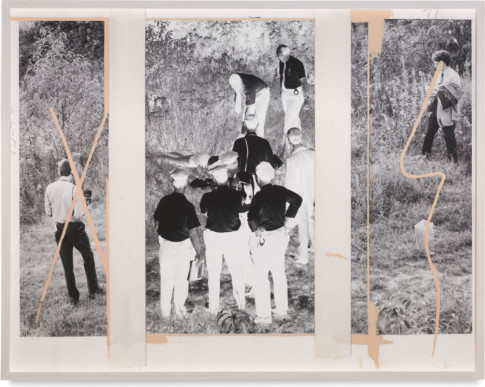

Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff, Everything Is Connected He, He, He, 1999 © Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff

On Photography in a World of Images

Text: Anna Tellgren

A few years ago, the artist was rumoured to have said that she had produced her last exhibition. She was done. But this, thankfully, didn’t prove to be entirely true and now she is back in full force. ”Alternative Secrecy” encompasses some one hundred artworks from von Hausswolff’s entire career. She has even created a few new works for the exhibition, and for the museum’s foyer she has designed a wallpaper, which functions like a prelude to what awaits in the large hall. Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff has also been invited to make a personal selection of works from the Moderna Museet collection. These works will be presented as an independent part of the exhibition while still maintaining a dialogue with the artist’s own work.

In the early 1990s, a new generation of young photographers emerged who worked with and developed what is called photo-based art. The period is well documented and has been described in a range of articles and books about Swedish art history.[2] It is commonly noted that many of the successful artists at the time were women and that a change in expression and subject matter could be discerned in the new generation. Lotta Antonsson, Annica Karlsson Rixon, Maria Miesenberger, and Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff are some of the artists mentioned in this context.[3] The emergence of photo-based art was based in postmodern discourse, which had its definitive breakthrough in Sweden in connection with the 1987 exhibition ”Implosion. A Postmodern Perspective” at Moderna Museet.[4] It included work by the likes of Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, Laurie Simmons, and Cindy Sherman – artists who adapted and used the photographic image in their work in different ways and were included in the Picture Generation grouping. Postmodern art became the object of heated theoretical and philosophical debate, inspired by French poststructuralism. [5] Several influential theoreticians have defined post-war photo-based art as constantly referring to something, to reality or to other images.[6] This theorizing also led to a new form of critical studies of, and based on, the history of photography, in which a pervading topic was stressing the discursiveness of photography, that is to say, what lay beyond the image and governed its interpretation. [7] Subsequently these thoughts and theories became natural parts of the way art and photography were taught in Sweden and thus a new generation of artists emerged.

Two institutions that played a pivotal role in this were the programmes in photography at Konstfack (University of Arts, Crafts, and Design) in Stockholm and the School of Photography in Gothenburg. Under the direction of Hans Hedberg, head of the Academy of Photography at Konstfack between 1992 and 1999, the educational programme was revised to make it more theoretical, including elements of philosophy and art theory.[8] Tuija Lindström was professor at the School of Photography and Film at the University of Gothenburg between 1992 and 2002.[9] During her ten-year tenure the teaching moved in a more theoretical and artistic direction, which had an immense impact on the students who graduated in that period of time. Tuija Lindström and Hans Hedberg had both studied at Konstfack.

Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff moved to Stockholm in 1991 to start attending Konstfack. Born in 1967 as Annika Söderholm, she grew up in Gothenburg with her parents in the district of Stampen. As a teenager she came into contact with the photographer Tom Benson, who was a pioneer when it came to working with staged photography and montage. She subsequently majored in photography at Sven Wingquist High School. She also has a background in music and the cultural circles around the record label Radium 226.05 in Gothenburg.[10] During an internship at Radium she started photographing the musicians connected to the label. One of them was the singer and actor Freddie Wadling and for a few years von Hausswolff was a member of and singer in the punk band Cortex.[11] This was when she met her first husband, the multitasking composer Carl Michael von Hausswolff, known amongst other things for his art project revolving around the fictitious kingdoms of Elgaland-Vargaland, which he developed together with the artist Leif Elggren. The encounters with artists and musicians and the DIY attitude that von Hausswolff took with her from the punk scene were crucial in her decision to enrol in art school. She was accepted into Konstfack and studied there for three years until 1994. Fellow students at the Academy of Photography included Lotta Antonsson, Henrik Håkansson, Maria Miesenberger, and Christine Ödlund, to name a few. The students at the Academy of Photography had a clear need to push further. Their photographs left the walls and several of them experimented with making sculptures and installations. At Konstfack, students in photography, painting, textiles, and sculpture also worked in other media and moved beyond their educational programmes’ predetermined frameworks, something which in itself reflected the interdisciplinarity of contemporary art.[12] Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff continued her art education and attended the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm between 1995 and 1996, where she majored in graphic art and video. Looking back and summarizing this period, it becomes clear just how crucial and strategic these choices were not just for her personally but for the entire general discussion and direction of art photography.

From the 1970s onwards, Swedish photography underwent dramatic changes.[13] From having been dominated by a strong documentary tradition and ideology, a more artistic strategy could be discerned. In the early 1980s a group of photographers formed around the legendary photographer Christer Strömholm, gravitating towards a more poetic, private, and dramatic aesthetic – towards art.[14] Several of them worked with large-format cameras, experimented with different photographic processes, and published their projects in carefully designed photobooks, for example Dawid, Walter Hirsch, Gerry Johansson, and Gunnar Smoliansky. Fotograficentrum (Centre of Photography) at Sankt Paulsgatan 3 in Stockholm became a gathering place for photographers and photo enthusiasts, and some of the aforementioned photographers had exhibitions there.[15] The gallery continued throughout the 1990s to present the work of many of the young and up-and-coming names in art photography, both in Sweden and abroad. In 1992 the gallery changed its name to Galleri Index and a few years later, in 1998, liberated itself completely from its origins and instead became Index – The Swedish Contemporary Art Foundation. Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff participated in the exhibition ”Home. A Study in Politics” (1993) at Index, with ”Utan titel (En studie i politik)” (Untitled (A Study in Politics)) from the same year.[16] The work consists of a series of oval close-ups depicting the bruises of battered women; the artist accesed these photographs through the National Board of Forensic Medicine in Solna. When, after a while, she lost control over the context in which the images were shown, she chose to withdraw the work, and it no longer exists today. For ”Alternative Secrecy”, von Hausswolff has reused the negatives and made a new version of the work.

As a result of the new direction and organization at the gallery of Fotograficentrum, the periodical ”Fotograficentrums Bildtidning” became an increasingly important forum for photo-based art, which led to the magazine also changing its name in 1992 to ”Index – Contemporary Scandinavian Images”.[17] In it the most contemporary within photographic art was presented alongside theoretical texts about art and photography.

One of the first and more comprehensive photo exhibitions in Sweden that tried to embrace the new ideals and mix different directions in photography – such as fashion, documentary, press, and art photography – was ”Lika med. Samtida svensk fotografi” (Equal To. Contemporary Swedish Photography), which was presented in 1991 at Moderna Museet.[18] When Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff moved to Stockholm, the Department of Photography at Moderna Museet still existed, with its exhibition spaces in the western wing of the old museum building in Exercishuset on Skeppsholmen.[19] In those years it hosted exhibitions of an older generation of photographers such as Danny Lyon (1992), Hans Hammarskiöld (1993), and Irving Penn (1995), as well as Nan Goldin (1993), Karen Knorr (1993), Alfredo Jaar (1994), Allan Sekula (1995), and Pia Arke (1996). ”Equal To” was the beginning of a shift towards collecting and showing a different type of photographic image than the classic black-and-white and documentary photography. Other exhibitions that presented the new photo-based art were ”Index. Contemporary Swedish Photography” (1992), ”Prospects. Contemporary Swedish Photography” (1994), ”De utsatta. Nutida fotografi från Skandinavien” (1994), and ”Stranger than Paradise. Contemporary Scandinavian Photography” (1994).[20] Among the participants in these undertakings were Lotta Antonsson, Magnus Bärtås, Annica Karlsson Rixon, Patrik Karlström, Martin Sjöberg, Sven Westlund, and Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff. She was included in ”De utsatta”, a reworked version of ”The Abject” produced for the International Photographic Triennale in Oulu in 1994, but also participated early on in exhibitions of contemporary art, such as ”Revir / Territory” (1994) at Kulturhuset. In the 1990s, von Hausswolff had several gallery shows in Sweden and abroad and she became a prominent and evident part of the Swedish and Nordic art scenes. She represented Sweden in the 23rd Biennale in São Paulo in 1996, as well as the Nordic Pavilion in the 48th Art Biennale in Venice in 1999.

Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff’s breakthrough came with the series ”Tillbaka till naturen” (Back to Nature, 1993), which she had already exhibited in a student exhibition at Konstfack in the autumn of 1993.[21] The students had been given the assignment to work with the theme of nature for one semester. In the series, von Hausswolff staged victims, in the form of raped and murdered women. Bodies lie naked on the roadside, in bushes, or a forest glade – in nature. The images are very disturbing and reminiscent of crime scene documentation by the police, newspaper images, and crime films. Her method of recreating crimes and presenting them in large format was very timely, yet the brutal contents shocked many who saw the subject matter for the first time. In the early 1990s, Swedish society had not yet been flooded with the explosion of crime fiction and crime novels we experienced in recent years. However, photo and film history are full of images of crime, violence, and war.[22] Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff’s method can be likened to how a filmmaker works: she stages and leads the viewer into and out of her world. At the time, the title of the series and the tableau-like staging gave rise to comparisons with Nordic landscape painting from the turn of the previous century.[23] A few years later, von Hausswolff made ”Hey Buster! What Do You Know About Desire?” (1995), one of her most acclaimed works, which was acquired early on for the Moderna Museet collection. Once again, we see a lifeless prostrate woman, this time on a beach, with a German shepherd waiting by her side – the depiction of a crime that will never be investigated or solved. The image is pale and matt, which is amplified by the fact that the large chromogenic print, type C, is covered with a dense laminate. The dog recurs in several of her works and represents some sort of security, a witness, who sees but cannot tell. Using English titles has become characteristic of von Hausswolff’s work. She uses the ambiguity in the English words and expressions and transfers them to her artworks and exhibitions. The titles give us an idea of how the artist wants us to perceive and interpret her images.

Among her early works we also find the theatrical ”Still Life (John and Jane Doe in the Arena)” (1995), in which a man and a woman are lying lifeless on a deserted tennis court. The title refers to the names given to unidentified corpses by the American police – another unsolved crime, which is set on a tennis court, like a large stage. Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff has mentioned how she found and read the periodical ”Nordisk Kriminalkrönika” (Nordic Crime Annual) and was fascinated by the detailed images of the different crime scenes.[24] Her own motifs are a kind of commentary on this aesthetic tradition, with their long-established conventions. We don’t get any answers in her crime images, but we become conscious of how frequently these kinds of brutal images, especially of women, have been made and continue to be made in our culture. According to von Hausswolff, her early series are a result of the intense feminist discussions that raged in her years at Konstfack.[25] However, the most distinctive thread running through her body of work is the influence of classic photography that is the basis, a recurring point of reference, and an inspiration in the creation of her images. The staged scenes reveal a relationship with pictorial history, while at the same time she creates her own worlds. Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff started out as a printer and photo assistant, working for ”Göteborgs-Posten” for a year, but she was not comfortable in the role. Against the backdrop of the debate and criticism that documentary photography was subjected to from the end of the 1970s onwards, she positioned herself among the many artists who questioned and tried to revitalize the documentary tradition both through texts and artistic projects.[26] The ambiguity of the photographic image is what interests her. Photographs always have a relationship to reality, an indexical relationship, and represent a kind of proof for what once existed before the camera.[27] This relationship is used by von Hausswolff to create an ambivalence with regard to her images. She wants to get us to recognize, become unsure, and then start reflecting on what we are actually seeing.

In connection with an invitation from Kalmar konstmuseum in 1994 to participate in an exhibition with the title ”Processer. Crimes in Mind”, Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff created images of bubbles, made with bubble gum. She herself blew the bubbles and is visible behind them in the images. Quite a simple idea, which she developed into a series of seven pictures entitled ”Utan titel (med bubbla)” (Untitled (with Bubble), 1995) and then, the slightly bigger ”Alone with Bubble” (1996), a new and larger version of which is included in the current exhibition. On one level the work is a self-portrait, on another it is not, since the person (Annika) is hidden behind the bubble gum sphere. It could be a completely different woman. In other works, the models often bear a striking resemblance to the artist herself. A common trait across von Hausswolff’s works is that they have to have a connection to herself in some form: what she is interested in, what she does, her memories and life. At the same time, they are always characterized by a great deal of integrity. Later, she created another work on that theme, ”Försök att hålla ordning på tid och rum” (Attempting to Deal with Time and Space, 1997), which also became a series of seven pictures that can be interpreted as a documentation of and reflection on the creative process itself.[28] She breathes life into and gives shape to this rubbery material, tries to keep time and space in check, and the whole project becomes some sort of performance in which she creates before the camera. The bubbles are also present in the work ”Utan titel” (Untitled, 2006), in which a malleable and elastic bubble is worked by a pair of hands in a series of eight photographs.

In Venice in 1999, von Hausswolff exhibited a suite of suggestive, mysterious images in which she dealt with different psychoanalytical topics that interested her. In ”Allting hänger ihop ha, ha, ha” (Everything Is Connected He, He, He, 1999) a pair of stockings lies soaking in an old-fashioned sink. The image is based on an actual memory from von Hausswolff’s childhood, when she would often come into the bathroom and see her mother’s underwear in the sink, waiting to be washed.[29] In different ways she investigates the relationships, the trinity of mother– father– child, and the situations she stages often become absurd and humorous. Certain characteristics in von Hausswolff’s images bring to mind surrealist photography. She has mentioned before that she is fascinated by Hans Bellmer and his way of objectifying dolls in his photographs from the 1930s.[30] In the series ”SPÖKE” (2000), she developed the surrealist aesthetic further. The pictures were presented in an installation, in a space along with pot plants, two plastic chairs, and a few red fire extinguishers – an installation that will be reconstructed in this exhibition. The series of photographs was taken in von Hausswolff’s parents’ house as they were moving out, and in it she continues her investigation of image and space. A few clothes hangers in a wardrobe and a forgotten bra. It’s lit from below and lights up the empty rooms with the same cold, hard light that she has often chosen for her compositions. No people are featured in the pictures, just traces of them. The same goes for the work ”Untitled (Shirt)” (2002) consisting of twenty photographs of shirts in different nuances of pink and beige. Yet the garments still seem to be alive, or corporeal, with their carefully arranged knots and perfect collars. The absence and presence of bodies, or the female body, has been a recurring theme in several of her series. For this exhibition von Hausswolff has chosen five of the shirts and recreated them in a bigger format.

Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff’s large, well-composed colour photographs behind plexiglass seem almost like objects. It was a natural move for her to go from two-dimensional to three-dimensional work. The first was a curtain – a gigantic piece of shiny beige-pink cloth – which was given the title ”Minnet av min mors underkläder förvandlat till ett flamsäkert draperi” (The Memory of My Mother’s Underwear Transformed into a Flameproof Drape, 2003). The Moderna Museet collection includes the work ”Esoteric Forensic” (2007), one of five cupboards, which not only brings to mind forensics, but also evokes associations with something hidden and with mystical teachings. We don’t know what the cupboard contains, since the glass front is covered from the inside by a curtain and locked. All of it is in the same beige-pink colour that von Hausswolff is so preoccupied, if not obsessed, with. Some of the objects and materials that she has used in her objects have also featured in her earlier photographs, the two-dimensional works, such as an illuminated curtain, drapes, a chair, and the red blinds. There is also a photograph of a red plush sofa with its cushions lying in a jumbled mess on top of the seat, which she simply called ”Domestic Sculpture” (2002). The exhibition includes the artwork ”Social Abstraction” (2010 / 2019), which consists of two cupboards made of white chipboard, in which the original white blinds have been replaced by red ones, which cover the inside of the cupboards’ openings.

The work ”I Am the Runway of Your Thoughts” from 2008 contains twenty-five photographs, both colour and black-and-white, divided into nine parts, that were presented in a protracted suite reminiscent of an airport runway.[31] Here von Hausswolff returned to working in long series, such as the bubble works that she produced a decade earlier. The work, which is a play on colour and form, light and shadow, and is about the artist’s own fear of flying, captures an attempt at controlling an unidentified threat. Here we see close-ups of a woman with a model aeroplane at different angles and the motif also has blatantly sexual connotations, with the phallic symbol close to the woman’s half-open mouth. It’s a suggestive work that also makes reference to the psychoanalytical theories that von Hausswolff is so interested in and influenced by.

Also in 2008, the American company Polaroid announced that they would stop producing their instant film. This meant that von Hausswolff was forced to find new working methods. Throughout her career up until then, the Polaroid camera had been a tool for her, like many other professional photographers, to try out ideas, colour, form, and lighting.[32] In light of the change in availability of the film, von Hausswolff developed her working process in two different directions. After spending her post-Konstfack years basically only working with staged photography, she now embarked on a photographic collaboration with the historian Jan Jörnmark. Their work resulted in the book ”Avgrunden” (The Abyss, 2011) in which they investigated the traces of capitalism in geography and described the background to and emergence of the IT and property sectors’ collapse throughout the USA, Eastern Europe, and East Asia. Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff went to deindustrialised Detroit and former Yugoslavia. In 2011 she created a number of works based on the collected material, using a grid with fifteen carefully selected images mounted behind plexiglass to compile and analyse some of the environments she had visited. ”In Untitled (For Sale by Owner)” (2011) we see a row of houses on a street in Detroit that reflects the city’s economic reality after the automotive industry closed down and the majority of jobs disappeared. In a similar way, von Hausswolff also assembled images of deserted schools, courts, and nightclubs. This provided the opportunity to reconnect with the documentary tradition and classic photography, which she loves and has been so reliant on. Around the same time she also created ”An Oral Story of Economic Structures” (2012 – 13), which consists of five, at first glance, seductively beautiful still-lifes with golden objects against black, turquoise, bright red, grey-white, and black-and-white backgrounds. On closer inspection, the pulled gold teeth take on a completely different meaning. It turns out that teeth with gold fillings are bought and sold online, where they exist as a commodity among many others, although it’s unclear where they come from. In this project von Hausswolff describes her buying the teeth at an online auction as an artistic initiative, as well as a conceptual project.[33] As with the images in ”The Abyss”, these still lifes demonstrate how political and economic events affect people’s everyday lives, often in brutal ways. Both works remind us of our dark history and urge us not to forget what happened.

The other branch of Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff’s practice after 2008 is about the death of analogue photographic technology and starting to work outside the darkroom. In some works, she documented the tools used in the photographic development process, such as various colour filters, lenses, and negative holders. Among them is ”The Phantacy of Focus” (2013), an image of a tool used to calibrate the lens of a camera. She also exhibited the fittings of old enlargers, known as easel masks, in a glass vitrine entitled ”Crop Memory Machine”, in an exhibition at the gallery Andréhn-Schiptjenko in 2015. The works can be interpreted as a kind of process of mourning for obsolete technology, as well as the whole mystique of chemistry and light that fixed the images on the photo paper in the first place, which is what has fascinated image makers and philosophers since the birth of photography at the end of the nineteenth century and what people have dreamt of since the camera obscura of the sixteenth century. Since the analogue technology is no longer available in the same way as before, von Hausswolff instead started using and reworking images that she collected over a long period of time and that have actually always been the starting points for her own creative process and thoughts. Her archive includes portraits, newspaper images, advertisements, films, as well as her own photographs that she has reused. The images were scanned and transferred onto enamel, and she also produced inkjet prints and painted over them with acrylics. The enamels were created using a technology used to print images onto mugs and other crockery. With this, von Hausswolff has entered the digital age and created unique artworks in which image and text deliver different layers of information.

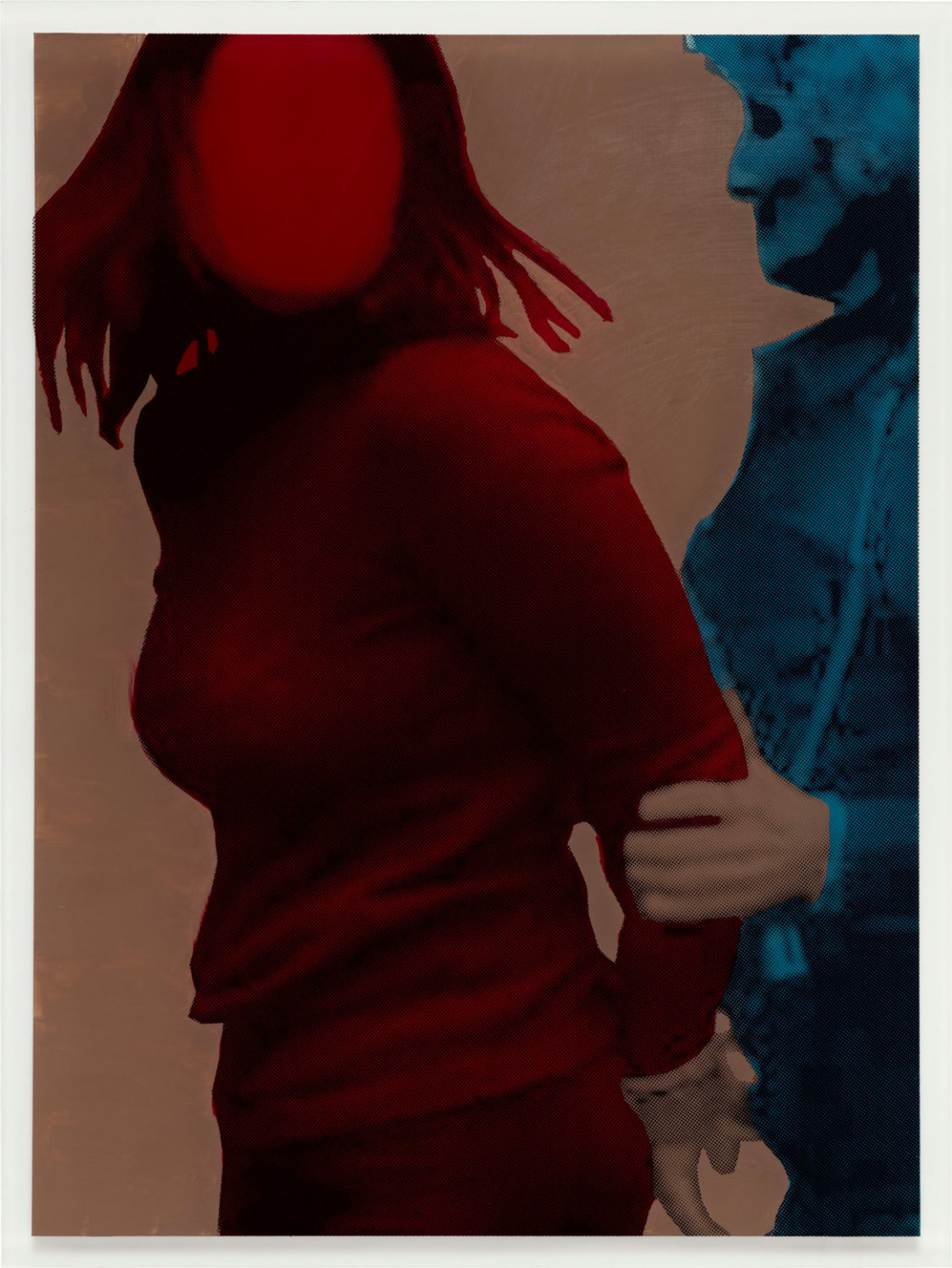

Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff has long been interested in what happens with images that are taken out of their original context and placed in an entirely different one – a phenomenon that nowadays happens in a completely uncontrolled manner every day and every second due to the enormous image production on social media. We can see her work as an appeal to pause and step into the reflective spaces that art has to offer. She formulated this clearly in an early text about contemporary art for teachers.[34] The appeal is also present in one of her most recent series, ”Oh Mother, What Have You Done” (2019 – 20), which is based on images depicting women being arrested, jailed, or detained that she has collected over a long period of time.[35] The images were produced by transferring the scanned and rasterized photographs onto plexiglass using UV ink and painting their backs in oil paint. Here, von Hausswolff has returned to the topic that she worked on so intensively in the early 1990s. She explores images of detained women and through the title also suggests that the works are about their role as, and in relation to, a mother. The women’s faces are erased or we see them from behind, so that their identities are hidden. The series is about vulnerable, broken, lonely women, as well as blaming and criticising a parent who has done something illegal. The interpretation of these intriguing works is open to the viewer’s projections.

As mentioned before, Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff has been invited to make a selection of work from the Moderna Museet collection for ”Alternative Secrecy”. The selection can be seen as an exhibition in an exhibition, as a reference point and background for her way of being inspired by and using other artworks and images in her own practice. With her well-trained eye she has chosen around fifty works, including the artists and photographers Rosa Becker, Larry Clark, Lisa Jonasson, Maria Lindberg, Irving Penn, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Oscar Gustaf Rejlander, Melissa Shook, Joel Sternfeld, Otmar Thormann, Gunnar Thorén, Brian Weil, Martha Wilson, Rolf Winquist, and Francesca Woodman. Works range from small albumen silver prints from the 1860s and a number of gelatin silver prints from the 1960s and 1970s, to large-scale C-prints from the 2000s – alongside other material such as screenprint, lithography, and acrylics. In short, work on paper, with some exceptions, like the sculpture ”Quilting” (1999) by Louise Bourgeois. In this catalogue, von Hausswolff has contributed a text in which she reflects on her selections and some of the artists’ oeuvres. She has also taken a look at the museum’s rich collection of film and chosen around twenty films and video pieces, most of them from the 1990s. Her own video piece ”Slap Happy” (1995), which she made together with her friend and colleague Lotta Antonsson, is also included.[36] Film has always been an important source of inspiration for von Hausswolff, and the method she uses in her own staged stills can be likened to the world of film, where fiction is constructed through strong characters and set design.

With her background as a photographer and her fixed place on the Nordic art scene, Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff has a unique dual position. When she embarked on her career, photography became contemporary art and one of the most cutting-edge media an artist could use.[37] At the same time this led the older generation of photographers, who worked artistically but within classic black-and-white photography, to be pushed into the background when it came to exhibitions and media attention. The situation was hotly debated in the photographic press when it came to, for example, which photographers got exposure at museums and other art institutions around the country. A similar development of photo-based art occurred in all the Nordic countries, which was naturally a result of what was happening internationally within contemporary art on the cusp between modernism and postmodernism.[38] This experience may have been more tangible among the women photographers of previous generations who were held back by the strong male culture in the photo industry, as well as the younger, acclaimed women artists who worked with photography. In recent years, we have once again witnessed changes in the medium, with artists, photographers, and activists working with different types of lens-based art and quickly disseminating their work via online exhibitions, digital magazines, different fora and networks, as well as through exhibitions and curated projections at photography festivals around the world.[39] The different traditions are starting to reconnect and the gap between photographic and artistic circles is nowadays not as big as in the early 1990s.[40] Another proof of this trend is that many younger photographers, as a reaction to digital technology, have become interested in and have begun using the older analogue technology in their practice. Many of them work with film and scan their negatives, which they then print digitally on different types of paper. This in turn has led to the oeuvres of many older photographers being rediscovered, collected, and presented in retrospective exhibitions at large art museums and different kinds of photographic institutions. [41] This also goes for many of the women photographers neglected in the history of photography.

Between 2007 and 2012, Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff was Adjunct Professor at the School of Photography in Gothenburg, and in 2016 she again became Adjunct Professor of Photography at Valand Academy at the University of Gothenburg.[42] As a teacher she has meant a lot to the younger generation of photographers who studied there. Thus, the circle closes. What von Hausswolff represents has now become established and the young generation moves on and explores their own world based on their own experiences and interests. One of the works that von Hausswolff is exhibiting for the first time in this exhibition is the gigantic ”The Body of Anthropocene” (2020), with a portrait of a worn, well-loved teddy bear with an abraded snout and grey fur. It refers to one of the most discussed terms of the recent years, the Anthropocene, which defines a new geological age.[43] We find ourselves in the age of humankind, where our effect on the planet is so enormous that it interferes with the fundamental parameters of existence. The toy implies a child’s perspective. It’s an object that doesn’t have any actual value, but that can provide a little child with a sense of security. Is it perhaps the case that all of humanity needs something to hold on to, a so-called transitional object in the form of a gigantic teddy bear, in order to cope with our uncertain future, including the threat of climate change, disease, and political restrictions? Once again, von Hausswolff has interpreted the times we live in in her own contemplative way.

Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff has also created a work out in the foyer of her exhibition at Moderna Museet – a wallpaper with images depicting holes. In 2008, she started her more systematic collection of images from the internet and other sources based on themes or particular image ideas, and holes became one such category. The Swedish song “Har vi inte grävt för många hål?” (Have We Not Dug Too Many Holes?) from 1985, written by Stry Terrarie from the band Babylon Blues, was another inspiration for the work. Here, she has created a photo essay, a story that is about penetrating deep into the human psyche. The hole could be a wound, a well, a grave, a bomb hole, or mysterious black holes in space: we can’t know for sure. The work will exist for the duration of the exhibition, from 23 October 2021 to 20 February 2022, and then be destroyed. The work might re-emerge in another form when the exhibition tours to Moderna Museet Malmö in the spring of 2022. The artist will let us know. It bears the title ”Excerpt from Alternative Secrecy”.

Notes

1. E-mail from Annika von Hausswolff to Anna Tellgren, 1 February 2020.

2. See e.g. Sören Engblom, ”Art in Sweden. Leaving the Empty Cube. Contemporary Swedish Art”, Stockholm: Svenska institutet, 1998; Folke Edwards, ”Från modernism till postmodernism. Svensk konst 1900 – 2000”, Lund: Bokförlaget Signum, 2000; Mårten Castenfors, ”Sveriges konst 1900-talet. Del 3. 1970 – 2000”, Stockholm: Sveriges Allmänna Konstförening, 2001; Sophie Allgårdh, ”Svensk konst i världen. Trender, lanseringar och reaktioner 1965 – 1996”, Stockholm: Carlssons Bokförlag, 2000; Sophie Allgårdh and Estelle af Malmborg, ”Svensk konst nu. 85 konstnärer födda efter 1960”, Sveriges Allmänna Konstförening’s annual no. 113, Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 2004; ”Konst och visuell kultur i Sverige 1810 – 2000”, ed. Lena Johannesson, Stockholm: Bokförlaget Signum, 2007. Annika von Hausswolff is mentioned in all of these books.

3. These four artists were the starting point of the study Anna Tellgren, “Fotografi och kön. Om den fotobaserade konsten under 1990-talet”, ”Från modernism till samtidskonst. Svenska kvinnliga konstnärer”, eds. Yvonne Eriksson and Anette Göthlund, Lund: Bokförlaget Signum, 2003, pp. 108 – 128.

4. See ”Implosion. A Postmodern Perspective”, eds. Lars Nittve and Margareta Helleberg, Moderna Museet exhibition catalogue no. 217, Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1987. An analysis of the exhibition can be found in Kristoffer Arvidsson’s ”Den romantiska postmodernismen. Konstkritiken och det romantiska i 1980- och 1990-talets svenska konst”, diss., Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg Studies in Art and Architecture no. 27, Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, 2008, pp. 133 – 162.

5. One of postmodernism’s most canonical texts is Jean-Francois Lyotard’s ”La condition postmoderne. Rapport sur le savoir”, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1979. See also ”Svar på frågan: Vad var det postmoderna?”, ed. Sven-Olov Wallenstein, Stockholm: Axl Books, 2011.

6. See for example Hal Foster, ”The Return of the Real. The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century”, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1996.

7. Some of the most important texts of the time are collected in the anthology ”The Contest of Meaning. Critical Histories of Photography”, ed. Richard Bolton, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1989. Writers include Benjamin Buchloh, Douglas Crimp, Rosalind Krauss, Christopher Phillips, Martha Rosler, Allan Sekula, and Abigail Solomon-Godeau. In Swedish there is the anthology ”Tankar om fotografi”, ed. Jan-Erik Lundström, Stockholm: Alfabeta, 1993.

8. Hans Hedberg (1954 – 2016). See Hans Hedberg, “Akademin för fotografi”, ”Tanken och handen. Konstfack 150 år”, Stockholm: Page One, 1994, pp. 168 – 189. See also the interview with Hans Hedberg, “The Lost Debate”, ”Nordic Now!”, eds. Camilla Kragelund, Hannamari Shakya, and Nina Strand, Aalto Photo Books, Helsinki: Musta Taide, 2013, pp. 157 – 158, and the collection of his published texts: ”Matter of Concern. Hans Hedberg Reader”, eds. Svante Larsson and Niclas Östlind, Stockholm: Art and Theory Publishing, 2017.

9. Tuija Lindström (1950 – 2017). See Tuija Lindström, ”Look at Us”, eds. Niclas Östlind and Lollo Fogelström, Liljevalchs catalogue no. 465, Stockholm: Liljevalchs konsthall, 2004.

10. Radium 226.05 was founded in 1983 by Carl Michael von Hausswolff (b. 1956) and Ulrich Hillebrand (b. 1953). Erik Pauser (b. 1957) joined them a bit later. It was located in a small commercial space on Husar Street in Haga, in which exhibitions were also hosted. It developed into a successful record label. See Håkan Nilsson, “Krig mot helheten. Phauss / Radium 226.05”, ”Omskakad spelplan. Konsten i Göteborg under 1980- och 1990-talet”, eds. Kristoffer Arvidsson and Jeff Werner, Skiascope 3, Gothenburg: Gothenburg Museum of Art, 2010, pp. 64 – 84.

11. Cortex was a rock band from Gothenburg that was active from 1980 to 1987. The leader and only constant member was Freddie Wadling (1951 – 2016). Annika von Hausswolff was a singer in the band from 1985 to 1987.

12. See Annika Öhrner, “After Post-Modernism. On Possible and Impossible Strategies in Swedish Contemporary Art”, ”The Moderna Exhibition 2006”, eds. John Peter Nilsson and Magdalena Malm, Moderna Museet exhibition catalogue no. 335, Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 2006, pp. 306 – 313.

13. For a description of the period see Niclas Östlind, ”Performing History. Photography in Sweden 1970 – 2014”, Malmö: Bokförlaget Arena, 2014.

14. For more information on Christer Strömholm (1918 – 2002) and the subjective tradition in Swedish photography, see Anna Tellgren, “In Memory of Myself”, ”Nordic Now!”, eds. Camilla Kragelund, Hannamari Shakya, and Nina Strand, Aalto Photo Books, Helsinki: Musta Taide, 2013, pp. 113 – 120.

15. Fotograficentrum (Centre of Photography) was founded in 1974 and was one of many centres that emerged in order to gather cultural workers within different fields. The national committee was located in Stockholm, but there were local branches in Gothenburg, Malmö, Uppsala, and Örebro, amongst others. In 1999 the organisation was taken over by the member-driven organization CFF – The Centre for Photography, which was founded by the Swedish Association of Professional Photographers (SFF).

16. The following artists were also included in the exhibition: Pelle Bergström, Helga Bu, Carl Hamilton, Annika von Hausswolff, Bengt-Olof Johansson, Annica Karlsson Rixon, Leif Lindberg, Mia Lockman-Lundgren, and Jan Svenungsson.

17. Hans Hedberg was the editor from 1990 to 1994. ”Index – Contemporary Scandinavian Images” changed name to ”Index – Contemporary Scandinavian Art and Culture” in 1996. It merged with ”Siksi: The Nordic Art Review” in 1999 to become the Nordic art magazine ”Nu: The Nordic Art Review”, which closed down in 2002. The portrait of a German shepherd, ”Eye Witness” (1995), is on the cover of ”Index”, no. 3 – 4, 1996. In the same edition is an article by Jeremy Millar, “Annika von Hausswolff”, ”Index – Contemporary Scandinavian Art and Culture”, no. 3 – 4, 1996, pp. 28 – 31. Her work ”The Legacy of Beige” (2002) was on the cover of ”Nu”, no. 1 – 2, 2002, which contained an article by Sara Arrhenius entitled “Annika von Hausswolff: Beyond the Limits of Reality”, ”Nu: The Nordic Art Review”, no. 1 – 2, 2002, pp. 46 – 65.

18. ”Equal To” was produced by the Swedish Association of Professional Photographers (SFF), in collaboration with Fotograficentrum, at Moderna Museet. Per B. Adolphson (SFF) and Karina Wärn (Fotograficentrum) were the exhibition managers. The curator was Iréne Berggren and the editor of the catalogue was Hans Hedberg. The catalogue was also published as a special edition by ”Fotograficentrums Bildtidning”, no. 2, 1991.

19. Fotografiska Museet (FM, The Museum of Photography) was founded in 1971 as a separate department within Moderna Museet. It existed up until 1998 when the collection of photography, after a reorganizing process, became an integrated part of the Moderna Museet collection and the name “Fotografiska Museet” was dropped. The private and commercial institution Fotografiska, which opened in 2010 on Stadsgårdshamnen in Stockholm, has no connection with Moderna Museet. See Anna Tellgren, “Photography and Art. On the Moderna Museet Collection of Photography from a Historic Perspective on the Institution”, ”The History Book. On Moderna Museet 1958 – 2008”, eds. Anna Tellgren and Martin Sundberg, Stockholm: Moderna Museet and Göttingen: Steidl, 2008, pp. 123 – 152.

20. The exhibition ”Index. Contemporary Swedish Photography” (1992) was compiled by Hans Hedberg and Jan-Erik Lundström. For the presentation of the concept see a double number of ”Fotograficentrums Bildtidning”, no. 4, 1991 / no. 1, 1992. ”Prospects. Contemporary Swedish Photography” (1994) was a touring version of ”Prospekt. Nyförvärv och visioner i 90-talet” (1993) at the Fotografiska Museet in Moderna Museet. It was compiled by Jan-Erik Lundström, who was the head of the Fotografiska Museet from 1992 to 1997. ”De utsatta. Nutida fotografi från Skandinavien” (1994) was also a touring exhibition, originally produced by Maria Lind and Jan-Erik Lundström, for the International Photographic Triennale (Pohjoinen Valokuva 1994) in Oulu. ”Stranger than Paradise. Contemporary Scandinavian Photography” (1994) was shown at the International Center of Photography in New York and was curated by Steven Henry Madoff together with Jan-Erik Lundström. For more about Nordic photography exhibitions see Anna Tellgren, “Darkness & Light. Contemporary Nordic Photography”, ”Katalog – Journal of Photography & Video”, no. 26.2, 2015, pp. 19 – 44.

21. The exhibition included work by Annika von Hausswolff, Maria Miesenberger, and Paulina Wallenberg Olsson. See the review by Towe Matre, “Metafor över krigets vanvett”, ”Svenska Dagbladet”, 7 September 1993.

22. This topic was taken up in an exhibition at Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall in Stockholm in 2000, in which photographs by the legendary police photographer Weegee (1899 – 1968) active in New York in the 1930s was shown together with work by Jane & Louise Wilson and Annika von Hausswolff. See Sara Arrhenius, “The Scene of the Crime. Annika von Hausswolff, Jane & Louise Wilson and Weegee”, ”Annika von Hausswolff, Jane & Louise Wilson, Weegee”, Stockholm: Magasin 3, 2000, pp. 11 – 17.

23. This is something that the art critic Lars O. Eriksson wrote about in an article in the series “Galleriet”, ”Dagens Nyheter”, 3 July 1994. He developed the topic further in Lars O. Eriksson, “Staying Power”, ”Konstperspektiv”, no. 4, 2002, pp. 18 – 23. This was also one of the main lines of thought in an essay by Maria Lind, “Annika von Hausswolff. The Thirsty Dog’s Image of Water”, ”Annika von Hausswolff, Knut Åsdam, Eija-Liisa Ahtila. End of Story”, ed. John Peter Nilsson, The Nordic Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia, Stockholm: Moderna Museet International Programme, 1999, pp. 10 – 33.

24. ”Nordisk Kriminalkrönika” was an annual that was published in Sweden between 1970 and 2016 by the Swedish publisher Svenska Polisidrottsförlaget, with newly solved cases and general articles about crime and how to solve it, as well as historically unsolved cases.

25. See ”Annika von Hausswolff in Dialogue with Sara Arrhenius”, Stockholm: Iaspis and Lund: Propexus, 2004, p. 19. It’s not entirely implausible that a first encounter with feminist theory was a number with the theme “Sex” by ”Fotograficentrums Bildtidning”, no. 4, 1990, with the guest editors Iréne Berggren, Marta Edling, and Eva Hallin. See also an article by Iréne Berggren, “Kvinnliga fotografer intar scenen”, ”Kvinnovetenskaplig tidskrift”, no. 3 – 4, 1993, pp. 85 – 94. This historiography was pursued further by Julia Tedroff, “Women Photographers in the Swedish Professional and Public Press 1930 – 2000. An Analytical Inventory”, ”Women Photographers. European Experience”, eds. Lena Johannesson and Gunilla Knape, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Gothenburg Studies in Art and Architecture no. 15, Gothenburg: Hasselblad Center, 2003, pp. 206 – 255.

26. An early example is the artist Martha Rosler’s project ”The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems” (1974 – 75) and her influential essay “In, around and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, ”3 Works”, Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design, 1981. Another example is Allan Sekula’s acclaimed project ”Fish Story” (1989 – 95), see Alla Sekula, ”Fish Story”, Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 1995.

27. Philosophical writing about the photographic image is vast and varied, but some classic texts in the field that have been immensely important include Roland Barthes, ”La chambre claire. Note sur la photographie”, Cahier du Cinéma, Paris: Gallimard, Seuil, 1980; Vilem Flusser, ”Für eine Philosophie der Fotografie”, Edition Flusser, Berlin: European Photography, 1999; Susan Sontag, ”On Photography”, London: Penguin Books, 1977. See also Geoffrey Batchen, ”Photography Degree Zero. Reflections on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida”, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2011.

28. One of the images, ”Försök att hålla ordning på tid och rum II” (1997), is one of the six photographs that were converted into postage stamps and issued by the post office Posten Frimärken under the title Photo Art on 21 March 2012. The other photographers whose work was included in the collection were Dawid (Björn Dawidsson), Denise Grünstein, Sune Jonsson, Gunnar Smoliansky, and Christer Strömholm.

29. “Samtal mellan David Neuman och Annika von Hausswolff”, ”Hjärnstorm”, no. 78, 2002, p. 36.

30. ”Annika von Hausswolff in Dialogue with Sara Arrhenius”, Stockholm: Iaspis and Lund: Propexus, 2004, p. 56. Hans Bellmer (1902 – 1975) was a German artist, known for the full-scale dolls he made in the mid-1930s, as well as his erotic photographs and drawings. He moved to Paris when the Nazis came to power and belonged to the surrealist circles there.

31. The work was donated to the Moderna Museet collection in 2011 in connection with the project ”Another Story”, where all of the museum’s nineteen galleries for the collection were filled with photography, see ”Another Story. Photography from the Moderna Museet Collection”, ed. Anna Tellgren, Stockholm: Moderna Museet and Göttingen: Steidl, 2011.

32. The first commercially viable instant film method was launched in 1947 by the inventor Edwin H. Land, who also founded the Polaroid corporation.

33. “Conversation between Annika von Hausswolff and Dragana Vujanović”, ”Grand Theory Hotel. Annika von Hausswolff”, ed. Dragana Vujanović, Gothenburg: Hasselblad Foundation and Stockholm: Art and Theory Publishing, 2016, pp. 55 – 56.

34. Annika von Hausswolff, “Vad som kännetecknar konst är inte givet …”, ”Konst är konst allt annat är allt annat. En skrift om samtidskonst Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff för lärare”, ed. Karin Malmquist, Stockholm: Lärarförbundet och Sollentuna: Edsvik konst och kultur, 1999, pp. 7 – 8.

35. The series was first exhibited in the exhibition ”I Woke Up Like This” with Cajsa von Zeipel and Annika von Hausswolff at Kristinehamn Art Museum in the summer of 2019, curated by Museum Director Andreas Brändström.

36. They used the pseudonym Anita & Anita when they worked on the video ”Slap Happy” (1995) and also did an assignment for the magazine ”Nöjesguiden” in the same period of time. Much later, in 2010, they had an exhibition at the art association Aura in Krognoshuset in Lund that was called “Anita”. The project Anita & Anita is completed.

37. See Charlotte Cotton, ”The Photograph as Contemporary Art”, New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004. This book includes Annika von Hausswolff among the 200 artists mentioned, as well as her Nordic colleagues Miriam Bäckström, Elina Brotherus, Esko Männikkö, Torbjörn Rødland, Trine Søndergaard, Vibeke Tandberg, and Mette Tronvold.

38. See Mette Sandbye, “Nordic (Art) Photography”, ”Nordic Now!”, eds. Camilla Kragelund, Hannamari Shakya, and Nina Strand, Aalto Photo Books, Helsinki: Musta Taide, 2013, pp. 7 – 13. About the Nordic art scene see also Jonas Ekeberg, ”Postnordisk. Den nordiske kunstscenen vekst og fall 1976 – 2016”, Oslo: Torpedo Press, 2019.

39. For different practices of showing photography, see the anthology ”Why Exhibit? Positions on Exhibiting Photographies”, eds. Anna-Kaisa Rastenberger and Iris Sikking, Amsterdam: Fw:Books, 2018.

40. One such example is the book ”Contemporary Swedish Photography”, ed. Estelle af Malmborg, Stockholm: Art and Theory Publishing, 2012. It contains articles about fifty-two photo graphers from different fields, including Christer Strömholm and Annika von Hausswolff. Annika von Hausswolff is also included in ”The Thames & Hudson Dictionary of Photography”, ed. Nathalie Herschdorfer, London: Thames & Hudson, 2015, pp. 196 – 197.

41. A number of highly interesting and innovative photo institutions were established in the last twenty years, including Le Bal in Paris, C / O Berlin Foundation in Berlin, Foam Photography Museum in Amsterdam, Fotomuseum Winterthur, and Arab Image Foundation in Beirut.

42. In 2012, the School of Photography (HFF) merged with Valand Academy, and on 1 January 2020 Valand Academy merged with HDK–Academy of Design and Crafts and became HDK -Valand – Academy of Art and Design at the University of Gothenburg.

43. The term “Anthropocene” was coined by chemist Paul Crutzen and marine biologist Eugene Stoermer in 2000. See Sverker Sörlin, ”Antropocen. En essä om människans tidsålder”, Stockholm: Weyler Förlag, 2018.