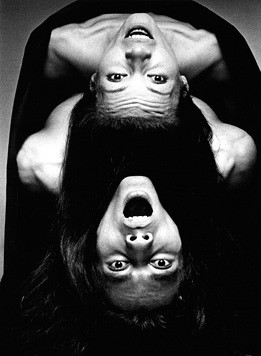

Jeanloup Sieff, Larrio Exon, Paris, 1976 © The Estate of Jeanloup Sieff, Paris

Jeanloup Sieff’s

Photographic formations

Text by: Anna Tellgren

He was commissioned by the fashion magazine Elle for portraits and short articles, and in 1958 joined the prestigious Magnum photo agency, before going back to freelance work the following year. One of his favourite subjects was portraits of French cinema and “la nouvelle vague” personalities, including Jean-Claude Brialy, François Truffaut and Jean Seberg.

In the 1960s, Sieff developed his fashion photography and worked extensively for Jardin des Modes. In his fashion and advertising photos the models are characteristically close to the pictorial surface, an effect achieved by using a wide-angle lens. His work method was based on physical and emotional closeness. This lack of distance makes his images exciting and visually interesting. Sieff made contacts in the USA and commuted with his cats between New York and Paris. He worked for the slightly more progressive American magazines Show, Glamour and Esquire, but above all for Harper’s Bazaar, after he became acquainted with its new editor, Marvin Israel. Photographically, this was an interesting period, when black-and-white photography was being challenged and began changing towards more personal styles and artistic projects. The Museum of Modern Art in New York features critically acclaimed exhibitions of photographers Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander and William Eggleston, influencing many young photographers and provoking discussions about the photographic medium.

Sieff discovered dance when he spent a few months at a photo school in Vevey, Switzerland, in 1953. One of the exercises happened to be “dance”. He became fascinated by the dancers’ long, lean bodies and muscles, the smell of perspiration and the shuffling sound of dance shoes across the floor. The young Jeanloup Sieff fell in love with these women, who resembled the sculptures of Giacometti – and they became his feminine ideal. Later, he was asked to illustrate a book about dance. This was his first book, J’aime la danse (1962), and it included an informative text on “le balletomane” by Jean Laurent. This assignment gave Sieff the opportunity to also meet and get to know some of the great dance stars, including Claire Motte and Rudolf Nureyev, who had just fled to the West. In his dance photographs, Sieff combines his sense of form, movement and body. But it was not the performances, where everything looked perfect, weightless and beautiful, that interested him. What he sought to capture was the daily routines of the dancers – the painful struggle to get their bodies to perform more or less impossible movements. In 1974, he photographed the American dancer and choreographer Carolyn Carlson for the magazine Réalités. The series presents her as an iridescent, almost unreal creature, both alluring and slightly disconcerting in her perfection. Their collaboration continued, and his documentation of Carolyn Carlson and her dancers during a modern dance workshop at the Paris Opera led to a performance where his photographs were projected as an accompaniment to the choreography. Dance became a perpetual theme throughout Sieff’s career, albeit more sporadically towards the end.

In the early 1970s, Jeanloup Sieff and German model Barbara started living together and had children. They travelled extensively, visiting Death Valley in California, for instance, where many of his fascinating landscapes were shot. In this series, roads, desert scenes, fields and beaches become beautiful and unexpected visual formations. Sieff began exhibiting his works and had a few major exhibitions at galleries. He won numerous awards for his photography over the years. This was an era when several of the legendary photographers were still alive, and many of them were his personal friends, including Jacques-Henri Lartigue. But it was also a pivotal point and photographers who had earned their living on assignments for popular illustrated and fashion magazines had to find new sources of income. Sieff, for instance, was responsible for a publication series, “Journal d’un voyage” for the publishers Denoël, to which he invited his colleagues Robert Doisneau, Duane Michals and Martine Franck to contribute.

It is only a short step from dance and fashion photography to nudes, and Sieff’s images expressing his love for women, bodies and photography were eventually compiled in the book Torses nus (1986). Shades enhance or shroud the shape of breasts and buttocks. The debate concerning the conventions and objectification of the female body in fashion photography is absent in Sieff’s own comments on his photography. His imagery is far from innocent, but he appears to have adopted the stance that he merely created something beautiful out of something he found to be very beautiful. The male models are also daring. The portrait of a nude Yves Saint Laurent from 1971, placed on a plinth like a Greek marble sculpture, is one of the most striking examples.

When Jeanloup Sieff summarised his career and his life after 40 years as a photographer, he reflected on the issue of art and photography. He had trouble accepting concepts such as “creative photography” and “vintage print”, along with the division of photography into commercial and private assignments. This is typical, however, of his generation, of his identity as a photographer, and of how the conditions surrounding photography had gradually changed after the war. The advertising and fashion industry stood for his income but also gave him great opportunities to travel, and to experiment and develop his own style and personal projects. Many of his best images originate in his commercial assignments and have been exhibited, purchased for photography collections and published in lavish photo books ever since the 1970s. They have become part of our history of photography.