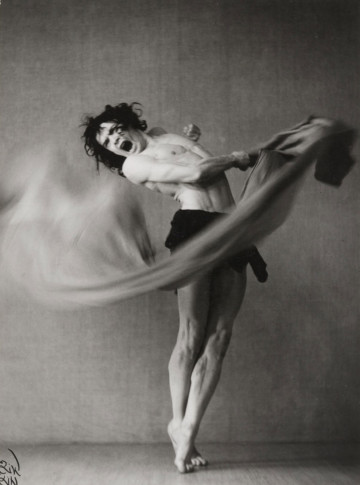

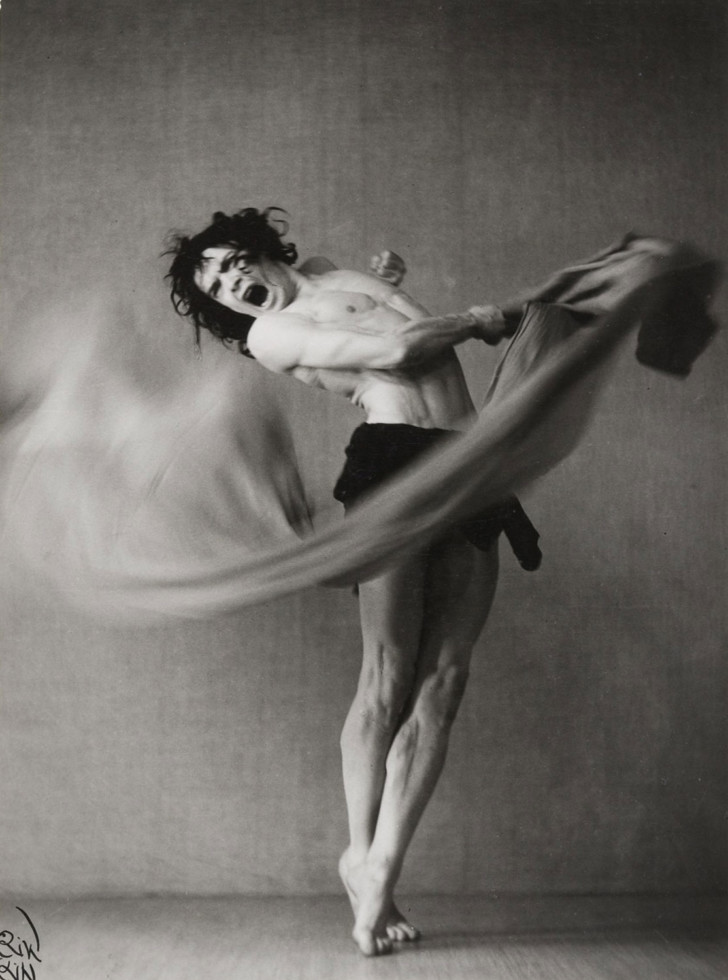

Anna Riwkin, [Dancer Alexander von Swaine], 1936 © Anna Riwkin/Moderna Museet

Dance photography – Anna Riwkin’s portrait of Alexander von Swaine

Finding models was, thus, never a problem for Anna Riwkin. She had an extensive circle of acquaintances herself and she was driven by a constant curiosity. She was to photograph many dancers in action, since it was precisely in her feeling for movement that she was so skilful.

Anna Riwkin started her ballet training in the 1920s with the famous Russian teacher Vera Alexandrowa. She also danced in the provincial parks that offered entertainment and was referred to in one local newspaper (Bollnäs Tidning) as “the little bare-footed dancer with an irresistible charm”. But after three years as a dancer she changed direction, opening her own photographic studio in 1928-29, specializing in photographing ballet and in portrait photography. She rapidly became the leading ballet photographer in Sweden and even established a reputation abroad.

In 1931 Anna Riwkin travelled to Berlin to study ballet photography and she became a pupil with Robertson. In 1932 a book entitled Svensk danskonst (The Swedish Art of Dance) was published. The book was illustrated with Anna Riwkin’s photographs. It was not until 1960 that the next dance book was published, Balettskolan (Ballet School). The famous Swedish choreographer Birgit Cullberg was one of the authors. In 1932 Riwkin took part in an international photographic exhibition, La danse et le mouvement, shown in Paris. For a short period she was also employed at the Royal Stockholm Opera.

Anna Riwkin’s meeting with the German dancer and choreographer Freiherr Alexander von Swaine took place in Stockholm. This was not von Swaine’s first visit to Stockholm but it was his first meeting with Riwkin. And at this meeting of two artists, the photographer captured the dancer’s originality and dramatic sense as well as his skilful technique. In the year that this photograph was taken, Hitler and the Nazis were in power in Germany. Alexander von Swaine was 31 years old and at the peak of his career. He was generally regarded as one of the era’s finest German dancers. Alexander von Swaine was also highly controversial. He had revolted against classical ballet and he was openly homosexual; something that was, of course, forbidden in Nazi Germany.

Alexander von Swaine, with his dance partner Alice Uhlen, made a guest appearance at the Academy of Music in Stockholm in 1936. On previous visits to Stockholm he had become enormously popular. His performances were especially valued for his highly individual and surprising presentation. The audience went completely wild and their thunderous applause was accompanied by stamping on the floor.

When he was young, Alexander von Swaine dreamed of being an actor but, as he grew up, he became increasingly fascinated by dance. He maintained his feeling for drama. He trained for eight years at the Russian ballet school in Berlin whereupon he found that career choices were very limited. In reality there were only three ways that he could go. He could dance at the opera, dance in variety or produce his own performances. He was not the slightest bit interested in variety and after dancing for a couple of years with the opera ballet in Berlin he chose to go his own way, touring as a solo dancer with his own productions. That he did not wish to be associated with variety depended on the fact that he did not consider it as being art but merely entertainment. Instead he performed his own compositions and he frequently found the inspiration for a performance on one of his lengthy walks in the mountains.

In the photograph the dancer is portrayed in the middle of the picture and is mainly lit slightly from in front on the left. The room is cold and empty, the dancer dressed only in a loin-cloth and holding a long piece of cloth. Alexander von Swaine is posing with his feet crossed at the ankles, the left foot in front of the right one and with his upper body stretched backwards like a bow. His left hand is folded into a tight fist by his chest while his right arm is moving the long piece of cloth in front of him. His dark, unruly hair falls across his face and his mouth is wide open, perhaps screaming. The photograph is arranged, taken in Riwkin’s studio but it is not a traditional portrait of a professional dancer. Instead of the usual elegant, gracious and enchanting movements, in her portrait Anna Riwkin has captured Alexander von Swaine’s force, intensity and passion. The dancer is in full control of events which is very evident in the frozen movements of his body; by the fact that von Swaine, unlike the cloth that he is holding, is shown in sharp focus.

The study is from a dance number entitled De Profundis (Latin for “out of the deep”). Alexander von Swaine was inspired to create this work by watching his housekeeper skinning an eel and it was evidently not unusual for von Swaine to find his inspiration in everyday events like this. His movement in the picture is like that of a matador who, at the very last minute, avoids being butted by the attacking bull.The long piece of cloth is equivalent to the matador’s cape. The blurred effect of the piece of cloth emphasizes the sense of powerful motion and it is easy to imagine the bull passing the dancer. Even the beholder is given a sense of being the bull that is being taunted by the bullfighter.

Alexander von Swaine’s bodily pose creates obvious associations with a drawn bow and in this sense the cloth is like an arrow that has just been released. There are two sonic elements in the picture: the rustling sound of the cloth and the forceful scream of the dancer.

Anna Riwkin has captured Alexander von Swaine’s power, control and artistic weight in an intimate manner. The blurred focus of the picture, something that was considered unforgivable in the 1930s, is central to the sense of importance of the photograph as well as emphasizing the movement. Riwkin has also succeeded in capturing the exact moment in a rhythmic progression that illustrates the emotionality of the dancer. With her own work of art she has portrayed the creative art of the dancer.

The portrait of Alexander von Swaine could not be published at the time (1936) because this form of blurred movement did not accord with contemporary ideas about pictures. But Riwkin frequently emphasized that, for her, the important thing was that the attraction was to be found in the subject itself and that the technical aspects were not of primary importance. Anna Riwkin thought that the artistic element should be fundamental and that technical matters were subsidiary. Perhaps this was a way of defending herself since her colleagues did not consider her to be a technically expert photographer.

What happened to Alexander von Swaine? He fled from the Nazis and was interred by the British in Burma.After World War II he worked for a couple of years in India and then returned to Germany. From 1960 onwards he taught classical and modern dance at the Bellas Artes College in Mexico City. Alexander von Swaine died in 1990 in Cuernavaca in Mexico.

Anna Riwkin’s dance photography was very unprofitable and her expenses were greater than her income from it. This may have been one of the reasons why she began to interest herself in other genres. But she continued to photograph dance for almost the whole of her professional life. Her temperament caused her constantly to look for new challenges and travelling had always attracted her. So that it seems natural that she later combined dance photography and portraiture with reportage photography for her numerous books.