Anna Riwkin, No title. From the series Gipsy Road 1954-55. Stina Taikon cooking for her children in her caravan, 1954 © Anna Riwkin/Moderna Museet

Anna Riwkin’s Photographs

The portraits represented famous Swedish authors, artists, choreographers and composers. Although it is more than thirty years since Anna Riwkin died, interest in her photographs is at least as great today as it was during her lifetime. This is something that can be measured by the large number of scholars, publishers and private individuals who ask for her photographs. Moderna Museet owns her collection of negatives, contact copies and about five thousand photographs. Furthermore, the museum’s photo library holds her books, while the History of Photography archives contain a small amount of correspondence and a certain number of documents about her life and work. The letters that were exchanged between Anna and her sister Eugénie, on the other hand, are preserved in the Special Collections Department & University Archives of the State University of New York at Stony Brook, in the United States. There is also some pertinent material in the collections of the Jewish Museum in Stockholm.

In order to create a museum of photography, the Swedish state obtained through purchase or donation a number of photographic collections at the beginning of the 1970s. These included, in addition to Helmut Gernsheim’s duplicate collection and Professor Bäckström ‘s historical collections – both acquired in the middle of the 1960s – such collections as those of Svenska Fotografernas Förbund (Swedish Photographers’ Association)), Fotografiska Föreningen (Photographic Society of Stockholm), Svenska Turisttrafikförbundet (Swedish Tourist Traffic Association), Svenska Turistföreningen (Swedish Tourist Club) and Pressfotografernas klubb (Press Photographers’ Club), as well as the donation from Tio Fotografer (Studio Ten Photographers) and the collections of various Swedish photographers compiled by Fotografiska Museets Vänner (Friends of the Photographic Museum).

The largest individual collection nevertheless came from the estate of Anna Riwkin. At the end of the 1960s (she died in 1970), the photographer had bequeathed her collection to a future museum of photography on condition that her assistant and longtime colleague, Erik Brandius, would still attend to requests for her pictures. The photo copyright, according to the will, was temporarily transferred to Brandius. The photographs were to be taken from the archive as long as Brandius was still alive or fit to take on the work. It was a task that he carried out in a positive and energetic fashion for more than thirty years, in spite of increasing ill health and gradually reduced physical strength. Brandius had begun working as an assistant to Anna Riwkin in the late 1940s and remained with her up to her death in 1970.

He died in the summer of 2002 and the photo copyright then fell entirely to the museum. Brandius had also periodically been a great help to the Museum of Photography and the Moderna Museet in cataloguing the extensive collection of gelatin silver photographs, negatives and contact prints.

Brandius, who was an unusually warm and friendly person, made a major contribution to the preservation of Anna Riwkin’s collection, as well as to the memory of her personality and artistry. In spite of Riwkin’s will, it was nevertheless by Lars Erik Brandius’s personal efforts that the material was actually transferred to the nation and did not disappear along the way. This is something we have every reason to be grateful for, since many photographic collections were still being destroyed at the beginning of the 1970s through lack of interest or knowledge on the part of surviving friends or family. This happened in spite of the express wishes of many skilled photographers that a national or municipal institution should take care of their life work after their death.

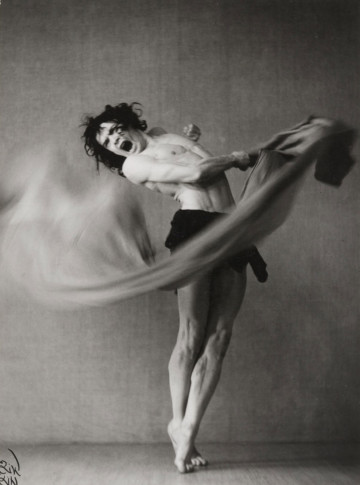

During the 1930s, Anna Riwkin developed into an expert photojournalist and was well prepared when illustrated magazines such as Se and Vi made their entry into every household. She worked alternately as portrait and stage photographer and was particularly interested in ballet and dance. Ballet was an art form which she herself had practised and which she therefore grew skilled at representing in photographic images. As a photographer, Anna Riwkin became most famous for her children’s books, but also for her collaboration with various Swedish authors, particularly Ivar Lo-Johansson in his reportage on Swedish Gypsies or Roma, as well as the journalist Elly Jannes in her books on the Sami and Astrid Lindgren in her children’s books. Anna eventually took on the whole world as her field of operations and became internationally famous. Information about Anna Riwkin’s earlier years is rather limited, however, and varies according to the source.

In going through Anna Riwkin’s photographs for the exhibition it was therefore important to look for information about her early life and to discover what it was that moulded her into the creator of pictures she became. It was also necessary to try and discover the various perspectives defining Anna Riwkin’s life as a photographer, as well as to study and clarify her family relations and to describe her domestic environment.

Anna Riwkin had psychological recollections from the very earliest years of her life; Russian anti-Semitism existed as something self-evident in her life, one was brought up with it, one was a Russian Jew, not a Russian.

It was also important to study how the regulations were formulated for aliens residing in Sweden previous to, and current with, Anna’s arrival in the country. How did the family relate to Swedish society and its cultural life on their arrival in Stockholm? Why did the Riwkin family settle in Stockholm? Questions such as these arose in attempts to capture Anna Riwkin, the photographer and the individual. It is at the same time necessary to emphasize that Riwkin was a Swedish photographer with a prominent position in the Swedish photographic fraternity. She shared her colleagues’ values even if she belonged to a different faith to most of them. Anna Riwkin was a vivacious person, but not necessarily therefore a maverick in her day. She was respected by both colleagues and contemporaries and also had a wide circle of friends among the people who participated in Swedish cultural life.

Leif Wigh