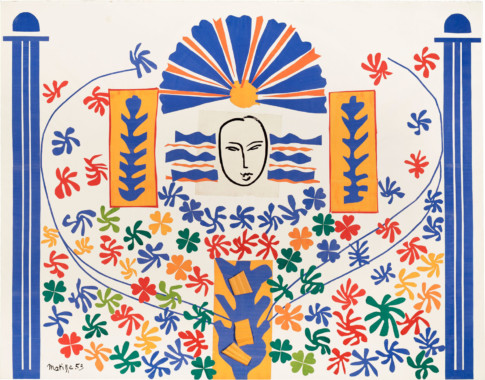

Siri Derkert, Mauresque I, 1914 © Siri Derkert/BUS 2011

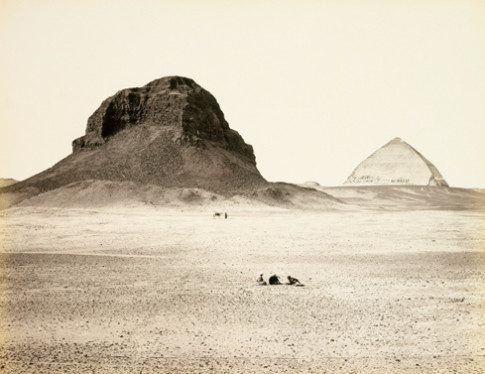

Travelers in time and space

Returning to Paris in the 1910s, Aguéli found himself in the midst of modernism’s great breakthrough. His writings are considered some of the most unique interpretations of Cubism. Relying on his background in Sufism, he compared the Cubists’ analysis of the unity of space and time to a Dervish whose whirling dance seems to open space toward a greater all. Aguéli’s life was a journey laced with challenges: defending European representational art to his Muslim brothers and at the same time earning the understanding of his colleagues in Paris for the greatness of the tradition of Islamic thought.

North Africa also attracted a few female artists from Sweden during the years around the turn of the last century. Siri Derkert, Lisa Bergstrand, and Ninnan Santesson traveled to Algeria in 1914 just before the outbreak of the First World War. The idea of three women traveling alone without male escorts was considered extremely daring. At the same time, their foreignness allowed them to move relatively freely within the alien culture—perhaps more freely than they could in Sweden at the time. During her journey through Spain in the late teens, the artist Vera Nilsson wrote:

But there are still quite a few vexations for a woman traveling here. /—/Many of the women are jealous of the foreigner who won’t be confined behind iron bars…who walks the streets alone and does as she pleases. I have even been able to take greater liberties than at home, as no one says other than that everyone does so in her country.