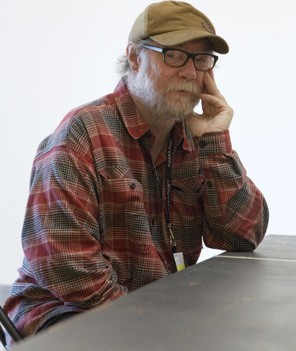

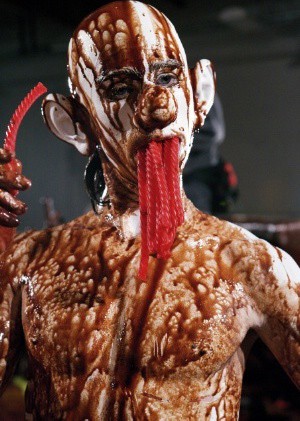

Paul McCarthy, Pirate Party, 2005 Performance photograph (Caribbean Pirates, 2001-2005 i samarbete med Damon McCarthy). Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

40 years of hard work – an attempt at a summary

Like a sports commentator, I take frantic scribbled notes on the spectacle before me. I am in the basement of the Hauser & Wirth Gallery in London, situated in what was formerly a bank, designed by Sir Edward Lutyens in the 1920s. The basement itself is an old vault and suggests claustrophobia even to someone who is not normally uncomfortable in cramped spaces. “This time he’s really gone too far,” I say to myself. But I remember thinking that even when I saw Sailor’s Meat from 1975. Of course he goes too far. McCarthy nearly always does.

In hindsight, I doubt that I was making notes to aid my memory – the scenes were so nightmarish that I probably could not forget them even if I tried. On the contrary, it was an attempt to distance myself from what I was witnessing. For McCarthy’s works are so invasive, frightening and loud that all critical detachment appears impossible. Prior to being in this bank vault, I had met and worked with McCarthy on several occasions. I knew him to be one of the most sympathetic, modest people I’ve ever met – erudite and attentive, a teacher who promotes his students, a successful artist who speaks in glowing terms of the artists who inspired him. This has been pointed out in most articles on McCarthy and is worth repeating since his art is so overwhelming that one easily confuses the man with the work.

What he does, the bacchanalian chaos he generates and the terror and lust he arouses in most onlookers, is the result of an exceedingly conscious oeuvre – 40 years of hard work. Even if his method and oeuvre leave room for improvisation and intuition, they are by no means the work of a madman – this is obvious to anyone who is familiar with him and his place in art history, but to the uninitiated visitor who is confronted with his work for the first time it can be worth pointing out. Nor are these the autobiographical attempts of a disturbed mind to come to terms with his own personal problems. Paul McCarthy’s works incorporate a sharp social critique, which focuses on social and cultural traumas rather than on private issues. This is the dark side of the American Dream, of the consumer society we all live in, even in Sweden and the rest of Western Europe. He also touches on a variety of existential issues. But he can also be exceedingly comical, although the laughter often sticks in your throat. He is a clown, a buffoon in the Rabelaisian sense – his burlesque, dark humour has the subversive edge and undermining character that the Russian linguist and critic Mikhail Bakhtin specifically distinguishes in his book on Rabelais.

McCarthy has been inspirational to several generations of artists and pioneered methods that are fairly common today. His way of creating sculptural video installations out of the sets he used in performance works, for instance, has been adopted by many others. Artists who have been considered influenced in one way or another by McCarthy include Cindy Sherman, Mike Kelley, Jason Rhoades, Jonathan Meese, John Bock, Jake and Dinos Chapman, to name a few, often referring to their fascination for the abject, for Dionysian excesses and a penchant for overloaded, baroque or grotesque aesthetics.

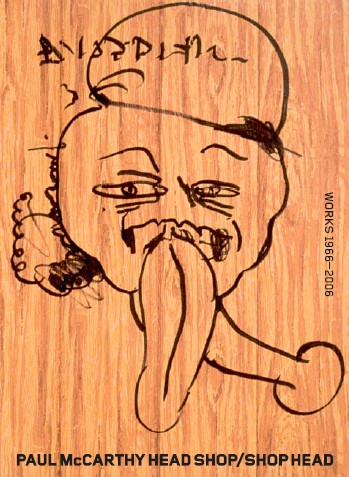

Paul McCarthy moves in and out of his own oeuvre in a way that makes it hard to discern the chronology. Many themes return throughout his production, from the early years at art school to the present day. He repeats and recreates many works, and the repetition and translation, the transferral of certain works into other media, has emerged as a theme in itself. He also occasionally executes a work twenty years after making the preliminary sketches. For this exhibition he has created works based on ideas from the numerous notebooks he has amassed since the late 1960s, containing instructions for sculptures, videos and performances. Sometimes the same idea pops up more or less unchanged year after year. This repetition and recycling reflects his open attitude to the works – they are in a state of transformation. McCarthy sometimes engages in large projects where the works are incorporated in an ongoing process that alters previous presentations, since they merge with a constantly growing context. Therefore, neither the exhibition nor this essay are primarily arranged in chronological order, but more according to the subject matter and theme. However, in order to outline some sort of development process, I have divided the essay into three main sections that correspond to three periods in McCarthy’s oeuvre: Starting points (1966-1973) deals with several of the themes he processes throughout his work; The performance years (1973-1984) describes the period when McCarthy worked with audience-attended performance art and developed certain key themes that later recur in his work; the final section, Mechanical ballets, sculptures and video installations (1984 – ), accounts for the work method that McCarthy still uses today. In 1984, he stopped doing performances which were focused on a live audience. After a few years of exploration, he started working with (often mechanical) sculptures and with large-scale film and video productions in which he expanded on his performance works and also involved other actors and used more elaborate sets. This essay attempts to provide an overview of his oeuvre and is complemented by two essays that delve deeper into particular facets: Iwona Blazwick writes about McCarthy’s figurative sculptures, while Thomas McEvilley studies his performance and video works.

Starting points (1966–1973)

When Paul McCarthy embarked on his art studies, which he began in Salt Lake City (1966-68), followed by San Francisco (1968-69), and finally in Los Angeles (1970-73), the art scene was dominated by a handful of approaches: abstract expressionism (even if it was past its climax many artists still related strongly to it), conceptual art, minimalism, pop and experimental film. Many have pointed out that McCarthy’s work is rooted in all these styles and mediums, which are mutually different in many respects, even though they share certain preoccupations and issues, something that is revealed in McCarthy’s way of relating to them. All these schools are present in various aspects of his art, even early on in his career. As McCarthy claims in an interview, he did not evolve from painting as action to performance to sculpture; on the contrary, he saw these as parallel, concurrent and intimately related work methods.

Painting as action

In abstract expressionism, it was above all “the legacy of Jackson Pollock”, action painting, that interested McCarthy. He emphasised painting as action rather than as product – an aspect that was equally crucial to the Fluxus artists and others who engaged in happenings, or what we today call performance art. At the University of Utah he produced his Black Paintings (1966-68), smearing paint, oil and earth on the canvases and wood panels with his hands and then dousing them in paraffin setting fire to them. Following this, in San Francisco, he spent a period working with silver paint with which he covered the ground, newspaper and countless objects. Everything he coated was appropriated and became part of his work.

In 1966, he acquires a copy of Allan Kaprow’s volume Assemblages, Environments and Happenings (1966) and becomes aware of the Japanese Gutai group, Tetsumi Kudo, Wolf Vostell, and the happenings of Allan Kaprow. The same year, he finds out about the performances of Gustav Metzger and Ralph Ortiz. Jackson Pollock, Yves Klein’s Anthropometries (impressions left by nude female bodies covered in Klein’s patented blue pigment), Nam June Paik, who dips his tie in paint and uses it as a brush, and John Cage who drives a car across paper in Robert Rauschenberg’s Automobile Tire Print (1953), are some of the artists that worked in this spirit, though not all of them were known to McCarthy at the time. For McCarthy painting is intimately linked to performance, and in several of his earliest works that were documented photographically or on video McCarthy appears in the role of an action painter, as in Face Painting – Floor, White Line (1972), where he shuffles across the floor with a tin of white paint in front of him, dragging his body in the paint, and Whipping a Wall with Paint (1974), in which he dips a blanket in thin paint and flings it around and against the walls. Or Penis Brush Painting, Windshield, Black Paint (1974), where he dips his penis in paint and paints a windshield, in parody of the action painters. Variations on this theme recur in many of his performance works over the years, most specifically, perhaps, in Painter (1994), but also in, say, Bossy Burger (1991), Tokyo Santa (1996) and Piccadilly Circus (2003).

In between language and action – conceptual art and performance

In this borderland between conceptual art, performance and sculpture, the relationship and parallels between these superficially different phenomena is revealed. This is in evidence in many artists in the 1960s and 1970s, but is especially pronounced in the works of Paul McCarthy and Bruce Nauman. In an essay on Bruce Nauman, Janet Kraynak highlights the pragmatic linguistic philosophy originating in the British philosopher and linguist J.L. Austin’s theories on “speech acts”. By speech act Austin means a statement that is not solely descriptive but also constitutes some form of action. A promise, for instance, is a speech act. This approach to language as a performative tool fascinated many artists operating in the intersection between conceptual art and performance, including Bruce Nauman, Lawrence Wiener, Allan Kaprow and the Fluxus artists Yoko Ono and George Brecht. This does not mean to say that they were directly influenced by, or attempted to illustrate, Austin, but it does clarify the connection between conceptual art and performance-based art. One forerunner is John Cage, who replaced conventional graphic notation with terse, typed instructions in words and numbers.

Minimalism

In recent years, McCarthy’s early interest in minimalism has been the subject of numerous essays and interviews. On a superficial level, his art would appear to be the antithesis of minimalism – reduction and purity are not exactly the first thing that springs to mind with McCarthy. Many of his earlier works, however, have clear references to minimalism, and on a conceptual level this permeates his entire oeuvre. The most famous example of this is Dead H (1968/1975), a sculpture made of galvanised steel in the shape of the letter “H” (as in Human), prostrate (dead) on the ground. It is open at both ends, and you can bend down and look right through the sculpture. What you cannot see is the part of the ‘H’ that joins the two stems, the centre – or stomach, if we pursue the anthropomorphism of the title. The sketches for the work include notes indicating the importance McCarthy attributes to the non-visible part of the sculpture, what he calls “the intangible inside”. The same unreachable interior is found in Skull with a Tail (1978), a black cube with something resembling a ventilation shaft attached to the lower part. The shaft is open at one end, but since it is bent at a right angle it is not possible to see right through it.

McCarthy takes the minimalist cube – which is always empty in traditional minimalist art, not only literally, physically, but also metaphorically, in that it does not refer to anything but itself – and endows it with allusions to the human body, as inferred already by the titles, Dead H and Skull with a Tail. The cube transforms into a receptacle for something human, the outer shell representing skin, a thin membrane separating the elusive inside – meat, blood and guts, but also thoughts, feelings and ideas – from the outside world. This theme is repeated in Ketchup Sandwich (realised as variations in the 1970s, 1980s and in 2006), which consists of sheets of glass stacked up to form a cube. Between the sheets McCarthy has poured ketchup that is squeezed out by the weight of the glass. Here, the hollow, minimalist cube is replaced by a cube with its contents leaking – and the ketchup most obviously symbolising blood. This was the first work in which McCarthy used ketchup, an ingredient that was to become something of a trademark for him. Vented Cube, found in a drawing from 1975 but never constructed, is imagined as a minimalist cube with rows of vents built into the sides, for air to pass through, like a ventilation box. The venting suggests some form of inner pressure or odour that needs to be aired out – an image McCarthy uses to describe his art as a whole: “You may understand my actions as vented culture, you may understand my actions as vented fear.” Allusions to minimalism are also found in works such as The Three Boxes, (1972-1984) and The Trunks (1984), which utilise the minimalist cube as a shape but also present its opposite, filled as they are with content, meaning, history. The same applies to The Box (1999) externally shaped like a huge wooden crate, but inside containing an entire copy of his studio. The minimalist cube is also inferred in titles such as Brain Box, which refers to the skull as a box to hold all our thoughts and feelings.

Looking Out, Skull Card (1968) is a simple piece of cardboard with two holes signifying the eyes. It is suspended in the air by a nylon thread. In her essay, Iwona Blazwick links this early work to McCarthys later use of masks in his performances. The masks have multiple purposes. They enable the artist to assume a persona – a role. These masks can be bought in toyshops or costume and gag shops and thus belong to popular culture, consumer society. They conjure up the B-horror movies that fascinate McCarthy – a mad serial killer is even more frightening in a smiling mask. The masks can portray American presidents or comic book characters, stereotypes with no facial mobility.

McCarthy also uses dolls, stuffed animals and mannequins in numerous works, including performances, videos and sculptures. His focus on the tension between the outside and inside of the sculpture (and the human being) is thus expressed in both abstract and figurative works and is something of a dominant theme in McCarthy’s oeuvre. Hanging Hollow Torso (1966) consists of a doll with head, arms and legs missing. Through the holes where these once were attached we can look into the empty, hollow body. Body Cave (1990) is a plaster cast form of a lower body. Also his monumental inflatable sculptures consist mainly of inner emptiness. Admittedly, the most famous example, Blockhead (2003), a 35-metre tall Pinocchio figure with a cube for a head exhibited outside Tate Modern in London, contained gigantic fans, a steel structure and a candy dispenser; but on the whole, these inflatables are basically air filled balloons.

Falling – on losing control

At his art college in Utah, McCarthy heard aboutYves Klein throwing himself headlong off a five-metre high wall. In an interview he describes with great self-irony his own miserable attempts to imitate Klein’s action. How he jumped from a high window as an art act, with his feet first since he had not actually seen the photograph himself and therefore had no conception of Klein’s elegant swan dive. It was not until much later that he learned that the photograph was composited. McCarthy also ran down a hill that got steeper and steeper, accelerating until he fell over. Too Steep, Too Fast is a performance that he later also presented as an instructional work: “Run Down a Hill. The angle of the hill should increase so that one has the sensation of falling” (1968, 1970, 1972). In Mountain Bowling (1969) McCarthy rolls a bowling ball down a hill. Both works incorporate an element of immediate physical peril, and the contrast between the dry, factual instructions and the performance of the work is almost comical. To run down a steep hill is to expose oneself to a situation of losing control.

This theme permeates McCarthy’s entire production. It is manifest in several of his filmed performances from the 1970s, for instance Spinning (1970), in which he spins round with arms extended in a rather diminutive room where his arms soon smack into the walls. It is also tangible in many works with a labyrinthine architecture and rotating or overturned spaces, such as the photographs Inverted Hallways and Inverted Rooms (1970), where the symmetry of the images prevents us from noticing immediately that the photographs have been mounted upside down; and the previously mentioned sculpture The Box. Variations on this theme include the rotating rooms or cameras, as in Picabia Love Bed, Dream Bed (1999), inverted cameras that confuse our senses, alter our spatial perception, and movements that create or reflect altered states of consciousness. The loss of control also recurs in the movements and words that are repeated like mantras in his performances and appear to put the artist in a trance. McCarthy appears, moreover, to be out of control in many videos where he acts hysterical, comical and pathetic, but where this can suddenly turn nasty, in the way that alcoholic, violent men sometimes go too far. The latent violence that sometimes breaks out always appears senseless and baffling – unlike the violence we encounter in the entertainment industry, media and politics, which people try to explain and sometimes even to justify.

The formative power of social – and political – society

Abstract expressionism and minimalism help to define McCarthy in relation to art history, but how much do these terms really say? To McCarthy and many other upcoming artists in the late 1960s the tumultuous events in the world were at least as influential: the Vietnam War, the emerging youth culture, the counter-culture, rock music. Paul McCarthy was drafted into military service in 1969 but refused induction. While awaiting the court verdict that eventually gave him the status of conscientious objector in 1972, his freedom was curtailed. As an objector he had to do community service instead. Asked what his qualifications were, he said he was a film-maker. This temporarily gave him a job that involved making video tapes in a mental hospital. He later worked with gang members in Los Angeles and taught them how to make videos. Like many others during this period, McCarthy was interested in child-rearing, pedagogy and education, believing that early child development formed one’s concept of reality. The late 1960s in the USA, with its optimism and its civil rights movement, can in some ways be described as an enlightenment project with utopian traits. Discussions could touch on the sociologist Erving Goffman (The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, 1959) and his theories on the socialisation process, on how identity is created – a process Goffman describes as learning different roles. His terminology often borrowed imagery from the stage (“scene”, “props”, “audience” etc.). The same fascination for how the individual is constructed is revealed in many of McCarthy’s works, for instance in Family Tyranny (1987), where he plays a brutal father who force-feeds his son, or Pinocchio Pipenose Household Dilemma (1994), based on the classical story of a man who, for lack of a real son, makes a doll for himself that comes to life. But when the child, the doll, starts to develop its own will it is punished. In contemporary Western society, and especially in the USA, the entertainment industry has assumed the task of bringing up and educating the young and of disseminating collective values and norms, and consequently, in works like Bossy Burger (1991) McCarthy appears as an infantile, clown-like educational presenter of a kids’ TV programme who quickly loses the plot.

At an early stage in his career, McCarthy zoomed in on destructive art, where creating and destroying coincide. Saw/Hammer (1967) is one of his first performance works. On stage he and a friend smash up furniture to the accompaniment of “noise” music by a local rock group. They run amok with a hammer, a saw and a chainsaw and finally McCarthy falls off the stage. This performance generated one of the first surviving sculptures, Mannequin Head and Squirrel. This was the year after Gustav Metzger’s famous seminar “Destruction in Arts Symposium” in London, in which Wolf Wostell and Ralph Ortiz also participated. Metzger lectured at the art school where Pete Townshend was a student. Townshend was the guitarist in The Who, and his appearances were not wholly unlike the performance art of the time, especially when he smashed his guitar on stage, as Jimi Hendrix would also do a year or so later. Back home in Utah, Paul and his wife Karen McCarthy and friends formed The Up-River School, an art-collective that operated on the boundary between performance, art and music. They created parties and performed at events. Paul arrived at the name from a dream, and it reflects the group’s ambition to go against the stream. The growing interest in art as action in the late 1960s was linked to a more fervent interest in politics. That does not mean to say that this art should necessarily be interpreted as political, but one could justifiably claim that time as a phenomenon was beginning to be conceived as real, in the sense of the time it took to stage a performance, or the time it took to walk round an minimalist sculpture, or the time it took to see a video work – but also the time in which a work of art was created and to which it belonged – and on which it commented. The (impossible) timelessness on the Parnassus was no longer worth hankering for.

The performance years (1973–1984)

Around 1970 to 1984, McCarthy worked mainly with performance art. This was a pivotal period and many of the works are famous even though they were only seen by a handful of people. This was when he developed his unique approach as an artist. Performance and video have been intimately related ever since the first portable video camera, Sony Portapak, was launched in 1965. It was especially useful for documenting performances. Like many other artists, McCarthy worked performatively – sometimes alone, sometimes with a cameraman in the studio, and sometimes with a live audience. In his earliest works he performed primarily alone, and the artist’s body was the focal point. These performances were usually relatively straight-forward, terse affairs, some of which can be seen as enactments of an instruction – there are clear parallels with Bruce Nauman’s veritably choreographed movements, or with early works by Vito Acconci, all of which operate on the boundary between conceptual art, minimalism and body art, as described previously. Ma Belle (1971) is the first work where McCarthy uses a persona. The camera hones in on a telephone directory that McCarthy is leafing through. He pours oil on the pages, dabbing at them with cotton wool, all the while humming and babbling like a baby, more and more intensely, until he is verging on hysteria.

This role play, together with the use of masks and “costumes” and various props, is typical of McCarthy’s mature performance period. Another aspect of the role play in McCarthy’s performances is when the artist alternates between male and female roles, enacting and investigating forbidden and repressed territory, including unconventional sexuality, but also excrement and other body effluents – the things our severely potty-trained Western culture does its utmost to suppress. In Sailor’s Meat (1975), McCarthy appears in a blonde wig, eye shadow and underpants on a bed in a shabby hotel room. In bed with him is a lump of raw ground beef that he alternately caresses himself with, alternately straddles and tries to penetrate. He stuffs a hot dog down his pants and puts his penis in a hot dog bun. In another video, Tubbing, recorded the same evening, he is in a bathroom, sucking a hot dog, drinking ketchup and rubbing himself with hand cream, stepping in and out of the bathtub. On one occasion he seems about to throw up. The takes are long, and the feeling of disgust makes it hard to watch them to the end. The hardships McCarthy puts himself through have induced comparisons to the Vienna Actionists (Hermann Nitsch, Otto Muhl, Günter Brus and Rudolf Schwartzkogler) and to Carolee Schneeman. Thomas McEvilley instigated these associations in his seminal essay “Art in the Dark”, in Artforum, in 1983, in which he points at several topical similarities. He compares the works of these artists with religious rites, and the artist’s role with that of a shaman. On the one hand, there appear to be fundamental differences between McCarthy’s mediated, obviously theatrical performances, and those who were interested in performance as real events rather than as representational or symbolic. Chris Burden, for instance, has himself shot at for real in Shoot (1971). On the other hand, one could say that McCarthy presents the mediated, the enacted, just as frighteningly, as realistically as if it were indeed “real” or “authentic”, thereby cancelling out or repudiating the difference – which makes him postmodernly ironic rather than modern and heroic. The straight-faced instructions for archetypal myths, fertility rites and sacrifice are replaced here by references to the modern myths, produced by Hollywood and Disney. A similar parody is found in Bruce Nauman’s blinking neon work proclaiming that “The True Artist Reveals Mystic Truth”. One is forced to accede, however, that McEvilley’s analysis does reveal connections and possible interpretations that transcend the consensus that so easily arises when attempting to fit an artist’s oeuvre into art history.

The role of the audience

The role of the audience or onlooker in McCarthy’s work is worth noting. In Death Ship (1981), the audience is instructed to wear a sailors hat and sit in chairs arranged in the shape of a ship, and thus becomes part of the work. This recurs in later works such as Pinocchio Pipenose Household Dilemma. In order to watch the video, the viewer has to put on Pinocchio’s clothes and sit alone in a little booth. In San Francisco, Shithole of the Universe (1980), a performance shown in San Francisco, the audience regards McCarthy on a monitor while he himself is hidden behind a wall, where he sits beside a large man and whispers in his ear. In a loud voice, the man repeats McCarthy’s insults to the denizens of San Francisco and challenges them to come over the wall and beat him up, calling them cowards and referring to the city as the shit hole of the universe. Out of McCarthy’s last live performances Inside Out Olive Oil (1983) is particularly noteworthy. McCarthy built a huge body, a torso out of transparent plastic on a frame of rods. He writhes through the body smeared in mustard and ketchup, wearing a large rubber head mask of Popeye’s girlfriend Olive Oyl.

In 1983, McCarthy stopped doing live performances. Even if his previous performances often had only a diminutive audience, and although he continued to produce filmed enactments that resemble performances, this appears to have been a momentous decision for McCarthy. He packed all the remaining props he had used in performances from 1973 to 1983 in six trunks and shut them up. The suitcases then became a sculpture, The Trunks (1972 – 1984), which was included in several exhibitions – always with the trunks closed. McCarthy then had the idea of replacing himself (as the performance actor) with sculptures. His first attempt to create a performative humanoid, was Human Object (1982) – a rudimentary mannequin with a featureless head with only a mouth, a box-like torso with a dildo in place of a penis and a rubber sex toy vagina. The audience is encouraged to talk to the object and can feed the mannequin, the food or drink dribbles through the body and runs out through an orifice. His idea of replacing himself with a machine can also be interpreted symbolically/metaphorically. Eva Meyer-Hermann asks in an essay, “Is that what remains, a mechanical spectacle that defines both the inner and outer world? What remains of the world when myths have been unveiled?” In 1992 he opened the Trunks and photographed the objects inside: rubber masks, ketchup bottles and jars of mayonnaise, knives, toys, kitchen utensils, mutilated dolls, and so on. The photographs, Propo (1992) were exhibited together with The Trunks. He then stood the sculpture Human Object on top of The Trunks, forming a totality, a “closure”. Nowadays, the three works are always exhibited together in this way.

Mechanical ballets, sculptures and video installations (1984- )

The first mechanised sculpture, Bavarian Kick (1987), consists of a metal tube base housing the mechanical works, and supporting two stick figures with iron rods for legs, round balls for heads and equally round, red clown noses. One is dressed in Lederhosen, the other in a dress, the figures are behind separate doors, and glide out towards each other, and kick straight legged while toasting with jugs of beer. His sculptures later became more technically advanced, at times incorporating technology and special effects from the American movie industry. The Garden (1992), for instance, includes fibreglass trees from the TV western Bonanza and rubber heads used in Hollywood movies.

Pop

In the 1990s, McCarthy created several sculptures with an aesthetic influenced by Disney and firmly rooted in pop art. Bear and Rabbit (1991), Spaghetti Man (1993), Mutant and Tomato Heads (1994), and Apple Heads on Swiss Cheese (1997–1999) are large sculptures that resemble overgrown toys or teddy bears but, in McCarthy’s inimitable way, are twisted parodies of ostensibly innocuous, cute playthings. Spaghetti Man is a rabbit in a boy’s body with a 12-metre long, soft rubber penis that lies in coils on the floor. On closer inspection, the gender is less certain, since the penis appears to protrude from a hole, like paint from a tube. Is this a penis, is it something (spaghetti?) that is penetrating the figure, or are those the innards falling out? As Amelia Jones remarks in an essay, McCarthy’s works reveal a penis obsession, but the penis is never erect, and in his sculptures it is always detachable. Masculinity is thus under the threat of castration, its boundaries are dissolved and ephemeral. Maleness appears pathetic rather than macho and heroic. With regard to Tomato Heads, McCarthy mentions in an interview that he was interested in DNA research, gene manipulation and computer software for image enhancing that enables the user to change a figure into something else, something monstrous, at the click of a button. The imagery is redolent of the kind of simple, clear-cut figures one could find in an amusement park such as Disneyland. Pop culture references are also found in a series of sculptures that appropriate Jeff Koons’s famous work portraying Michael Jackson and his pet monkey Bubbles. Koons’s sculpture, in turn, can be said to paraphrase kitsch 18th century statuettes, and McCarthy’s versions of the two kings of pop (Koons and Jackson) enhance both the kitsch and the slightly monstrous, surrealist element. But he has also taken appropriation and plagiarism one step further – in the spirit of pop art, Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1999) is produced in several versions, where the shiny fibreglass surface has been painted gold, black or white. Added to this are the Michael Jackson sculptures in bronze, carbon fibre and the altered, distorted versions, like Michael Jackson Fucked Up Big Head Carbon Fibre Blue (2005). The mutations appear endless.

Hollywood

To one who has only seen Paul McCarthy’s works exhibited in Europe, it is somewhat of a revelation to visit one of his studios in the Los Angeles area. Even if we already sensed the importance of the location for McCarthy’s works, this becomes adamantly clear on driving past the film studios and workshops where they build the movie sets. This is where the dream factory lies. Many LA artists besides McCarthy have earned a living temporarily or had a side-job in the Hollywood movie industry. In an interview he stresses that this location has probably meant more to him than the work of certain artists: “The use of ketchup and masks grew out of my work and not out of being conscious of their work. I was pretty aware that certain artists were doing stuff like that. I think I found out about the Viennese in the early 1970s. Vienna is not Los Angeles. My work came out of kids’ television in Los Angeles. I didn’t go through Catholicism and World War II as a teenager, I didn’t live in a European environment. People make references to Viennese art without really questioning the fact that there is a big difference between ketchup and blood. I never thought of my work as shamanistic. My work is more about being a clown than a shaman.”

As a performance artist, McCarthy progressively moved towards larger and more complex works involving role play and props. The fact that he took the step into film and video works using sets and sometimes several actors appears only natural. His first work in this vein is Family Tyranny. But even if Hollywood is an essential backdrop and a context for McCarthy’s work, his method and expression are obviously wholly different to those of the Hollywood production. When McCarthy invited his artist friend Mike Kelly to participate in the work, his only instructions were: “I’m the father, you’re the son.” Bossy Burger (1991) is the first of McCarthy’s works for which the video set was preserved as a sculpture/installation. The shabby, grimy, primitive set, which was given to McCarthy from a television studio, bears distinct marks of his antics. It had originally been used in the old TV sitcom Family Affair. In the video, McCarthy wears an Alfred E. Neuman mask, clown shoes and a cook’s outfit. Like practically all of McCarthy’s characters, he appears to be captive in the setting. The architecture is a sealed world that restricts the actors’ possibilities and movements. The figures McCarthy plays do their utmost to break open the architecture. They attack the walls with drills, saws and other instruments, to open new windows – peepholes against which they press their faces. This is a theme that fascinated McCarthy even in his earliest performance works, with titles that eloquently describe what they are all about: Making a Window Where There is None (1970), Pounding a Line of Holes in the Wall with a Solid Steel Rod (1970), Plaster Your Head and One Arm Into a Wall (1973). In the 1990s, McCarthy also performed numerous works jointly with Mike Kelley. The installation Heidi: Midlife Crisis Trauma Center and Negative Media-Engram Abreaction Release Zone (1992) juxtaposes corrupt culture with pure, innocent nature. The sick girl lives in the city and the healthy Heidi lives in the alps. But it all goes horribly wrong, the old grandfather and Peter have unclean thoughts (which they don’t hesitate to put into action), and Heidi gets a tattoo. The tattoo is a reference to the rigorous theoretician (and practitioner) of modern architecture, Adolf Loos, who writes in Ornament and Crime (1908) that the wish to decorate is unsound and degenerate – an inclination in which only criminals and “savages” can indulge. The work consists of sets, sculptures, paintings and a stuffed goat. It also includes an hour-long video, Heidi (1992), which is now considered to be a classic. Fresh Acconci (1995), An Architechture Composed of the Paintings of Richard M. Powers and Francis Picabia (1997) and Sod and Sadie Socks (1998) are other major collaborations with Mike Kelley. A common denominator is the vast array of references to phenomena which may appear at first glance to be disparate and impossible to consolidate, but which are interwoven in a form of paranoid chain of associations, into a critique of both highbrow and lowbrow culture and the norms and values that shape the individual. “Serious” art, not least, is exposed to breakneck parody, an element that recurs in McCarthy’s Painter (1994), one of his most comical and hysterical video installations. Sporting a blond wig, he paints, bickers with his gallery owner and stumbles around in clown shoes and what appears to be a painter’s smock or a hospital gown – but without pants.

Since the early 1990s, McCarthy has explored roles and themes relating to the mythos of popular culture: Pinocchio, Santa Claus, the Western, pirates. The Western theme is part of the mythology of American history, with an accoutrement of stereotypes that have been established through countless Hollywood productions. Saloon Theater (1995–96), Saloon Film (1995), Yaa-Hoo Town and Bunkhouse (1996), F-Fort (2003–2005) and Wagons (2003–2005) are all works that focus on the wild west of the movie world. Caribbean Pirates (2003-2005) a project comprised of The Frigate, The Cakebox, The Houseboat and The Underwater World and video works, Pirate Party (2005) and Houseboat Party (2005). This piece, which is loosely based on the Disneyland attraction Pirates of the Caribbean, is a collaboration that Paul McCarthy and his son Damon McCarthy have been working on for several years. In addition to McCarthy himself, the later works feature other participants, including professional and non-professional actors. To enter the hall where the enormous reddish-brown fibreglass pirate ship, the house-boat and the mechanical Underwater World is rocking up and down and sideways, is like descending into one of the circles of hell. But there is plenty of jovial and burlesque buffoonery, along with rage, disgust and terror. The pirate ship is strewn with silicon arm and leg prostheses, with hoses that have been filled with film blood. Projections of the pirates’ ruthless orgies of brutality, gluttony and sex are shown on the walls and in the adjoining rooms. Both the Western projects and the pirate project can be read as a criticism of colonialism and global capitalism – cowboys, pioneers and pirates who venture to unknown regions where they can engage unseen in plunder, rape and torture. In the Western project Paul and Damon McCarthy only issue a few simple instructions and then step back to let the “soldiers” film one another – the chaos is built into the structure and things quickly start to get out of hand.

In the historiography of modern art, the principle of reduction is highly thought of. Paul McCarthy’s aesthetic, however, tends in the opposite direction, and this in itself constitutes a criticism against the modernist striving for purity. His large-scale projects in recent years consist of three huge installations, numerous sculptures and drawings, tens of thousands of photos and more than one hundred hours of video. It may seem remarkable that such a baroque stream of images can maintain such a consistently high quality.

In McCarthy’s kitchen we discuss the physical invasiveness and looming danger of the enormous installation The Underwater World. McCarthy who has periodically made a living as a construction worker and knows about the forces involved, says that many museum visitors today don’t realise that they need to be cautious when they approach an enormous mechanical work such as this. I mention Chris Burden’s monumental sculpture with a balancing steam roller, and some of the works by Bruce Nauman and Richard Serra, and ask if he believes these overwhelming sculptures which evoke physical sensations are typically American. McCarthy refutes this and insists that he is not a macho artist. But he relates a short anecdote about an encounter with a sculpture by Richard Serra, and the gist of the story, I believe, has some relevance to his own work:

In an almost empty museum McCarthy enters a square gallery with doors at both ends. From each corner of the room a mighty iron sheet juts out diagonally to the middle of the gallery. They don’t quite meet but leave a relatively narrow passageway. In the gallery he meets one other visitor, who sniffs and shakes his head disdainfully, looks at McCarthy and asks, “Is this supposed to be art?” McCarthy replies, “What I find interesting is that it appears to me that the only thing holding these enormous iron sheets upright is the corners of the room.” The man stops dead, regards the iron sheets that probably weigh several tons, sees how they are wedged into the corners of the gallery – turns on his heel and runs out. “I think he got it!” McCarthy chuckles.

Perhaps this physical reaction, the realisation that the work before us is potentially dangerous – is a veritable sign of actually having understood the work – and perhaps this also applies to the feelings of disgust, terror and laughter – that most of us experience immediately when confronted with many of McCarthy’s works. While being redolent with art historic influences and current political references, more than anything they hit you right in the guts.

Text: Magnus af Petersens

Magnus af Petersens

Magnus af Petersens (b. 1966), curator with responsibility for contemporary art and the Moderna Museet collection of film and video material. He started at Moderna Museet in 2002 and curated Moderna Museet c/o Enkehuset (West African portrait photography, 2002), Odd Weeks: Peter Johansson, Moderna Museet c/o the House of Nobility with Henrik Håkansson, and Odd Weeks: The Last Picture (2003), In Focus: Björn Lövin, and Fashination (together with Salka Hallström Bornold, Lars Nittve and Lars Nilsson, 2004). Magnus af Petersens is in charge of the exhibition series The 1st at Moderna, in which he himself curated Miriam Bäckström/Carsten Höller, Typ-O Writing with Style, Su-Mei Tse, Emily Jacir and Janet Cardiff.

In 1997-2002, Magnus af Petersens worked for Riksutställningar – Swedish Touring Exhibitions, where his curatorship included an exhition of Öyvind Fahlström’s prints and multiples, Inferno Paradiso with Alfredo Jaar, and History Now (jointly with Niclas Östlind). Prior to this, he was a curator at Färgfabriken.

He has also worked as a critic for magazines such as Hjärnstorm and was the chairman of the photography festival Xposeptember. He co-edited Moderna Museet’s collection catalogue, The Book (2004) together with Moderna Museet curator Cecilia Widenheim.

After the Paul McCarthy exhibition, Magnus af Petersens will proceed to curate a new hanging of Moderna Museet’s collection of contemporary art. He will also be involved in the touring of the McCarthy exhibition from autumn 2006 to spring 2007.

Magnus af Petersens, curator with responsibility for contemporary art and the Moderna Museet collection of film and video material.