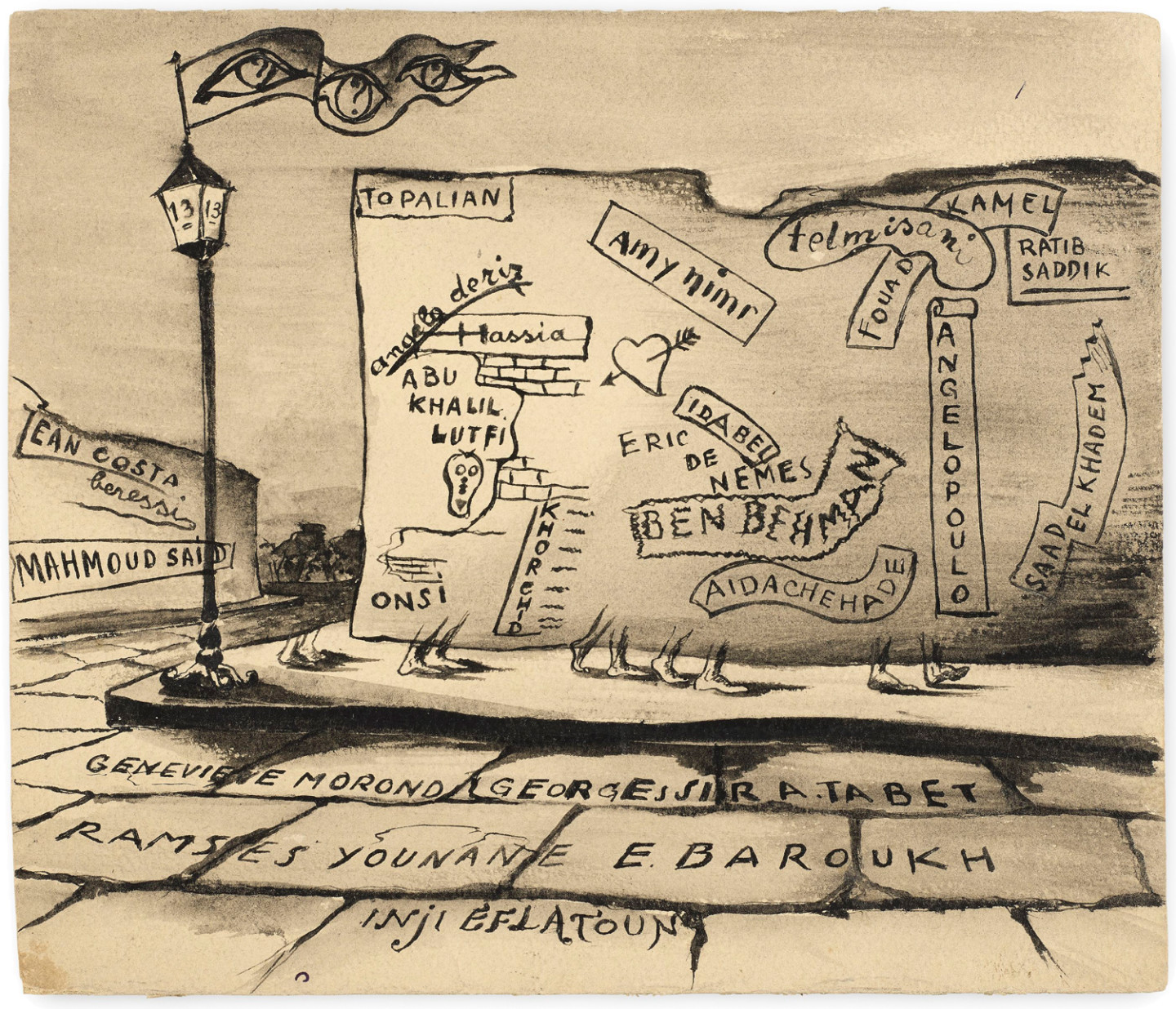

Art et Liberté group, ca 1945 Christophe Bouleau Collection

Background Art et Liberté

Founded on December 22, 1938 upon the publication of their manifesto Long Live Degenerate Art, the Group provided a restless generation of young artists, intellectuals and political activists with a heterogeneous platform for cultural and political reform. At the dawn of the Second World War and during Egypt’s colonial rule by the British Empire, Art et Liberté was globally engaged in its defiance of Fascism, Nationalism and Colonialism.

The Group played an active role within an international network of surrealist writers and artists. Through their own definition of surrealism, they achieved a contemporary literary and pictorial language that was as much globally engaged as it was rooted in local artistic and political concerns. This exhibition sheds new light on our understanding of modernism through Art et Liberté’s artistic contributions to the Surrealist movement.

The Permanent Revolution

By the late 1930s, when Art et Liberté emerged onto the Cairene arts scene, a state-endorsed culture of exhibition practices was firmly in place. The annual Salon du Caire that was organized by the highly conservative Société des amis de l’art attracted as many as 55,000 visitors in 1927. The state-endorsed salons enforced the classification of artists according to nationality.

Here it should be said that any American bootmaker’s advertisement is infinitely more moving than the most accomplished painting exhibited at the annual Salon du Caire ... These wretched people will never understand that painting is also a way of thinking, loving, hating, struggling, and living.” From the catalogue for the second Art et Liberté exhibition, 1941

In line with Surrealism’s rejection of the alignment of art with political propaganda, Art et Liberté rebelled against the conflation of art and national sentiment. They also rejected the notion of art for art’s sake whereby pictures had become a platform for the recycling of the same pictorial allegories and literary metaphors that did nothing to challenge the world. Some of Art et Liberté’s most polemical writing was directed against the artists who belonged to this camp, and who had become fundamental to a local canon that Art et Liberté would seek to reformulate, and even eliminate altogether.

In this hour, when the entire world cares for nothing but the voice of the cannons, we have found it our duty to provide a certain artistic current with the opportunity to express its freedom and its vitality.” Georges Henein, from the catalogue for the first Art et Liberté exhibition, 1940

The Voice of Cannons

Art et Liberté’s sense of liberty was augmented by the Fascist ideologies that, beyond their firm grip over Europe, had been on the rise in Egypt since the early 1930s. While Cairo was not on the frontlines of war, Egypt was nonetheless de facto at war by virtue of being under British Colonial rule. The country was obligated to put its national resources along with its entire infrastructure at the disposal of the British. By 1941, an overwhelming 140,000 soldiers were stationed in Cairo alone, and troops and tanks swarmed the city streets.

A profound engagement with the war, and the destruction that it caused, were leitmotifs across the whole spectrum of Art et Liberté’s work, including literature and caricatures. Surrealist depictions of battlefields and images of destruction capture the state of anxiety fuelled by the war. Several Art et Liberté members who encountered personal loss and displacement, reflected on their experiences through symbols of death and haunting images of the Apocalypse.

Surrealism presents a danger to our ever growing civilization which we must not ignore … We must fear it and fight it as we fear and fight communism, for any nation that accepts and encourages its development, is surely heading straight into the slime of moral decay.” Exhibition review of Art et Liberté’s second exhibition, The Egyptian Gazette, April 2, 1941

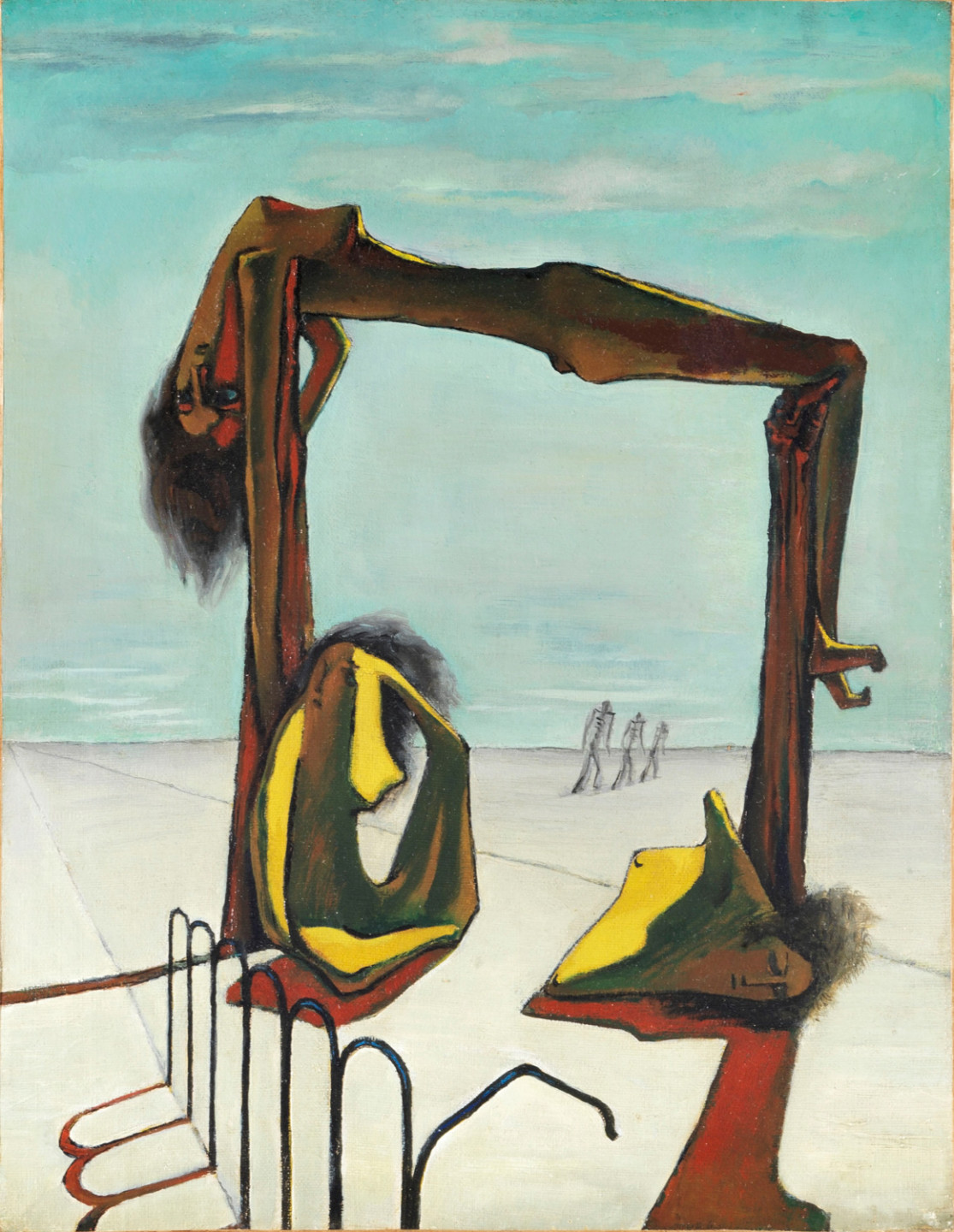

Fragmented Bodies

During the time of Art et Liberté, Cairo was a city marked by extreme economic inequality. The majority of wealth was held by a small percentage of feudal landowners and business magnates, while more than half of the population suffered from dire poverty. Art et Liberté believed that the unfair distribution of resources was due to the middle-class who obstructed societal progress. Revolution was therefore a necessary tool to destroy the hegemony of bourgeois mentality.

In line with Surrealism’s revolt against the bourgeoisie’s championing of Symbolism and Naturalism, the Group’s artists depicted the human body as fragmented in their paintings. In the traditional styles that they were opposed to, all characters were portrayed in an idealised fashion. Art et Liberté painted deformed, dismembered or distorted figures in order to poignantly illustrate the economic injustice that plagued their society.

Bildupphovsrätt 2018

The motif of the fragmented, or emaciated body, became a site of social as well as artistic protest. Art et Liberté portrayed the body in a state of anguish within violent settings. These gained in resonance given the simultaneous unfolding of World War II and the increased circulation of images of maimed soldiers and scenes of battles and destruction.

Subjective Realism

Art et Liberté believed that Surrealism was at its core a call for a social and moral revolution as well as an art movement. They coined a new term for Surrealism: Subjective Realism.

Writing in 1938, leading Art et Liberté theorist and painter Ramses Younane saw Surrealism as a movement in crisis, and differentiated two types of Surrealism. The first, best exemplified by Salvador Dali and René Magritte’s absurd juxtapositions, was considered excessively pre-meditated, leaving no space for the uncontrolled imagination. The second, consisting of automatic writing and drawing, was deemed too self-centred and not geared enough towards collective empowerment.

Younane identified the need for a new type of Surrealism, which he called Subjective Realism, by which artists deliberately incorporated recognizable symbols into works that were initially driven by the subconscious impulse. Kamel El-Telmisany, another Art et Liberté theorist and artist referred to this method as Free Art.

Group members used these two terms interchangeably as they sought to develop their own visual language. This new “collective mythology” as Younane described it, expressed with full lucidity the responsibility of the artist within his or her own society.

Among the Surrealist painters, one group is persuaded to direct all its efforts to the gathering of all things contradictory. Then there is ‘automatic drawing.’ […] Lastly, we propose ‘Subjective Realism’ where the objective elements and human elements are mixed, giving Surrealism a more profound and complete meaning.” Ramses Younane, ghayat al-rassam al-‘asry (The Objective of the Contemporary Artist), 1938

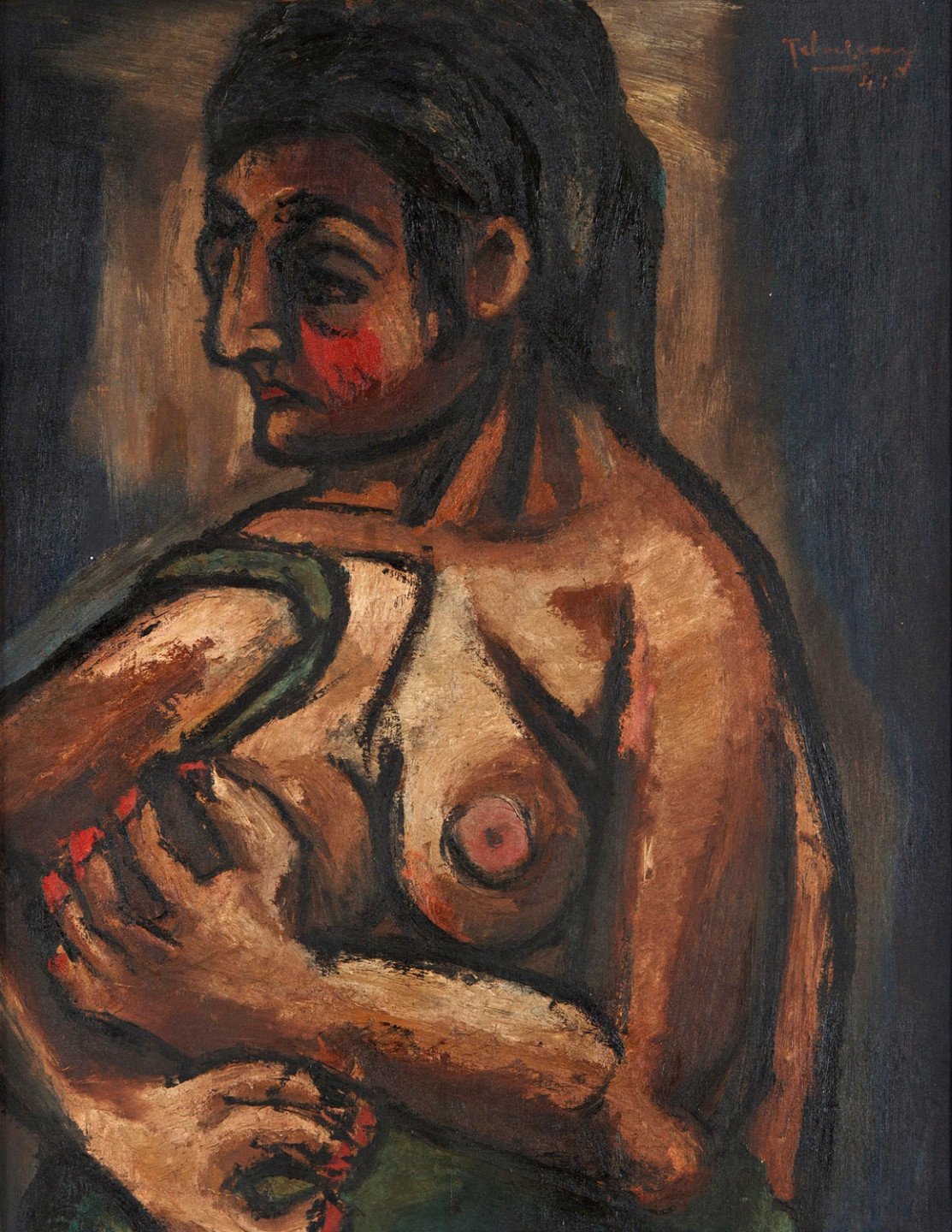

The Woman of the City

Several Art et Liberté leading patrons and artists were powerful women such as Amy Nimr, Marie Cavadia Riaz, and Lee Miller. Making use of their international networks, they played an essential part in introducing Surrealism to Egypt. Through vigorous salons that they hosted in their homes, they connected several Art et Liberté artists who they also supported financially. The active role that these pioneers played in shaping the group contributed to Art et Liberté’s strong feminist stand that was evident in many of their publications such as al-Tatawwur and Don Quichotte.

During the war years, due to severe poverty and the massive influx of soldiers, large amounts of women were driven into prostitution. The suffering prostitute, or the “woman of the city” as Georges Henein wrote in his poem St. Louis Blues, is a theme that is explored in a large number of Art et Liberté paintings.

The Group exposed the suffering of prostitutes by depicting them as solitary figures within surrealist settings, some pierced with nails while monster-like trees ravaged others. Unlike those surrealist practices where the dominant male gaze portrayed the female body as a sexual object, the Art et Liberté criticized the eroticization of women. The Group highlighted the conditions of the prostitutes by portraying them as objects that were trampled by male consumption.

“The voice of the woman of the city now

sounds across the horizon.

She says that she has an overwhelming

urge to see her river again.

She wants to explain to him the story of

these bracelets that burn her arms.

And the ardent insomnia that drains her

eyes and that would only go away with

the temptation of killing certain lovers

who can understand nothing other than her body.”

Georges Henein, “St. Louis Blues”,

Déraisons d’être, 1938

The Contemporary Art Group: An Egyptian Art

In 1946, some Art et Liberté members co-founded an independent collective under the name of Le groupe d’art contemporain (The Contemporary Art Group) that remained active until the mid-1950s. A few of the group members, such as Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar, Hamed Nada and Samir Rafi, would later become some of Egypt’s leading modern artists. The Contemporary Art Group diverted from Surrealism by predominantly using a local vernacular consisting of a symbolic iconography borrowed from popular arts and crafts.

In Egypt, there currently exist various artistic currents that aim to develop a national movement in art. It is not difficult to create an Egyptian national art if the artist understands our current special problems and traces them with the elements of modern environment and mentality.” Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar, “Vers un art spécifiquement égyptien”, Loisirs no. 21, Spring 1950

After the war, the question of how art can be made authentically Egyptian became a concern for artists and intellectuals alike. This was furthered by the Revolution of 1952, and the nation-building project that followed in its wake.

The Contemporary Art Group succeeded in being perceived by the public as a movement that invented the first truly Egyptian Art. The main artists of Art et Liberté, who had disbanded in 1948, saw the Contemporary Art Group as a mouthpiece for a new form of nationalism.

You all know those grayish bland kiosks that sometimes contain powerful transformers or high voltage cables, and on whose doors a brief inscription warns you, ‘Do not open: Danger of death’. Well! Surrealism is something on which a hand with countless fingers has written in response to the previous formula, ‘Please open: Danger of life.’” Georges Henein, Bilan du Mouvement Surréaliste, 1937

The Surrealist Photo

From the mid-1930s, Art et Liberté photographers such as Ida Kar, Hassia, Ramzi Zolqomah, Khorshid, and Van Leo made use of various techniques such as solarisation and photomontage, which had become central to surrealist photography. Lee Miller, who resided in Cairo from 1933 until 1939, worked closely with Art et Liberté and produced some of her most significant surrealist photography during that period.

The Group members created absurd images in which they further explored the deconstruction of the human form, and the alienation of the familiar within diverse types of surrealist settings. Similar to how other surrealist photographers employed primitive masks and objects in order to criticise the euro-centric colonial vision of the world, Art et Liberté used photography to criticise the nationalist exploitation of Pharaonic Egypt. They challenged the viewer’s familiar perception of ancient monuments and artefacts through playful compositions and absurd juxtapositions.

Georges Henein

The surrealist poet and provocateur Georges Henein played a central role in the founding of Art et Liberté. Born in Cairo in 1914 to an Egyptian diplomat father and an Egyptian-Italian anti-fascist mother, Henein experienced cosmopolitanism from a young age spending his early years between Egypt, Italy, Spain and France. He started introducing surrealist ideas to Egypt as early as 1934 through various publications, even before meeting the French Surrealist leader André Breton in Paris two years later. In 1936, Henein was among the signatories of La Vérité Sur Le Procès de Moscou, a declaration in response to the Moscow Trials against Trotsky by the Stalinist Communists.

Henein delivered his seminal lecture Bilan du Mouvement Surréaliste in Cairo on February 4, 1937, marking a quasi-official inauguration of the Surrealist movement in Egypt. This was followed on December 22, 1938 by the publication of Art et Liberté’s founding Manifesto Vive l’art dégénéré (Long Live Degenerate Art) to which Henein was the main contributor.

In 1947, Breton assigned him the secretariat of CAUSE, an international coalition for post-war surrealists. Henein’s loyalty to André Breton came to an end in 1948 due to increasing disagreements in vision. This rupture, along with increasing local political challenges ultimately led to the dissolution of Art et Liberté.

Writing with Pictures

One of the defining traits of Art et Liberté’s creative expression is the close correlation between their visual art and literature. Several of Georges Henein’s texts, for instance, were based on imagery derived from works by some of the Group painters such as Kamel El-Telmisany, Amy Nimr and Mayo. In turn, Henein’s surrealist poetry led to some of Art et Liberté’s most striking artworks by Inji Efflatoun and Ramses Younane. Equally so, Albert Cossery’s literary portrayal of poverty, provided several group painters such as Fouad Kamel, Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar and Robert Medley with rich subject matter.

Between 1939 and 1940, the Group produced three innovative journals: Don Quichotte in French, al-Tatawwur in Arabic and the bilingual bulletin Art et Liberté. From the early 1940s and into the mid-1950s they also ran two publishing houses, Les Éditions Masses and La Part du Sable, which disseminated writings of authors such as Albert Cossery, Edmond Jabès, Mounir Hafez, Yves Bonnefoy, Jean Grenier, Philippe Soupault, Gherasim Luca and Artur Lundkvist.

“Faiza was completely carried away

by the sudden tumult off her senses of

delirium … The flame of the candle

nearly out, produced a black smoke …”

Albert Cossery, La fille et le hashash, 1941