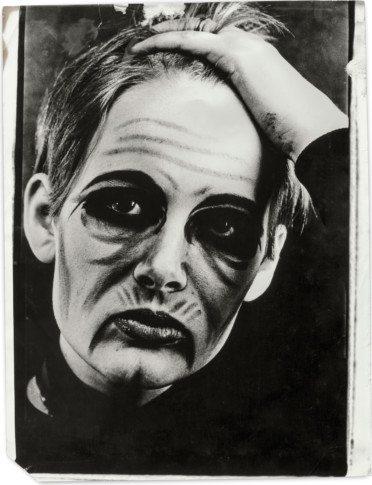

Produktionsbild från inspelningen av filmen Hallo Baby (Svenska Filminstitutet), 1976 Photo: Walter Hirsch/Filminstitutets bildarkiv

Marie-Louise Ekman’s films

Film Programme

2–3 September 2017 Film festival

9–10 September 2017 Målarskolan [The Art School]

16 September 2017 Nu är pappa trött igen [Dad is Tired Again]

17 September 2017 Hallo Baby

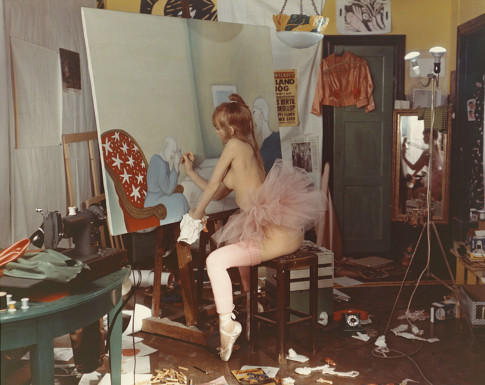

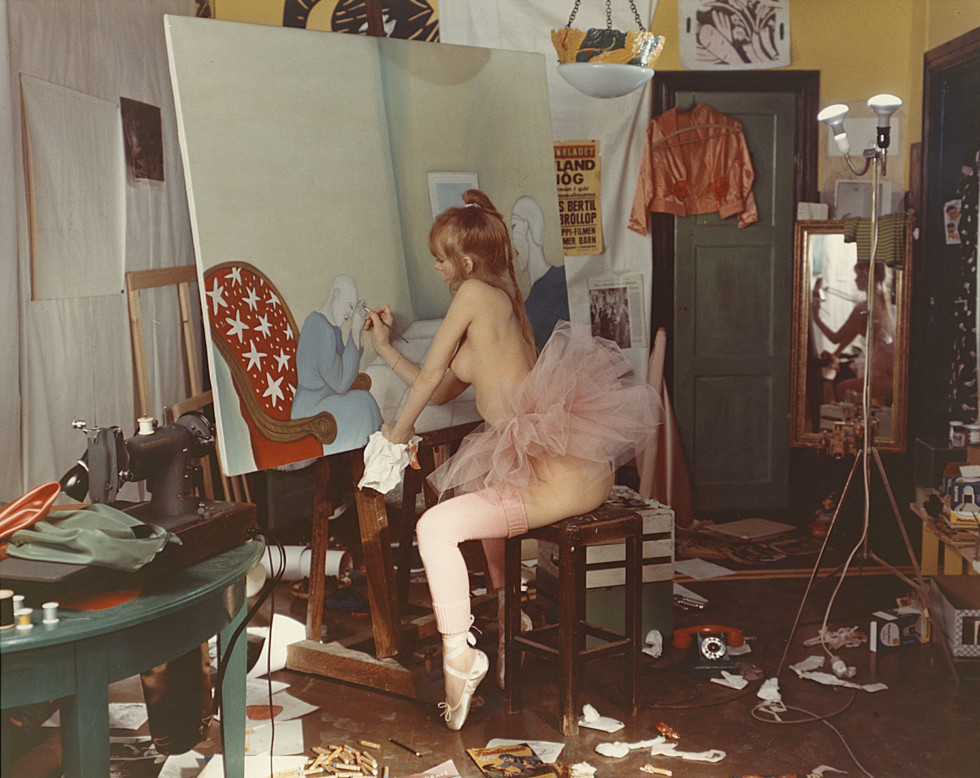

Hallo Baby (Hallo Baby), 1976

Hallo Baby was Marie-Louise Ekman’s first and perhaps most famous film, written by Ekman herself and directed by her then husband Johan Bergenstråhle. The story revolves around the adolescence of a young girl and is often described as partly autobiographical. Against brightly-coloured backdrops signed Carl-Johan De Geer, Ekman portrays a childhood marked by perpetual conflict between the parents and the father’s decadent life in Stockholm’s theatre world. When the girl grows up and leaves her childhood home she makes her way into the art circles of the capital. The girl, now a young woman and played by Ekman, moves in and out of different spaces and relationships; even though constantly on the move, she seems to have no clear direction. At times she is tossed along the storyline like a doll with only the barest glimmer of facial expression. And yet becoming a woman is ultimately shown to be a productive process: Ekman’s Baby puts on and takes off both clothes and identities and finds strength in traditionally feminine forms of expression.

Mother, Father, Child (Mamma, pappa, barn) 1977

The half-hour-long Mother, Father, Child, Marie-Louise Ekman’s debut as a film director, is aimed primarily at a younger audience. The cultural life available to children as envisaged by previous generations would be increasingly criticised during the 1960s and 1970s. Many people felt that what children encountered in that culture was an idealised image of the world which meant they were neither exposed to nor allowed to have “awkward” feelings such as rage, hate and grief. Ekman wanted to change that. Mother, Father, Child is played out at the eye-level of a girl struggling with the restricted role allotted to her by the adult world. To the girl’s eyes the world of her parents appears alien and bizzare – a feeling that is intensified by the peculiar set design. No one else can see things the way she does, and no one can see who she really is. Employing black humour while at times tackling weighty subjects, Ekman expands the notion of what it means to be a child. Lively as the girl’s imagination may be, the depiction of the emotional life of the child is just as realistic in a film in which everything is permitted.

The Elephant Walk (Barnförbjudet), 1979

The Elephant Walk follows up many of the themes Marie-Louise Ekman introduced in Mother, Father, Child (1977). Ekman was keen to get away from a distorted Romantic view of children’s emotional lives by widening the range of feelings her young characters experience as part of contemporary culture. In this film we encounter a young girl dreaming of her birthday party – a huge celebration that involves both her family and the children and staff from her day care centre. The girl is awoken by her parent’s quarrelling and her mother then leaving their flat in fury. The dazzling colours of Carl Johan De Geer’s set allow the design to play with scale and form and to be sensitive to the child’s highly imaginative point of view, both asleep and awake. In the midst of life at its most enchanted Ekman has the girl experience the disturbing and painful aspects of the adult world she does not as yet really understand.

Still Life (Stilleben), 1985

Ekman’s work on theatricality, spatiality and role-play all feature in this singular full-length film. An ensemble of actors that includes Johannes Brost, Rolf Skoglund and Örjan Ramberg portray a family and their friends who spend a day on a sunny terrace outside a magnificent villa in the country. With powdered faces and dressed in historical costumes they play out an absurd and incoherent chamber play in the classical 18th-century style. A girl hovers on the periphery of the scenes – the daughter of the family, who in contrast to the exaggerated and affected image created by the other family members appears to be the only sensible person present. Despite the lack of any clear plot the fragmentary dialogue manages to capture a distinct tone and sense of mood. With a script strewn with cultural references and which plays games with gender, sexuality and identity, Ekman pushes many of her classical themes to their extreme. A dramatic turn occurs at the end of the film that opens up new worlds.

The Tale of the Little Girl and the Big Love (Sagan om den lilla flickan och den stora kärleken), 1986

The absurd and the surreal are recurrent stylistic features of Marie-Louise Ekman’s cinematic oeuvre with affected and artificial dialogue being interspersed with lofty music and staged against unreal and dramatic set designs. Her short film The Tale of the Little Girl and the Big Love reflects these trends. In many ways the work is a consideration of the modern and normative ideal of love. The little girl, played by Annika Nuora, is seated in a darkened restaurant waiting for “her prince”. Instead of meeting the right man the girl finds herself being hurled out into life, and all the expectations she had of love are turned upside down. Scenes from her life are juxtaposed with humorous illustrations inspired by paintings by Ekman that are linked in some way with the theme of the film. The action is accompanied by an at times ironical female narrative voice that follows the gradual transformation of the girl from a naif to a sceptic – even though the dream of the prince is never entirely erased.

The Art School (Målarskolan), 1990

Marie-Louise Ekman was Professor of Painting at the Royal Institute of Art from 1984 to 1991. During this period she also produced a television series in ten parts dealing with life at an art school. All the roles – including the female ones – were played by men, and Ekman employed several of the actors who had worked in her previous films, including Johannes Brost, Rolf Skoglund and Örjan Ramberg. Ekman has described the device of dissolving or shifting gender identities as a means to make the approach to the problems tackled in her films more human. This humorous series is nevertheless almost inhumanly distorted and the twenty-minute episodes can at times seem incomprehensible. Each episode is introduced by stories from the lives of students and staff at the school and ends with a song to music composed by Benny Andersson. “Why the hell would you ever want to be an artist unless you are doing what you want?” Ekman wonders in an interview. The Art School demonstrates a creative and many-sided artistry that explores social conventions and group dynamics with great integrity.

The Secret Friend (Den hemliga vännen), 1990

A couple in late middle age are living in a beautifully designed loft. The woman, played by Margareta Krook, alternates between fury and irritation. She spews spiteful remarks over her sick husband, who is played by Ernst-Hugo Järegård. The man remains silent and simply submits. He only gives vent to his feelings in belligerent monologues to the camera and in conversations with his friend, played by Gösta Ekman. In order to portray his wife’s behaviour the husband stages various kinds of role-play. The two friends dress up in the wife’s clothes and alternate between playing the woman and the man, the oppressor and the oppressed. Without ever allowing the camera to leave the apartment, Marie-Louise Ekman slowly splices together various stories about disintegration. The decay of the sick body and the failing relationship are depicted side by side with the disintegration of identity, gender roles, sexuality, and eventually even – when a fourth character is introduced to the story – the dissolution of professional identity and status. With equal measures of humour and seriousness, Marie-Louise Ekman reveals that not everything is what it seems to be. The real identity of the “secret friend” is not disclosed until the end of the film.

Dad is Tired Again (Nu är pappa trött igen), 1996

Mr Khopp, played by Gösta Ekman, is hospitalised owing to his extremely inebriated state. He has to share a room with a man who has difficulty controlling his movements and his speech. Khopp appears not to notice his neighbour’s difficulties, but just keeps talking in the form of long, one-sided tirades. Touching considerateness is allied to sheer invective and slowly the foundations are laid for an odd and dysfunctional friendship. When the stay in hospital is over Khopp relapses into alcohol abuse and is thrown out of the house by his wife. The daughter of his previous marriage, who is played by Rebecka Hemse, appears to be the only person who has not grown tired of her father. With a large dose of humour Dad is Tired Again tackles weighty subjects like alcoholism and power relations. The film depicts a problematic but devoted connection between father and daughter; despite Khopp’s evident narcissism he is portrayed with both tenderness and love.

Bildupphovsrätt 2017

The Dramatic Asylum (Den dramatiska asylen), 2013

Marie-Louise Ekman served as artistic and managing director of the Royal Dramatic Theatre from 2009 to 2014. In the autumn of 2013 just before her final year in the post she recorded a series of 50 episodes about her time at the institution. The series was directed and filmed by Ekman herself using her smartphone camera and depicts the various dynamics operating between the employees in the theatre’s different departments. Ekman manages to interweave humour and tragedy in a series that reveals the hierarchies, visible and invisible, that characterise even the loftiest workplace. Among the characters in the episodes we encounter a wealth of variations on Ekman herself, the heavily made-up artistic director in her characteristic spectacles, played by actors such as Marie Göranzon and Stina Ekblad. “I think I have come to a perfectly ordinary place of work,” Ekman writes. “But these are my own subterranean tunnels. / It turns out./ During the course of the journey./ A jungle./A zoo./ A hospital./ A workplace story in various parts.”