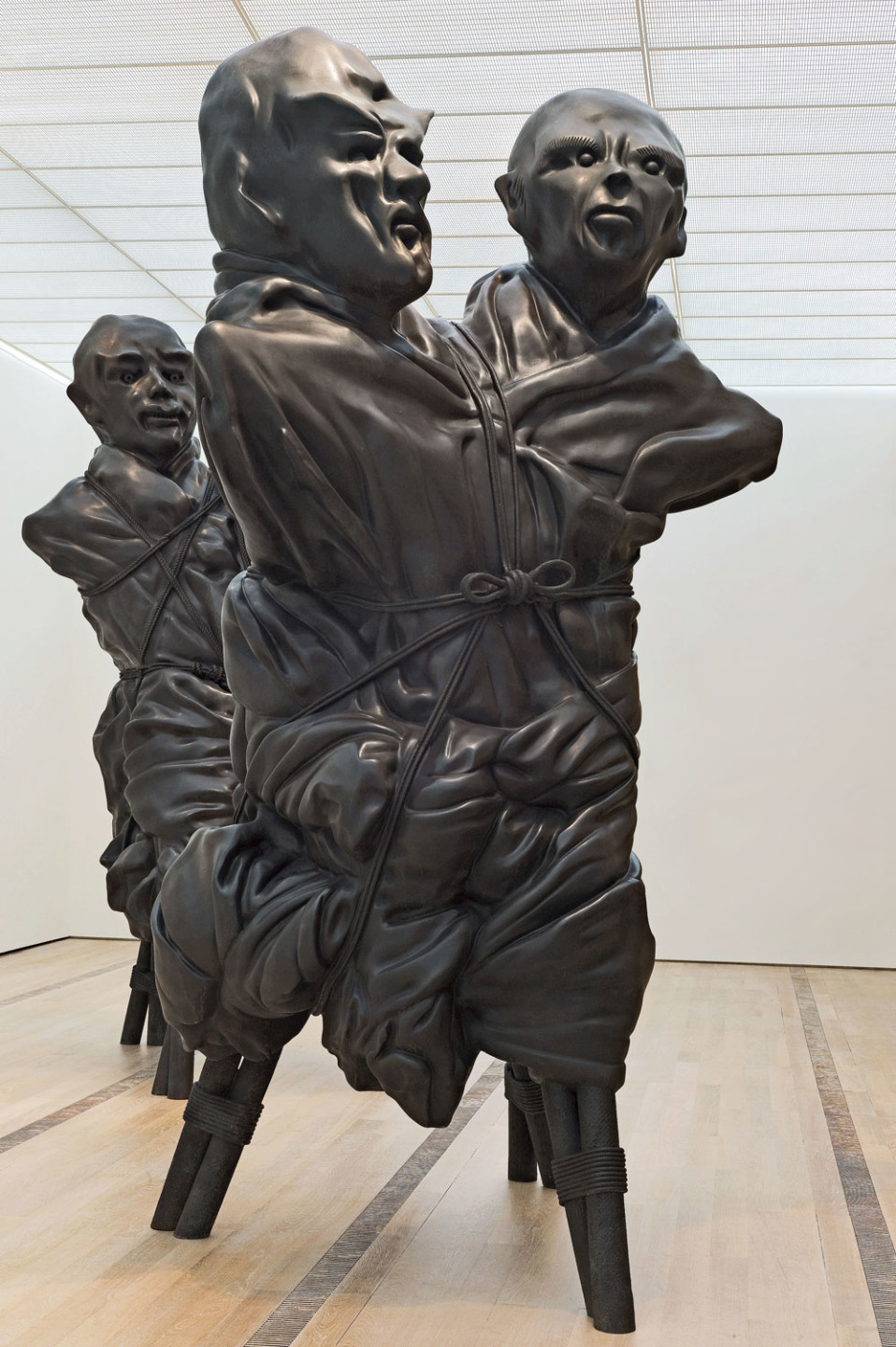

Thomas Schütte, Vater Staat, 2010 Photo: Åsa Lundén/Moderna Museet © Thomas Schütte / Bildupphovsrätt 2016

Before the Law

Essay by Daniel Birnbaum

Thus begins the parable by Franz Kafka known as “Before the Law”. Although it forms part of the novel The Trial, it was published separately in a Jewish weekly during Kafka’s lifetime. Before the Law was also the title of a major exhibition at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne a few years ago. That was where I first encountered Thomas Schütte’s unforgettable sculpture Vater Staat (Father State, 2010), an imposing figure in rust-coloured steel, considerably larger than a human being. Who is he – a high priest or a king, an imam or a figure out of legend and myth? Someone very distinguished and with great authority in any case, hardly someone you would scurry past without stopping. Nor someone you would try to negotiate, compromise or bargain with.

His robe falls in deep folds, tied with a belt around his waist. His headdress is very plain and projects a kind of archaic spirituality. A straight-backed figure – imperturbable, unbending, incorruptible. He is strikingly immobile and stable and very far from being meek and accommodating. It seems impossible to conceive of him as anything other than a man of firm principle. Or rather more than that: in some way he represents principle itself, the Law. When you move in closer, you become aware that there is a refined and sensitive cast to his features. Despite the way he radiates power, despite that obvious force, he is not frightening. The force he has is not violence and brutality. There is a kind of gentle repose to his features, a redemptive quality. He feels, or so I imagine, sympathy for us humans. But is he a human being himself?

He is currently to be found on Exercisplan, as the area in front of Moderna Museet is called, standing guard over the entry to the permanent collection and to the exhibition in which many other figures – some small and playful, others large and menacing – are on show in the museum’s halls. At an early stage in his career, Schütte was creating figures of a kind that call to mind puppets or marionettes on a stage. This began on the small scale with works whose starting point was the nature of the human being and the infinite variation of our facial expressions. At the beginning of the 1990s, he was showing paired figures beneath small domes of glass, the figures tied together in couples – united in struggle and bound together in intimate enmity. Work on this series would then continue with a radical shift in scale and using different materials and entirely different physical dimensions: a visitor to the Museum of Modern Art in New York in recent years can hardly have missed the great battle that United Enemies continue to wage in the sculpture garden.

When you move in closer, you become aware that there is a refined and sensitive cast to his features. Despite the way he radiates power, despite that obvious force, he is not frightening. The force he has is not violence and brutality. There is a kind of gentle repose to his features, a redemptive quality. He feels, or so I imagine, sympathy for us humans. But is he a human being himself?

A slightly more peaceful couple had, however, been produced a few years earlier in the shape of With Tears in My Ears (1989). Here, the couple is involved in a sacred or ceremonial activity in a space that is only alluded to (anyone at all can see that it is a table turned upside down) but which nevertheless calls to mind a kind of temple. In spite of the small scale of this work, which forms part of the Moderna Museet collection, it anticipates much of what we are being shown nowadays in the most magnificent of Schütte’s largescale sculptures. And yet these figures also appear to be involved in some kind of speculative activity, some form of reflection. Side by side, like at a wedding, they are standing before a mirror that, seen from their perspective, is towering over them like a wall. But are they looking at themselves?

In the most fantastical piece of writing about puppets in the whole of German literature, “Über das Marionettentheater” (On the Marionette Theatre, 1810), Heinrich von Kleist puts forward the notion of the superiority of the dance of the marionette, infinitely more graceful than anything a human being, inhibited by consciousness, is capable of. He or she who has eaten of the fruit of the tree of knowledge – and therefore possesses the capacity for reflection and self-awareness – can no longer move with the artless unconsciousness of a child or like a puppet suspended on strings. The limbs of the marionette are not burdened by gravity; they do not labour under the limitations imposed by the human mind. Can we humans, asks Kleist’s principal character, ever achieve that kind of perfection, can we ever attain that artless paradise? No, the way back to such innocence is closed. We have been doomed, as it were, to be conscious. However, Kleist would not be a Romantic if he were not prepared to open another door, one that opens onto infinite awareness. Our only option is the step into total reflection, an infinite awareness where the condition of the marionette and of God coincide. Although this would be, as Kleist points out, “the last chapter in the history of the world”.

There is no shortage of fantasies and speculative thinking in philosophy and mythology concerning an era in which Man overcomes his own nature and is reunited with his animal side. In Christian manuscripts describing the state of affairs after the Last Judgement, when the righteous will live together in a new form of harmony, these only partly human creatures are occasionally shown as having the heads of animals. This could perhaps be interpreted as a return to the innocence that Kleist discovered in the dancing of children and puppets. We are presented with puppets in Schütte’s art. Sometimes they are inconspicuous in size, sometimes they are frighteningly large. More recently we have also been presented with impressive animals. And yet we never entirely leave behind the oppressive and familiar everyday life we all share. His figures have not been liberated in the slightest from the meanness and shoddiness we are continually confronted with in the media and in politics. Vater Staat may radiate a kind of sublime sympathy, maybe even benevolence, but there are other figures behind him who lust for power and are completely without scruples: villains and swindlers, criminals whose intentions are ill-concealed. One would rather not know where the three efficient-looking and menacing metal men in Efficiency Men (2005) are headed or what their intentions are. Schütte’s faces may from time to time express a childish innocence, but just as often he shows us features that have grown hard and are hungry for power.

Like the man before the law, we find ourselves on the threshold. There is nothing to obstruct our passage, we have only to step straight ahead. Although once we have crossed over, law and order are not all that we may sense:

“Because the gate to the law stands open, as always, and the gatekeeper steps to the side, so the man bends forward in order to see in through the gate. When the gatekeeper notices this, he laughs and says: – If you find it so tempting, just try going inside despite my prohibition. But remember: I am powerful. And I am only the least of the gatekeepers. From room to room you will encounter one gatekeeper after the other, each more powerful than the last. Even I cannot endure the mere sight of the third.”

The text is written by Daniel Birnbaum, Museum Director, and is published in the exhibition cataloge Thomas Schütte: United Enemies.