Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg, One Need Not Be a House, The Brain Has Corridors, 2018 © Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg / Bildupphovsrätt 2018

Across the Stage and Into the Trees: Place and Memory in the Work of Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg

Text: Lena Essling

So rich is joy that it thirsts for woe, for hell,

for shame, for the lame, for the world …

O happiness! O pain! Oh break, heart! …

Joy wants the eternity of all things, wants deep, deep, deep eternity!

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1)

There is an element of seduction when encountering Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg’s work—striking and immediate, it attracts the viewer like a moth drawn to an open flame, straight into its colorful worlds accompanied by hypnotic music. Picture Fragonard’s Rococo fantasy ”The Swing” (2) filtered via pop art’s tongue-in-cheek attitude and with a whiff of decadent club culture on acid. Their playfully told fables are both humorous and dark and incapacitate any moral laws of gravity. Feverish daydreams or fragments of repressed memories are enacted in dense scenes from the borderlands between innocence and shame. Without knowing exactly how, we have lowered our guard and left behind our laid-back and distanced mode of watching, instead being swept up in a maelstrom that proves difficult to navigate. Soon, the tension heightens, until our flickering gaze no longer wants to see where we’re heading.

Already early on in the preparations for this exhibition the artists described their feelings about it as an internal journey through chaos and confusion, or “an ego’s attempt at finding a way out of itself.” The odyssey goes through dark underworlds, then up into light and air, only to turn back down to the shadows—through wallpapered rooms and thorny terrain, winding musical loops and wormholes in time. Dante’s journey through the circles of hell, Hunter S. Thompson’s wild road trips, or Virginia Woolf’s ”Orlando”—the dramaturgy of journey is familiar and usually leads through shadows, past eternally forsaken demons and toward greater clarity.(3) Here, however, it is not honor, kicks, or a higher power that moves the events forward, but a quest for a fundamental core within us, a flaming inner blaze. “But who are you then, O my soul?”(4)

The Forest, the Cave, the Stage

Certain archetypal surroundings recur in Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg’s work and provide a topological map of the exhibition: the dark forest, the mysterious cave, the intimate chamber, the illuminated stage. Demarcated places where painful or comical scenes are played out between figures that are often close to each other, sometimes even literally attached at the hip.

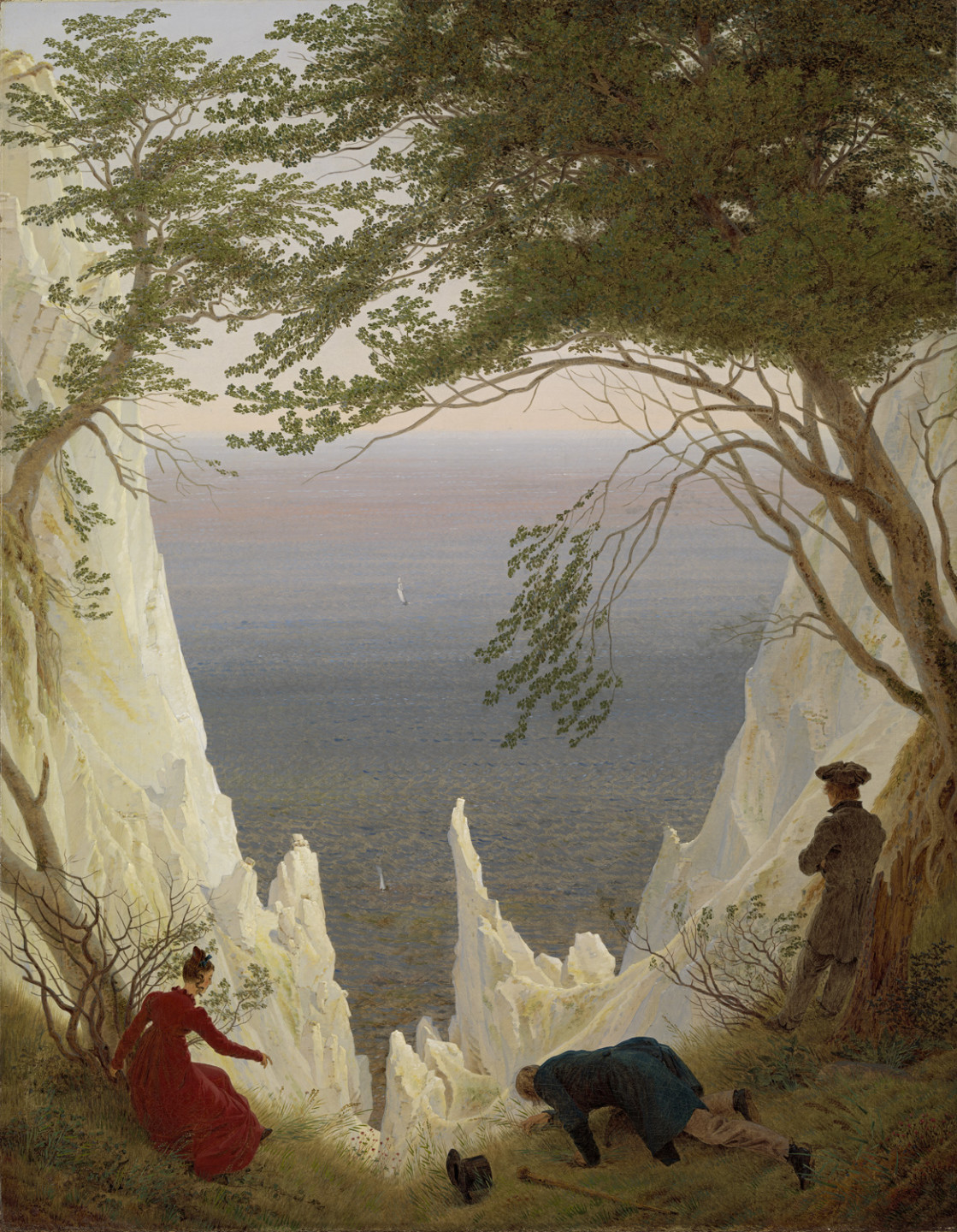

Caspar David Friedrich’s painting ”Chalk Cliffs on Rügen” depicts three figures standing on the rim of a dramatic precipice, facing the sea: the aging artist himself on all fours before the chasm, groping for his hat; his younger wife and their travel companion in contemplation of the open horizon, the fantastic light. Friedrich’s painting is often interpreted as a triumphal homage to the Enlightenment and magnificent landscapes. However, as the British cultural historian Jonathan Meades has pointed out, there is another way of looking at the motif in which the people are in fact turning away from the forest rather than toward the sea: “What Friedrich’s painting does not reveal is the forest behind him, behind the figures staring transfixedly at the sea and at a limitless world. … For Friedrich, as for the Brothers Grimm, forests were places of real and metaphorical darkness which mankind had ceased to dwell in and worship in; which mankind had escaped from, but which still exerted a morbid attraction.”(5) To this day, anyone who wants to hike out to the chalk cliffs in the painting has to go through dense forest to reach the view and the light. A trip that has Meades overcome with primal fear and that seems to make an atavistic memory surface—a primitive recollection that we have shared since time immemorial.

The notion of nature as a temple and a place of contemplation where he who seeks can find strength and light is of course also found in the writings of Henry David Thoreau and many others. The film ”Ewiger Wald” (1936),(6) which portrays the German primal forest as both a habitat and a symbol of the “Volk,” is an example of how the idea of nature as spiritual has been manipulated for the purposes of propaganda. A forest that has historically provided shelter and sustenance, only to later be ravished by (partially dark-skinned) French troops, suffer in the Weimar Republic and, finally, be restored by National Socialism. Perhaps it is precisely because we experience our relationship with the forest as both symbiotic and conflict-ridden that it continues to be the site of dark imaginings—from ancient fairy tales and legends to Sam Raimi’s ”Evil Dead” (1981) or Lars von Trier’s ”Antichrist” (2009).

Caves and chambers, also recurrent environments for Djurberg and Berg, also have ambivalent connotations: a stuffy terrifying cavity, but also a remote, holy place that people have sought out to leave codes for an uncertain future or isolate themselves in order to achieve higher knowledge. According to René Guénon, the French proponent of metaphysics and symbolism, the cave and the heart have throughout history been recurrent symbols of “spiritual centers.” Both the cave and the forest are described by C. G. Jung as triggers for the archaic memory that Meades became aware of during his hike on Rügen, and that we have never rid ourselves of. Jung claims that the past precedes us—it leads us forwards, it is always already there, and it can never disappear. Like archaic symbols of what is most original, these places evoke the breathtaking insight of a timeless, eternal Now.(7)

In Djurberg and Berg’s work, the forest glade is the scene of twisted fairy-tale scenarios, like in ”Dark Side of the Moon” (2017), where the interest of the figures revolves around a hut in the forest, a mystical Black Lodge which only certain people may enter. Or for macabre metamorphoses, like in ”Turn into Me” (2008), where a female figure falls dead to the ground and becomes a nest for the small wild animals of the forest; a dancing cadaver as vibrant as the horse’s head in Volker Schlöndorff’s adaptation of ”The Tin Drum” (1979). But in Djurberg’s animation and with Berg’s music, the depiction has dark humor and a certainty in the indomitability of life in the shadow of death, completely and essentially different from Günther Grass’s disturbing portrayal of the escalating lunacy of 1930s Europe. A crass and unsentimental restitution of humans and animals in nature, as scrutinized by Patricia MacCormack in her catalogue essay “Joy is the Core of Horror”, (pp. 115–126) and that can already be found in one of Djurberg’s very first films: in the oil pastel animation ”My Name is Mud” (2003) the clay initially bubbles up in the shadowy glade to a veritable, Old-Testament wave that sweeps over the landscape and takes with it everything that is in its way—even the young bovine that touchingly begs for its life.

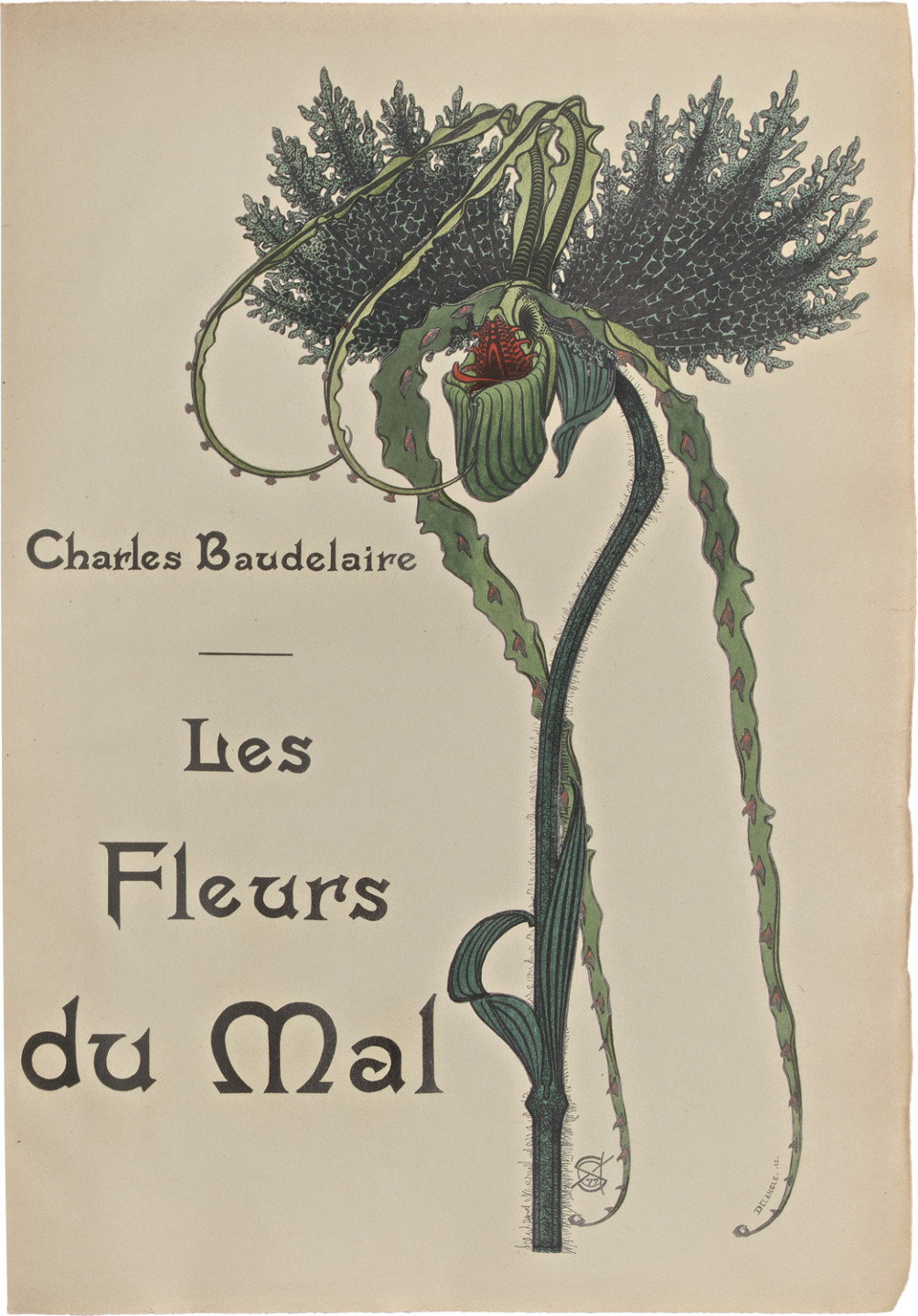

In the work of Djurberg and Berg the forest finds its way outside the frame of the film and into the space in ”The Experiment” (2008), a work that was created for the Venice Biennale in 2009. It was installed in the lower gallery of the Central Pavilion where Marina Abramovic´ had scrubbed animal bones twelve years before in her performance ”Balkan Baroque” (1997). But what the audience descended into this time was not a butchery and a dirge but a murky, overgrown garden with darkly sweet flowers and strange beings. A potential cruising ground at the heart of the biennale with similarities to Hieronymus Bosch’s baroque dream landscapes, that seemed to promise both pleasure and torment. In ”The Cave”, one of the three films included in the installation, we encounter a startlingly distorted figure, captive in a room that is simultaneously a cell with a washbasin and a mattress and a cave with crystalline stalactites. In ”The Forest” a woman flees through a dense forest trying to escape a male perpetrator. ”Greed” depicts inaccessible power in the form of Church men, a group of potentates that ensnare a naked girl in their robes. “Do what thou wilt,” as Aleister Crowley put it. As in Charles Baudelaire’s poetry collection ”Les Fleurs du Mal” (1857) or de Sade, a beauty in complete absence of mercy or higher ideals is portrayed in this garden of earthly delights, from a time before reason and the Fall. An underworld without rules that sees boredom and convention as the worst sins.

Okay ladies, now let’s get in formation

A recurring and essentially different milieu in the works is the harshly lit stage where figures display themselves and are viewed. There isn’t always a narrative framework; rather, the consequences of a series of choices made by an invisible game master are presented, like in ”New Movements in Fashion” (2006). Figures are lined up in a row and ordered around in an ongoing social game set to the sounds of a light-hearted musical accompaniment. On a back wall, without the illusion of depth or scenery, the commands and acting instructions change constantly: they are deleted, corrected, written over, edited. The background of the stage becomes the interface between the game master, the figures, and the viewer. Similarly, the figures in ”The Parade of Rituals and Stereotypes” (2012) are played out against each other, sometimes violently: judges, fashion victims, upper-class characters, and exploited wretches. Heartless and farcical, both the figures and the director eventually appear to be the victims of their own vain frivolity. A capricious power controls and rules over a group of lost souls in a work that reeks of social satire—or perhaps religious criticism.

At times the clearly accentuated skin color, sex, age, and physique becomes a comical and disturbing play on stereotypes. Why is the woman’s body not only naked but often particularly curvy and sexualized—sometimes an almost pornographic caricature reminiscent of cartoonists as Al Capp or Robert Crumb? The older figures’ emaciated or grotesquely swollen bodies sometimes even become death traps. Like in ”Once Removed on My Mother’s Side” (2008), where the senile, hopelessly repulsive mother almost crushes her stunted daughter and caregiver. What gives one the right to represent a group or person different from oneself? Then again, what else could one do as an artist?

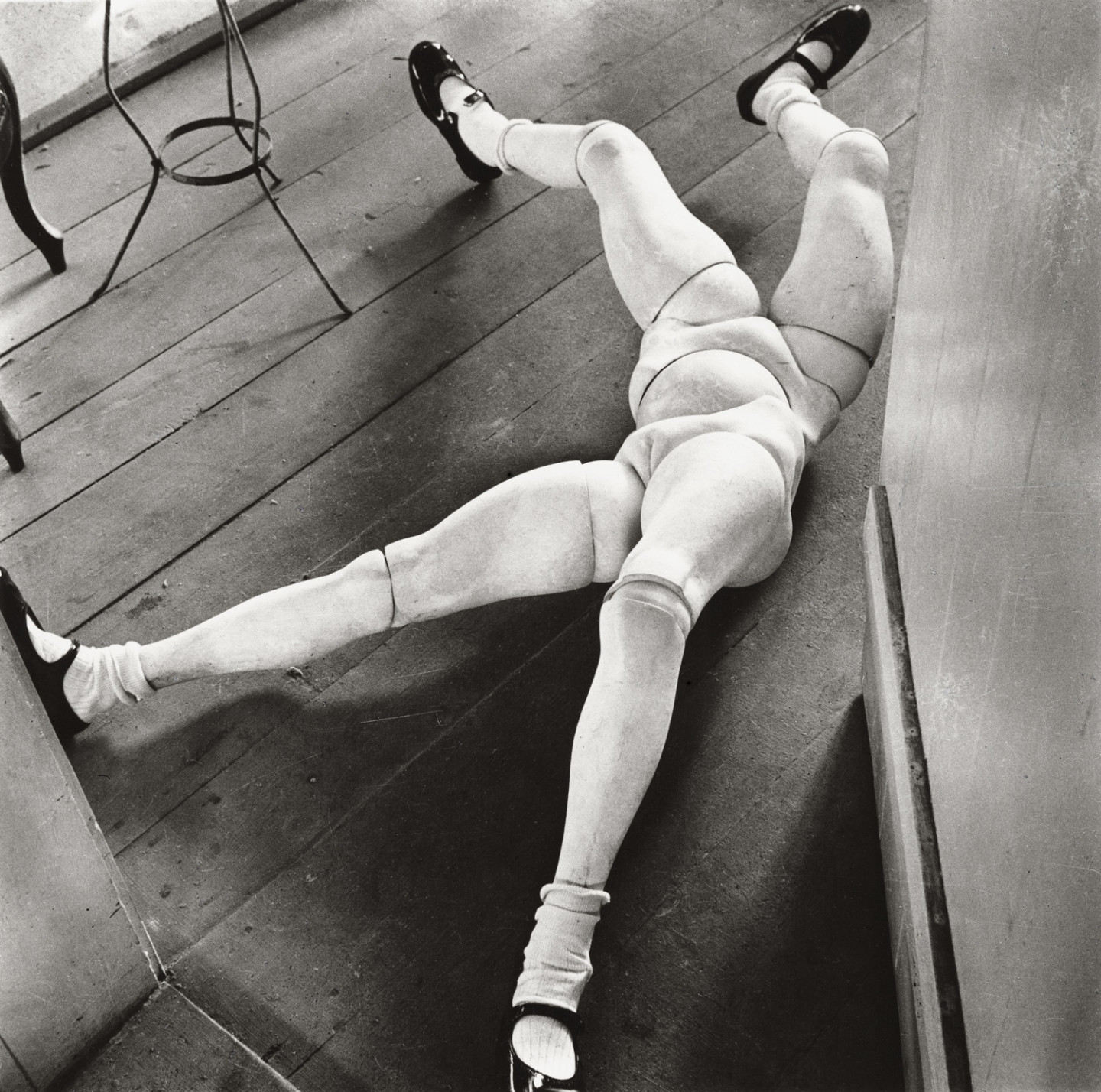

The artist’s indirect presence and persona as omnipotent director or dominatrix has several parallels in theater, film, and performance. There are similarities to the work of Vanessa Beecroft, in which the individual is given a cloned appearance and dissolves in the masses and uniformity. In ”VB16” (1996) the female participants’ nudity is just as much of a disguise—flattened and strangely desexualized in skin-colored nylon underwear: “My way to sublime nudity,” as Beecroft laconically puts it. A classic nude study seen through the 1990s infatuation with low culture. References to chorus lines and catwalks, to femininity as a role and produced identity—even though the militarily uniform group is also subverted into a demonstration of power, like in Beyoncé’s ”Formation” (2016).

The theatrically illuminated birds in the installation ”The Parade” (2011) are also entertainers that naturally fill the space with their wingspans, long necks, and strong colors. There is a certain freedom in the representation of different types and temperaments being translated into animals or beings. One has a sense of being able to hear them, as if walking around on an open street—screeching and the beating of wings, beaks, and claws. The actual sound experience comes from Hans Berg’s musical track to the five films making up the installation, all of which have eggs as their subject—as life, fertility, eternity. The moving image is also full to the brim of color and flowing forms, and it becomes particularly clear here that Djurberg sees herself primarily as a painter, not an animator. She doesn’t chiefly link her films according to topic or characters but by color, and she brings to mind other colorists like a carnivalistic Pipilotti Rist or perhaps the work of Lynda Benglis on the intersection of sculpture, painting, and action.

© Carolee Schneemann/Bildupphovsrätt 2018. Photo: Henrik Gaard/Courtesy of Carolee Schneemann

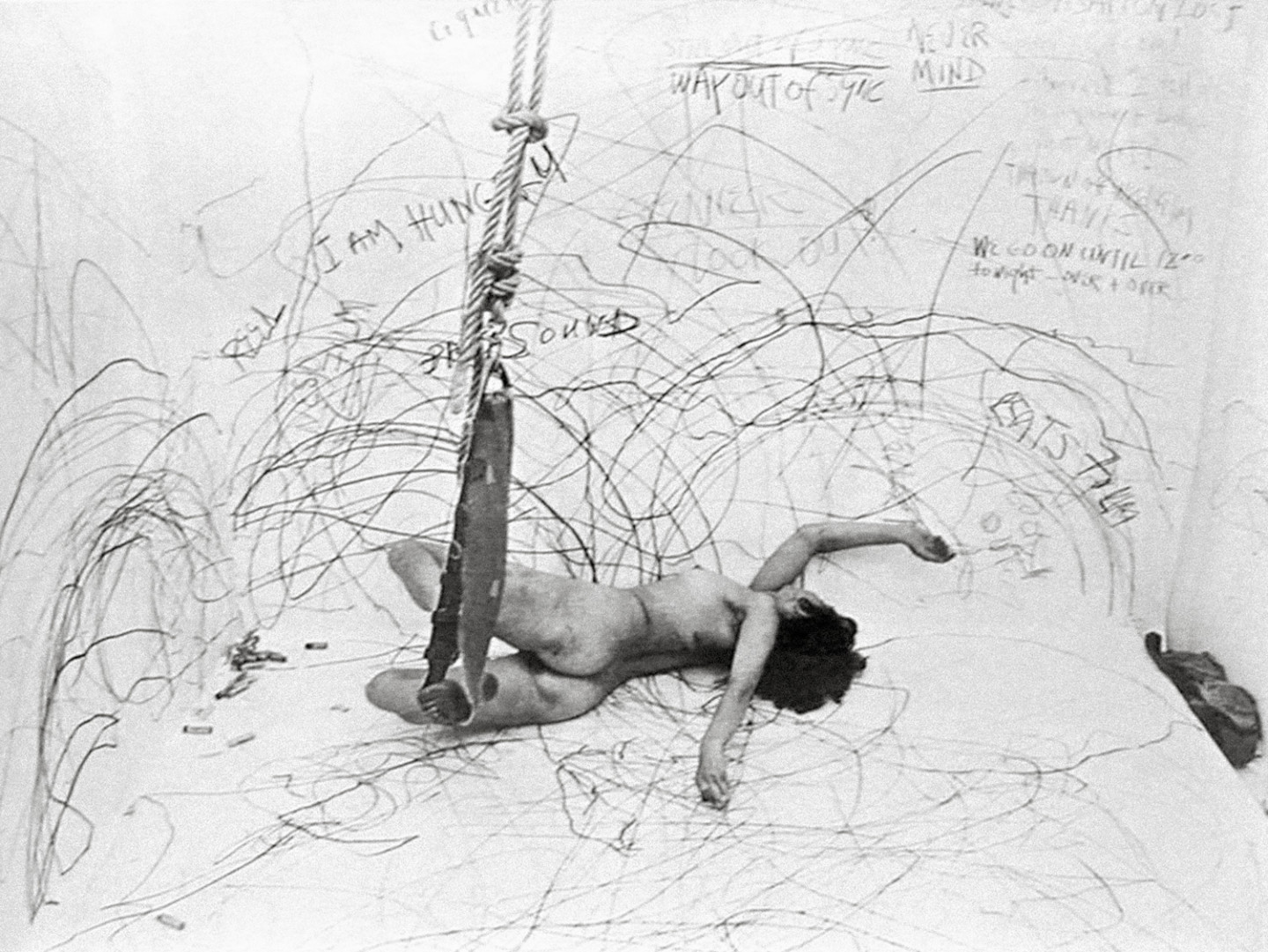

Carolee Schneemann also sees herself more as a painter than a performance or body artist. In ”Up to and Including Her Limits” (1973–76) she tried to expand her work in time and space, inspired by happenings, “and it had nothing to do with self-confession or self-exposure or personal narrative, it really had to do with a painterly sense of an environment as a collage arena.”(8) Suspended in a harness she lets her whole body become the tool of her painterly drawing and writing that haphazardly finds its expression in the given space. A stage where the scribbled words and lines bear traits of both action painting and the automatic writing of the Surrealists, unencumbered by reflection or rational self-censorship. Djurberg’s and Berg’s way of working intuitively in their respective media, without a storyboard or predetermined dramatic curve, keeps the flow unimpeded and the channels open to a subconscious level that allows the work to take over. In a similar way to Schneemann, Djurberg works with broken language in the sets of her films. Her figures and her voiceover often express themselves in a linguistically incorrect manner, in colloquial language and slang, in ways that circumvent our reading of the text as more authoritative than the image and music. Rather than any written dialogue or script in the films, it is Berg’s dense musical compositions that juxtapose or are in a symbiosis with Djurberg’s images, creating new layers of meanings and moods.

The works have several links to performance art and theater, also in the mechanisms of voyeurism that are set in motion when the characters’ excesses and vulnerability become a trial that we are forced to relate to. The disturbing, nervy representation coupled with pitch-black humor and references to pop culture and kitsch bring to mind the American West Coast—Chris Burden, Paul McCarthy, or Mike Kelly. Burden’s work ”Through the Night Softly” (1973) had great significance for Nathalie Djurberg while she was still at art school. In it the artist slithers along a street covered in crushed glass in central Los Angeles with his arms bound behind his back and dressed only in a speedo. Burden performed the work live for a small audience that couldn’t avoid the feelings of pure physical discomfort. He also bought tensecond TV advertising slots where clips from the piece were shown in between ads for soap and car washing services. The work can be read as a satire of the culture in Los Angeles, as well as spitting in the eye of what Burden saw as an increasingly unthinking consumption of all types of images in times when the Vietnam War was the first war to be broadcast on TV. Added to the undisguised pain and vulnerability of an artist at the mercy of his audience is a level of bizarre slapstick—the poetic title (that referred to how the shards glittered on the tarmac like a starry sky), the red bathing suit, the advertising format. There is a specter of this interplay in much of Djurberg and Berg’s work. References to speculative documentary images, ranging from Francisco Goya’s ”The Disasters of War” (1810–1815) to contemporary news reporting also recur. A very early example is ”Dead Boy” (1999), a computer-animated newspaper picture from a war scene somewhere in Latin America in which the halfseated dead body of a boy is quietly smoking a cigarette—an attempt at handling the unbearable images we encounter in the public arena.

Otherness and Ecstacy

In the installation ”The Potato” (2008), the cave can be found as a concrete place in the stage set/sculpture that the public can enter into, the cavities of which house three films noirs. ”It’s the Mother” is a nightmarish bedroom scene where a woman is overpowered by her own children, who one by one push their way into her womb, back to an unborn state. This unnatural scenario culminates in a metamorphosis like that of the dancing cadaver in ”Turn into Me”, when their bodies merge into a multiarmed, multi-eyed being—a monster that helplessly circulates without direction. Undefined identity is also a focus of ”We Are Not Two, We Are One”, where a boy tries to go about daily life while attached at the hip to a wild, outrageous wolf. Their movements around the kitchen are comical and painful, a portrait of our dormant nature that we may live with but are only able to see ourselves. ”The Potato” as a whole, which also includes ”Once Removed on My Mother’s Side”, leaves an impression of thorny, inaccessible undergrowth, a subconscious that we don’t always succeed in mastering but that we have to navigate.

A sense of alienation and otherness in the figures is constantly lurking under the surface in Djurberg and Berg’s work—in the presence of traumas and abuse, compulsive behavior, deviant appearances and personalities. The feeling of neither wanting nor being able to fit into a mold, an attempt at instead drawing up an entirely different map of identity, gender, age. Like when Emil Ferris, artist and writer of the autobiographical graphic novel ”My Favourite Thing Is Monsters”, expresses her distrust of the heteronormative order: “I didn’t ever want to be a woman. I mean, it just did not look like a good thing. Nor did being a man, because it felt like they were being victimized by the same system. Being a monster seemed like the absolute best solution.”(9) Perhaps casting oneself in the role of the freak and going against the current involves regularly being the object of suspicion or living a life of self-destructive solitude—but never according to a formula.

Simultaneously one can discern in the works an open and at times hesitant relationship toward the very framework of the art concept. The choice of both medium and work process—which David Toop describes more closely in his text (pp. 155–161)—gives a certain freedom from being placed within an art-historical discourse, as would have been the case with painting. ”Untitled (Sunset)” (1999), painted in oil and filmed on Super 8, is one of Djurberg’s very first animations—expanding out from painting and into a time-based medium. The first stop-motion animations followed on from there, with female alter-egos such as exotic athletes, dancers, or gymnasts, sometimes interacting with animals. In due course these developed into increasingly surrealistic scenarios set to Berg’s music, populated by figures that are both captivating and monstrous.

The role of the Other, the divergent, however, brings with it a state of insecurity that stirs up fears in us and chafes against the expected order. The abject can be found in these cracks, gaps, and shadows where we don’t have the full picture laid out for us—an elusive phenomenon that cannot be expressed clearly in words or images, since it, in a psychoanalytic sense, arises before the subject or the object has been formed. It is similar to our experience of the sacral, which is found outside the actual reach of symbols and language. Writing about the body as code, Julia Kristeva holds that it becomes corrupted by dirt and ambiguity: “The body must bear no trace of its debt to nature: it must be clean and proper in order to be fully symbolic.”(10) With this dissolution—l’informe, the shapeless, as Georges Bataille termed it—an uneasiness arises in the viewer and an impulse to look for boundaries and clear identity.

Both Bataille and Hans Bellmer refused to submit to a conventional depiction of the naked body. Bellmer’s photographs of truncated dolls leave, as is often the case with Djurberg and Berg’s films, a creeping uncertainty regarding both identity and context.(11) Even his darkest, most nightmarish images have innocent, childish traits, which can partially be explained as a revolt against the restrictions of the adult world and a totalitarian state in the making. But, as a viewer, one occasionally gets caught up in a stifling feeling of simulated abuse, which one would rather push aside. Within our contemporary interest in the perverse image there is a fascination with its ambivalent charge—as an expression of both artistic freedom and compulsive vice. As Arrhenius and Sjöholm put it, perversion is both provocative and conservative— a double-sided figure that both mirrors a power structure and is the bearer of its countermovement.(12)

According to Arthur Danto, the use of “‘abject’ materials to produce experiences in viewers” was made legitimate by Marcel Duchamp’s ”Fountain” (1917), since in it ideas and meaning took precedence over assessments based on taste or style: “Duchamp, I think singlehandedly, demonstrated that it is entirely possible for something to be art without having anything to do with taste at all, good or bad.”(13) In works such as ”Étant donnés” (1948–49) he works with a form of parody reminiscent of Bataille’s, a game by and for the male gaze that may feel hopelessly outdated from a contemporary perspective. Surrealism’s exploration of irrational drives and compositions of different and absurd realities were based on a grotesque tradition that Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg are also related to. In their chaotic darkness with glimpses of light there is always a playful approach to both lust and repulsion: “Humour allows us to look at situations that are sensitive and hurtful in a simultaneously detached and close way.”(14)

It is here, in the rebelliously Dionysian, that the experience of l’informe in their work is primarily located. In disruptive and upsetting images that at times refuse to respect the limits of decency, but where the victim (when there is one) usually strikes back—an anti-authoritarian adult rebellion with decidedly more panache than Bellmer’s, as well as a carefree dismissal of the Enlightenment’s credo of an absolute truth outside ourselves. Speaking of modernism’s authoritarian ideas Slavoj Žižek holds that “there is no transcendent Truth from which we, as finite humans, remain forever cut off, either in the form of an Infinite Reality Divinity, which art cannot properly represent or in the form of a Divinity too sublime to be grasped by our finite mind.”(15) While power always wants to point toward a higher order and at the same time give a name to the ungraspable abject—in pointing out the other—Djurberg and Berg leave it open for everyone’s own interpretation, like in the anarchic father revolt in the finale of ”Florentin” (2004), or in the unbridled flow of vagaries arisen from primal lust in ”Delights of an Undirected Mind” (2016). The film ”Worship” (2016), with its related objects, mirrors the aesthetics of music videos in both expression and surface—the materials, the poses, the absurd scale. In its unreserved fetishism it brings to mind Kenneth Anger’s homage to hot rod culture in ”Kustom Kar Kommandos” (1965). This is a club and hip-hop aesthetic that is characterized by hedonism, materialism, and a sub-culture’s embracing community that includes a select few and that has its own, completely internal pecking order. For the artists, the core of the work is the depiction of a primal driving force in us that lies beyond a formulated sexuality—a drive to submit to and let oneself be drawn along, unhindered, by something greater than oneself: a feeling, a belief, material wellbeing, a lust for life, or a fear of death. Here the rapture and ecstasy of the moment negates the rational Apollonic order, like in ”Untitled (Acid)” (2010); or the spatial installation ”Black Pot” (2013), for which Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg for a time worked with a completely abstract aesthetic, formulated as a question regarding the essence of music. The wordless dialogue ended up in a spatial installation, where ethereally psychedelic forms arise out of the music around us.

Through the shadowy glades, closed chambers, and glaringly illuminated stages of the films and installations, a group of obsessed figures remain in perpetual motion as if condemned to devour one another. At the same time Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg now navigate within an entirely new topology—a new dimension of enveloping audiovisuality in the production of a virtual reality work, which in turn has strong links back to some of the very first black-and-white charcoal animations. The analogue, modelled figures or drawn images are, after all, sometimes still the basis of the digital. But the immaterially virtual should still not be considered to be the opposite of reality, as the postmodern philosopher Jean-François Lyotard posited. Such a completely sensory world can rather be compared to a daydream, that “opens up mines of meaning under the ‘platitude’ of the immediate physical presence.”(16)

At the end of a journey one may find that one has moved in circles—in an eternally repeated return, to come back to Nietzsche’s Zarathustra. The notion of the eternal return is based on the idea that all energy and everything living is predestined to repeat the same pattern over and over again: “Why do I have this urge to do these things over and over again?,” as the question goes in ”Tiger Licking Girl’s Butt” (2004). Among the completely new works for the exhibition there are those that capture that feeling—in ”One Need Not Be a House, The Brain has Corridors” (2018) we move in a loop to manically pulsating music through winding corridors where figures pass by, some of which seem familiar from previous films. Perhaps our memory creates a time-based model of the past and the future in order to be able to navigate in an eternal Now, as Jung imagined it? In the same way, memory builds the spatial perception of a room or a landscape. Our subconscious undeniably seems like a parallel universe at times—one that can only be glimpsed occasionally and that coincides with one’s “actual” life—a bit like something one could have seen in a film.

References

1 Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Intoxicated Song,” in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–85), translated by R. J. Hollingdale (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969), p. 328.

2 Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Les Hasards heureux de l’escarpolette (The Happy Accidents of the Swing), ca. 1767.

3 Eugene Thacker, “I. Three Quæstio on Demonology,” in In the Dust of This Planet (Hants: Zero Books/John Hunt Publishing). Thacker investigates how the supernatural horror genre can be used to reflect on an unthinkably dark future world and argues that the typical triumph of good over evil should be seen as “a certain moral economy of the unknown,” pp. 43–45.

4 Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Noontide Vision,” in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by R. J. Hollingdale (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969), p. 109.

5 Jonathan Meades, Magnetic North, episode 1, BBC 4, February 21, 2008.

6 The film Ewiger Wald was commissioned by the party ideologue Alfred Rosenberg and his Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (KfdK), under the working title Deutscher Wald – Deutsches Schicksal (German Forest – German Fate).

7 Paul Bishop, “Just a Moment? The Archaic as an Expression of the Eternal in Time,” in Time and the Psyche:Jungian Perspectives, ed. Angeliki Yiassemides (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), pp. 87–105.

8 Carolee Schneemann in the video Behind the Scenes: On Line, moma.org, 2010.

9 Sam Thielman about Emil Ferris in The Guardian, February 20, 2017. Ferris debuted in publishing with My Favourite Thing Is Monsters, a portrayal of a ten-year-old girl who lives a double life as a monster in 1960s Chicago.

10 Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982) (1980), p. 102.

11 Bellmer also worked with the notion of a “broken” language as a level of deconstruction. “The body is like a sentence that invites us to rearrange it, so that its real meaning becomes clear through a series of endless anagrams.”Jeremy Biles, Ecce Monstrum: Georges Bataille and the Sacrifice of Form (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007), p. 151.

12 Sara Arrhenius and Cecilia Sjöholm, Ensam och pervers (Stockholm: Bonnier Alba Essä, 1995).

13 Arthur C. Danto, Marcel Duchamp and the End of Taste: A Defense of Contemporary Art, 2000, http://toutfait.com/marcel-duchamp-and-theend-of-taste-a-defense-of contemporary-art/.

14 Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg in conversation with Charlotte Jansen, Elephant, February 14, 2018, https://elephant.art/5-questions-nathalie-djurberghans-berg/.

15 Slavoj Žižek, Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism (London: Verso, 2012), p. 254.

16 Jean-François Lyotard, Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime, translated by E. Rottenberg (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), p. 10.

Lena Essling

Lena Essling is a curator at Moderna Museet, where she has realized exhibitions like Marina Abramović: The Cleaner (2017), Adrián Villar Rojas: Fantasma (2015); Cindy Sherman: Untitled Horrors (2013); Eija-Liisa Ahtila: Parallel Worlds (2012), and Tabaimo (2009). She has produced commissions or screenings with artists including Harun Farocki, Natalia Almada, Yinka Shonibare, Omer Fast and Wael Shawky. At the 56th Venice Biennale 2015, she curated the Swedish participation of Lina Selander.

Catalogue ”Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg – A Journey Through Mud and Confusion with Small Glimpses of Air”

Authors: Lena Essling, curator at Moderna Museet and head of the film and video collection; Massilimiano Gioni, artistic director at the New Museum in New York; Patricia MacCormack is Professor of Continental Philosophy at Anglia Ruskin University, CambridgeDavid Toop; composer, musician, author and curator based in London.

Editor: Lena Essling

Softcover. English and Swedish editions.

Buy the catalogue: Moderna Museet Webshop