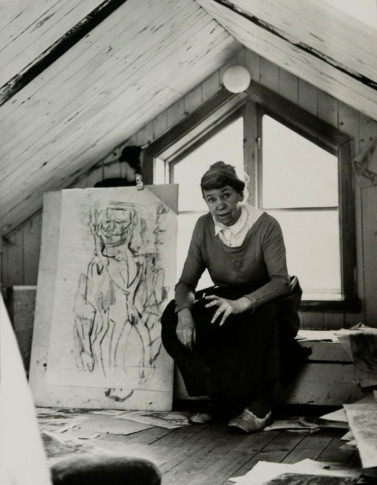

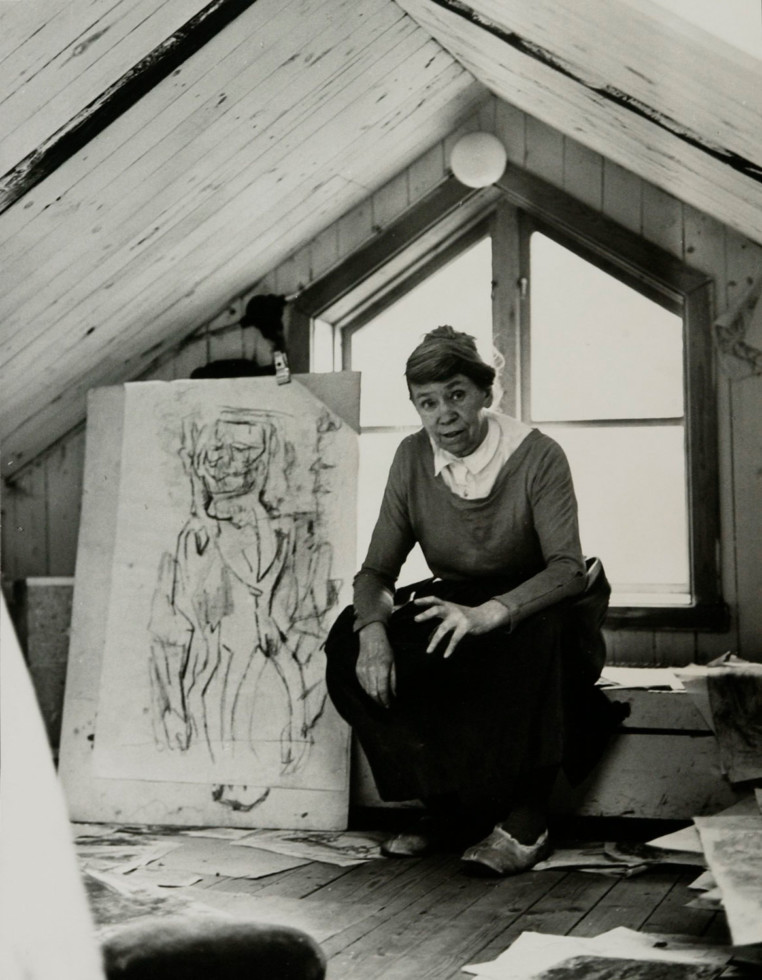

Siri Derkert © Photo: Anna Riwkin

Biography Siri Derkert

Preparations

Derkert knew early on that she wanted to be an artist and, supported by her family, she began preparatory studies at the Caleb Althin art school when she was 16 years old. In 1911 she enrolled as a student in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (now the Royal Institute of Art) in Stockholm. The school had difficulties accommodating the new ideas which were spreading over Europe and which in various ways had reached the students. During her short time at the Academy, major differences of opinion arose between students and teachers concerning teaching and views of art.

Girls and boys were taught separately. Siri Derkert organized a protest against the rule that female students were prohibited from drawing nude male models. She forged strong bonds of friendship with other students such as Anna Petrus, Ninnan Santesson, and Lisa Bergstrand, which continued to be very important for them throughout their lives. When Siri Derkert left the Academy in the summer of 1913 there were scarcely any female students left.

Parisian avant-garde

In November, 1913 Siri Derkert arrived in Paris and rented a large studio in the middle of Montparnasse, which was financed by Anna Petrus. A lively community of artists lived in this quarter just before the First World War, with many artists from Russia and Europe. There were several private academies and Siri Derkert visited both Académie Russe and Académie de la Grande Chaumière.

Derkert discovered Paris together with her friends from the Royal Academy, Ninnan Santesson and Lisa Bergstrand, who were students of Antoine Bourdelle. The three explored the city and its museums; they sewed their own clothes after the Paris fashions; they socialized with Nordic artist circles and enjoyed organizing parties. They also encountered new painting in the Autumn Salon in 1913 and in other exhibitions. The young Finland- Swedish artist, Ivan Lönnberg, took them to Picasso’s dealer, Wilhelm von Uhde, where they probably saw the Spaniard’s work, which had not yet been widely exhibited.

Siri Derkert’s own work was tentative. She was trying to find her own artistic language and spent a great deal of time drawing. Few pieces are preserved from this initial stay in Paris – one is the woodcut, Modellen (The Model). After travelling with Santesson and Bergstrand to Algeria and falling in love with Valle Rosenberg in the spring of 1914, Derkert left Paris in June of the same year.

Algeria

Siri Derkert, Lisa Bergstrand and Ninnan Santesson were invited by a Swedish engineer to borrow a house in Algiers. They decided to accept the offer and went to Algeria in February, 1914. They stayed for five weeks and the experience had great significance for Derkert’s artistic development. She was deeply struck by her encounters with people, landscapes and with a different, unfamiliar culture. Derkert translated these encounters into paintings.

The three friends set up a studio in the house and engaged local models. In the paintings from Algeria, figures and their surroundings often meld together in rich forms and colour combinations. Several studies portray an exotic view of the local people. A major part of Derkert’s work from Algeria was later stolen, but a number of water-colours and also oils, probably produced in Paris, remain.

Around the turn-of-the-century, it was popular to travel from Europe to North Africa in order to venture upon an unknown and exotic part of the world. Several artists travelled there, but the exotic motifs favoured by Swedish artists at the time were often recreated in their studios at home or in Paris. Photographs show how Derkert, Bergstrand and Santesson experienced an unusual sense of freedom of movement. Siri Derkert’s period in Algeria comprises a singular and important example of female Swedish artists’ journeys to Africa.

Valle Rosenberg

Leaving Algeria, Derkert returned to Paris in March 1914, where she met Valle Rosenberg, an artist from Borgå in Finland, who was active in artists’ circles in Montparnasse. Charismatic and with contacts in the Paris art scene, Rosenberg tried to make a living by his paintings. The two artists fell deeply in love.

Much later, Siri Derkert was to comment that “One didn’t need to hear the rumours of what an extremely gifted painter he was to be interested in V.R. He was the first man I met who was interested in – even admired – his female colleagues as professionals. The first man who in discussions on art, literature or social issues, didn’t come with the usual platitudes.”

In 1914 Siri Derkert posed as model for Rosenberg’s Damporträtt (Portrait of a Woman). During the summer of the same year, they spent a few happy weeks together in Harrogate in England. They painted and created masquerade costumes until the outbreak of the First World War, when they went separately to Stockholm. Around Christmas 1914, they realized that Derkert was pregnant, whereupon they left Stockholm and travelled around southern Italy during the spring of 1915. Here Derkert painted her first cubist studies, a suite depicting the Italian landscape. Their son Carl Valdemar (Carlo) was born on 1 July 1915 in Naples. The couple’s respective families and friends were not informed of this event.

The Intima Theatre, Bertil Lybeck

A year after the birth of Carlos, Derkert and Rosenberg’s funds ran out. They left their son with an Italian family and travelled to Stockholm intending to exhibit their paintings. However, Rosenberg, a Finnish citizen with a Russian passport, got no further than Paris. An intensive exchange of letters followed. In Stockholm Derkert renewed contacts with her family and her female colleagues and probably produced the epic, cubic paintings that today are only known through photographs.

In May, 1917, Anna Petrus, Märta Kuylenstierna and Siri Derkert set up a dance performance at the Intima Theatre in Stockholm. To the newspaper, Svenska Dagbladet, they stated: “We want the dance to be a work of art, which people can enjoy. Just as we try to express things in painting or sculpture, we are trying to do that in dance.” The critics especially noted the costumes, which were designed by Derkert, inspired by Valle Rosenberg’s sketches that had been sent from Italy. However, the reuniting of Rosenberg and Derkert seemed increasingly remote and difficult. Rosenberg’s life in Italy for a period of two years, starting in late autumn 1917, was largely unknown to Derkert and to posterity.

During the summer of 1917, Derkert met the artist Bertil Lybeck, whom she had known in Paris. Their daughter, Liv, was born in April 1918 in Copenhagen, her birth kept secret from family and friends. A sister, Sara, was born in March 1920 in the same city. Derkert continued to experiment in watercolours and oils, several of these paintings reflecting her uncertain, vulnerable situation at the time.

Fashion

Siri Derkert’s costumes for the Intima Theatre in 1917 were discovered by Birgitta Glantzberg, the director of the fashion house, Birgittaskolan, in Stockholm. In the following years Derkert was commissioned to design several winter and summer collections for Birgittaskolan and she regularly travelled to Paris on its behalf. Some thirty water-colour drawings remain which, with timely elegance, show her feeling for colour and proportion. The cut and models are influenced by Valle Rosenberg’s ideas, described in both letters and sketches. Birgittaskolan went bankrupt in 1921 and Siri Derkert suffered economic losses.

Valle Rosenberg, who periodically lived with his son Carlo in Italy, was destitute. In the autumn of 1919, all Russian nationals were deported from Italy. Very ill with malaria and tuberculosis, Rosenberg was shipped off in a cold freight car. On his way through Stockholm, he met up with Siri Derkert, who long afterwards related: “When I met him on his arrival in Stockholm he was in good humour, but ill. Thinking only to be able to eat, rest and get well, so he can begin to work again with whatever will pay. At some point perhaps he can begin to paint again. He was very reticent about his time in Rome.” Rosenberg continued on to his home in Borgå, Finland, where he died in a sanatorium in December, 1919.

Denmark, 1920s

Derkert’s ambition to exhibit her cubist paintings was realized first in 1919 when they were included in Den fri udstilling (The Free Exhibition) in Copenhagen and later the same year, also in Lund. In 1921 they were shown in the Aprilutställningen (April Exhibition) at Liljevalchs Konsthall in Stockholm. Despite a positive reception from the press, it took decades before Derkert’s cubist work achieved a distinctive place in Swedish art.

During the 1920s, bitter reality caught up with Siri Derkert. She found it difficult to establish herself on the art scene and her relationship with Lybeck ended. Nevertheless, they remain married from 1921 to 1923 in order to make their daughters legitimate. Derkert’s three children were then in foster homes in Italy and Denmark. Carlo and his two sisters were fetched home at different times; in practice Derkert supported the family by herself.

During this period Derkert worked for Birgittaskolan until the fashion house went bankrupt in 1921. She also travelled to Paris as fashion reporter for the magazine Idun and produced illustrations for fashion articles in Bonniers veckotidning (Bonniers’ Weekly Magazine). She wrote a feature column for the newspaper Dagens Nyheter under the signature, “The Blonde Lady”, which humorously depicted the vulnerable position of women in culture. In addition, she set about learning the technique of making miniatures and her miniature portraits were shown in the Stockholm World Fair in 1930. At this time Derkert lacked lodgings of her own so she and her children lived alternatively with her sisters, with her own parents, and during the winters, in different rented the summer houses in the Stockholm archipelago.

The incredible reality

Siri Derkert acquired her first permanent dwelling in 1931 when her mother Valborg bought “Lillstugan” (Little Cottage) on the island of Lidingö. Here in this erstwhile bakery and its garden she created her later work. Derkert investigated what she called “incredible reality” – everyday life and people in her immediate surroundings. As models she had her own children, the children of local farm labourers and children of families spending the summer in northern Roslagen. Her selfportraits often record strong spatial and existential atmosphere and moods.

In conjunction with the showing of her children’s portraits at her first solo exhibition at the Swedish-French Art Gallery in Stockholm in 1932, a critic described Derkert as the “evangelist of unconditional ugliness in modern art”. Her major breakthrough came first in 1944, with a solo exhibition at the galleries Gösta Stenman and Stenman’s Daughter in Stockholm. The press basically reviewed the same motif of children: “Siri Derkert’s major exhibition flows like hot lava from an exploding volcano through the two floors. […] I wonder if the child in Swedish art has ever been painted with such burning insight and feeling. […] Painting that is expressionism in the correct sense of the word.”

Derkert’s daughter Liv also developed a singular artistic style. In November 1936, mother and daughter travelled together to Paris and studied there until April, 1937. In May of the same year, Liv became ill with tuberculosis and died in November, 1938.

Fogelstad

Siri Derkert was burdened with grief for several years after her daughter’s death in 1938. However, she started to attend courses at Fredshögskolan (a school fostering independence and responsibility and thereby promoting the cause of peace) and as of the summer of 1943, she made annual visits to the Fogelstad Women’s School in Sörmland. Both of these schools offered classes in history and psychology. Fogelstad also offered political science and practical citizenship education. These studies broke the ice, restoring Derkert’s creative vitality and igniting her spirit.

In a large number of drawings, Derkert portrayed the leading women at Fogelstad – for example, Honorine Hermelin, Elisabeth Tamm, Elin Wägner and Emilia Fogelklou. They had all been involved in the early movement for women’s suffrage. Even though they were often politically more conservative than Siri Derkert, her association with them during her visits to Fogelstad meant that she could see more clearly the connections creating women’s vulnerability. The portraits are at once deeply private and political. The process that was initiated here led to Derkert’s later public works. She also drew course participants singing in the Fogelstad choir. In the drawing the women meld together into a body with a thousand legs, in an image of the female collective.

Siri Derkert became more and more politically engaged. She was connected to Clarté, the left-socialist organization, and as of 1950, she was chairwoman of the Swedish Women’s Left Association, Stockholm section. In the article “Woman – means or goal?”, published in 1948 in the paper, Ny Dag (New Day), Derkert delivered crushing criticism of the reactionary values concerning the woman’s role in the home, which according to Derkert, permeated the state enquiry Betänkande angående familjeliv och hemarbete (Household Work Enquiry) from the same year.

Art and politics

In the 1950s, Siri Derkert returned to explicit political comments in her work. As she herself became a more and more public figure, with more and more attention from the media, clippings from newspapers on environmental damage and other current events began to crop up in her paintings. Her new collages recall her early cubism, but with the difference that now texts are given more prominence and their meaning adds a significant dimension to the work. She also produced several images in the form of placards, either as original models for posters as in the painting Amnesty International, or as lithographs, where pictorial motifs and slogans interact.

Portraits were also part of this work. They included drawings of friends such as the radical art critic, P.O. Zennström or as mixed media collages like that depicting the plant physiologist and professor, Georg Borgström, who early on issued warnings about the misuse of the world’s resources. She also continued to return to the self-portrait.

During these years Siri Derkert avidly engaged in experimentation. In addition to traditional techniques such as drawing and painting, she used spray paint, band-iron, paper and plaster in collages. The piece Matriarkatets död (Death of the Matriarchy) even contains other materials – the skeleton of a perch over a woman’s body in terracotta.

Public space

Siri Derkert’s first work for public space was Kvinnopelaren (The Female Pillar), which was unveiled in 1958 at T-centralen (the central underground station) in Stockholm. On two sides of the pillar, carvings done in moist concrete depict “Images from the Struggle of Ideas” – portraits of Fogelstad women and the authors, Thomas Thorild, Jonas Love Almqvist and August Strindberg. On the two other sides of the pillar are images of women’s everyday life, children playing, women conductors, women hodcarriers (brick-bearers) and women rowers, the “Rower madams” (women who ferried passengers between the islands in the Stockholm archipelago in the 19th and early 20th century).

In 1959 Derkert won a commission for decorating a wall in the boardinghouse for pupils at Anundsjöbygden’s lower secondary school in Bredbyn. She worked for several years on this project, with sketches in the form of collages, developing a theme around Senapsträdet och himlens fåglar (The Mustard Tree and the Birds of Heaven). The finished piece, consisting of 21 coloured concrete slabs, was never erected at the school, but can be seen today in the Kulturhus in Skövde.

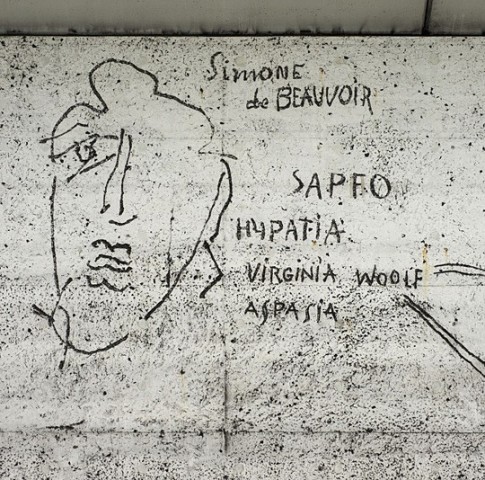

Derkert’s Ristningar i naturbetong (Carvings in Natural Concrete) in the underground station at Östermalmstorg is, because of its size and complexity, one of the most innovative pieces of public art in post-war Sweden. The personal continues to be interwoven with the political through a 145 meterlong composition with drawings of figures, portraits, texts and music notation. Thematically, the piece revolves around peace, environmental questions, dance, music and rhythm. The music, from The Marseillaise and The Internationale, as well as the placement of the piece in one of Stockholm’s most high bourgeois quarters, made it controversial and meant that when it was unveiled in 1965, it incited lively debate – as it continues to do. Siri Derkert also worked with textiles in cooperation with The Friends of Handicrafts. Her large tapestry, Vad sjunger fåglarna???? (What are the Birds Singing????) from 1965 was produced for the assembly hall in Höganäs Town Hall.

The new avant-garde

Throughout her adult life, Siri Derkert participated in various ways in the broad political and medial discourse. In the beginning of the 1960s, she entered into yet another interesting sphere – the new avant-garde. Her cubist work attracted little interest in the 1910s, but the “cubist”, Siri Derkert, was launched in conjunction with her retrospective at Moderna Museet in 1960. The museum’s director, Pontus Hultén, the critic Ulf Linde and, not least, the curator, Carlo Derkert, her son, gathered together to highlight and celebrate her work. Derkert’s vital contemporary art, with its roots in the Parisian avant-garde of the 1910s, is a vigorous exponent of the modernity and modernism that the museum would wish to be associated with.

Siri Derkert, at the age of 74, was chosen to represent Sweden at the first exhibition in the newly-built Nordic pavilion at the Venice Biennial in 1962. Early cubist painting – but primarily, her large collages, originating in the sketches for Senapsträdet och himlens fåglar, were shown at Venice. Several of these collages are now destroyed. Also shown were fragments with angel motifs, stars, birds in almost ethereal compositions, where Derkert’s interest in environmental themes is combined with and reinforces an almost spiritual theme. Her Biennial exhibition was highly regarded and returned her art to the avant-garde – where it originated but had not been given a place.