William Kentridge - Moderna Museet Fotograf: Juan L. Sánchez

Black Box/Chambre Noire

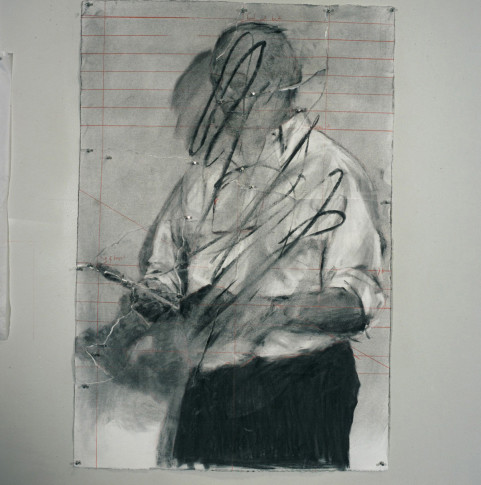

The piece comprises a mechanised theatre with two projections, six figures and some 50 drawings. The duration of the show is 23 minutes, followed by a period of twelve minutes in which the space is illuminated, giving the audience the chance to see the rest of the components of the installation. This allows us to work through the show and re- experience the drawings that were used for the animations. We get closer, and can read and examine the details. As with the constant metamorphoses in his animations, it is a device for Kentridge to incorporate the production process in the work and to openly account for his method of working. It begins to dawn on us that the depiction also points to how we as receivers create meaning of what we see. To experience and understand the world is also a long and painful process where nothing is static. In addition to the fact that the title alludes to the black room of a theatre or a cinema and the black box of an aeroplane, it also refers to the inside of a camera, the apparatus that translates reality to image and thus creates history. Out of the thousands of potential images that flow through this apparatus one is chosen and fixed – a somewhat arbitrary truth.

The show itself begins with a megaphone stepping onto the stage like a presenter, announcing a “Trauerarbeit” [an act of mourning]. This was a term that Sigmund Freud invented to describe an essential and never-ending process undertaken to avoid the denial of, say, a great loss. The most important point of departure of the work, the catastrophe and that which is alluded to in the act of mourning, is the forgotten massacre of the Herero people in German South-West Africa (present day Namibia) in 1904-1907. In 1885, South-West Africa became a German protectorate, after which settlers began to encroach upon and exploit the land of the African indigenous people. Out of frustration, the Herero people revolted in 1904 against the colonisers who hit back against the uprising with disproportionate force. Despite protests, the brutality did not cease until 1905, by which time 75% of the Herero people had been annihilated. This atrocity is often referred to as the first genocide of the previous century.

However, the show is not a linear narrative but rather conveys itself through our senses. It is at times beautiful, violent, horrible and sad. Just as in 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, Kentridge refers to other artists and thinkers in the formation of the piece. During the preparations for the production of Black Box/Chambre Noire, he worked on a production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute (1791), a work that in many respects touches upon the same colonial questions that Kentridge reflects on. In Mozart’s opera, Sarastro (the reasonable sovereign who symbolises light and rules with wisdom) kidnaps the Queen of the Night’s daughter, with the intention of liberating her from irrationality and ignorance, in the same way as Europe occupied Africa with the excuse of enlightening “the dark continent”. Kentridge also refers to Plato’s metaphors of light and shadow; notably the cave parable from the dialogue The Republic (374 B.C.) where it is suggested that we have a moral responsibility to liberate the prisoners of ignorance and drive them out into the light towards the true knowledge of the world.

The design of the miniature theatre hence originates from the model that Kentridge worked on for the production of The Magic Flute and large parts of Philip Miller’s soundtrack is referring back to the music from the opera. The projection above our heads and the light that creates the moving images remind us of Plato’s description of the light that streams into the cave. But where both Mozart’s and Plato’s positive attitude towards the enlightenment as a project characterises their work, one could say that Kentridge’s work examines and reflects its flipside: the shadows cast over the world by the light of knowledge. The truth Plato wrote about, does it even exist? What has history taught us? Despite taking its point of departure in central questions from the colonial history, Black Box/Chambre Noire raises essential questions in the world right now.