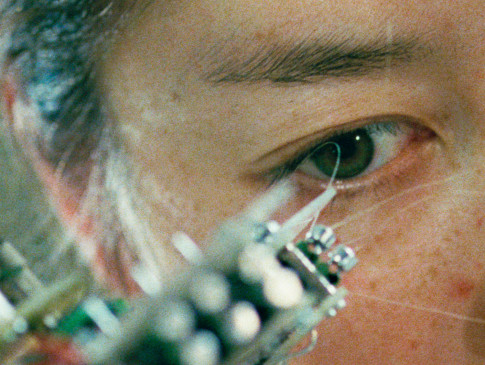

Ryan Trecartin, Trill-ogy Comp, 2009 (Video still)

© and Courtesy the artist and Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

About the artworks

Read about all the featured artworks and artists in the exhibition The New Human:

Adel Abdessemed | Ed Atkins | Robert Boyd | Esra Ersen | Harun Farocki | Kerstin Hamilton | Daria Martin | Santiago Mostyn | Ursula Mayer | Adrian Paci | Tomáš Rafa | Frances Stark | Hito Steyerl | Superflex | Ryan Trecartin.

Ryan Trecartin

Trill-ogy Comp (2013), showing 25 November 2016–5 March 2017

Ryan Trecartin’s hyper-intense video installation Trill-ogy Comp offers a vision of human interaction in an era of information overload, accelerating technical development and global capitalism.

The fairly young individuals populating his feverish universe seem to have mutated through hyper consumption, social media, corporate culture, and reality TV into something beyond human. With high pitched voices, they speak a language saturated with acronyms, internet jargon, and SMS abbreviations, and their pattern of movement seems dominated by various narcissistic poses.

The installation Trill-ogy Comp comprises three videos that are all installed in individually furnished environments. For instance, K-Coreal NC.K (section a) is presented in a completely white corporate environment, furnished with a conference table and replica Eames chairs. The viewer is welcome to take a seat, put on a pair of headphones, and subsequently dive into a story about a Korean multi-national corporation.

In a hyper-intense flood of fragmented images and digital effects, the company’s employees appear, all wearing blonde wigs and having names referring to their employer’s bilateral trade relations, such as “British Korea,” “Armenia Korea,” and “Another Greek Korea.”

Played out in the same flipped-out and flickering universe, Sibling Topics (section a) is projected within a turquoise environment with airplane seating. Here we encounter a woman who has evolved beyond biological reality and is eleven months pregnant. While practicing yoga, she speaks to her yet unborn quadruplets — two days before her own death and twenty-seven years before her children will see this video message from their mother. Then, in a kind of reality-TV format, we get to follow her daughters: Britt, Ceader, Adobe, and Deno, all named after different software programs.

Finally, and placed at the center of the installation, Popular S.ky (section isch) is shown in a pinkish brown environment with a picnic table. Characters from the other two videos here submerge in ‘fevered and shadowy projections of a mind that is being played with.’

While it risks throwing the viewer into an audiovisual state of shock, Trill-ogy Comp poses important questions about what it really means to be human in an era of global capitalism and digitization.

Ryan Tricartin was born in 1981 in USA. He lives and works in Los Angeles.

Ursula Mayer

Gonda (2012), showing 1–2 October 2016

Atom Spirit (2016), showing 30 September 2016–5 March 2017

In Ursula Mayer’s recent films, language and categories such as gender and nature are in the process of dissolving. Different materials seem to be coming together to form new compounds, and we get the feeling that man as a species is on the verge of either disappearing or taking on a new form.

Her new film, Atom Spirit, explores the relationship between advanced technology and nature in the post-human age—that is, in the era some say will follow the anthropocentric time we are currently living through. The film is set in the West Indies, in a landscape that evokes the Garden of Eden and in which visitors uninhibitedly indulge their desires.

The film’s protagonist, a biology researcher, is played by the actor Valentijn de Hingh. She is working on a genome project with the ambition to gather and cryogenically freeze DNA from all forms of life. She also works on the side as an actor in a motion capture studio that animates species threatened with extinction. When she discovers that she is a descendent of an ancient Caribbean civilization that was wiped out by the British colonization, she begins to imagine a cyborg future in which her ancestors’ understanding of the nature of the world could come together with the digital and technical breakthroughs of her own era.

During the last weekend of September, Ursula Mayer’s film Gonda will also be screened. This film is based on the fairly unknown drama Ideal from 1934, written by the Russian-American author and philosopher Ayn Rand (1905–1982). Rand inspired leaders such as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Many of her ideas are manifested in today’s globalised capitalism, a system plagued by recurrent financial crises, and which can be blamed for disastrous environmental consequences – but outside which it has become difficult to even imagine our existence.

Ursula Mayer was born in Ried im Innkreis, Austria in 1970 and lives and works in London, England, as well as in Trinidad and Tobago.

Adrian Paci

The Column (2013), showing 30 September 2016–5 March 2017

In The Column, several stories are told simultaneously. We follow the path of a block of marble from a quarry in China towards Europe. At the same time, we see how the raw block is transformed into a Corinthian column, a symbol of Antiquity and its legacy in western culture. On board the ship are stonemasons who; working in conditions that are both fantastical and inhumane, sculpt the column while crossing the sea.

The focus of The Column, as so often in Adrian Paci’s work, is the living conditions faced by people today—conditions determined by a global economy, a brave new world of freedom of movement. However, none of the people we see are the films protagonists; instead it is the stone—the column—that drives the action forward. The masons follow, as a consequence of the stone, man’s freedom of movement conditioned by the freedom of movement of goods.

Adrian Paci has spoken about how he heard of the possibility of having stonework executed en route over the sea from a friend who was a restorer. It is worth noting that what we see in the film is a real phenomenon and not purely a product of the artist’s imagination. The Column was co-produced by Röda Sten Konsthall in Gothenburg and shown for the first time at Jeu de Paume in Paris, alongside the finished column.

Adrian Paci was born in 1969 in Skhoder, Albania and lives and works in Skhoder and in Milan, Italy.

Esra Ersen

If You Could Speak Swedish… (2001), showing 9 September 2016–5 March 2017

In 2001, when the Turkish artist Esra Ersen was temporarily living in Stockholm, she signed up for a course in Swedish for immigrants and refugees. Once there, she asked each of her classmates to answer the following question in their own native language: “What would you like to say if you could speak Swedish?”

The film presents us with her classmates as they try to read their answers translated into Swedish, a language that is still foreign to them. The content of their texts spans from existential reflections to personal and political statements. The new language forms a kind of tightly woven net that is clearly difficult to get through. The students stumble over the words, backtrack and try again. In the background the teacher’s voice is heard, correcting pronunciation and accentuation.

Large numbers of people are today leaving their home countries by choice or by necessity in the hope of creating a better life in a new place. If You Could Speak Swedish makes these migrants’ often vulnerable situation physically tangible. The work captures how an individual’s identity must be continually re-conquered in the confrontation with a new language and a new culture.

Esra Ersen was born in Ankara, Turkey, in 1970 and lives and works in Berlin, Germany.

Adel Abdessemed

God is Design (2005), showing 21 May 2016–5 March 2017

In the animation God is Design, graphic black lines form a flowing ornamental movement against a white background. Patterns and structures arise out of the lines, only to dissolve the next moment and regroup into new patterns. The jerky, pulsating motion corresponds to the hallucinatory music by the Brazilian composer Silvia Ocougne.

The animation is based on drawings depicting symbols found in Christianity, Islam and Judaism, three monotheist religions. These symbols are interspersed with schematic drawings of human cells.

Adel Abdessemed’s art is often political, with links to life in exile. Over the years, he has been forced to leave societies where he has felt his freedom becoming curtailed. Early in his life, in 1994, he decided to emigrate from Algeria due to the unsettled situation there.

A few years before creating God is Design, Abdessemed left New York in the aftermath of 9/11, 2001. The mood in the USA was one of suspicion against Muslims and people with a Middle Eastern background. Concepts of liberation, struggle and civil action are central to Abdessemed’s oeuvre, along with the fight against all forms of laws and moral codes that serve only to restrict our lives.

Adel Abdessemed was born in Constantine, Algeria in 1971 and now lives and works in London, England.

Ed Atkins

Even Pricks (2013), showing 21 May 2016–5 March 2017

Death Mask II: The Scent (2010), showing 21–22 May 2016

Ed Atkins’s videos have been described as metaphysical poetry expressed in a digital language. He is fascinated with high-definition video and surround sound audio for their paradoxical ability to simultaneously create both surface and body—to produce images that are uncannily realistic and at the same time completely dead.

In the video Even Pricks, the manuscript is presented as rows of text in video-game environments and as hyper-designed title sequences for big-budget movies that are never released. A talking chimpanzee seems to gaze in our direction, straight through the screen that separates our realities. But it doesn’t seem to be able to see us; instead it appears to be using the screen as a mirror.

Another character is played by a human-like hand giving the “thumbs up”—a sign for “liking” something that has come to pervade everyday life for the billions of people who are active on social media. It is a symbol that goes far back in time, associated for example with the judgement over life and death in the spectacle of Roman gladiators, a historical example of violence as popular entertainment.

Atkins has expressed an averse fascination with how audio-visual effects in advertising and the movie industry, as well as the set structures and functions of social media, influence our way of being, thinking, and interacting. Even Pricks portrays a hyper realistic but lifeless world infused with artificial effects and a constant succession of new lavish promises.

Within the framework of THE NEW HUMAN, Atkins’ earlier work Death Mask II: The Scent will offer yet another suggestive meditation on life, death and transience – exploring the transformation from living organism to image and representation.

Ed Atkins was born in Oxford, England 1982 and lives and works in London, England.

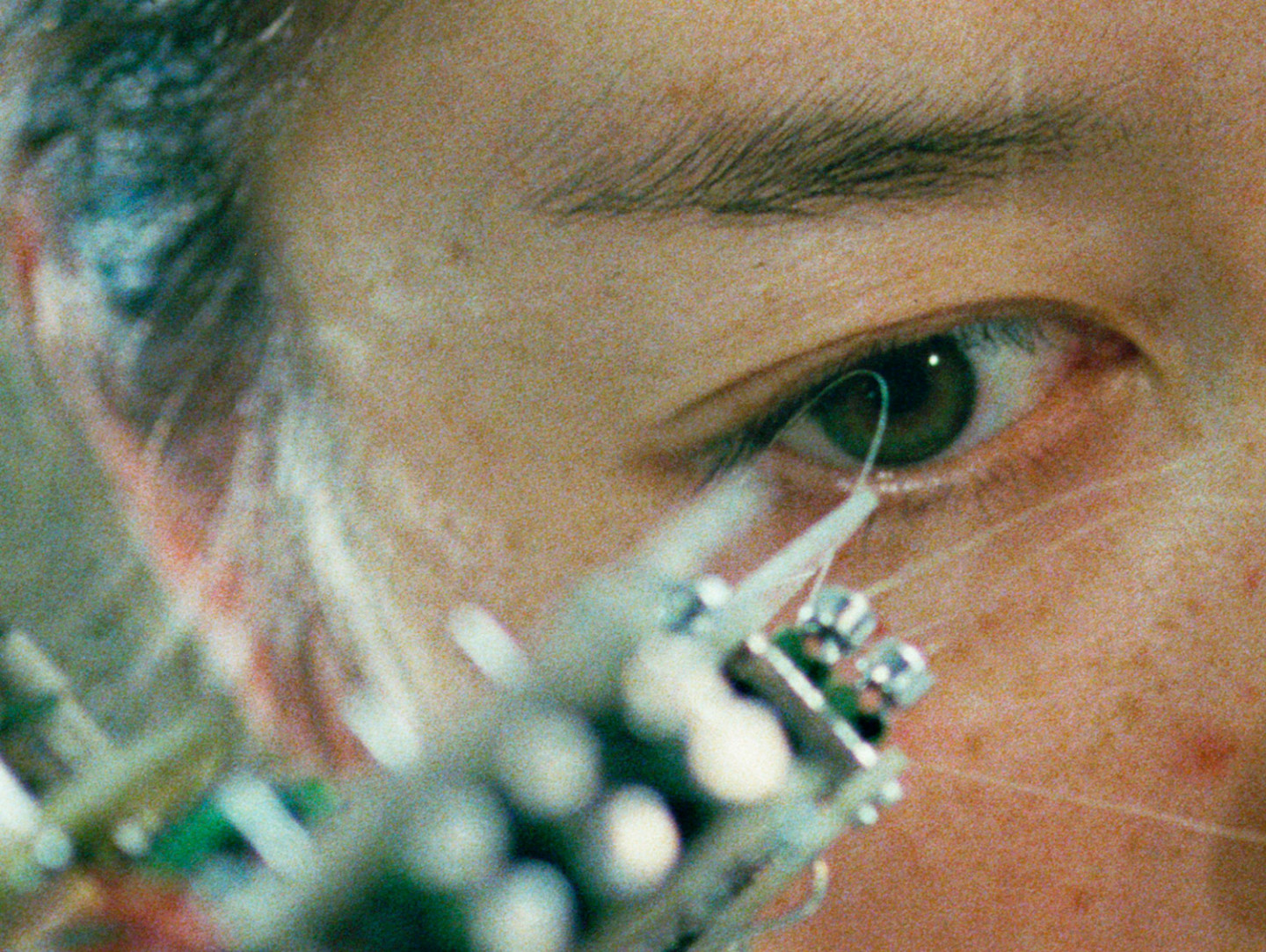

Daria Martin

Soft Materials (2004), showing 21 May 2016–3 March 2017

What associations does the word robot bring to mind? A machine that is trying to imitate a person? Something reminiscent of humans, or something trying to figure us out?

In Soft Materials, two professional dancers interact with robots that look nothing like the stuff of science fiction. These robots are not pre-programmed with computer brains. Instead they are constructed to explore and learn through their physical bodies. As a consequence, their interaction with the environment is quite similar to that of human or animal infants.

Soft Materials was filmed in the Artificial Intelligence Lab at the University of Zurich, where scientists research embodied artificial intelligence. Embodiment indicates an idea or feeling made tangible, and so embodied artificial intelligence attempts to recreate, not only human thinking, but also human locomotion and perception. By reproducing in robots what is not fully understood in humans, scientists attempt to gain a better understanding of the human condition, while at the same time developing machines that behave more and more like us.

In Soft Materials, the humans and robots seem to be exploring together, curiously observing and interacting with one another. An eerie choreography unfolds in which it is hard to detect who is mirroring whom. We see hands that touch and discover, steps of different intensity, eyelashes and metallic feelers that touch each other, and in certain moments an unexpected intimacy without words. A rhythm similar to a heartbeat is present throughout the film, ultimately revealing itself as the sound of hands typing on a computer keyboard.

Daria Martin was born in San Francisco, United States in 1973 and lives and works in London, England.

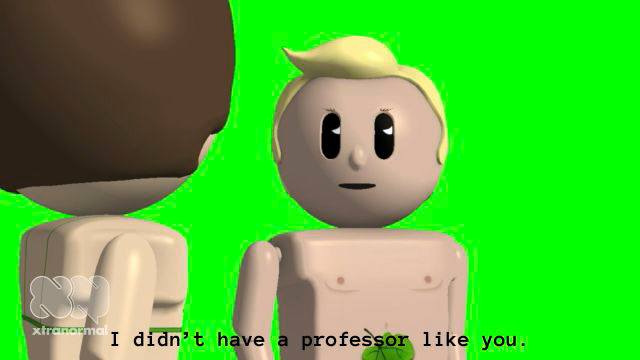

Frances Stark

My Best Thing (2011), showing 21 May 2016–3 March 2017

Throughout the 25 years of her career, Los Angeles-based artist Frances Stark has worked in a wide range of techniques, from charcoal, painting and collage, to mass media such as iPhone photography and PowerPoint presentations. She is also a writer. The oscillation between these two disciplines often manifests itself in works of art that demonstrate how text, language and image interact to produce what we call “meaning”.

Writing is also the starting point for My Best Thing, a feature-length animation. Using a keyboard and a webcam in her studio, the artist meets young Italian men on a video chat. Their chat leads to virtual sex, but also to discussions about the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, the director Federico Fellini, and film.

The work is intimate and revealing, even though we never get to see Frances Stark, nor her dates. The story has been cast in a shape that is both banal and user-friendly and this easy access aesthetic is an important part of the work.

My Best Thing was produced using the Xtranormal website, whose logo is visible in the lower left-hand corner of the image. Thus, Stark joins the millions of people who have made videos using Xtranormal. She turns the chatting individuals into stylised, angular characters with fig leaves covering their private parts.

The voices we hear are computer-generated. A monochrome green background has been chosen by the artist, suggesting the “green screens” used when filming people or objects before replacing the green colour with footage of other settings. Here, the background emphasises the fact that the romantic encounters take place in a space that is hard to pinpoint; some kind of nowhere-land.

The anaemic characters and the monochrome background also prompt us as viewers to actively infuse the drama with life by projecting our own feelings on what we see. In an era where technological development has made it possible to exist in multiple mental and virtual spaces and to engage in diverse kinds of relationships, My Best Thing raises questions relating to desire – who are we, and who do we want to be in the eyes of others?

Frances Stark was born in Huntington Beach, California in 1967 and now lives and works in Los Angeles, California.

Hito Steyerl

How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2014), showing 21 May 2016–3 March 2017

This video is a tutorial—or rather a parody of the many how-to tutorials available online. This particular tutorial guides us in how not to be seen in a digitalised world with cameras on every corner and on every individual. A male computer voice reads the instructions, and the artist herself demonstrates some of the techniques. The gestures Hito Steyerl uses are the same familiar hand gestures used with smart phones or tablets. In a world flooded with images asserting people’s existence, Steyerl offers lessons in how not to be seen.

A female computer voice informs the viewer: “Today most important things want to remain invisible: love is invisible. War is invisible. Capital is invisible.” Another voice gives instructions about how to hide and escape the camera, by camouflaging into a picture, shrinking to the size of a single pixel, or disappearing as an enemy of the state.

While some might struggle for the right to be invisible, people and information can also be made to disappear through violent force. This video tackles issues of surveillance, hyper visibility, and disappearance on many different levels. It was filmed in the California desert where, in the 1950s and 60s, resolution targets were painted on the ground to calibrate aerial photography. The painted targets were also used to test the cameras that become the ancestors of today’s drones.

Hito Steyerl was born in 1966 in Munich, Germany. She lives and works in Berlin.

Superflex

The Financial Crisis (Sessions I-IV) 2009, showing 21 May 2016–3 March 2017

SUPERFLEX is a Danish artists’ group. They believe that the main purpose of art is to challenge viewers with artists’ unique perspectives on society. SUPERFLEX calls their works tools since they want to engage viewers with direct participation and involvement. This also implies that artworks have the potential to ignite real change in the world.

In The Financial Crisis, SUPERFLEX invites you to experience a financial crisis on both a mental and physical level by means of hypnosis. A hypnotist guides you through a full experience of capitalism by first taking you to a small town’s market, then allowing you to experience what it’s like to be a billionaire, then throwing you back into being miserably poor, and in the concluding stage offering you a possibility to free yourself from the capitalist system entirely.

A sense of physicality is added as the hypnotist instructs you to experience impotence in different parts of your body, as well as to imagine that you are moving the “invisible hand.” The “invisible hand” is a metaphor for a highly influential economic principle defined by the eighteenth-century economist Adam Smith. It’s a kind of self-regulating mechanism, a natural force if you like, thought to tame capitalism from within.

As the hypnotic session progresses and everything collapses around the person being hypnotised, deep angst is evoked. Towards the end, however, we can observe what has taken place from a distance and chose to leave that which has caused despair.

SUPERFLEX is an artists’ group founded in 1993 by Jakob Fenger (born 1968), Rasmus Nielsen (born 1969) and Bjørnstjerne Christiansen (born 1969). They all live and work in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Harun Farocki

Serious Games III: Immersion (2009), showing 21 May 2016–13 November 2016

Serious Games is an exploration into digitalised warfare. What happens when the enemy is transformed into a computer-generated avatar? How is the emphatic capability in a person influenced by the task of bombing a target from a safe, air-conditioned office on the other side of the globe?

In the video and computer gaming industry, war is a common subject. Computerbased war games have their origin in the military and were first developed for training purposes. War gaming later evolved into a hobby but is still used as a military work tool. The military uses video games for three purposes: recruiting, training, and, most recently, as therapy.

Virtual Iraq is the name of a virtual reality platform specifically developed to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. Within a method known as immersion therapy, this platform is used to help soldiers overcoming memories by evoking them. By virtually recreating specific traumatic situations in a controlled environment, therapists aim to help soldiers familiarise themselves with the nature of their traumatic experiences. This, we could say, is a simulation of memories. Simulation technology was developed by the military, then it was taken over by the gaming industry, and now it is going back to its initial creators.

But can the distinctive aesthetics of video games really prepare people for the actual war experience, and ultimately heal its scars? Recruiting, training, therapy: virtual reality is the beginning and the end of war. But how virtual can war really be? Serious Games III: Immersion was filmed at a workshop near Seattle (USA) where therapists were given instructions in how to use Virtual Iraq.

Harun Farocki was born in 1944 as Harun El Usman Faroqhi in the Czech Republic. He died in Germany in 2014.

Santiago Mostyn

Delay (2014), musik/music by SW (S. Jablonski and W. Rickman), showing 21 May 2016–13 November 2016

“How to come to terms—not only as an artist but as an ‘artist of colour’—with my place in this society that I now call home? This is the question that burdens me. More so than the recurring inquiry from new acquaintances— ’How long will you stay in Sweden?’—which veils their assumption that I should one day leave. And more so than the question of how to respond to the occasional late-night Nazi salute flourished in my direction or the myriad other slights and offenses that niggle at one every day. The first response, of course, is to push back. The bluntness of a violent reaction feels right in the moment, feels like it will get something across. But how provocative can it be, in the end, to react exactly as all these blank faces expect you to? Why let them put me in that box? The connection that I simultaneously spurn and desire, this nebulous ‘belonging,’ is more nuanced than anything a clenched fist can provide.”

The quotation above, written by Santiago Mostyn, refers to his video, Delay. The work presents us with a young man – the artist himself – as he moves and dances through the streets of Stockholm. On several occasions he slows down and interacts with strangers he encounters, all of whom are white men dressed for a night out. The footage has a dreamlike quality and the film’s protagonist appears in moments like a messiah, attempting to bring tenderness to a society increasingly marked by social conflict. But however gently given, the man’s transgressive touch is a double-edged sword, posing a threat to these privileged strangers who don’t know how to respond and whose range of baffled reactions are recorded for us to observe.

Santiago Mostyn was born in San Francisco in 1981 and lives and works in Stockholm.

Tomáš Rafa

New Nationalisms in The Heart of Europe (2009–), showing 21 May 2016–4 September 2016

Walls of Sports (2012–), screening 21 May 2016–4 September 2016

Refugees on Their Way to Western Europe (2015–), screening 21 May 2016–13 November 2016

Since 2009, Tomáš Rafa has been documenting Europe’s emerging nationalism and neo-fascism. He has also monitored and documented how Europe has handled the refugee crisis since 2015. The distance we try to maintain to the flow of news images tends to dissolve when we are faced with Rafa’s portrayals.

At close range, they confront us with raging mobs who spew out their hatred against immigrants, refugees and other minorities. His video reports show the panic and despair of refugees at various European frontiers, people fainting from exhaustion, terrified children and parents pressed against barbed wire fences marking national borders.

As if to fend off this brutal reality, Rafa also engages in a form of political art activism – with both vitalising and therapeutic ambitions. The most acknowledged of these projects is Walls of Sports. It was carried out in several Slovakian communities where local government authorities have built high cement walls to keep the Roma population away from the other citizens.

In a collaboration between the artist, inhabitants and volunteers, the segregating walls were transformed by monumental murals in a way that made them visible to the world and at the same time slightly less brutal for those who have to live close by. Within the framework of the same project, Rafa also organised workshops for children, as well as an art therapy project where a Roma family used dance, drawing and painting to process traumatic memories from when their children were tortured by the Slovakian police force.

THE NEW HUMAN features material from both New Nationalisms in The Heart of Europe, Walls of Sports, and Refugees on Their Way to Western Europe. During the time of the exhibition, Tomáš Rafa will also give a talk at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, focusing on the refugee crisis.

Tomáš Rafa was born in 1979 in Žilina, Slovakia. His videos and photographs are also available online at New Nationalism.

Robert Boyd

Xanadu (2006), showing 21 May 2016–25 September 2016

In the video installation Xanadu, Robert Boyd combines a euphoric disco atmosphere with terrifying glimpses into man’s collective brutality. The work is built up of hundreds of hours of archival film, that in an apocalyptic flood of images confronts us with the global phenomenon of doomsday cults, religious fanaticism, and political extremism.

The overwhelming and deeply disturbing material is presented as extended music videos, shown in a space similar to a dance club. The facile pop song Xanadu is playing on an infinite loop, and rotating above our heads is a glittering disco ball.

The title Xanadu historically refers to the magnificent city founded in the fourteenth century as a summer residence for the Mongolian emperor Kublai Khan, and which achieved widespread fame through Marco Polo’s descriptions of its mythical splendour. It also inspired the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge to write the poem “Kubla Khan”, the publication of which made Xanadu more or less synonymous with a vulgar and un-Christian version of paradise.

Boyd’s Xanadu comprises four parts: Patriot Act, Heaven’s Little Helper, Judgment Day, and Exit Strategy. Viewers are confronted with doomsday prophets and their followers, global political leaders, and various examples of violence and extremism from around the world. Taken together, the sampled fragments form a chronicle of the years between the Second World War and the war in Iraq at the beginning of the new millennium.

The piece culminates in a sequence in which President George W. Bush addresses the American people following the attacks on September 11, 2001, declaring the end of a “feel-good era” and the beginning of a new time. This time, Boyd seems to suggests, is our own Xanadu—a conglomeration of fears, paranoia, and prejudices mixed with a media saturated and spectacle-besotted consumer culture.

Robert Boyd was born in 1969, and lives and works in New York, USA.

Kerstin Hamilton

Zero Point Energy (2016), showing 21 May 2016–25 September 2016

Zero Point Energy is set inside a cleanroom – a laboratory for research at the atomic level. The materials that are studied and created within nanoscience exist in a world beyond our perception, one that we can neither see nor feel. A recurring theme in nanoscience is the notion of breaking new ground; of embarking on a journey into the unknown. In many ways it is a reflection of space exploration; a miniature space full of undiscovered worlds.

In the film we encounter humans and machines, two essential actors in the nano research. The scientists are covered in garments that separate them from the nanometre-sized protagonists, their full-body coveralls and the white and yellow lighting give the room a distinctive quality. Inside this room a new humanity is taking form and established boundaries are dissolved.

Nanotechnology presents the prospect of a human existence – promising yet perilous – permeated by technological constructions. It is a vision of man both as creator of technology and created by technology.

The title, Zero Point Energy, refers to the energy of the ground state of any quantum mechanical system. In the film this term is used speculatively, suggesting an imagined ground state of the cleanroom. Inside the cleanroom, movements and behaviours are strictly regulated to prevent humans from influencing the sensitive processes in undesirable ways.

In a choreography where researchers become dancers, this control over the individual in the service of science is both accentuated and challenged. The systematic structure of the ballet emphasises controlled patterns of movement but also introduces disruptions and energy that moves the cleanroom from its ground state and challenges it’s inherent choreography.

Zero Point Energy is part of the project Nanosocieties, a collaboration between artist Kerstin Hamilton and the nanoscience researcher Jonas Hannestad. The choreography is developed by Anna Asplind and the sound composed by Lena Nyberg and Emma Ringqvist.

Kerstin Hamilton was born in Karlstad, Sweden 1978 and lives and works in Gothenburg, Sweden.