Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun, 2015 Photo: courtesy of the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York © Hito Steyerl

More about the exhibition Manipulate the World

Dear Sophia,

I hope this finds you well. I would like to tell you about an exhibition that I am curating together with the artist duo Goldin + Senneby. The exhibition, titled Manipulate the World, is based on a long-term research project I have been conducting on the artist Öyvind Fahlström. What I am sending you here is an initial description of what we are working on, hoping to awaken your interest.

Manipulate the World is a contemporary group show that departs from four historical works by Öyvind Fahlström: the two large theatrical installations Dr. Schweitzer’s Last Mission (1964 – 66) and World Bank (1971), the Monopoly painting World Trade Monopoly (B, Large) (1970), and Mao-Hope March (1966), which is a film based on a public intervention. These works establish a playing field for the exhibition where Fahlström’s theatrical staging of fact and fantasy is returned in a contemporary “game” about politics and economy.

The exhibition is divided into two main spaces occupying the ground and bottom floors of the museum. The exhibition design on the entrance floor is directly linked to the idea of the game and to Fahlström’s World Trade Monopoly. The space is set up reminiscent of a board game where the audience walks around in a circular motion, just like in Monopoly. The other starting point on this floor is Dr. Schweitzer’s Last Mission. In this work, Fahlström gathered fragments of information and pictures that he put together in a big scenographic tableau. Even though the work is not strictly a game, its form brings to mind game pieces distributed on a surface where fact, fiction, irrationality, and psychedelic esotericism are mixed in a scenario with an open end.

The title refers to the German French theologian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Alfred Schweitzer whose missionary work in the field of medicine in Africa places the artwork within a postcolonial discourse that addresses the perception of a fixed historical narrative. In a way this work can be viewed as a model for the whole exhibition, which in a similar way seeks to put the theatrical in motion as a way of relating to the multiple possible “realities” inherent in the world we live in. How do we navigate information in the age of the Internet and big data, when the relationships between fact, truth, and fiction seem so fluid? How can an artwork today change our perception and manipulate the world?

The second part of the exhibition takes place in the windowless spaces downstairs. Here a staged depot of gold ingots – Öyvind Fahlström’s World Bank (1971) – is the center of a story about the distribution of money and power in the world. Taking its cue from Fahlström’s installation, this section of the show plays on the idea of a “hidden zone” and presents works relating to things that are normally veiled, obscured, withdrawn, or lurking beneath the surface.

The exhibition will include the work of around 25 contemporary artists who activate these ideas. In light of this, we have been following your work with great interest. We wonder if it would be possible for you to meet us and share some thoughts about your practice and how it may relate to what we are working on.

All the best,

Fredrik Liew

Dear Jill,

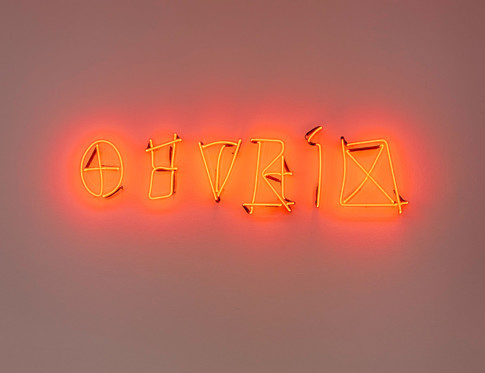

Yes, we want to see your armored Mercedes station wagon as part of a confrontation as one enters the exhibition. Here is the opening sequence we have in mind: The first work that greets one upon entering is a red neon sign, made by the Turkish artist Aslı Çavuşoğlu, based on found graffiti in Istanbul. Leftist protesters who oppose the regime often write “Devrim” (Revolution) on the city walls. However, nationalists are quickly there to add lines and scribbles, making the text illegible. Through this tense game of action, counter action, and manipulation, the exhibition is immediately launched into a direct relationship with ongoing political conflict.

Facing the neon sign, one finds oneself “squeezed” between two installations. To the left, your car and the accompanying elements of Failed States, which address notions of manipulation and paranoia. And to the right, a fake marble floor with mysterious stains on it reminds one of a crime scene. This work by Candice Lin is made out of two parts that are spatially detached from one another. The floor is in fact connected to a “laboratory” or “system” continuously generating a fermented liquid in another part of the exhibition. The liquid is carried through tubing that recalls a blood vessel.

We think it will be a very powerful start to the show.

Speak soon!

Fredrik

Dear Otobong,

Here are some further notes on the exhibition and also information about some of the projects it contains. I hope this will be useful in understanding why we are so eager to include a possible contribution by you. Please excuse the rather long e-mail.

As you already know, the title Manipulate the World comes from Öyvind Fahlström. It was the title of a text he wrote in 1964 about his invention of “variable paintings,” which were paintings with moveable elements. For instance, he painted on metal sheets and used painted magnets as pictorial elements on them. The magnets could be moved around, thus creating an ever-changing painting. The concept behind these works was to escape a static representation and instead create a situation where “everyone” could decide or “manipulate” the painting’s narrative and/or content. This was a model for how Fahlström related to politics and society. He approached reality not as something consensual and set in stone but as something that is in the making, produced by participation and play.

The exhibition follows in these footsteps. We approach manipulation as a means to produce/interfere/intervene/disrupt and question “reality” in all its forms and we aim to make an exhibition where artworks perform something beyond a mere representation of the world. We stay true to Fahlström’s use of the word manipulation as a creative force, and the idea that such a force can be employed to nurture a variety of visions – including unethical and illegal ones – is also present in the show.

This ambivalence of manipulation is for example evident in Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s work Earshot where he deploys aesthetics of evidence and the politics of sound and silence to uncover an illegal military manipulation of the truth. The installation is set up as a tribunal for an event that took place in the occupied West Bank ( Palestine ). In May 2014, Israeli soldiers shot and killed two teenagers, Nadeem Nawara and Mohamad Abu Daher. The human rights organization Defense for Children International contacted Forensic Architecture, which undertakes advanced architectural and media research. They worked with Abu Hamdan to investigate the incident further with the help of an existing sound recording. The case hinged upon an audio-ballistic analysis of the recorded gunshots to determine whether the soldiers had used rubber bullets, as they asserted, or broken the law by firing live ammunition at the two unarmed teenagers. A detailed acoustic analysis, for which Abu Hamdan used special techniques designed to visualize sound frequencies, established that the soldiers fired live rounds and, moreover, tried to disguise these fatal shots in order to make them sound as if they were rubber bullets. These visualizations later became the crucial piece of evidence that was picked up by the news channel CNN and other international news agencies, forcing Israel to renounce its original denial. The investigation was also presented before the US Congress as an example of Israel’s contravention of the American–Israeli arms agreement.

Another sequence in the exhibition that I believe may interest you is orchestrated between the equally process-based works of Ibrahim Mahama, Pratchaya Phinthong, and Katarina Pirak Sikku around the notions of land use and labor. Mahama covers the walls of a large room with jute sacks that have been used to transport goods, such as charcoal, coffee and cocoa, from his native Ghana to America and Europe, not least to the Nordic countries ( Finland and Sweden are actually the two countries in the world that consume the most coffee per capita). Mahama acquired these sacks by offering merchants new ones in exchange; hence they are both objects of and subjects in trade, silent witnesses to labor conditions, trade routes, and structures of postcolonial capitalist economy. Mahama’s installation outlines the exteriority of a contemporary geopolitical situation carrying on the postcolonial discussion raised in Fahlström’s Dr. Schweitzer’s Last Mission and the geo- economical debt and power relations that emanate from The World Bank.

Phinthong and Pirak Sikku’s works, both set in the rural north of Sweden, are placed inside Mahama’s installation. On a layover in Stockholm, Phinthong came across the news that migrant workers from his native Thailand were employed to pick berries under awful labor conditions in the vast wilderness of Sweden. Media reports in 2010 stated that thousands of berry pickers had traveled to Sweden in the hopes of earning a decent salary. Instead they found themselves tricked by the industry, paid up front to cover travel expenses and visas, only to be radically underpaid for their labor and forced to live in unhygienic lodgings in what was essentially a completely unregulated market within the Swedish welfare state. A Thai organization – Migrant Workers Union – reported that 80 percent of the Thai berry pickers returned to their country with larger debts than when they had left. The following year during a residency in Paris, Phinthong decided to travel to Sweden to work as a berry picker for two months. During this time he collected 549 kilos of berries for which he was paid 2 513 kronor (approximately 250 Euros) after deductions for gas and food. His project resulted in a series of works. In the exhibition we will present a hunting tower that he chopped down, his total earnings – he was paid daily in cash from an old safe – mounted in a frame, and a representation of the weight of the picked berries.

Pirak Sikku’s work departs from another fact about Sweden that may come as a surprise. In 2013, when Pirak Sikku made her work, Sweden held the world’s most attractive mining areas according to the public policy think tank Fraser Institute (today I believe Sweden have dropped to fourth place). Naturally the mining industry’s race for profit is unscrupulous when it comes to liability and responsibility. Effects on natural resources, cultural values, and the environment are taken lightly, as are the effects on the indigenous Sami people’s land use. In 2013 Pirak Sikku sided with activists protesting on site against the plans of yet another mine outside of Jokkmokk. When she heard the police were coming to disperse the protesters she put out a large piece of cloth on the ground, over which the police had to pass with their boots and vehicles to separate the crowd. The cloth not only bears witness to the events that took place above the ground but also became a frottage of the soil that was the subject of the conflict.

I believe that your work will enter into a very interesting dialogue with these and other projects. Thu Van Tran’s installation about rubber production in Vietnam also comes to mind. As in your own words: “There is no singular event. Everything is connected with everything. Noting down any event is just catching a glimpse, a fragment of time. What day is it today? Does it matter? The land has been there much longer anyway.”

I hope together we can find a way forward.

Yours sincerely,

Fredrik

Dear Pratchaya,

A quick update on the safe. We are still unable to find a perfect match

for the safe that appears in your photo. Attached are two images of safes

that come fairly close. The latest lead from an expert we have consulted,

Kent Karlsson from Pretect AB, is that it might be an “imported safe from

Asia made in the late 1990s”( ! ). We will start scanning the international

market, but it might not be so easy to find the exact same safe. If we have

no luck in our search, would a similar one be of any use at all?

Best, Fredrik

Dear Jonas,

We are still developing the area in between the two floors of the museum, making it a third exhibition space. The defining force we are working with to activate this area is Fahlström’s Mao-Hope March where he staged a picket demonstration down Fifth Avenue in New York. The demonstrators, who are not making use of any text or speech, are carrying pictures of the famous American comedian Bob Hope. However, there is one demonstrator amongst them who is holding an image of Mao Tse Tung. For the event Fahlström employed a radio reporter who went around and recorded the reactions and comments of the onlookers and passersby to this unexpected juxtaposition. At the same time he asked the people he met if they were happy. The recording of these conversations provides the soundtrack of the work.

The plan is to install Mao-Hope March at the bottom of the staircase, making the movement down the stairs a motion towards the march. It will be a meaningful connecting point between the two stories and naturally it makes sense to display the work in the public areas of the museum since it engages notions of “public space”. A series of other works that also address the “public domain” are also under way for this part of the show. It will already begin when you enter the museum: the communication of the show will be orchestrated by Detanico Lain, the furniture for the café and reading area was designed by Rivane Neuenschwander in an anthropophagia-like conversion of Swedish folklore design, and 10 percent of the revenue from the exhibition’s ticket sales will be invested in a market manipulation in a work by Goldin + Senneby. It is in this part of the exhibition that we would like to position your Geert Wilders work.

Best, Fredrik

Dear Núria,

I would like to continue our conversation regarding the placement of your work. As you know, we are thinking of activating your installation in the downstairs environment. This space is reminiscent of a basement in the museum ( I believe it was originally conceived as a series of photo galleries and therefore was constructed without windows and with a relatively low ceiling for more intimate formats). For our exhibition we have decided to emphasize this characteristic and create a space that resembles a storeroom. We think of it as the site of the hidden, repressed, and oppressed – from historical as well as judicial, political, and psychological perspectives.

The first room you enter will be designed with pallets that form the scenography and infrastructure of this part of the exhibition. The artworks will be installed in and around this system, which draws its inspiration from a work by Hanan Hilwé (head of the art collection of the United Arab Emirates) in collaboration with Walid Raad. The work Yet More Letters to the Reader consists of fifteen crates painted with “copies” of work from Erich Maria Remarque and Paulette Goddard’s collection, which was auctioned off in 1979 by Sothebys in New York, and is said to have been bought by Hilwé on behalf of the heads of state in Abu Dhabi. Apparently, it was also Hilwé who painted the crates.

This is a brief summary of Raad’s narrative: He met Hilwé when he asked to see the collection in 2014. She proceeded to tell him an incredible story of how she got rid of the works after Sheikh Zayed had criticized her for becoming “Westernized” and she herself had started doubting the “authenticity” of the artworks. After several unsuccessful attempts at giving away the collection – mysteriously the paintings always returned to their storage space in Abu Dhabi without anyone knowing how – she got advice from a cook who thought that the paintings were undead. She painted “copies” of the paintings on the crates hoping they would function as mirror images and thus frighten them away. Then she donated the paintings to the museum dedicated to the First World War in the Belgian town Ypern, near the place where the writer Erich Maria Remarque fought and was injured during the war.

In a similar way that Yet More Letters to the Reader suggests an “alternative history,” several works in this section of the exhibition propose counter actions to established orders and/or disorders. In her work unternehmen:bermuda Natascha Sadr Haghighian addresses the institutional and indeed commercial systems of the contemporary art world by playing with the relation between the power patrons (often disguised as philanthropists) and the artists.

In the spring of 2000, Sadr Haghighian was nominated for a prestigious art prize that is awarded by the Federation of German Industries. Instead of accepting the jury’s visit to her studio, she relocated the meeting to a new place: a bus stop in Berlin, situated in the middle of a triangle demarcated by three important institutions of art and science. During the meeting Sadr Haghighian delivered a lecture to the jury members, as well as supplying instructions to a series of actions. The entire situation was filmed and photographed by two “undercover agents” across the street. This material is presented in her work, together with a film that among other things narrates connections between the Bermuda triangle, Shakespeare’s The Tempest, the 16th century alchemist John Dee, and Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow-Up.

After the space with the pallets you will enter a vault-like room containing Öyvind Fahlström’s World Bank – an installation that he made in 1971 about the global market of natural resources, trade, loans, and debt. The work is based entirely on historical and economic data and set in a theatrical tableau “where the gold gleams in a dark room and where the political pressure applied by the World Bank to the Third World is illustrated by small silhouette figures and set-pieces on a stage of purple velvet” to use his own words.

We are thinking of installing your work on the wall that divides the storeroom from World Bank. The way Intervention # 1 relates to the bank Caja de Ahorro del Mediterráneo’s purchasing of homes on auction at 50 percent of the appraised value (and after first evicting its inhabitants) mirrors strategies presented in Fahlström’s work. Also, your action of employing the evicted mason to remove the doors of the homes that the bank acquired and guaranteeing him impunity through the legal identity of the cooperation relate to the counter manipulation strategies also found in the works of Hilwé/ Raad and Sadr Haghighian.

Excuse me for going on and on about the exhibition. But I must add that the theme of financial speculation brought to the surface in your work doesn’t stop with Fahlström’s World Bank. In a third room in the “basement” we will set up a Bitcoin mine as the main protagonist in Nicholas Mangan’s Limits to Growth, an installation that is a live economic “ecosystem” referring to the history of currencies: their invention, their manipulation and their forgery. The mine is directly connected to the power supply and Ethernet in the museum and hence becomes materially and metaphorically attached to the hosting institution. Similarly, as I have mentioned to you before, Goldin + Senneby are working on a project that plays with the museum infrastructure in relation to the financial system of stock market speculation, betting part of the income from the exhibition’s ticket sales in a short-selling attack. In case the investment is successful the profit will benefit the museum in the form of a gift with special conditions.

On the topic of manipulation there is hardly any subject matter more suitable than the world of finance. It is almost impossible to think of anything that is independent of this architecture of risk. Even if you want to withdraw from financial speculation completely, you are not able to: globally banks and indeed the world economy rely on it, Swedish pension money is invested and even our museum is partly funded as an extension of such speculation.

Your work will undoubtedly be an important addition to the exhibition.

My very best,

Fredrik

Dear Hito,

We are very happy that your installation will soon be ready for installation in the museum. We would also like to thank you very much for your valuable contribution to the catalog. As you know, the idea of the game is central to our project, so the question that forms the title of your text, Why Games?, is very poignant. Please let me take the opportunity to introduce some of the other writers in the book – together with all the artists in the exhibition they contribute towards answering your rhetorical question.

Barnabás Bencsik has written a text about the globalized industry of political manipulation through the story of the American spin-doctor Arthur J. Finkelstein and his role in Israel and Eastern Europe. Bencsik’s narrative is told through the particular case study of his native Hungary. María Berríos is writing about Operation Truth, an international counter-information strategy to defend the Chilean revolution from the attacks of the reactionary national and international press, and about the related establishment of the Museum of Solidarity Salvador Allende, of which Öyvind Fahlström was a part. “Can art and the museum be a weapon?” is one of Berrío’s questions (which calls to mind your question “is the museum a battlefield?”). My co-curators Goldin + Senneby and their collaborator Katie Kitamura are also contributing with a text that refers to their work in the show, Zero Magic, and running through the catalog is an interactive comic by the artist Olivia Plender, created especially for this book.

In connection to the release of the catalog we are also publishing two books especially dedicated to the work of Öyvind Fahlström. Scholar Jesper Olsson has written about the important series of works titled Ade-Ledic-Nander that Fahlström produced between 1955 and 1957, and professor Pamela M. Lee has authored a book about Fahlström’s Monopoly games from the early 1970s.

Yours sincerely,

Fredrik Liew

P.S. We have now finalised our list of participating artists for the exhibition: Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Rossella Biscotti, Juan Castillo, Aslı Çavuşoğlu, Kajsa Dahlberg, Detanico Lain, Economic Space Agency, Róza El-Hassan, Harun Farocki, Öyvind Fahlström, Goldin+Senneby, Núria Güell, Candice Lin, Jill Magid, Ibrahim Mahama, Nicholas Mangan, Sirous Namazi, Rivane Neuenschwander, Otobong Nkanga, Sondra Perry, Pratchaya Phinthong, Katarina Pirak Sikku, Natascha Sadr Haghighian, Jonas Staal, Hito Steyerl, Hanan Hilwé in collaboration with Walid Raad, Thu Van Tran, Alexander Vaindorf, Wermke / Leinkauf.

The catalogue Manipulate the World – Connecting Öyvind Fahlström is available in the Shop and the Webshop from 21 October.