Håkan Rehnberg, Untitled, 2014 © Håkan Rehnberg / Bildupphovsrätt 2016

Håkan Rehnberg & Daniel Birnbaum

Daniel Birnbaum: Starting with the paintings: what are these pictures?

Håkan Rehnberg: As always, they are paintings made in one session, the paint is applied wet on wet. I work on sandblasted acrylic glass sheets, with oil paint and painting knives. First, I apply the paint in dabs and fragments, covering the surface with several layers. Then I use a small painting knife to reveal parts of the paint all the way down to the support.

DB: You paint by removing paint?

HR: I move the paint around, as if ploughing a half-unknown terrain, with erratic and unpredictable gestures. The basic idea is that layers visually and physically change places. I end the moment the painting has attained an ultimate expression of exactness, often in an ambivalent state of euphoria and despondence.

In some paintings I try my work against Carl Fredrik Hill and his late paintings of beaches, with seaweed and sludge glimmering in the shallow tide. It’s like a surface that appears and then withdraws; everything ends up either under or over a lustrous surface of water, writhing in the tide, at once both exquisite and repulsive. It’s not the visual connection I’m after but more the idea of a base and a boundary that are dissolving.

DB: The terseness and the indefatigable quest for some kind of origin appear to have evolved over the years into more eventful painting. Have you grown more frivolous?

HR: My basic attitude is absolutely the same. It’s not really a quest for origins, but more that the “situation” has to be continuously re-established. But it’s as though I spend more time on painting now, I don’t just establish it, I actually practise it. That might be frivolous – or at least more sensual.

DB: Your orientation is contrary to the Swedish art scene’s emphasis on the USA. This applies to your interest in philosophy, which primarily focuses on German and French ideas. But perhaps also to art?

HR: I saw the Joseph Beuys exhibition at Moderna Museet in 1971. It made a deep impression on me, especially since I was totally unprepared and very young. His works impacted on what I did in my first years at the Royal Institute of Art in the mid-1970s. Fairly soon, I moved on in a much more abstract direction.

In New York I came in contact with the painting of Brice Marden and Robert Ryman. I saw a couple of wooden boxes by Donald Judd that were installed with such wonderful precision. Blinky Palermo was another early discovery. What I was working on myself was a hybrid form of object and painting. Despite these pivotal American impulses, my eye was entirely Central European.

DB: Some of the sculptures remind me of rudimentary buildings, and perhaps even to some kind of puzzling furniture.

HR: Minimalism has always been essential. It was decisive to me as a budding artist in the early 1970s. Something radically repellent yet physically present. What used to appeal to me was the sight of how the object related to the place. But also the use of prefabricated materials and the reduced processing. I was looking for something that was neither representation nor construction, but more of an elementary action that would transform an item or a material into an art object.

DB: How do you envision this exhibition?

HR: It’s not a narrative or a presentation, but rather a precarious situation. To me, the work of art stands for an action of resistance, no understanding, no usefulness, but sense of wonder and a vertiginous questioning. Something historically decisive took place when the painting was removed from its frame and the sculpture lifted from its pedestal. This was a process that went on in Mondrian, a care for the painting and paint as an object, how the work was finished along the edges, how the paint was interwoven in layers. We can also see this in Barnett Newman. How his early paintings were a battlefield for metaphors, before transforming at a crucial moment into material events of paint. To me, this is the transition from the arcane to the inscrutable.

DB: The inscrutable – is that what keeps you moving on?

HR: Yes, art is not something you learn, own, or even practise, but the compulsion in every situation to seek the point where you fall off the stage.

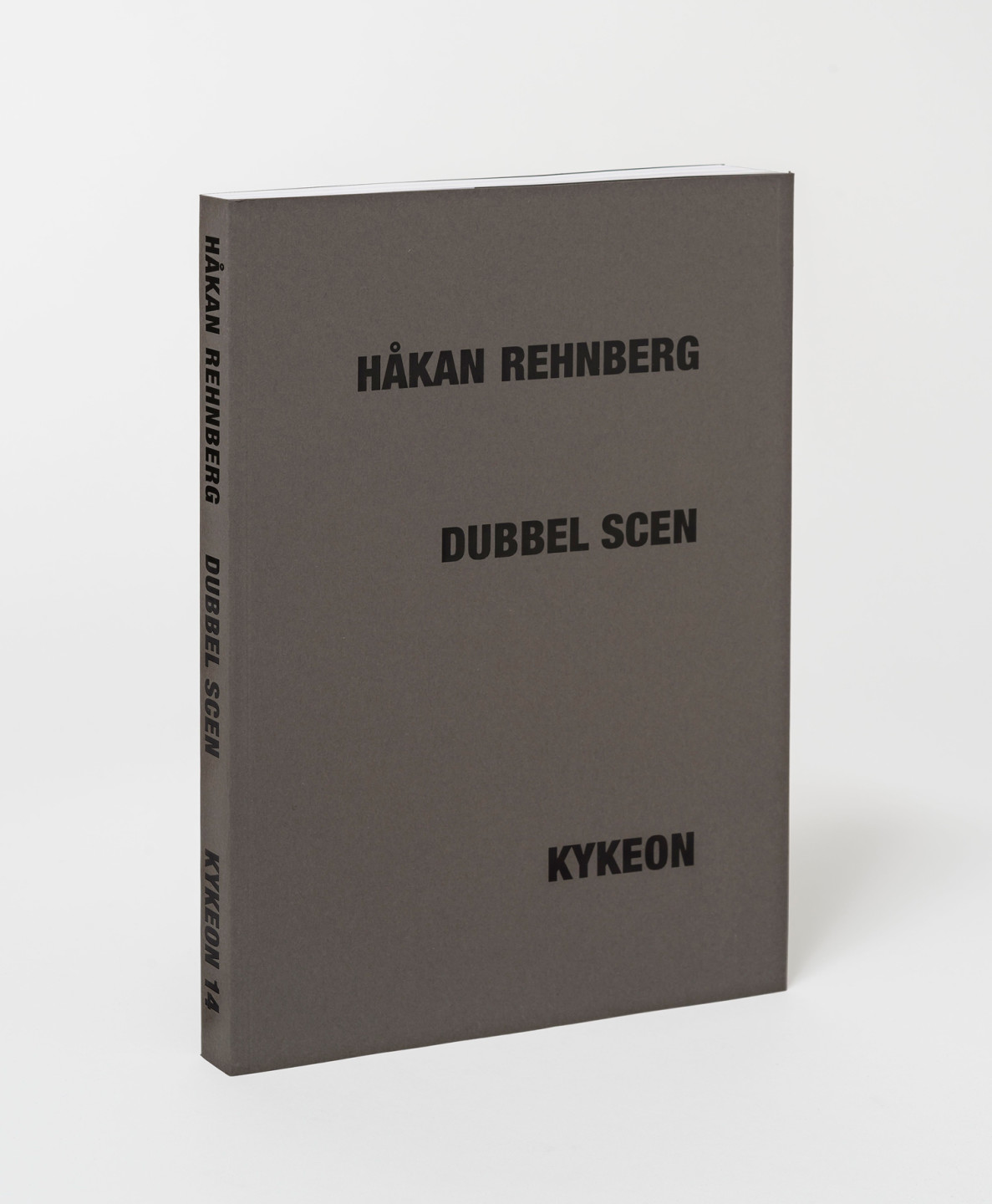

The conversation is published in the catalog produced for the exhibition. The book is part of the Kykeon series (Propexus) and also features texts by the artist himself and a series of newly written essays. The catalgoue is in Swedish only.