The 1st at Moderna: El Perro

1.2 2007 – 18.3 2007

Stockholm

When the Gulf War broke out in 1990, this view changed. The American television network CNN, in particular, framed the war with spectacular graphics and viewer-adapted dramaturgy in which military operations were shown on prime time television. Many questioned the war reporting. The violence seemed unreal – like a staged spectacle. Did the military adapt their operations to the television coverage?

War and propaganda are intimately connected. This has been analysed by Paul Virilio in his 1989 book, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception. Just like the Chinese general Sun Tzu pointed out 2,400 years ago in his book The Art of War, Virilio states that wars are not only won on the battlefield. They are also won by having advance knowledge of your adversary’s plans, and by persuading your own soldiers to risk their lives for their country. Among other things, Virilio explores the close relationship between Hollywood and the American military during the Second World War. By constructing and fomenting a sentimental patriotism in box-office films, people were influenced in a direction that suited the powers that be. Hollywood made money; the military got its soldiers.

Since the Gulf War, the alliance of the media with the political powers has become more apparent and universally called into question. Following their first exhibition in 1991 in Madrid, the Spanish artist group El Perro (Pablo España, Iván López, and Ramón Mateos) have explored social conditions in society, often departing from the relationship between the media and the political powers. They have frequently returned to the significance of violence in this relationship. When they participated in last year’s group exhibition “ARS 06” at Kiasma in Helsinki, they showed their construction “Security on Site”. A kind of panic room where you could take refuge if you felt threatened, it was an attempt to address the problem of the sense of an increasing threat. But what kind of threat? Direct physical threats, to be sure, but I suspect that El Perro also points to the anguished feelings inside of us which are not a reaction to a concrete threat but rather originate in the media reports of violence, diseases or natural catastrophes. The media tend to exaggerate and even speculate in tragic events. What exactly is it that makes us worried – the actual events or the reporting of these events?

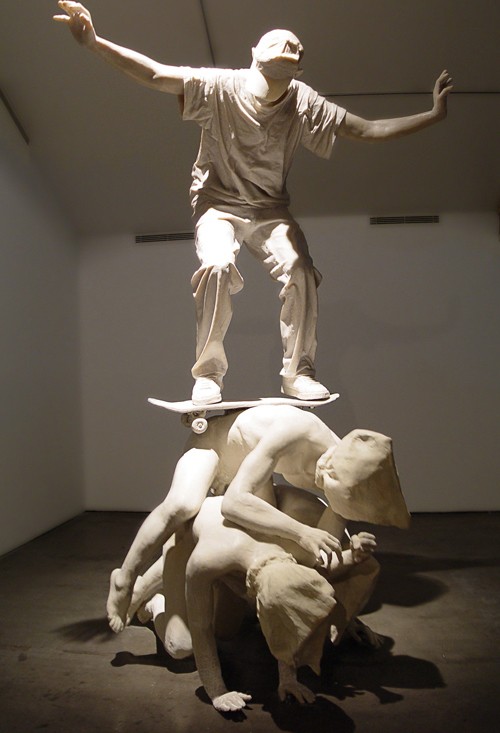

When I first saw the group’s sculpture “Memorial (Serie Democracia)” (2005) I felt as if I had seen it before. But I had not. What I recognised was the infamous pictures of prisoners who in 2004 were humiliated in the prison camp Abu Ghraib in Iraq by being forced to form a human pyramid. These are despicable pictures, and despicable acts. The baroque-style sculpture shows three naked, hooded prisoners on the floor. This was the media image I recognised. But there is a figure balancing on their backs. A skateboarder!?

The three artists of El Perro (Pablo España and Iván López also collaborate under the name Democracia, and Ramón Mateos exhibits under his own name) have a background in Spanish subcultures, particularly the skateboard culture with its connection to graffiti and post-punk. In the video “Skating Carabanchel” (2005), which is screened in conjunction with the sculpture, one sees three skilful skateboarders performing tricks in the notorious Madrid prison Carabanchel that held the most hardened opponents to the Franco regime after the Spanish Civil War. Today it is abandoned and littered with broken bottles and graffiti.

By displaying the two works together, El Perro appears to point to the fact that the violations in Iraq equal the oppression and the injustices committed by the Franco regime in Spain. If you scrutinise the video, you will see a skateboarder balancing with perfect equilibrium, much like the figure in the sculpture. The connection between the prisons and the skateboard culture is not immediately apparent. The skateboard culture originates in a liberty-spirited rejection of the establishment. But how, then, can a skateboarder outrage the prisoners, or perform tricks in an old torture prison?

There is no simple answer. The first thing you think about is that the skateboarder represents popular culture – guileless and history-less. But “Memorial (Serie Democracia)” also depicts a kind of amalgamation of contradictions generated by the information bombardment of our time. In a sense, the sculpture is rather tasteless, which also applies to our mass media society. El Perro also points to the fact that war images have become a part of the entertainment industry.

It is no exaggeration to say that our view of the world has been replaced by that of the mass media. But it’s nothing new. When Andy Warhol produced his series of silkscreens depicting Jacqueline Kennedy mourning the murder of her husband in 1964, he modelled his series on a newspaper picture. When asked by a reporter if he was trying to depict the murder of the American president, Warhol answered no. Did his images show the grief of Jacqueline Kennedy? No. What, then, were the pictures about, the reporter asked. Andy Warhol answered laconically, They are about how the mass media is mourning for us.

What Warhol identified with his 1960s work was how the mass media images had become a screen between us and reality. But that is not all. When an image is reproduced innumerable times it runs the risk of losing its original meaning. When postmodernism entered the art scene in the 1980s this development was read both in a positive and a negative way. The positive was the possibility of viewing art as a set of signs, like a language, which could be formulated and reformulated in all possible and impossible combinations. What is original and what is copy became unimportant. What was important was the effect, or influence, of the signs or the language – not what the signs originally meant.

Preview

Opening 1 Feb 2007 6-8 pm Location: In the corridor outside the collection 01:1. At 6.15 pm conversation between the artists and John Peter Nilsson, curator at Moderna Museet. Only the Main entrance is open, the rest of the museum is closed. Language: English

This exhibition has also been generously supported by SEACEX (State Corporation for Spanish Cultural Action Abroad).

The 1st at Moderna is an exhibition programme for contemporary art. The opening is always on the first day of the month, and the exhibitions are in different venues in or outside the museum.