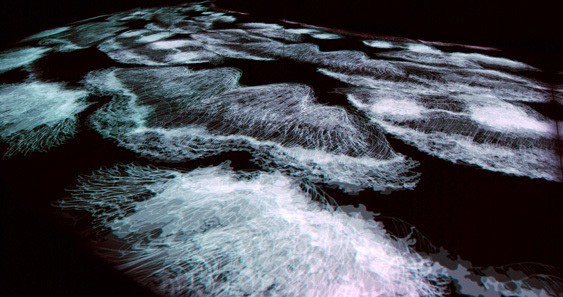

Tabaimo, midnight sea, 2006/2008 © Tabaimo/Courtesy of Gallery Koyanagi & James Cohan Gallery

About the exhibition

Tabaimo began working with film as a medium when she discovered that individual images were not adequate in relating her narratives. Today, she creates suites comprising hundreds of drawings, which she scans in and processes digitally into animations. The resulting films are often shown as installations, projected in well-defined spaces or a stage setting into which the audience is conducted. Only in that encounter, Tabaimo claims, can the work be completed. When the outsider’s gaze meets her often profoundly personal images, investing them with his or her own associations and meanings.

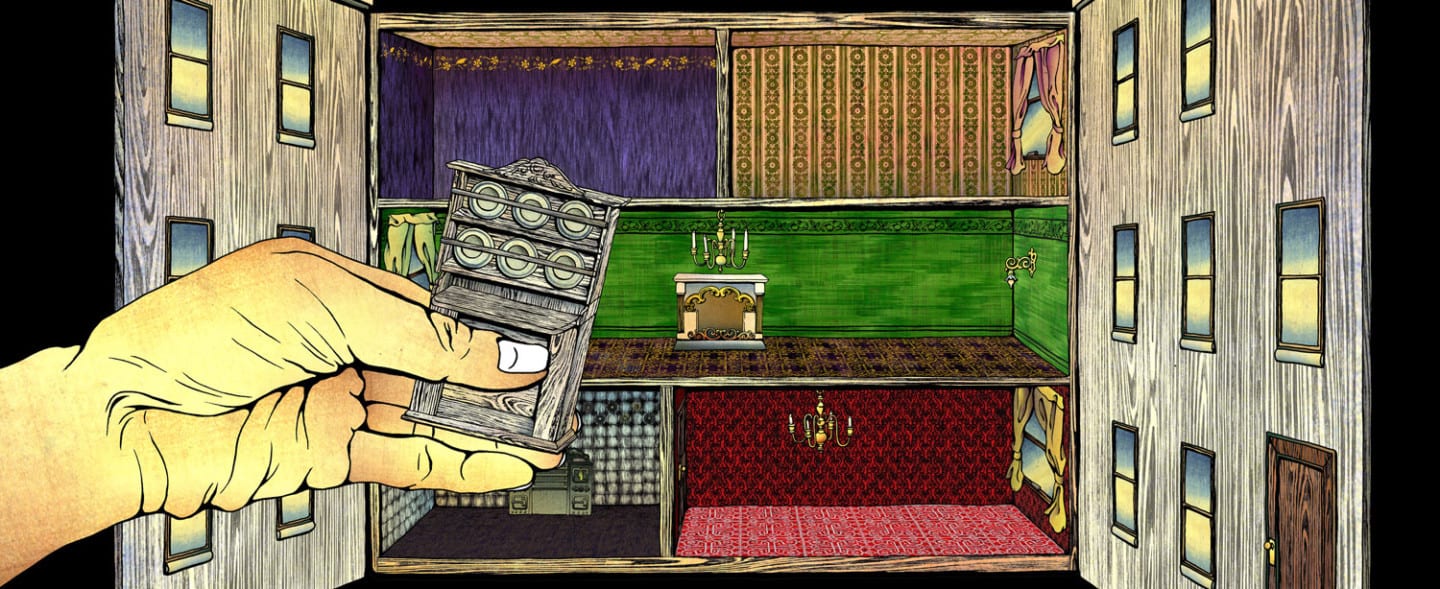

In her works, events and characters are driven towards the absurd, the comical and occasionally the grotesque, as in dolefullhouse (2007), where the facade of a doll’s house is opened and we are shown how a pair of hands systematically furnishes the rooms in a western bourgeois style. The rooms become increasingly cosy and orderly, until the calm is infiltrated by an unwelcome presence, and the hands grow more agitated and restless before finally tearing away at the interiors, revealing a frightening physicality. Factually and detached, an everyday situation dissolves into gory violence and magic realism, with a pinch of slapstick.

Tabaimo’s imagery is inspired by and contrasts against contemporary Japanese anime as well as a rich tradition of woodcuts. The lines and colours are clearly inspired by the 17th-20th century masters, but also the choice of subject matter. Tabaimo often sets her chamber dramas in contemporary urban environments, such as the commuter train, the apartment or the street crossing. A peak in the tradition of the Japanese woodcut is Ukiyo-e, literally “pictures from the floating world”, where artists such as Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1848) described contemporary pastimes and everyday life in prints that were spread in large editions. On the whole the pictures pandered to the tastes of an urban audience with an interest in social interaction and renderings of domestic culture and nature. A not insignificant genre, however, focused on more spectacular motifs, including sexual relations or violent scenes.

midnight sea (2006/2008) presents a stylised nocturnal maritime landscape, suggesting Hokusai or perhaps Hiroshi Sugimoto’s (b 1948) photographic Seascapes. Waves intersect the black ocean surface in an ancient Japanese metaphor for skin, body and ageing. In the deep, among intestine-like kelp and seaweed, kaminoke – here, demonic creatures or spells – are moving, like repressed impulses haunting a tormented subconscious.

Tabaimo creates a timeless and virtually abstract environment without any real narrative, which appears to contrast completely with the acute contemporary tableaux, also in its lack of colour. We are presented with the image of an existence in perpetual flux, at the overhanging risk of being thrown off balance at any time, with devastating consequences. As in several of Tabaimo’s works, the personal and the collective seem to merge, in no hierarchical order.

public conVENience (2006; VEN is Japanese for “public”) is set in a public ladies’ lavatory, a paradoxically intimate and anonymous facility. Here, women pass each other among the thin-walled cubicles without interaction or dialogue, and only the onlooker is presented with a totality. A schoolgirl has taken off her uniform and ceremoniously prepares for an afternoon on the town. A woman who stumbles into a cubicle painfully gives birth through her nose. The infant is later flushed down one of the toilets on the back of a turtle, a reference to the fable of a man who saved the life of a turtle and was rewarded with a visit to a kingdom under the sea. Graffiti appears on the walls spontaneously, and the reflections in the row of mirrors appear to lead their own life. The insistent moths recur again and again, documenting everything that happens with their eyes that have been replaced with camera shutters.

The work can be interpreted as an allegory on the Internet. On line, in front of the computer screen, it is easy to feel beyond reach, with the voyeur’s sense of control and distance. But in fact, Tabaimo states, we are simultaneously submerged by a wave of impressions and disinformation. We end up in situations we would never normally put ourselves in, and experience a purely fictitious seclusion, when we are in fact under constant monitoring.

public conVENience features that sharp social satire and media critique that is often found in Tabaimo’s work. Employing surrealism and abstraction, she wishes to capture a reality we rarely meet otherwise, in this case through a spectrum of female experiences and fantasies, concealed from the eyes of society. On the news, human fates are reduced to touched up images, stripped of all personal sordidness, which, in their matter-of-factness become entirely unreal. In the media we are fed the opinions of the establishment presented as imperative and placard-like truths. But the public domain and “general public”, Tabaimo claims, can ultimately refer only to ourselves.