Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg, Dark Side of the Moon, 2017 © Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg / Bildupphovsrätt 2018

Introduction Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg

Pass through feverish daydreams about role play and desire, with comedy and darkness, set to hypnotic music. The films overturn any notions of normality and our understanding of memory, time and space.

Djurberg uses stop motion, a slow animation method where a series of stills give the illusion of movement. A process without a script in close dialogue with Berg, whose music adds layers of meaning. The presentation expands into the Museum’s collection of surrealist works.

The exhibition moves in archetypal landscapes – the dark forest, the illuminated stage, the closed chamber. Suggestive settings where dramas unfold between characters that are often closely related. Dark sagas merge with glossy club culture. But also social satire, in works that denude male power figures, social games and ideas about the supremity of mankind. A meandering voyage via labyrinthine underworlds, up into light and air, back down into the shadows – through wallpapered rooms and underbrush, coiling music loops and wormholes in time.

The Experiment

This installation takes the viewer to a prehistoric jungle, where the size of the vegetation makes humans insignificant in comparison. The plants and succulent flowers are both attractive and repulsive. When ”The Experiment” was shown for the first time, at the Venice Biennale in 2009, it was awarded the Silver Lion and represented a breakthrough for the artist duo.

The film ”Greed” reveals an interest in the Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini. Three men sporting insignia of the Catholic Church – the ring, the censer, and the purple cope – harass a few young, naked women who literally turn themselves inside out in order to please.

In ”The Forest” a couple are in a dark woods among toadstools and ominous birds.

In ”Cave” we witness a form of self-harming behaviour, when a woman’s body starts to take on a violent and conflicting life of its own. Victim and perpetrator are encapsulated in the same being. The scene is a cave with an interior that is eerily similar to a doll’s house.

The force and materiality that infuse human and non-human bodies alike seem to vibrate with life – and death.

These early works by Djurberg implied a shift from painting to the moving image. The first clay animations that followed were simple scenes with female protagonists. Gradually, these scenes grew more complex, peopled with captivating and monstrous figures, and accompanied by Berg’s music.

Early Animations

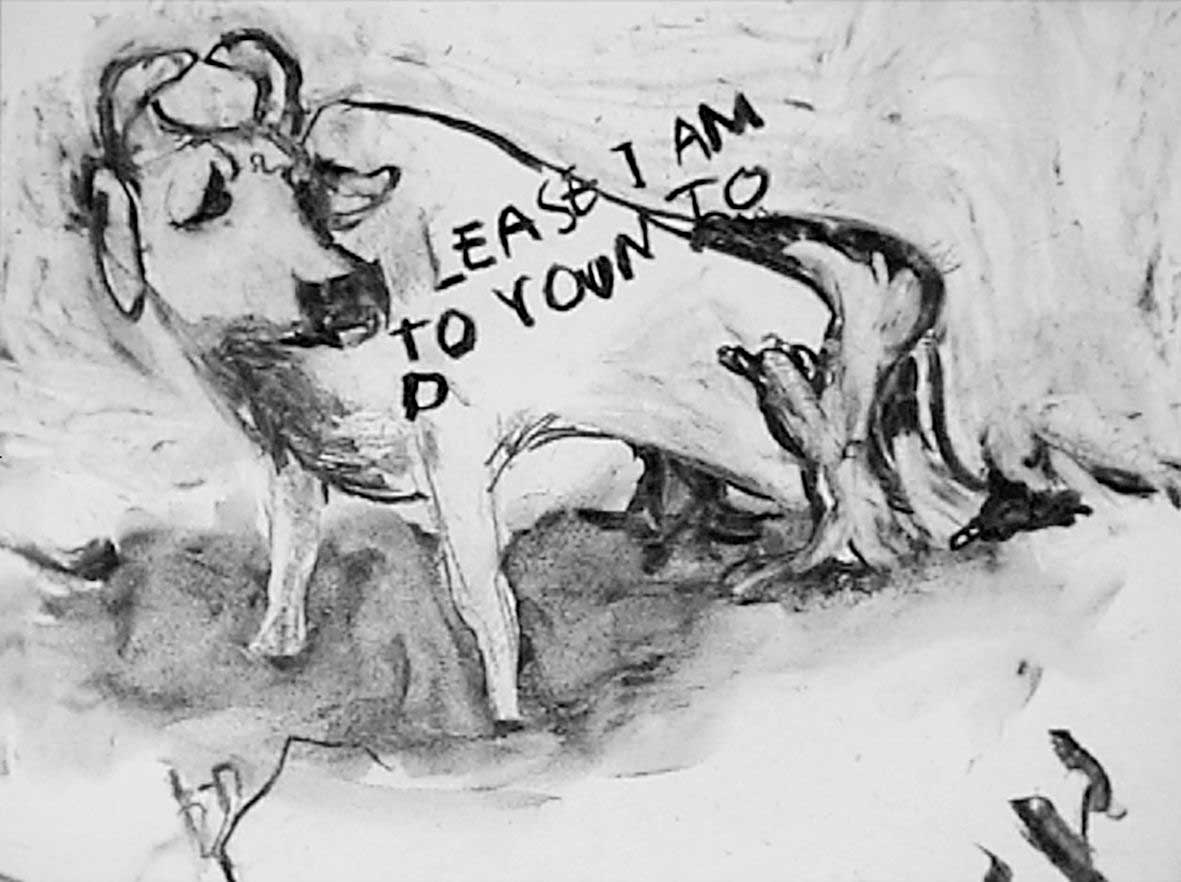

Two black-and-white charcoal animations form a passage between the sculptural worlds of ”The Experiment” and ”The Parade”.

In ”My Name is Mud”, the mud that bubbles up in a clearing grows into a mighty wave that sweeps across the landscape, engulfing everything. Returning to nature is a recurring theme – mankind is neither the centre of the film nor of creation here. In ”Untitled (The Wolf)”, we meet an obnoxious character that reappears in other works, perhaps the alter ego of the artist.

Nathalie Djurberg applies the written word in a way that allows image to overrule text. A “broken” language of unfiltered rejoinders appear and disappear, as fickle as everything else in the work.

These early works by Djurberg implied a shift from painting to the moving image. The first clay animations that followed were simple scenes with female protagonists. Gradually, these scenes grew more complex, peopled with captivating and monstrous figures, and accompanied by Berg’s music. These works convey an open, occasionally tentative approach to what art can be. The choice of style and method allows certain freedom from an art historic interpretation.

The Parade

A large flock of birds parades on what looks like an illuminated stage. Their body structures are varied. Feathered lumps totter on graceful legs, strut on short stumps, spread their wings, flap and squawk. These brightly-coloured sculptures consist of simple materials, such as painted canvas, wire and clay – with visible traces of how they were made.

We are said to resemble birds. Inversely, the birds in ”The Parade” seem human in their poses and gestures. But birds, which developed from dinosaurs, have existed long before humans, and connect us to something primordial and frightening. The two foppish men in bird masks tiptoeing around the woman’s body in ”I Wasn’t Made to Play the Son”, one of the five films that make up ”The Parade”, seem to be driven by primitive urges and sadistic desires, as they cut out parts of the woman’s body and yank out her teeth.

What takes place is clearly not “for real”. Yet the visualisation of repressed aggressions overwhelm the viewer. The violent scene reflects vulnerability and power struggles in the real world.

Underbrush

”The Potato” is shown in the middle of the exhibition, like a mythical beast at the centre of a labyrinth. Here, the cave reappears as the backdrop for a scenographic sculpture with cavities where three dark films are screened.

Traumas and assaults, deviations and compulsive behaviours recur in the works. Alienation is constantly just under the surface. As a whole, these works convey the impression of a tangled, impenetrable underbrush, a subconscious that we cannot always master.

In ”Once Removed on My Mother’s Side” the demented, hopelessly repulsive mother practically smothers her stunted daughter and carer. ”It’s the Mother” is a nightmarish scene where a mother is overpowered by her kids, who shove themselves back to an unborn state until their bodies merge. ”We are Not Two, We are One”, in which a boy tries to cope with life conjoined with a bushy wolf, also focuses on ambiguous identity.

Transformation and the relation to nature are central topics in the films shown next to ”The Potato”: the forest carelessly reclaims the dead body in ”Turn into Me”, the hunter dons the form of the killed walrus in ”Putting Down the Prey”.

Traumas and assaults, deviations and compulsive behaviours recur in the works. Alienation is constantly just under the surface. As a whole, these works convey the impression of a tangled, impenetrable underbrush, a subconscious that we cannot always master.

New Works I

In ”Snake With a Mouth Sewn Shut, or, This is a Celebration”, shown here for the first time, we see a small, abandoned child and a mother dragon’s mental breakdown in a claustrophobic room. The text fragments in the film show their desperate outcries. Mothers are a stock character in stories and myths – chastising and tender, caring and deadly. The mother figure in this work is unreachable, drawn into a painful struggle.

The latest works include ”Cheer Up – Yes You Are Weak and Yes, Life is Hard”, portraying a group of party animals at a table laden with greasy food with cigarette butts and beverages spilling out of tipped plastic cups. The festivities should be over, but perhaps they just began.

In ”Delights of an Undirected Mind” the nursery is filled with creatures resembling cuddly toys that behave like an erotically uninhibited menagerie; a tiger, an octopus, a crocodile, a girl wearing lipstick and pajamas, a hare, two cucumbers, and a plethora of other creatures, playing violent games interspersed with bottle feeding and tea parties. A virile matador makes precise incisions in a soft cake.

The Black Pot

Originally, their collaboration started with Nathalie Djurberg’s films, for which Hans Berg composed a soundtrack. For ”The Black Pot”, however, Berg composed the music first, and then Djurberg created the visual representation. The installation was made during a break from city life, when they were living in an isolated area and exploring the essence of music.

Unlike previous pieces, this work is entirely abstract. Figures and scenes have given way to pulsating and morphing shapes and colours in a cyclical course where things arise and disappear, only to reappear in a new guise. The forms migrate from one screen to another. It resembles how Djurberg and Berg describe their method: they work not to find an ending – the process itself is what matters.

The animation in ”The Black Pot” is based on drawings made with oil crayons. This is a painstaking and slow technique: Djurberg draws on a latex-coated surface, then partially scrapes and wipes off the colour with a spatula and a rag before drawing the next sequence.

New Works II

Three films where the soundtrack is an essential element are shown on large screens:

”Worship”, with its accompanying sausages and diamond-encrusted bananas, reflects music video aesthetics – its poses, fetishism, and absurd scale. The embracing community and harsh pecking order of club culture. What it is really about, beyond the bling, is perhaps a primal urge to devote oneself to something greater: a feeling, faith or pure lust for life.

”Dark Side of the Moon” is set in a forest clearing, where the desires of the characters revolve around a mysterious cabin where only the chosen few are allowed inside.

In ”One Need Not Be a House, the Brain Has Corridors”, pulsating music accompanies our journey through winding passages where characters appear, some of which are familiar from previous films. A portrayal of dissolving memory, space and time.

In an adjoining room ”My Fixation With Making You Happy and Content” is shown, a group of birds having a meal together. The scene is strained in a way that may seem familiar – tensions caused by etiquette, competition or stale relations.

It Will End in Stars

Several paths intersect in the completely new work ”It Will End in Stars”, an immersive audiovisual experience created in virtual reality (VR). Here, again, is the deep forest, associated with collective primordial memories that resurface in folk tales and horror movies. The black-and-white charcoal drawing that sets the mood in this work is familiar from early films. The wolf recurs as our quaint guide through a shadow world with portals to other, entirely different dimensions.

Through VR, the artists try a new narrative method, but in their own way, based on traditional analogue techniques – hand drawings and sculpted figures that have been painstakingly scanned and animated. The work is experienced in a setting that combines the hand-crafted style with digital technology. It reminds us that the immaterial and the virtual should not be seen as the opposite to the real. Instead, the experience might resemble daydreaming, where we are sometimes closer to our feelings and impulses than in our physical “reality”.

The work is active at 13.00–17.00 during the exhibition’s opening hours.

Surrealisms

Surrealistic tendencies can be detected in Djurberg and Berg, even if they take a different form today. Ideas about the boundaries and transgressions of the body and identity have metamorphosed through decades of popular culture and gender politics.

The part of the exhibition that spills over into the Museum’s collection galleries features Hans Bellmer, Max Ernst, Meret Oppenheim and other surrealists and dadaists who can be related to the artistic practices of Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg. Bellmer’s mutilated dolls, Oppenheim’s white shoes trussed like a chicken on a serving plate, and the bird-insect-planthuman hybrid that Max Ernst painted in 1931 – bizarre expressions that are sometimes close to the themes in Djurberg’s and Berg’s twisted animations and objects. The Surrealist collection is reinstalled by curator Jo Widoff.

From the 1900s and onward, surrealism has explored man’s irrational sides. This approach sprang from the rebellious dada movement, which deplored war, despised the bourgeoisie, and rejected “tastefulness”. Their objects were invested with erotic undertones and often lean towards the sadistic, compulsive and fetishist – addressing the dark territory of the psyche, untamed nature and the desires of the flesh.

Guidade tours Surrealisms

In Swedish

Tuesdays at 13.00

Thursdays at 15.00

Sundays at 15.00

In English

Saturdays at 14.00

Read more: Surreal summer