cindy Sherman’s repugnant figure in ”Untitled #123” (1983) – what does she want from me? The figure presents herself in contradictory lighting with an ingratiating smile and I choose to be provoked. In the same way that an artistic process is often the result of many choices, a viewer also must choose to invest their gaze in an image. It is a misapprehension that there is something specific to be understood in art, which is a pity since that approach stands in the way of real encounters. There is nothing to understand – rather, images offer a dialogue that goes against demands for cause and effect. No image wants to be invisible – it wants to be questioned and acknowledged.

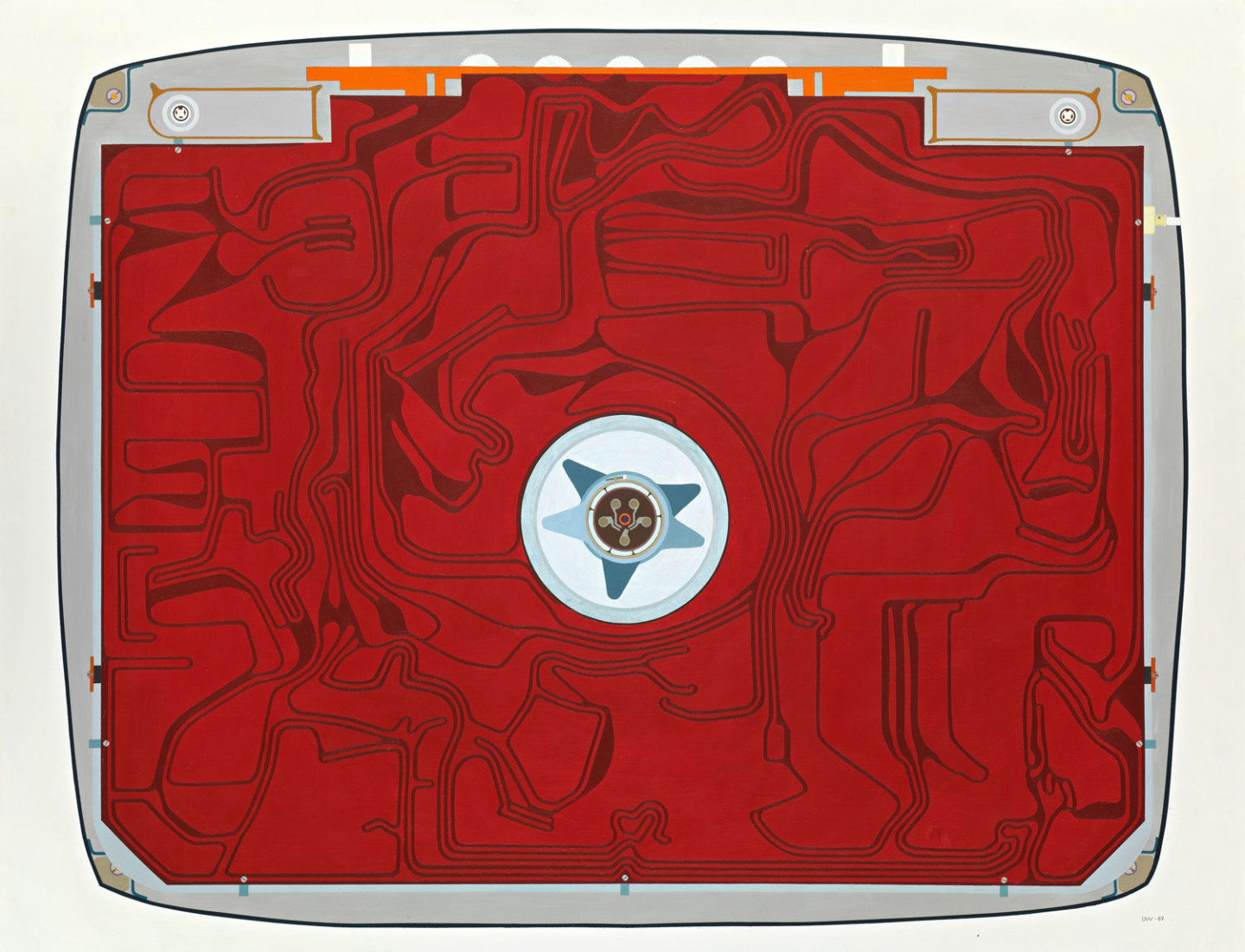

Ulla Wiggen’s sensual red painting from 1967, the year of my birth, seems quite odd in this context, but when Inge Holm’s infrared photographs, taken thirty years earlier, appear in the documentation of the collection I peruse, a visual connection emerges. The network resembling a circuit board that Wiggen painted in ”Den röda TV-n” (The Red TV) relates to the veins and blood vessels that Holm wanted to reveal in the bodies from the 1930s, which look like lightning. Both artworks are uncomfortably beautiful. Connecting them reminds me of the invisible network in the universe that links bodies, technologies, thoughts, and images.

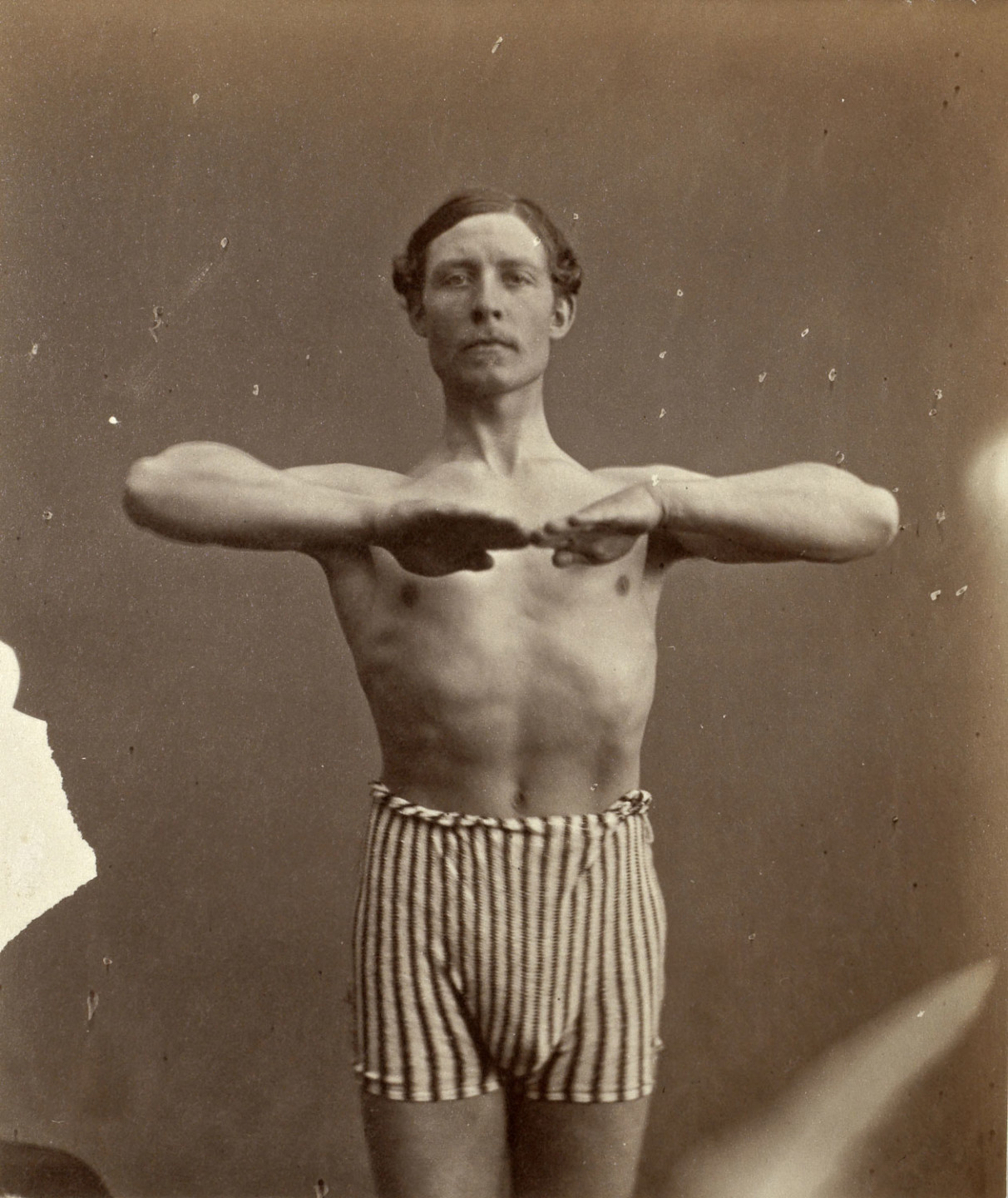

My selection surprises me a bit. There’s a lot of movement, people, body parts. But that’s because I’m after the ideas I find behind every image. Like Artur Boström’s comparative photographs of hands or reeds, which are studies of technical qualities rather than unique extremities or specific flora. And Carl Jacob Malmberg’s artless photographic series ”Gymnastik” (Gymnastics), in which dressed and naked men demonstrate the body’s motor skills. The images end up somewhere between the simple aesthetics of instruction images and homoerotic reflections on male elasticity. The nude man is still wearing his socks. It looks like pornography from the 1970s, when no man ever took off his tube socks before having sex.

Every image I’ve selected has asked me a question or argued its case. I have answered by affirming its existence. Together the pictures constitute an incomplete map of my own work; many works important to me are not included in the Moderna Museet collection and others have not yet been made.

I have self-indulgently incorporated one of my own photographs. ”The First Self-Portrait” (ca. 1987) is precisely what it claims to be. Taken over thirty years ago, long before I chose to work artistically, the photograph results from an assignment at a preparatory college: my first staging, and I chose to present myself as Hamlet. At the time I often dwelt upon “to be or not to be”, which is quite natural for a nineteen-year-old, I guess. I count five skulls in my exhibition-within-an-exhibition and feel quite satisfied.

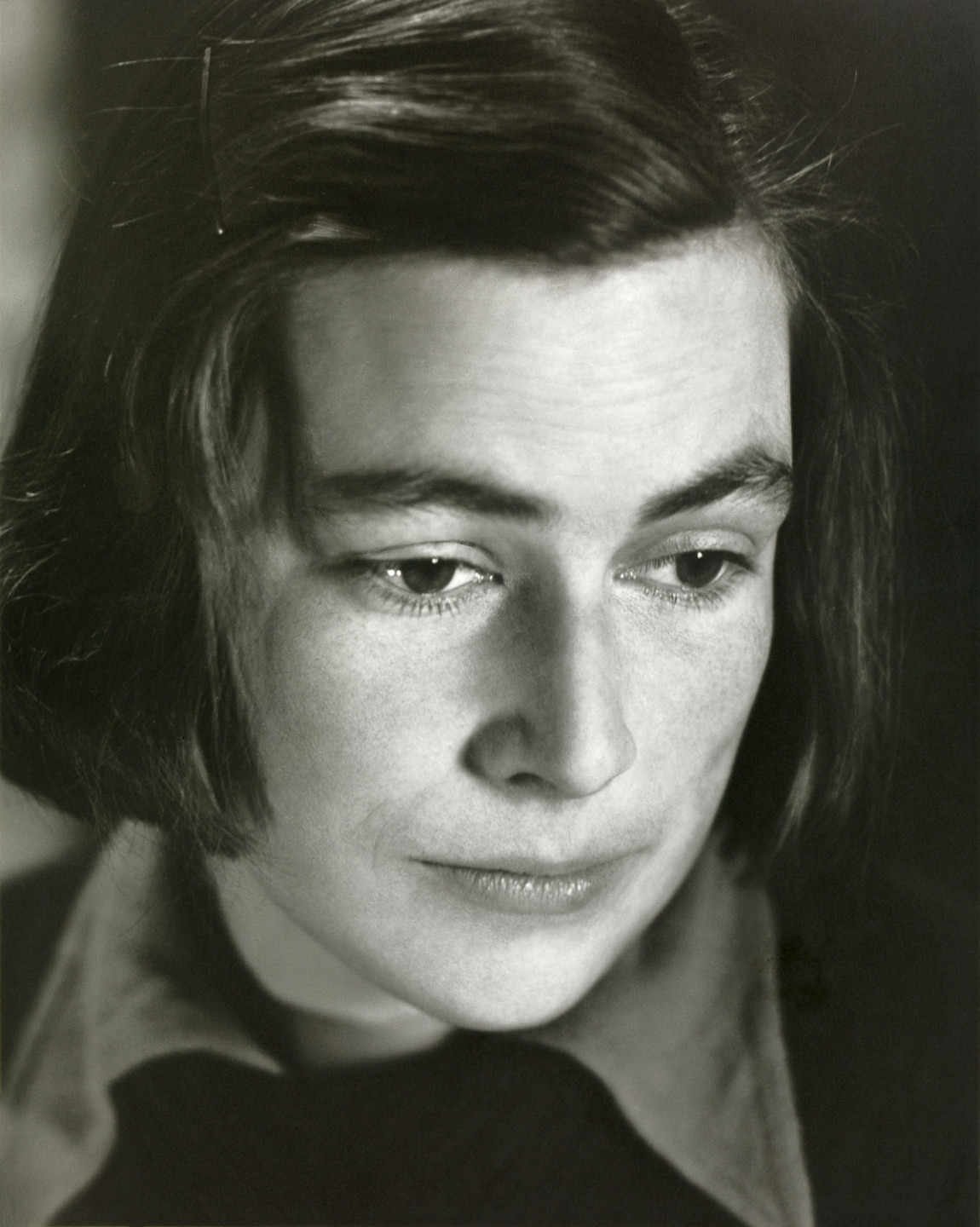

There’s a portrait by Kerstin Bernhard depicting the artist and translator Ann-Mari Brising that I love. I want it to be me. I want to look like her, to have the same pretty gaze that radiates self-confidence, assurance, and courage. It’s a photogenic face. I project my feelings onto this visage, which was photographed in 1934. Lindberger died in 1997.

That’s how photographs work; they defy time and space and are always at the service of manifold fantasies and speculation. I also see myself in Teddy Aarni’s strange group portrait of four women with ponytails and a little child – they’re all me, even the child. But a completely different feeling emerges when I encounter Lena T, photographed by Stina Brockman in 1980. Lena looks me in the eye and bowls me over with her charisma. Lena is definitely not me. She sits there, naked, on the sofa and regards us all with her critical, slightly disillusioned gaze.

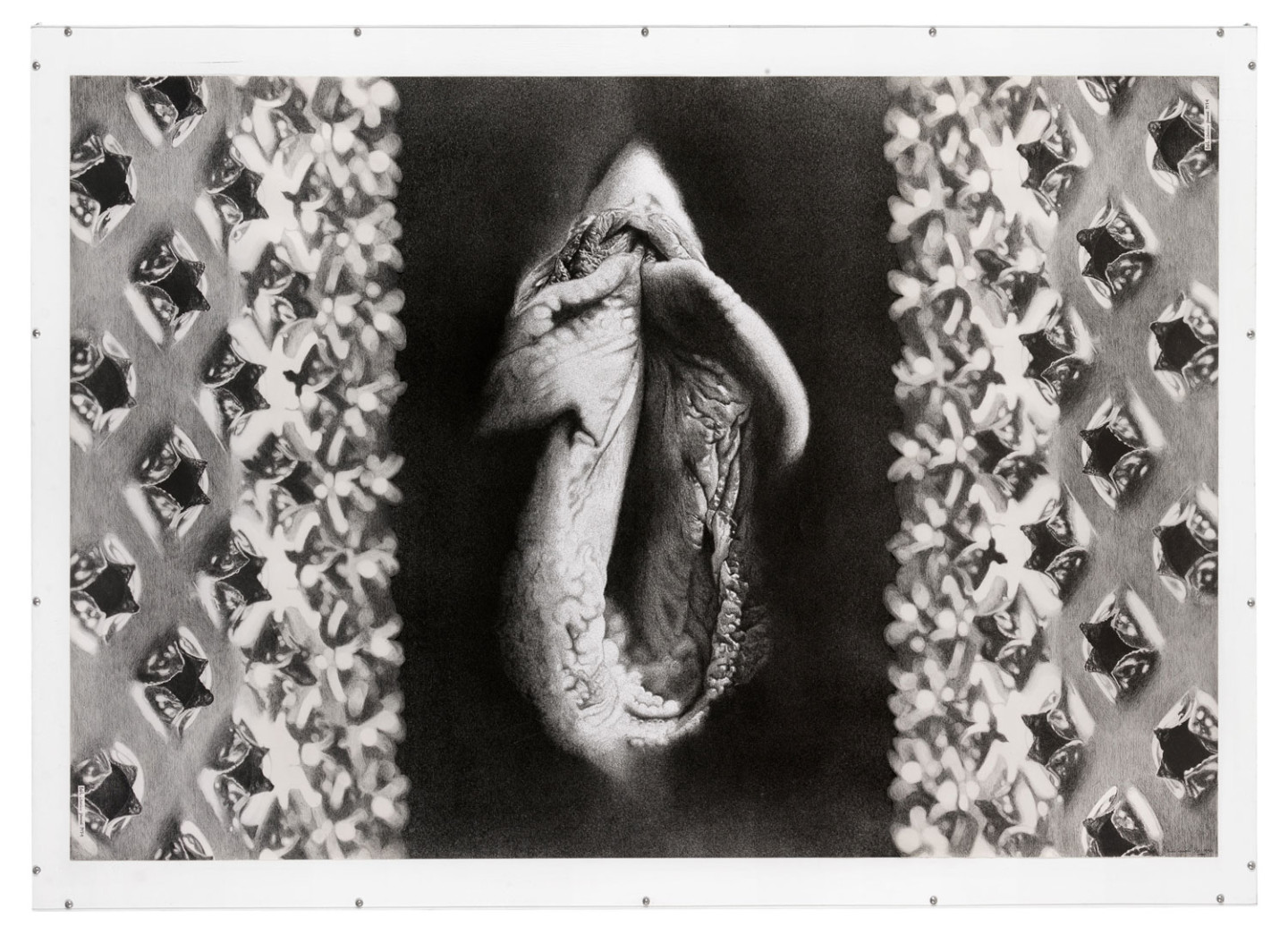

”Trycket ska minska” (Reduce the Pressure, 1975) is an image by Beth Laurin in which a sensitively drawn clitoris is flanked by two grater-like patterns. The artwork is brutal and beautiful and it hurts to look at it. I can identify with the physical pain that it evokes, but it’s also painful to realize that so-called women’s art has often needed to express the experiences of being a woman in order to receive attention or acknowledgement. My own work is included in this. Lately, when I teach students born in the 1980s or ’90s, I see a change. The majority of the students are women, queer, or norm-breaking in other ways and in their work many of them deal with issues other than gender and identity.

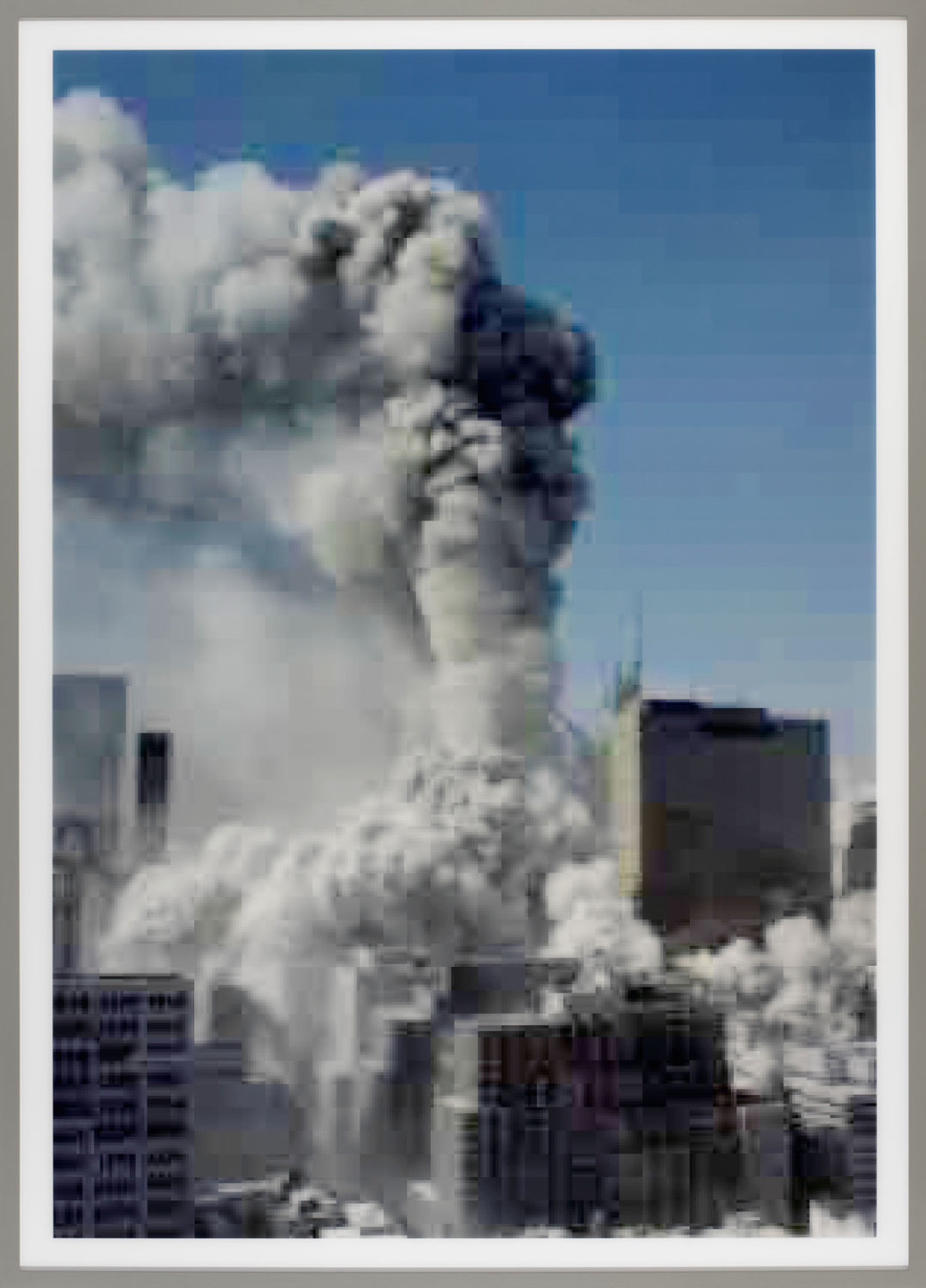

Something strange happens in front of Thomas Ruff’s 2006 photograph ”jpeg td02”: I tear up when I look at it. It’s a strange image taken from a series of JPEG files downloaded from the internet. A high-rise building, perhaps the World Trade Center in New York, implodes after an explosion. Regardless, the image represents the violent explosions that occur all over the world. When I think about why I am so touched by it, I realize that it’s not about the tragedy that the work represents but about the love of art.

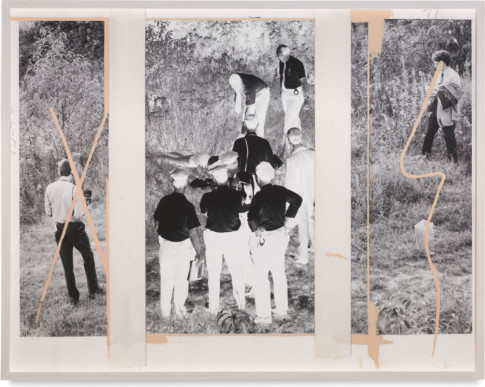

The actual act of using a simple JPEG file to blow up a photograph to several square meters is marked by an idle trust in one’s vision, which only an artist can have. But my tears are also about the conceptual gesture of using a media image as a starting point of critique; it throws me back to the beginning of the 1990s, when I (we) were first hit by the postmodern storm that blew in primarily from North America and Canada. Artists and photographers such as Mike Kelley, Barbara Kruger, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, and Jeff Wall, to name just a few, showed us young artists new strategies for taking photographic tradition further. With her triptych ”this girl has inner beauty” (1990) Lotta Antonsson – a friend and role model of mine – reflects the times with feeling, humour, and a new photographic rhetoric.

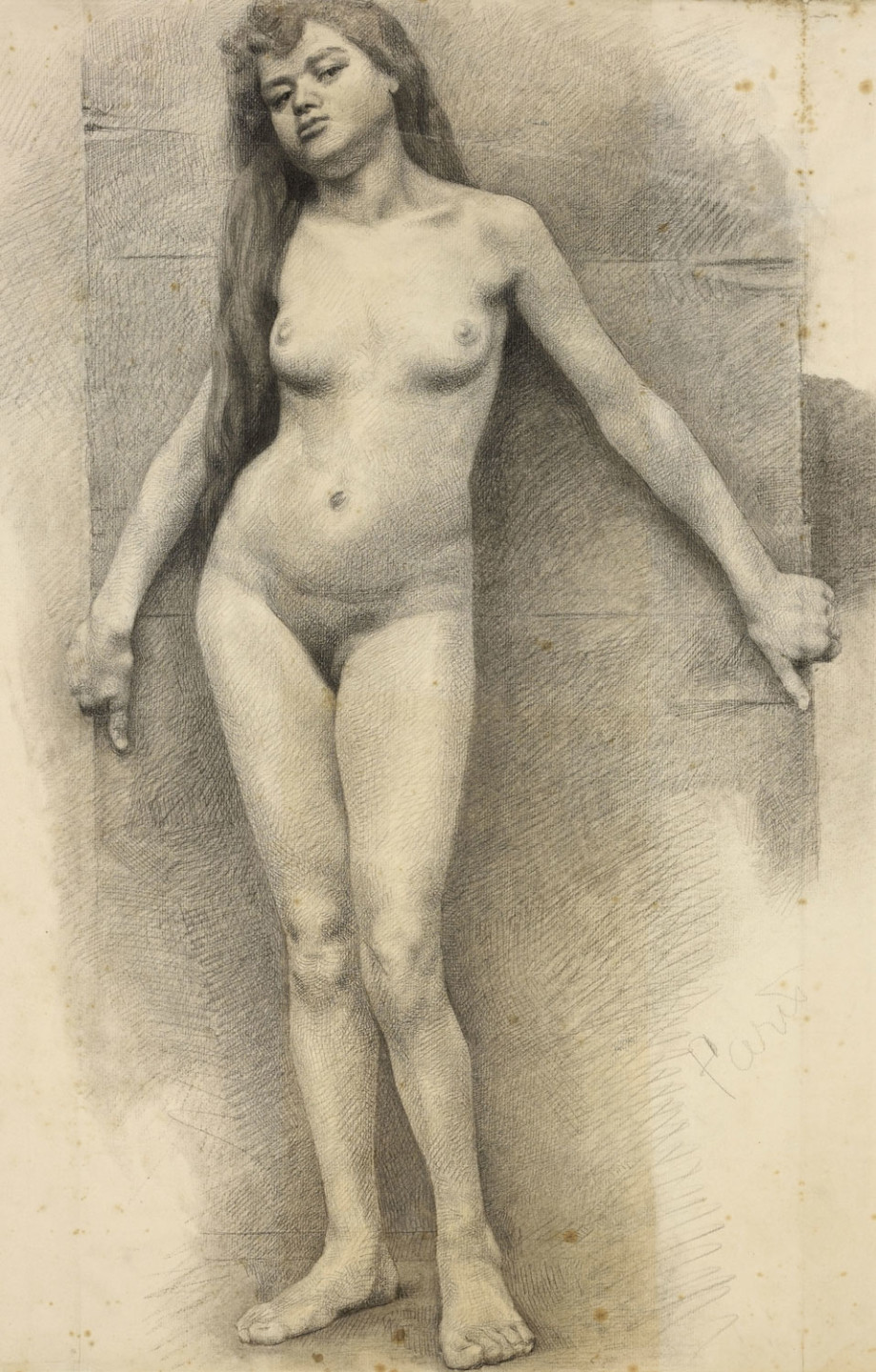

One of the images I struggle to put into words is the drawing by Ivan Aguéli. Who is she, this young woman whose unbeatable attitude backs the viewer up against a wall? She is drawn with a sure hand and inscribed into history with love. Our world is the sum of all actions, events, and thoughts. A fraction of it all has been transformed into images, and sometimes I reflect on everything I’ve missed, everything that has disappeared for one reason or another, or simply never became an image. The thought is overwhelming.

Von Hausswolff’s selection from the Moderna Museet

collection

Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff has been invited to make a selection of work from the Moderna Museet collection for ”Alternative Secrecy”. The selection can be seen as an exhibition in an exhibition, as a reference point and background for her way of being inspired by and using other artworks and images in her own practice. With her well-trained eye she has chosen around fifty works.

Some of the artists and photographers included: Rosa Becker, Larry Clark, Lisa Jonasson, Maria Lindberg, Irving Penn, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Oscar Gustaf Rejlander, Melissa Shook, Joel Sternfeld, Otmar Thormann, Gunnar Thorén, Brian Weil, Martha Wilson, Rolf Winquist, and Francesca Woodman.

She has also taken a look at the museum’s rich collection of film and chosen around twenty films and video pieces, most of them from the 1990s.