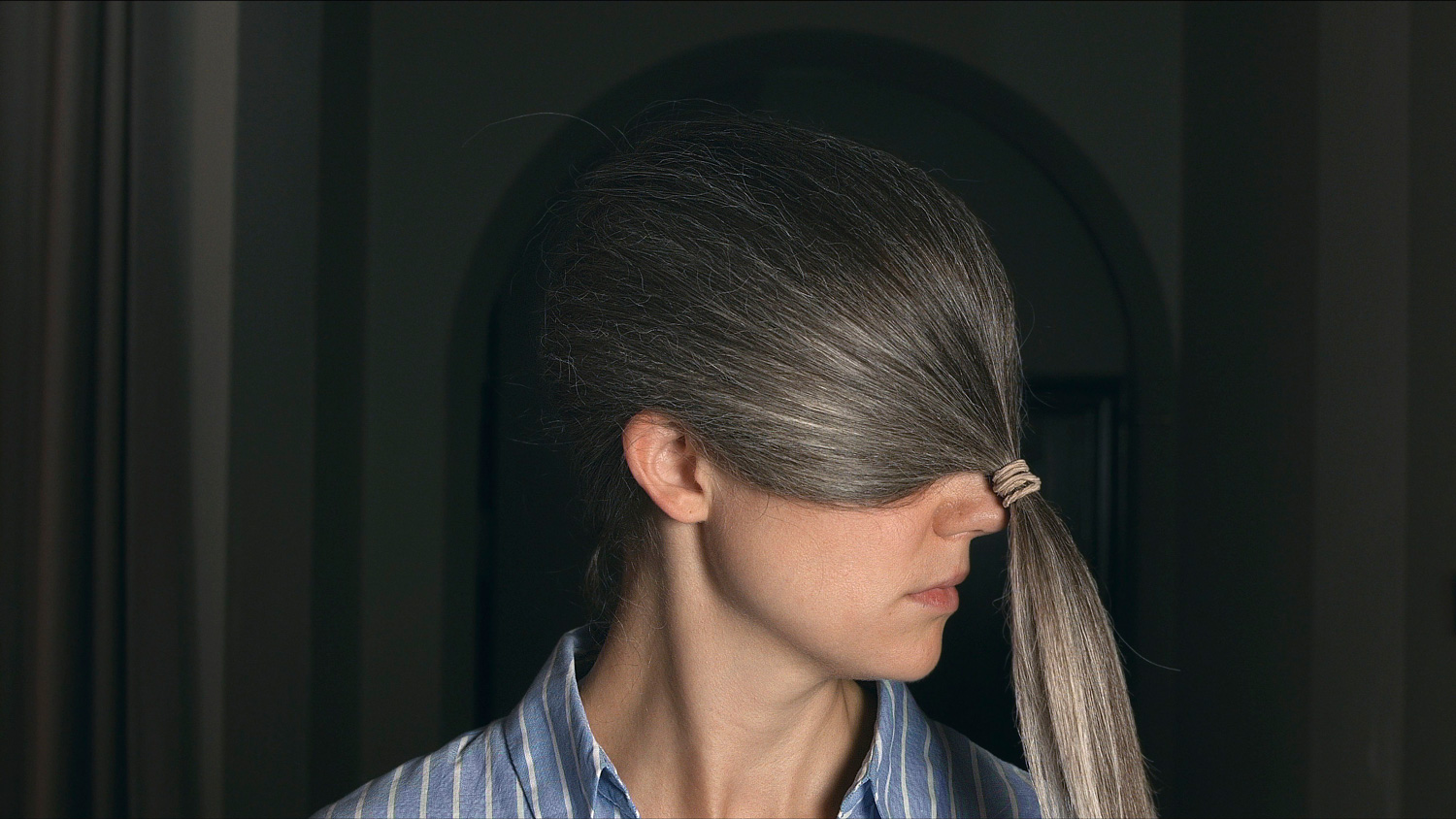

Ingela Ihrman, Jättebjörnlokan [The Giant Hogweed], 2016 Image from work in the studio. Courtesy the artist © Ingela Ihrman

Participating artists

Meriç Algün

Born 1983 in Istanbul

The central Galata neighbourhood in Istanbul was a rural fig tree orchard in 100 AD. During a stay there, Meriç Algün looked for the symbolic remnants of the lost plantation. As in many other works, she approached her subject in an investigative manner. She walked around methodically photographing the fig trees that today grow between the cobblestones, in courtyards and on parking lots in the area. Moving around in the area as a woman provoked a lot of reactions, particularly among men. She wrote down what she saw during her rambles in a notebook and reflected on the experience of being watched.

At the same time Meriç Algün conducted research on the common fig, which proved to have many connections to what she experienced on her walks. The fig is a “false fruit” that is fertilised by a certain type of wasp. The flowers inside the fig are unisexual and in modern plantations the male and female trees are kept apart for the sake of control and to increase the size of the crop. In cultural history, fig leaves have been used to cover the sexual organs of painted and sculpted bodies and the fruit itself is considered to be sensual with erotic undertones.

The fig’s different associations and the artist’s impressions from the Galata area form the basis of the installation ”The Orchard of Resistance”, which deals with public space, lost paradise and patriarchal society.

Muhammad Ali

Born 1982 in Al-Malikiyah

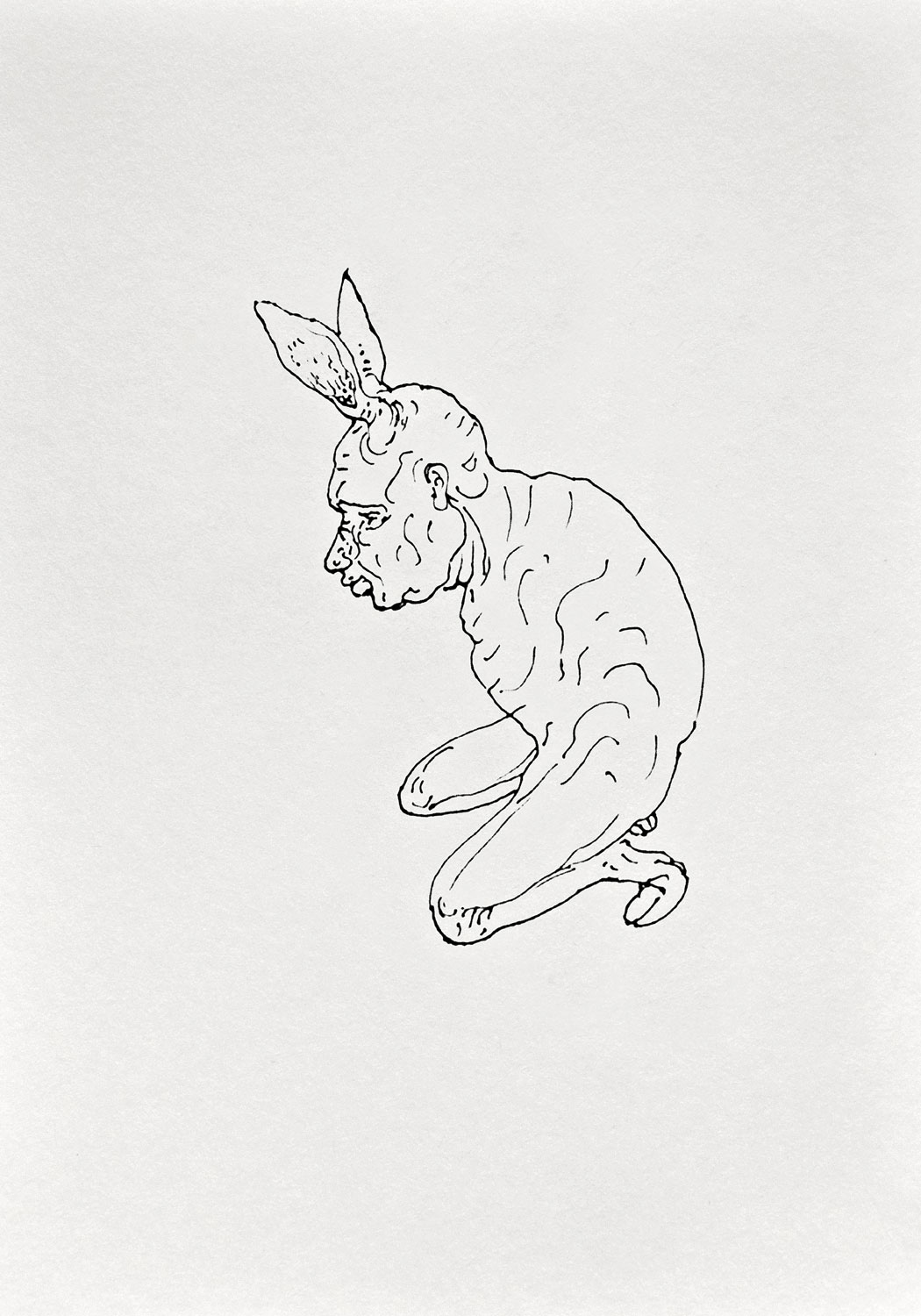

The observations that Muhammad Ali made in Damascus and captured with ink on paper in ”366 Days of 2012” convey a strange tale of life in the city. The figures are deformed human/animal hybrids. When imminent danger becomes part of everyday life, mental metamorphoses in the population ensue. To Muhammad Ali, the role of art in articulating such processes is crucial. The series is part of the extensive work ”Diary of a Roamer”.

In another part, the video work ”Neither Human, Nor Stone”, black blocks fall, like stone rectangles in front of a firing squad. The background for the work is that Ali witnessed people literally collapsing in the streets. The numbness or indifference in the face of anger, sadness and vulnerability were shared by the passers-by – they saw the bodies fall and walked on, completely exhausted themselves. In the series ”Endless Days”, one of the men in the drawing wears an overall with sewn-up sleeves; his feet are shod in wire cages. “EVERYTHING IS SUPER” is written across his chest.

Human material and stone that collapse, hope that dies – realities of war. In the spring of 2016, after five years of war, Muhammad Ali fled his homeland across the Mediterranean and onwards to Sweden.

Emanuel Almborg

Born 1981 in Solna

Emanuel Almborg investigates historical and new educational methods that develop mindfulness and learning on children’s terms. The video piece ”Talking Hands” (2016) is about the radical Zagorsk school for deaf-blind pupils outside Moscow where the students learn a kind of hand language that takes them out of their isolation. The school was established by the philosopher Evald Ilyenkov in the 1960s, at odds with the prevailing state ideology. A former student is interviewed about the school’s history. The sensitive editing ties the artist’s intensely listening eyes together with the man’s talking hand movements and the school’s archival images of children exploring their surroundings using the sensitivity of their skin.

Should pedagogy and children’s thinking be redefined in times when new technology is available? The question is highly relevant and the subject of a new version of the work ”Learning Matter”. In 2018, Emanuel Almborg collaborated with his mother Agneta Almborg, a special needs teacher specialising in language, on a workshop with children from the school in Tensta outside Stockholm where she works. The analogue black-and-white photographs were taken by Agneta Almborg and show how the children gather knowledge and train their concentration abilities using digital tools and tactile materials. The first version of the work was created with British children in London in 2017.

Ragna Bley

Born 1986 in Uppsala

The oils flow as if they were watercolours in Ragna Bley’s paintings that measure more than three metres in height. By using unprimed sailcloth, she gives the colours the potential to bleed across the canvas. The diluted paint finds its own expression in the encounter with the surrounding colours and canvas, as though it were a sentient, autonomous creature. The colours alternate between artificial and organic, physical. The super-human formats mean that we can enter them with our gaze, like landscapes or unique microcosms for us to explore.

Abstract at first glance, these paintings give the impression on closer inspection of having more specific meanings. Bley’s interest in the natural sciences, science fiction and bio-politics is apparent in the poetic titles of her works, such as ”Armchair Climate”, ”Friday Carcass” and ”Plastic Sluice”. These titles inform our viewing and open new associative paths between the colour fields that flow in and out of one another on the partially unpainted canvases.

Alfred Boman

Born 1981 in Luleå

Clear, luminous colours that drop and run or are tamed into demarcated, stencil-like fields. Colours that lie almost hidden under other colours or stand out similar to shards of a mosaic. Alfred Boman’s abstract paintings are reminiscent of the stained-glass windows of a church or cathedral. Some of them are mounted in welded stands that are placed on the floor like folding screens. One part of the work is a painting, the other a kind of metal drawing.

At times the atmosphere in Alfred Boman’s work is sacral, although the paintings tell neither biblical nor profane stories. As the artist himself says, “I don’t work narratively”, and yet, both figurative elements and esoteric symbols emerge from the layers of colour. Other paintings, such as the diptych ”Snorkeln och Vitor” (2016), are black-and-white and austere, almost sculptural. They bring to mind so-called rayographs, that is, photographic images that are created by putting objects directly on light-sensitive paper. Regardless of expression, his artworks seem to exist in a dimension beyond words.

Kalle Brolin

Born 1968 in Ängelholm

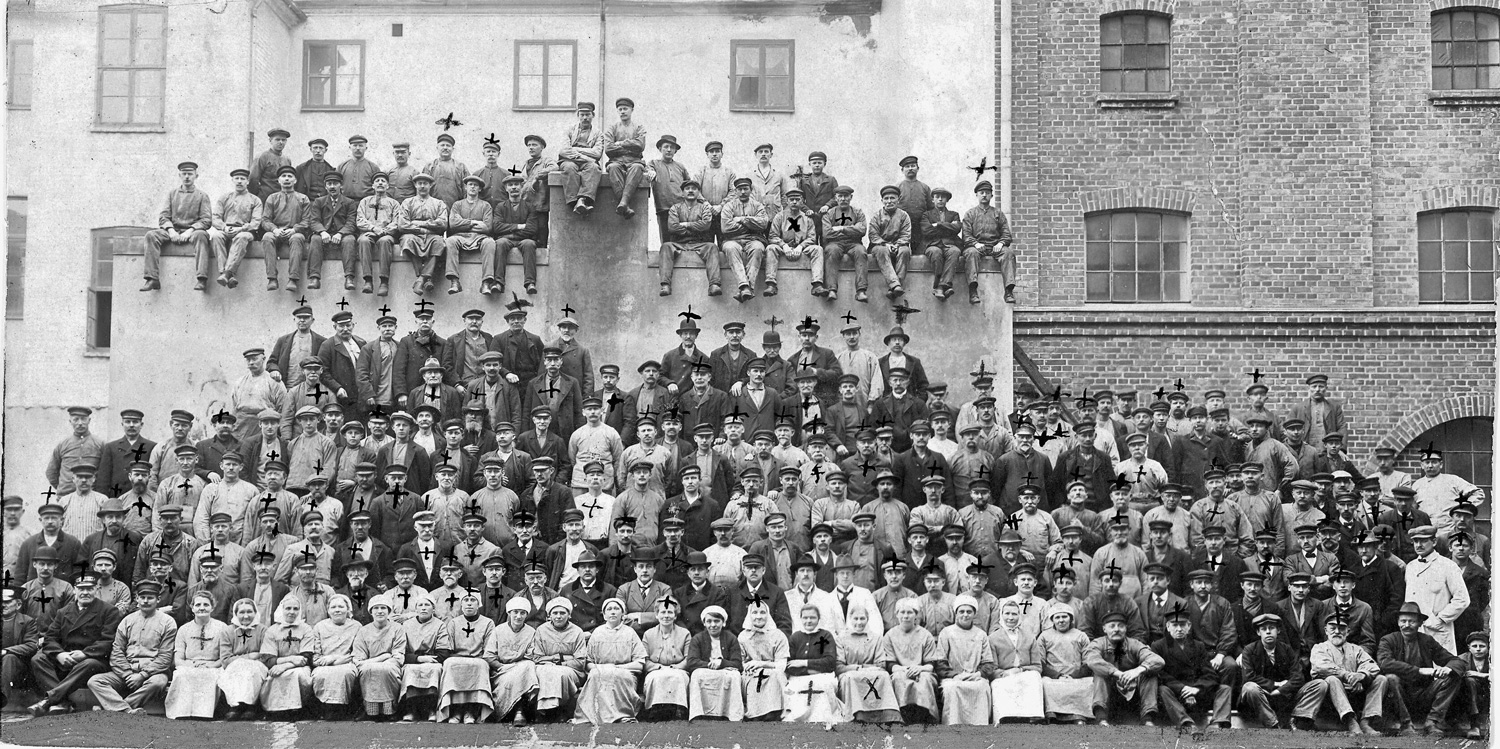

Skåne is the only county in Sweden that has been involved in the coal mining industry and its soil is perfectly suited to the cultivation of sugar beet. The men toiled in the hazardous coal dust and the women bowed their bodies with hard work in the furrows of the sugar beet fields or did shifts at the sugar factory.

In the video piece ”Jag är Skåne” (2017) (I Am Scania), Kalle Brolin reflects on the history of work in the landscape of his home county and specifically on how “coal was fuel for the machinery as sugar was fuel for the workers”. He investigates the coal and sugar industries to show how the factories worked together in the initial stages of industrialism and the emerging welfare state and how people were used, sometimes against their better judgment, to promote industrial profitability.

Stills and film clips are culled from archives and have been deposited on small digital tablets that Kalle Brolin has placed on a conveyor belt to illustrate the connection between industrial labour and his own film work. From the collected material, a parallel narrative also emerges about the Vipeholm experiments in Lund between 1947 and 1955, where “feebleminded” patients were systematically fed caramel and chocolate between meals. The experiment was financed by the sugar industry and led to severe tooth decay in the patients, but also to new insights about dental health in modern Sweden.

Fanny Carinasdotter, Anja Örn, Tomas Örn,

Fanny Carinasdotter, born 1978 in Avesta, living in Umeå.

Anja Örn, born 1972 in Stockholm, living in Luleå.

Tomas Örn, born 1976 in Stockholm, living in Luleå.

”Att använda landskap” (2016–17) (Using Landscapes) is the title of the joint video piece by the trio Fanny Carinasdotter, Anja Örn and Tomas Örn. All three artists have long been active in the north of Sweden. The work shows stills of ravaged virgin forest, destroyed homes, as well as a broken landscape around the country’s largest copper strip mine Aitik, south of Gällivare in Norrbotten County. Aitik is a Sami word that means storehouse, but the wealth of copper is rapidly being depleted by the mining industry.

In a double projection, the artist trio alternates stills with voices from inhabitants of the area and facts about the mining industry and its profitability. The local population is worried about their homes and about how the expansion of the industry is destroying the cultural landscape. At the same time, the mining operation has meant that many people have found employment. A third video shows the relentless passage of time, here forced by human hand – the industrial era.

At the current rate of mining, the deposits are calculated to last until 2029. What is left behind after that is a gigantic hole in the bedrock and a ravaged landscape.

Kah Bee Chow

Born 1980 in Penang

Like buildings in a landscape or notes in a musical score, a panoply of sculptural objects spread across the floor in Kah Bee Chow’s installation 海龜. Together, the two Chinese characters of the title form the word for sea turtle. In Chinese, this word was originally represented by a pictogram that clearly showed the creature’s back, unlike the way it is written today. Like the separate lines in a Chinese character, the repeated formal elements in the work combine into a larger narrative.

Traces of the turtle’s shape and meaning are repeated throughout the work. The aluminium shields, for instance, refer to the Roman legions who used a tortoise formation as an impenetrable defence against projectiles.

The sea turtle has a special significance to the inhabitants of the Malaysian island of Penang where Kah Bee Chow was raised. The island’s irregular coastline resembles the contour of a sea turtle, which is traditionally believed to bring good fortune. But feng shui experts are now concerned that human intervention with the coast is putting the population’s welfare at stake. Often, mankind seems to need a shield against itself.

Rebecca Digby

Born 1987 in Hammersmith

Rebecca Digby’s video installation ”Impulsion II” confronts us with a machine that produces codependency. We can follow an intricate design process on the bright, rectangular built-in LED screen. White, architectonic elements regroup at regular intervals to form new constellations. The ever-changing surfaces of the evenly-lit machine parts almost give the impression of a kinetic minimalist painting. In the clinical setting, however, fragments of human bodies suddenly protrude through various cavities. Disembodied fingers, limbs and heads interact with each other in the closed system. An arm pops up unexpectedly behind a screen, only to tug at a finger sticking out from a hole somewhere else. The machine perpetually generates new interactive possibilities between the severed body parts.

Man and machine exist here in a codependency, where the combination of muscular and mechanical power seems to have an infinite potential to engender relationships full of both tenderness and violence.

Sven X-et Erixson

Bron 1899 in Tumba

At the end of World War II, the so-called White Buses of the Swedish Red Cross arrived in Malmö transporting refugees from the concentration camps of Europe. Ernst Fischer, the director of Malmö Museum at the time, decided to open the museum’s doors to the refugees. Doctors, nurses and the museum staff worked side-by-side in receiving them.

“When in the end the museum’s illuminated entrance hall welcomed them and they walked up the stairs in radiant light and with the best art Sweden has to offer hanging on the walls, they stopped and pinched one another in the cheeks to make sure they were truly living creatures. Are we not dead and ascending the stairway to heaven?”

Sven X:et Erixson was taken with Fischer’s description of the event and painted the large-scale ”Flyktingar i Malmö museum” (Refugees in Malmö Museum) the same year, 1945. The skeletal shadowy figures are welcomed by nurses standing in a row on a grand red staircase like angels in white.

This is how the refugee crisis was handled then. What do we do today? Despite the fact that Sven X:et Erixson’s painting is more than seventy years old by now the work seems current, since it sheds light on a theme that many artists approach today.

Malin Franzén

Born 1982 in Stockholm

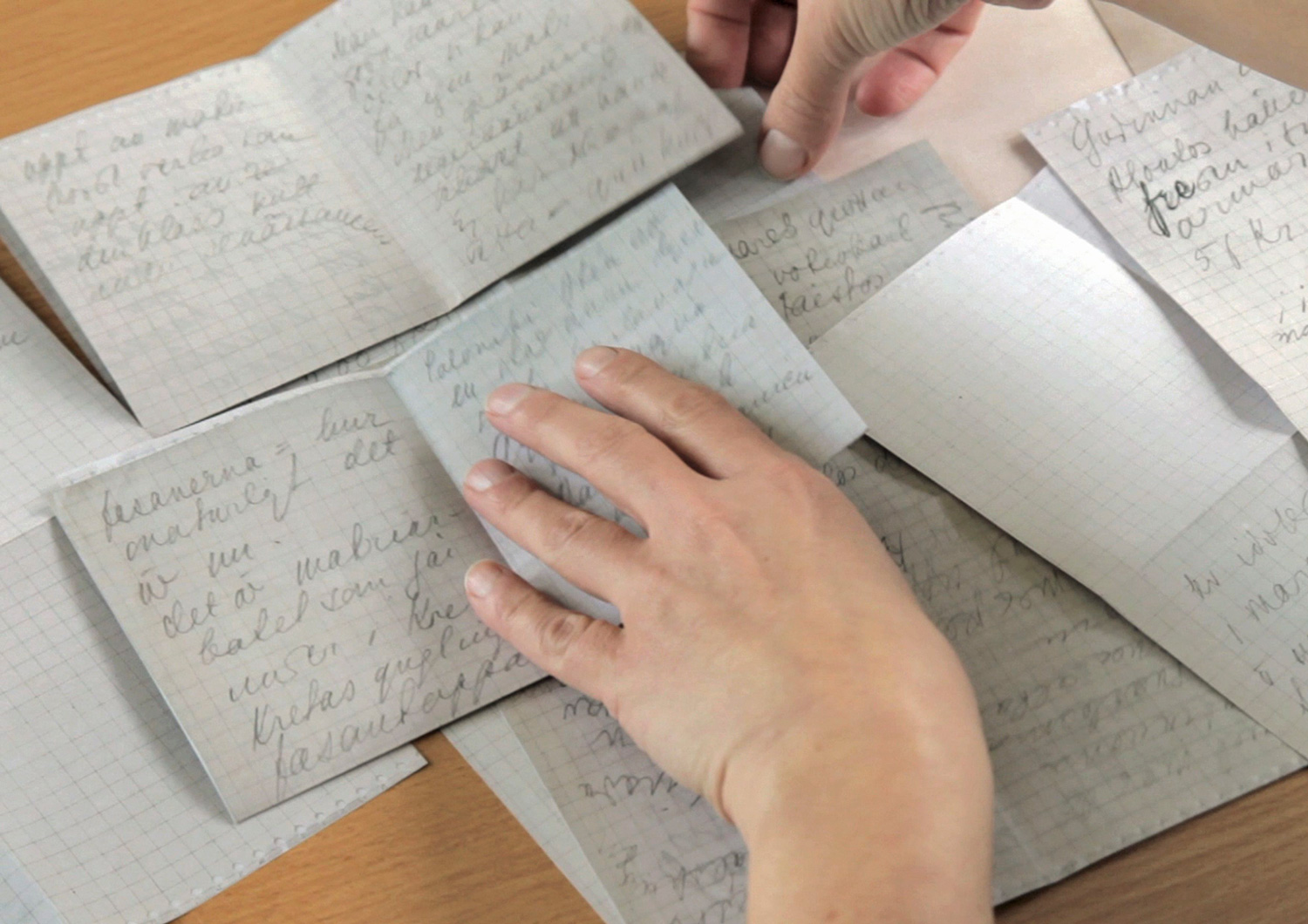

Like an archaeologist who studies the shards of a forgotten time, a scholar of the history of ideas in Malin Franzén’s video piece ”For Long We Live on the Ruins of the Past” tries to decipher a number of text fragments. The hastily written lines come from the feminist writer, thinker and peace activist Elin Wägner’s field trip to Crete in 1937. Wägner was looking for remnants of ancient matriarchies and the aim was to find a peaceful counterimage to the war-torn and patriarchal 1930s. She published her thoughts in the book ”Väckarklocka” (Alarm Clock) in 1941, and that’s where the title of this video piece comes from.

Malin Franzén is interested in interpretations and reinterpretations of history. In ”For Long We Live on the Ruins of the Past” this topic is subjected to a double exposure. Wägner interprets the traces of the former matriarchal culture, while Franzén lets a scholar interpret Wägner’s fragmentary and unedited thoughts. In addition to the video piece, Franzén has also created poems based on the scholar’s reading aloud of the text fragments. Every short pause makes for a new line, every longer break a new poem. In this way the shifts of both content and form that are part of every translation process are made visible.

Mark Frygell

Born 1985 in Umeå

Mysterious, closed faces. Twisted bodies pressed together in strange positions and with ambivalent relations. Dominance and submission, tenderness and brutality.

Mark Frygell’s paintings are colourful and his brushmarks powerful. The bodies have weight and integrity and are often portrayed against neutral backdrops. Certain details emerge as in an X-ray: a shoulder joint or a knee cap, a collar bone or a calf muscle. The paintings are filled with layer upon layer of references to comics, subcultures, advertising and, not least, art history. “I could imagine my art as a caricature of art history and our collective aesthetic memories”, says the artist himself.

As a springboard for the large paintings, Mark Frygell makes much smaller pen and ink drawings across the printed pages of different books. When the text in the book becomes just a backdrop to the black lines, it loses its original function and meaning and instead becomes part of the visual composition. A third element emerges, where image and text intersect.

Erik Mikael Gudrunsson

Born 1980 in Sundsvall

”Resa i Norrland” (Journey in Norrland) is the title of a photographic journey that Erik Mikael Gudrunsson undertook between the 12 May and the 10 October 2008 and which resulted in a photobook in 2013.

In the work, Gudrunsson follows the route laid out in Carl von Linné’s travel journal ”Iter Lapponicum” (A Tour in Lappland) and photographs the places that Linné visited in 1732. He does this in an attempt to assess to what extent the landscape has changed in what is almost three centuries that have passed since then. The purpose of Linné’s expedition was mainly to examine the natural resources of Norrland and answer questions about how the provinces could be exploited for economic gain.

The pre-industrial landscape, which for Linné was a waste of untapped potential, e.g. for forestry and cultivation, is nowadays highly exploited and marked by industrial business operations. Erik Mikael Gudrunsson’s work draws attention to both the extensive transformation of nature and the colonisation of traditional Sami regions that has occurred and is still ongoing.

Thomas Hämén

Born 1987 in Luleå

The polar bear has become a symbol of the climate crisis in our era of global warming. Thomas Hämén’s work ”Kalluk och Tatqiq” shows a live video stream of two polar bears at San Diego Zoo, held in captivity and closely monitored so that we can follow their every move. Computer-animated flies are moving around on the surface of the image. The screen’s red colour comes from the chemical element Europium, which, just like the polar ice, is a limited resource.

In the work ”Tyrian Red”, an LED screen has been lowered into an aquarium filled with mineral oil. The video shows a collage of how the expensive pigment Tyrian purple is made out of murex snails, and how it on various levels lives on symbolically in digital visual culture. There are a number of murex snails on the bottom of the aquarium, onto which capsules with Europium have been attached. A loudspeaker emits low-frequency sounds reminiscent of underwater noises. Here, however, the relationship is inverted: when you put on the earphones you metaphorically dive under the surface and can hear what the voices are saying.

In both an analytical and an associative way Thomas Hämén explores the relationships between people and materials, between biology and technology, and between life and death.

Ingela Ihrman

Born 1985 in Kalmar

The passion flower’s nectar-filled honey glands play a prominent part in ”The Inner Ocean” (2017–). The flower functions as a costume during a performance in which the audience is invited to suck up the plant’s sweet juice (in the form of a passion fruit soft drink). In ”Seaweedsbladet #1”, Ingela Ihrman is credited as a guest editor, but she is in fact the person behind this hybrid between a local fanzine and a Victorian publication on philosophy of nature. The magazine was handed out in Seved, a district of Malmö, and is indeed about the place itself but also about the origins of life.

Though stately, the giant hogweed plant is not indigenous to Sweden, it secretes caustic sap and people often argue that it should be eradicated. In Ihrman’s work ”The Giant Hogweed” (2015–16), however, it depicts the strong need one can have of The Other, where the knowledge of the risk of injury is overwhelmed by the senses. The short story ”Gröna fingrar” (Green Fingers), which is linked to the work, is steeped in the fog of longing to envelop and penetrate.

Ingela Ihrman’s intense interest in biological and marine processes slides into a symbiotic relationship. She makes herself into an instrument for working through charged metalevels in the subject-matter, but is also transformed into the soft bits of a mussel’s inner organs, dressed in a cloak that she made out of plastic and silk. Her bathtub back home in Seved serves as the mussel’s shell.

Exploring society and art with their bodies is an essential element in feminist performance tradition. It brings to mind “We won’t play nature to your culture” – Barbara Kruger’s phrase of non-consent from 1983. Ingela Ihrman’s reinterpretations, however, create chaos in dichotomy and category.

Sara Jordenö & Amber Horning

Sara Jordenö, born 1974 in Umeå

Amber Horning, born 1974 in New Haven, Connecticut

Sweden accepted 160,000 asylum seekers in 2015 – that is 2.5 percent of the total population. Since the government’s asylum policies became stricter and medical age-determination tests were introduced – the scientific methods and results of which have been strongly criticized by experts – unaccompanied young asylum seekers have been living with great legal uncertainty.

Sara Jordenö works with documentary projects based in society that often extend over several years. She has worked with the criminologist Amber Horning to create a new work in which activism, contemporary art and research intersect. It deals with the way the Swedish State treats unaccompanied refugee minors from Afghanistan, the stress and vulnerability that the asylum process entails and the solidarity and activism that has emerged through civil society organisations and the desire and ability of certain individuals to support the refugee youths.

The video installation bears the title ”Precarious Record” (2014–18) and deals with the subject from a legal and social perspective, at the same time as one of the affected boys’ secluded life is brought to light. Based on research conducted through in-depth interviews with refugees regarding their experiences and through collaborations with activist networks, Jordenö and Horning have created a project that addresses the full complexity of the issue.

Hanni Kamaly

Born 1988

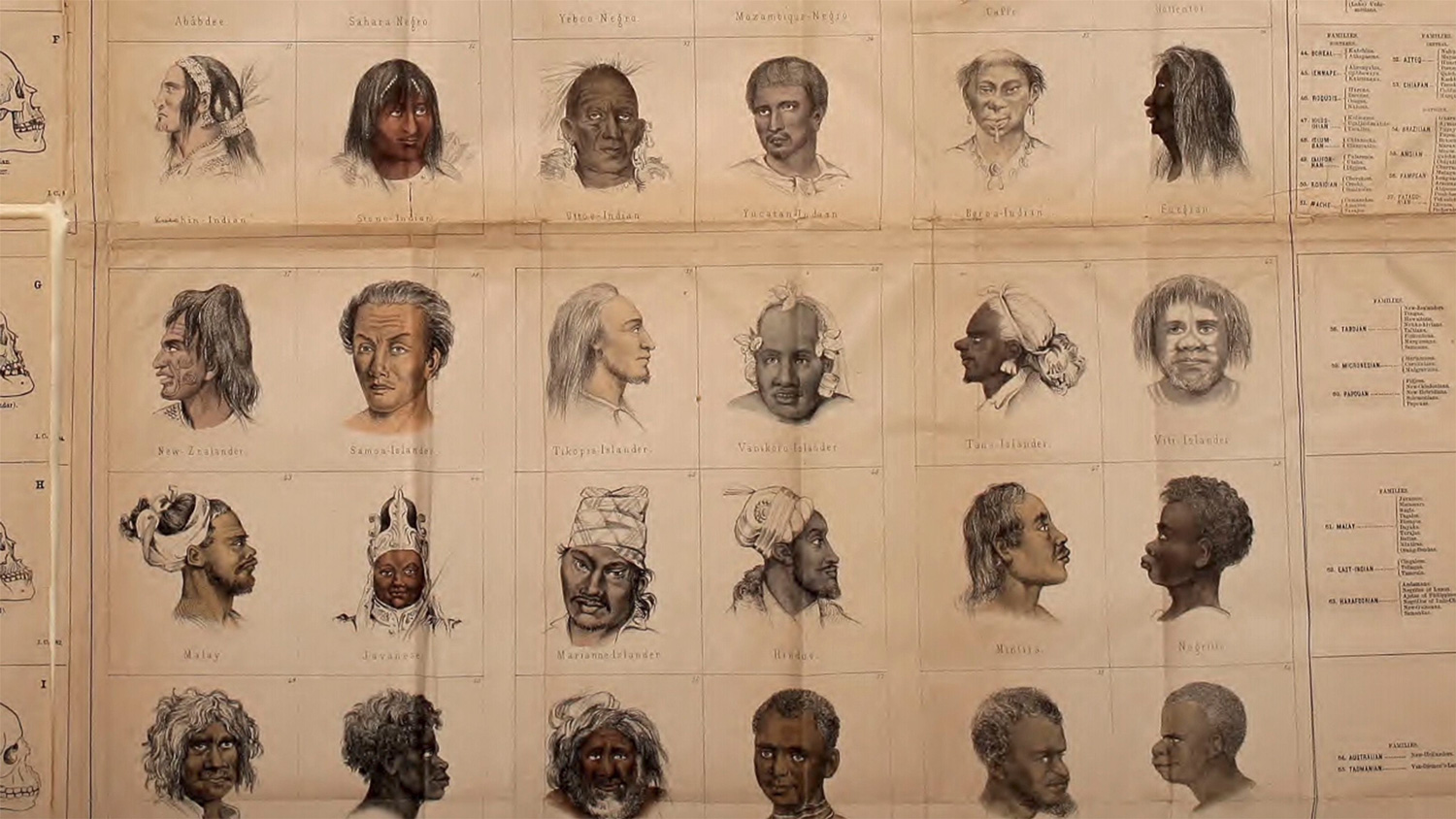

In the video work ”HEAD, HAND, EYE”, Hanni Kamaly interweaves images and stories in associative thought chains that reveal how power has always been exercised by controlling and dehumanising the body of the other. Representing the other as a wild beast or a form of vermin has been used as a means of justifying acts that would otherwise have been deemed inhumane.

The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan (1901–1981) claimed that infants initially experience their body as separate parts but that the brain, in the mirror stage, connects the fragmented body into a whole, and that this is when the Subject emerges. Kamaly’s film shows the reverse course of events, namely how the Subject is torn to pieces and becomes an Object at the mercy of authority. The title of the film names three parts of the body that are vital to our ability to manifest ourselves in the world – head, hand and eye. Throughout the ages, these body parts have been severed as punishment for breaking the rules and challenging the rulers.

The fragmented body can then be used in the ensuing process of dehumanising. The film relates, among other things, how the French colonial authorities responded to a rebellion in the Pacific kingdom of New Caledonia by beheading the Kanak chief Ataï and bringing his head to France, where it was used for ethnological studies and exhibited in museums. Racist notions continue to thrive to this day, informed by such actions.

Mårten Lange

Born 1984 in Gothenburg

”The Mechanism” (2017) is a series of photographic works that connects different cities in the world through the documentation of buildings and people in hi-tech environments where surveillance, urban life styles and belief in a technological future meet. The images are both appealing and frightening in their attempts to show how human living conditions change when surveillance technology and electromagnetic force fields form the foundation of the interconnection of people. Close-ups alternate with cityscapes and create filmic sequences of a melancholy narrative that resembles science fiction but in actual fact belongs to an ongoing reality.

Mårten Lange has published photobooks since 2007 and the bibliography of the past three years consists of ”Citizen” (2015), ”Chixixulub” (2016) and ”The Mechanism” (2017). His photographic work reveals a distinct interest in the relationship between humans, animals, nature and technology. He usually decides on an area of interest and then starts his investigations using his camera to find ‘evidentiary material’ that shows the results of his work. To him everything is of equal importance – an electronic switching station is not higher in hierarchical value than the view of a building made of steel and glass that towers above the landscape

Helena Lund Ek

Born 1988 in Stockholm

Helena Lund Ek’s art takes possession of the space and the laws of physics. Her primary medium is figurative painting, on fabrics that can be hung for several metres along walls or suspended freely from the ceiling, or down along a wall, only to spread out across the floor. Lund Ek works with painting as action, exploring the fluid boundary between art and life. Her paintings have a particularly charged presence in the room, as though imbued with their own life.

The paintings ”Lily of the Valley” and ”Hanging” came about during a period of personal loss and grieving. In many cultures, the lily of the valley, which flowers early in spring, symbolises returning to life from death. The figures in her paintings seem to hover on a level between earth and another dimension. For Helena Lund Ek, painting has become a secondary spiritual place for prayer and faith, allowing it to be a poetic possibility for transcendence.

Dinis Machado

Born 1987 in Porto

Dinis Machado operates in the interface between art and dance, moving effortlessly within both fields. In the work ”Site Specific for Nowhere”, he refers to a series of earlier works exploring materialist ideas on citizenship. ”Site Specific for Nowhere” is a choreography that was not created for a particular place but becomes specific for each site where it is staged, as it arises in close dialogue with the features of the actual location.

The work is performed by Machado himself alone, exploring the chosen space with a variety of activities, such as walking and standing, in an ever-intensifying, spiral movement. Step by step, Machado circles the place with his presence and creates a charged space within the space with his movements. Gradually, the territorial claims of his motions go from ambition to concrete fact, insisting on the right to occupy the space and belong there.

Dates and time: Performance by Dinis Machado

Éva Mag

Born 1979 in Csikszereda

A sketch drawn by Éva Mag in 2013 shows a body shaped like a four-legged being crowned in triangular headgear and with nipples pulled out to stalk-like canals. A foetus is marked with an empty circle on the abdomen of this strange woman-animal that evokes associations with both a nun’s veil and pornography. Several of Mag’s sculptures and installations portray the pressures on women’s bodies. She draws our attention to the inherent conflict in being seen as sexual territory, producing children and at the same time owning the right to being a sexual subject. The subject-matter contributes to the charge of raw energy in the work.

Other artworks by Éva Mag show the human body as subjected to extreme power and systematic violence. These sculptures of trauma are part of an overarching inquiry into the impact of political ideologies and social structures on the body. The physical aspects of working with clay are an important reason for the artist’s choice of medium – it is heavy, resistant and dirty. Other materials contrast with clay, such as the textiles Mag encountered in her parents’ sewing workshop. The humanoid and sometimes truncated eighty-kilo bodies that Éva Mag has sewn cloth covers for are sculptures in their own right, as well as being a part of ”Stand up. I said stand up!”, a performance where she tries to get the heavy yet fragile being to stand upright.

Eric Magassa

Born 1972 in Linköping

Eric Magassa’s work comes about as part of a long process – several pieces are in progress simultaneously in a wide variety of techniques, with the content migrating between them. In the ongoing photographic series ”The Lost”, a male figure appears in different outdoor settings. The figure’s head is covered by a cardboard box painted in large fields of colour reminiscent of African masks or naïve art. The artist himself is the model and initially the project consisted of the city of Gothenburg, a camera and a tripod. A residency in Detroit provided Magassa with the opportunity and time to involve more places and people, and had him developing a new working method. The title is ambiguous – a thing that has been lost, or those that are lost?

The drama and media theoretician Michael Bachmann sees points of intersection between ”The Lost” and photographs of a postmodern image-maker such as Cindy Sherman – seeming self-portraits in which the mask filters the expression. There’s a performative aspect at work here and while Sherman refers to female stereotypes, Magassa’s portraits can be read from a postcolonial perspective. Having grown up in Gothenburg and Paris with a Swedish and French-Senegalese background, he has studied how West African art has been copied and exploited in modern art as well as commercially. The original purpose of the object – be it as an initiation mask or a protective amulet – is reclaimed through the shift of meaning that takes place when the artist puts on a similar mask, or, as in other works, recreates a sculptural figure. Eric Magassa’s theatrical stagings invoke the heritage of a continent where he has some of his roots, but they also point in a new direction.

Tor-Finn Malum Fitje with Thomas Hill

Tor-Finn Malum Fitje, born 1989 in Bergen, Norway.

Thomas Hill, born 1989 in Coffs Harbour, Australia.

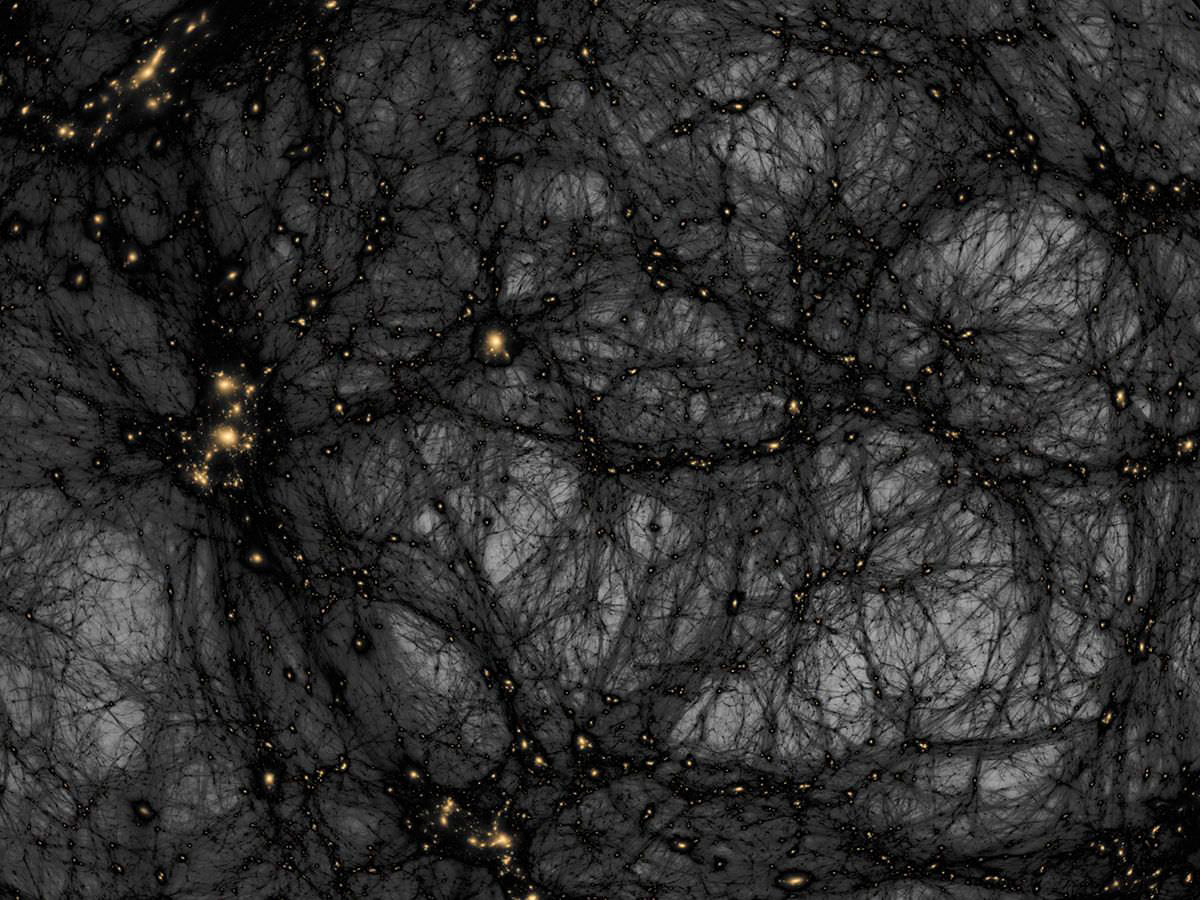

Tor-Finn Malum Fitje explores the use of metaphors in the natural sciences: not just in names, images or models representing something other than themselves, but as a cognitive process that enables us to see relationships between apparently unrelated concepts. In the essay film ”Aleph Null & The Missing Mass” he takes us on a winding journey through the history of darkness in the Western cultural sphere. The very first lines of the Bible establish that God created light out of darkness, and that light was good. Ever since then, darkness has been represented as a negation and a metaphor for evil, the unknown, and the looming threats.

In the film, the artist’s voice-over is accompanied by footage found in the abyss of fact, fiction and disinformation that constitutes the Internet. The journey begins with excerpts from art history, where artists have used chiaroscuro since the renaissance to highlight Biblical scenes set in darkness. Other artists, including Kazimir Malevich and Man Ray, have explored darkness in black monochromes and darkroom experiments. Today, theories on dark matter and dark energy have created a new sensibility for the limits of our potential understanding of the world. Fear of the new darkness and our attempts to control it leave their mark on both Hollywood and paranoid conspiracy theories on the web.

Britta Marakatt-Labba

Britta Marakatt-Labba, born 1951 during the autumnal herding of reindeer along the Norwegian–Swedish border.

The massacre on Utöya in 2011 shocked the world. When the news of the shootings reached Britta Marakatt-Labba she knew that she had to somehow approach the terrible events in order to process and understand them. She started embroidering on old wheat sacks that were stamped with the Parteiadler, the Nazi eagle emblem. The Germans had transported the sacks to northern Norway during the Second World War and used them to trade with the Samis, amongst other things. Since the sacks were durable, they came to be used as doors on Sami huts and some of them have been preserved to this day.

Britta Marakatt-Labba has worked with embroidery, Sami stories and myths throughout her artistic career. By freely embroidery the events on Utöya on the sacks she linked the Nazis’ devastating progress in the Second World War with contemporary fascist violence. Thus, she gave expression to the political events of the times at the same time as her own family history found its place in the work.

In ”Händelser i tid” (2013) (Events in Time) the embroidered sacks hang in a formation that is reminiscent of the huts of nomadic life. The work was first shown at the Lofoten International Art Festival in an old industrial building, which helped make the connection between art, handicraft and trade visible.

Fatima Moallim

Born 1992 in Moscow

Fatima Moallim lives and works in Stockholm, where she has been working on the project ”Flyktinglandet” since 2012. Her work revolves around narratives of her parents’ flight from Mogadishu in the 1990s. She expresses herself in a gentle and humorous way about the friction between the fantasies that refugees have of their journey’s end and the daily reality with its frustrations and the cultural misunderstandings and clashes they experience in the small Swedish town.

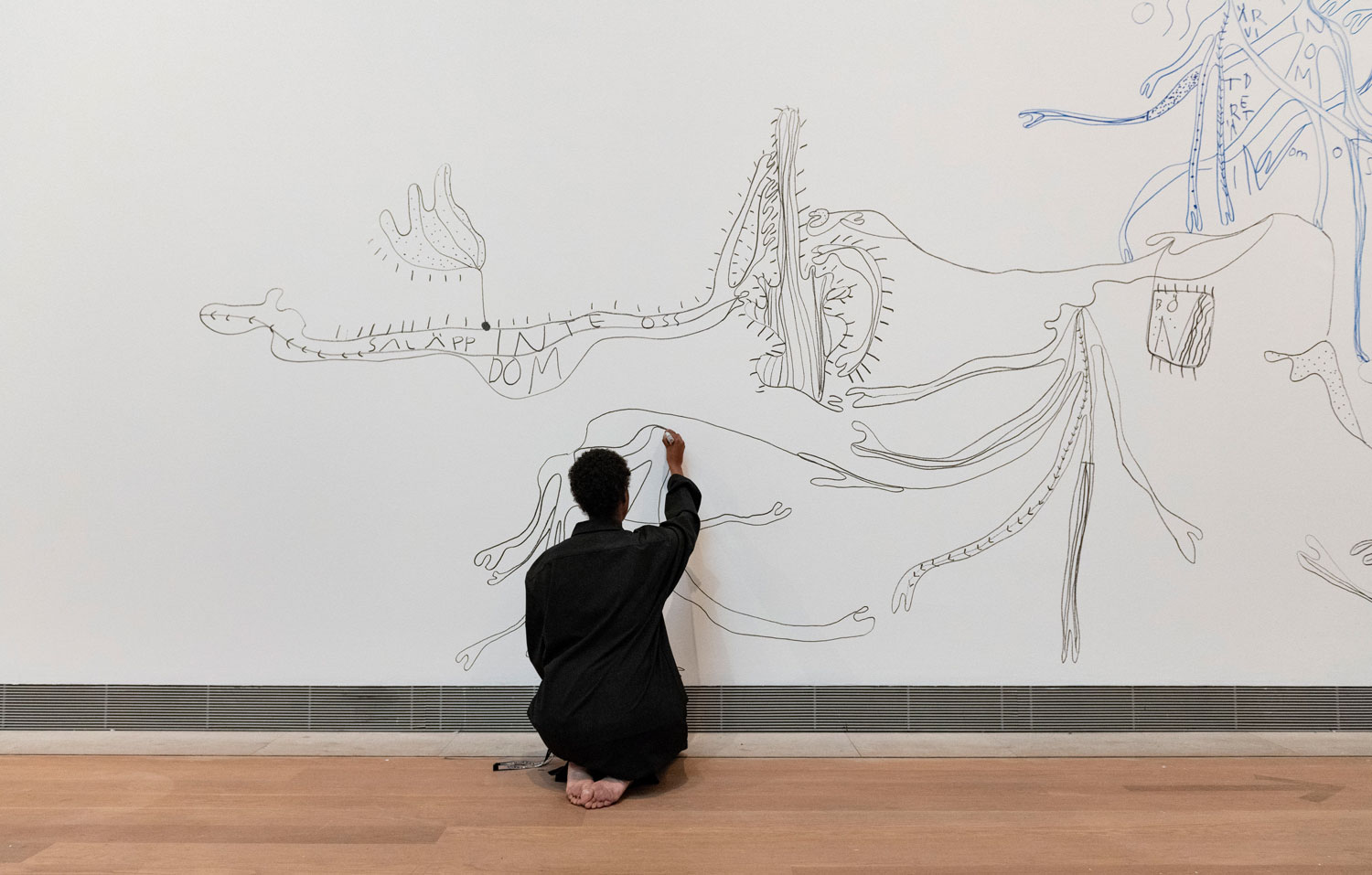

Drawing is the basis of her performance acts, in which Fatima Moallim’s and the audience’s energies merge into one. It flows out through her hand in lines where the pen’s movements express what she is experiencing in the space. With her back to the audience she hears whispers and sounds of people in the room. The act is performed in ritual silence, which the artist likens to a silent prayer. Her drawing is just as much a result of her own experiences and feelings as the audience’s energies and notions of the places that have formed her identity.

Åsa Norberg & Jennie Sundén

Åsa Norberg, born 1977 in Gothenburg

Jennie Sundén, born 1977 in Gothenburg

The focal point of ”Gifts and Occupations” (2017) is an enlarged copy of the artist Karin Larsson’s (1859–1928) plant stand from her home in Sundborn. The shelf was designed to allow all the plants to have as much sunlight as possible. Its modernist shape was ahead of its time. In Sundén and Norberg’s work, one leg of the shelf is placed in a hexagonal sandpit, as a nod to the German educationalist Friedrich Fröbel (1782–1852). Fröbel, who inspired among others Maria Montessori (1870–1952) and Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), compared a child to a plant that should be given the opportunity to grow freely and blossom. The very first sandpit was built for one of his kindergartens.

A garden trellis has been placed behind the sandpit. The sculptural objects are shown together with textile paintings. In the installation, ideas about child learning, perception, cultivating and growth are interwoven with the history of abstract art. The work draws parallels between modernism’s notions of democratic aesthetics and an egalitarian society in which, for example, childcare and free schooling are important elements.

Åsa Norberg and Jennie Sundén have worked together for a long time, both as artists and curators. They demonstrate how art is always part of both a historical context and a concrete situation in the present.

Ida Persson

Born 1985 in Malmö

The eye tends to wander across what looks like tiled structures in Ida Persson’s monumental paintings. But it is unable to penetrate beyond the surface of the towering edifices. The paintings are hung high up on the wall, forcing us to look up at them. They seem to exert an influence over us – a form of subtle violence, if you like.

In his collection of essays ”Discipline and Punish”, Michel Foucault describes how corporal punishment was abolished in favour of controlling the individual’s mind and soul. Through discipline, the body becomes docile and can be dominated by authority. Discipline requires an architecture that forces prisoners to adapt their lives to the possibility of constantly being seen.

An architecture that creates docile bodies is not only useful in prisons. It can also be used in organisations such as schools, workplaces and hospitals. Ida Persson examines the mechanisms of discipline, and gives them a painterly representation in her architectonic works. The sharp light from above and the clinically smooth surfaces evoke a sense of having nowhere to hide. We watch the paintings, but who is watching us?

Anna-Karin Rasmusson

Born 1983 in Karlstad

In her art, Anna-Karin Rasmusson scrutinises what it means to be human. Her video work ”Mater Nostra” reflects the balance of power in human relations. Dressed in a flesh-coloured body stocking, the artist surrenders her body as a projection surface for our innermost feelings and deepest fears.

We follow the artist as she drags a human-sized doll up a staircase over and over again with great effort. At the end of the stairs, empathy is put to the test. Life and death are suddenly in the hands of one person. The doll falls helplessly. Everything starts over. The papered walls of the passage are gradually covered with wet, red paint like blood in the space where the fruitless labour goes on endlessly.

”Mater Nostra” is Latin for Our Mother. Being a mother means giving life to someone with your own body and your own blood, but also being responsible for a being who is totally dependent on you. The phrase suggests the Virgin Mary, who gave birth to Jesus, witnessed his suffering and death on earth and buried his tortured body.

John Skoog

Born 1985 in Kvidinge

Young people in wide-open spaces are a filmic refrain in the works of John Skoog. Seemingly mundane moments in the characters’ lives are captured in the dusky light, while older people off-screen tell terse stories, memories or rumours. The distinctive atmosphere of his films, restrained yet acutely observant, is evoked by the suggestive soundscape.

In John Skoog’s film ”Sent på jorden” (Late on Earth, 2011) some girls are playing ball on a field, swatting away cockchafers, possibly in the same place as where cigarette smoke is rising from behind the back of a lone teenage girl gazing at the pink sunset sky in the first scene of the film. The title is taken from Gunnar Ekelöf’s poetry debut.

In ”Värn” (Defence, 2014) the camera glides impossibly slowly over a mighty construction made out of cement, strong beams of greying wood, disused railway tracks and other modern remains on the plains of Kvidinge. Karl-Göran built it as a shelter for himself with space for neighbours, prompted by a brochure issued by the Swedish government in the 1950s recommending preparedness in the population in case of new times of instability and unrest.

The films borrow techniques and strategies from the archaeology of cinema while the contents may have been inspired by authors like Birgitta Trotzig or Vilhelm Ekelund – but John Skoog’s existential inquiries are entirely his own.

Anders Sunna

Anders Sunna, born 1985 in Jukkasjärvi parish and grew up in Kieksiäisvaara in Pajala municipality.

“I was only a year old when it happened, in the summer of 1986. Although I wasn’t there at the beginning of the conflict, it’s an event that has had an impact on my entire life.” The words are Anders Sunna’s own and what happened is the story of a battle that his family has waged against both the Sami community they belonged to and the Swedish state, a conflict that has its origins in the 1940s. The struggle is about their right to engage in reindeer husbandry in the same way as the family has done since time immemorial.

Anders Sunna has used art for political agitation since he was a teenager and continued to do so when he became an art student in Stockholm. His large paintings, installations and performance pieces deal with the oppression of his family and their rights that he experienced as a Sami. Through his art he conveys the manifold feelings that he cannot express in words. Feelings rooted in the racialisation of Samis and the abuses that the Sami people have had to endure and are still forced to contend with. “I am stateless in a dictatorship”, says Anders Sunna.

Cara Tolmie

Born 1984 in Glasgow

Cara Tolmie’s works probe the site-specific conditions of performance-making via her body and voice in order to access the political and poetic capabilities of physical, written and musical languages.

Cancamon is built upon three songs – Zabelle Panosian’s “Groung”, and “There is a Balm in Gilead” and “Blasé” by Jeanne Lee and Archie Shepp. What intrigues her in this music is “the communication of the singing voice, how it can entice beyond comfortable listening”.

Throughout the work she holds these samples within her body, using taut movements and vocality to feel through the word ‘balm’ and how it might relate to the female singing voice. In her description of the performance, a cry is characterised as “somewhere between a moan, a dampened scream, an old dial up tone and the sound of a whistling kettle.”

Cara Tolmie’s ”Cancamon” is elusive yet exacting, but mainly, deeply personal. The locations where the video work was shot are revisited Stockholm grounds where Jeanne Lee performed and recorded – The Golden Circle, part of ABF (Workers Educational Association), and Borgarskolan, now Sollévi-huset, a health and treatment centre. The choice of these spaces reflect Tolmie’s own mission to place herself within the context of the sounds she both listens to and performs.

Anna Uddenberg

Born 1982 in Stockholm

A tribal tattoo on the small of a woman’s back and a renovated kitchen that looks expensive. Anna Uddenberg works with contemporary generic ornaments and aesthetics that signal words of value on the market, such as luxury, control and safety. The artist has a background in performativity theory and started out decoding and juxtaposing social scripts recognisable from contexts such as event industry and 18+ Klickbates to increase our understanding of the viewer’s role in hierarchies of power and social order. Her figurative, often hypersexualised sculptures gradually took over the role of performers and have recently been replaced by sculptures that are approaching abstraction. A wig of highlighted hair and the wearer’s exposed crotch over a very well-equipped stroller in a work like ”Jealous Jasmine” (2014), has given way to less easily defined objects in the same pale pastel colour range. Laminate, synthetic hair, Crocs, artificial nails, car interiors and carpeting are some of the materials she uses. Gone are the bodies, while the objects have become a form of consumer goods for obscure needs.

Works such as ”Cuddle Clamp” (2017) and ”Twin Generators and Upgraded Tender” (2017) resemble advanced aids for people with diverse abilities, or scratching poles for trophy wives. “I am interested in infiltrating and recoding commercial objects and environments, in taking apart and examining their concepts, forms and materials and inserting them into new dialogues with each other”, says Anna Uddenberg. Perhaps the lower back tattoo and the pseudo-genuine kitchen island will soon meet on a day channel near you.

Sophie Vuković

Born 1988 in Zagreb

“You can’t lose a home if you never had one. How can you get lost if there never was a starting point to begin with?” These words are said by a young girl reflecting on her life situation in the film ”Shapeshifters”.

The filmmaker and artist Sophie Vuković’s parents were Croatian, and she was born in the country that was once called Yugoslavia. She grew up in Australia and China, before moving to Sweden with her parents when she was ten. ”Shapeshifters” chronicles her personal journey, a seemingly endless voyage. The feeling of not belonging anywhere leads her to a search for identity and meaning. The potential for identification is explored through her relationship to nations, parents and friends.

The film speaks for everyone who feels that they exist in an “in between” state – a condition that is also represented in how the film oscillates between languages and genres. The dialogue alternates between English, Swedish, and “Serbo-Croatian”, and the cinematic style moves between fiction and documentary.

The film opened at the Gothenburg Film Festival in January 2017 and toured national cinemas in October the same year.

Knutte Wester

Born 1977 in Eskilstuna

“You see over there? Back there’s where the border is.” A child moves around in the Swedish countryside and points out an invisible border. It frames the safe areas in the vicinity of a place where he lives with other undocumented immigrants. The film’s aesthetics are pared-down and unsentimental. The boy talks about his situation without a trace of bitterness. “Sure, it would be great to go in to town and eat a hamburger, but you have to wait your turn”, he says. The film is a testimony to our remarkable human ability to adapt, while showing how unreasonable and absurd the situation is. The boy has lived within the boundary for four years.

Ever since his student years, Knutte Wester has been interested in providing a platform for people’s stories of vulnerability and loss. ”Här går gränsen” (This is the Border) is part of a more extensive installation, ”En hemlig plats” (A Secret Place), that he worked on between 2012 and 2016.

At the end of the film, the boy tries on a pair of wings. They’re heavy. “We should have made them shorter”, says the child that seems to be holding the camera.

John Willgren

Born 1985 in Stockholm

¨”Die Fahne hoch performed as a waltz”

A musician plays a slow waltz in the streets and plazas of central Stockholm. The people passing by seem to hardly notice him. What they don’t suspect is that the melody is an old German march, ”Die Fahne hoch – The Flag on High”. This song was once very popular in Germany. It was even regarded as a second national anthem during the Third Reich. Today, it is banned in Germany.

The young man with the accordion is the artist John Willgren himself. He has rearranged the melody and performs it in ¾ time. In one of the scenes in the film, we see the artist’s parents dancing to his accordion at a Swedish community centre. His mother was born in 1944, during the World War II. His father was born the year after, as a peacetime child in an era of dawning hope.

The tune may be like an echo from a distant past, but the tendencies that once made this melody so popular have once more grown strong in Europe. The post-war mantra “Never again” is not heard as often today. On the contrary, opinion polls show that one in five Swedes could vote for a party with neo-Nazi roots. The slogans may be new, but it’s the same old waltz.

Christine Ödlund

Born 1963 in Hägersten

The mysteries of life and the hidden dimensions of existence pervade Christine Ödlund’s oeuvre. She works with electroacoustic music as well as painting and installation and moves freely between science and metaphysics. ”Elektroakustiska aspekter av människa och växt” (Electroacoustic Aspects of People and Plants, 2018) is based on physicist Nikola Tesla’s (1856–1943) ideas regarding electricity and energies. His thoughts have not only found resonance in the scientific world but also in occult circles.

The installation consists of an undulating sculpture in recycled aluminium – a material with good conductivity – that communicates with a larger wooden sculpture, wrapped in masking tape. The larger one seems to be a sketch for the smaller one, although the size ratio is usually the reverse. The forms recall Tesla’s electromagnetic spools and the wave motion of electricity. Two plants with exposed roots are presented between the sculptures. The one is exposed to a clicking sound, while the other is connected to a loudspeaker, allowing the viewer to perceive any energies it may emit. Does all life have the ability to react and communicate? Is it possible to establish contact between humans and plants?