Hilma af Klint, The Swan, No. 1, Group IX/SUW, 1915 Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

Topics and central works

Paintings for the Temple

Between 1906 and 1915, Hilma af Klint created her central oeuvre, her Paintings for the Temple. It comprises of 193 paintings in various series and groups. The overall idea is to convey the knowledge of how all is one, beyond the visible dualistic world. The temple to which the title refers does not necessarily relate to an actual building but can rather be seen as a metaphor for spiritual evolution.

Hilma af Klint described her process: “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

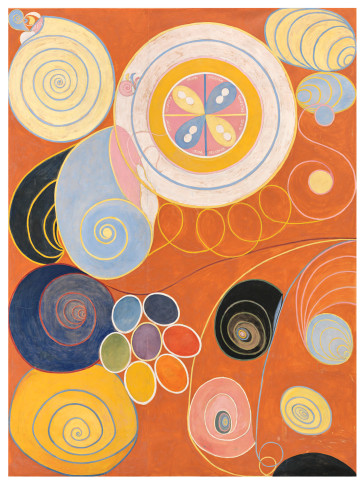

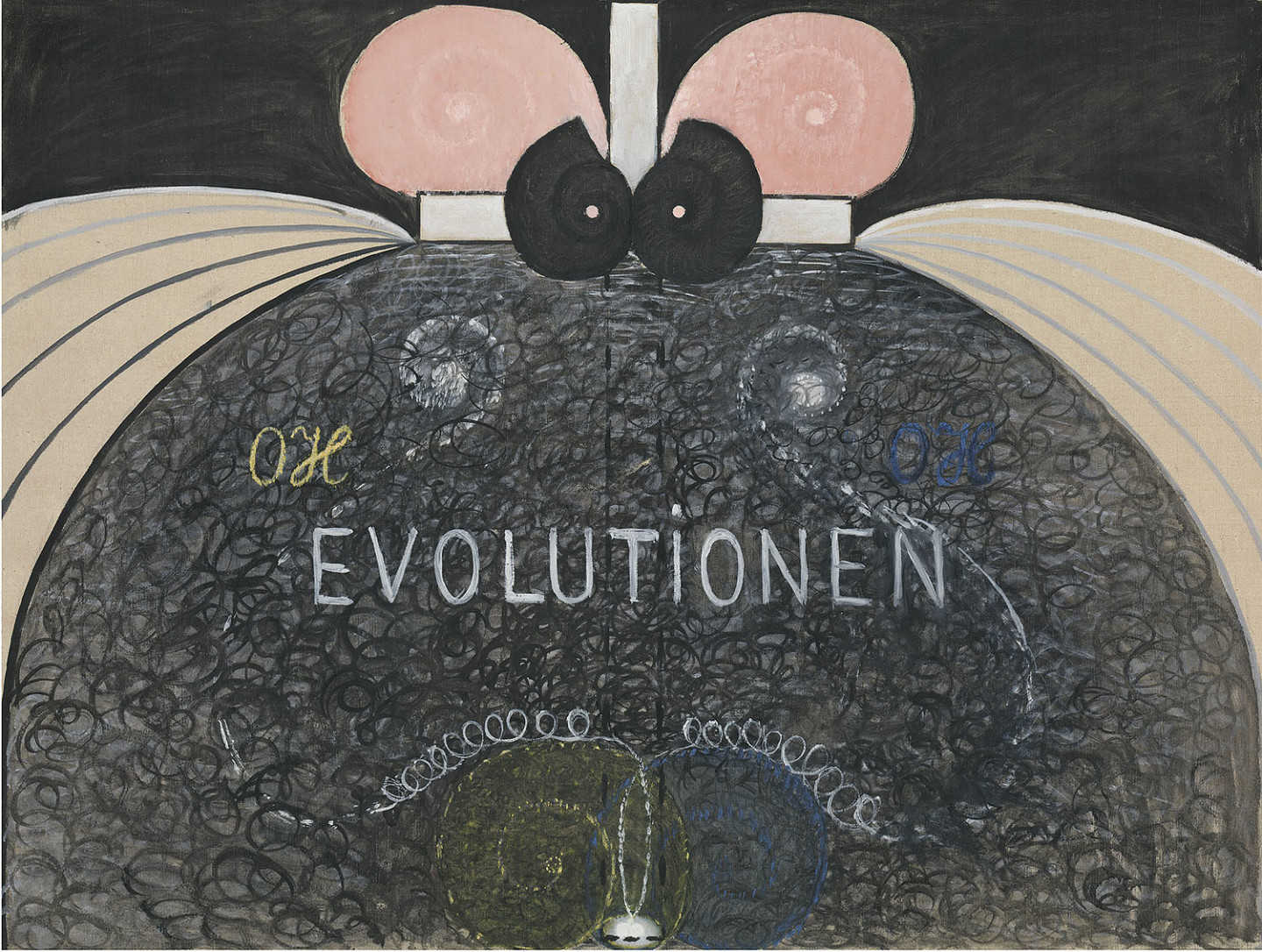

Between November 1906 and April 1908, she created the first part of Paintings for the Temple, which consists of 111 images in varying formats. The abstraction of this first part of the project is often based on forms taken from nature. The Ten Largest from 1907 illustrates the four ages of mankind: childhood, youth, maturity and old age. Some words and plant forms are discernible in these otherwise abstract compositions. Evolution from 1908 relates to development and processes, to how the world and matter have arisen from the spirit.

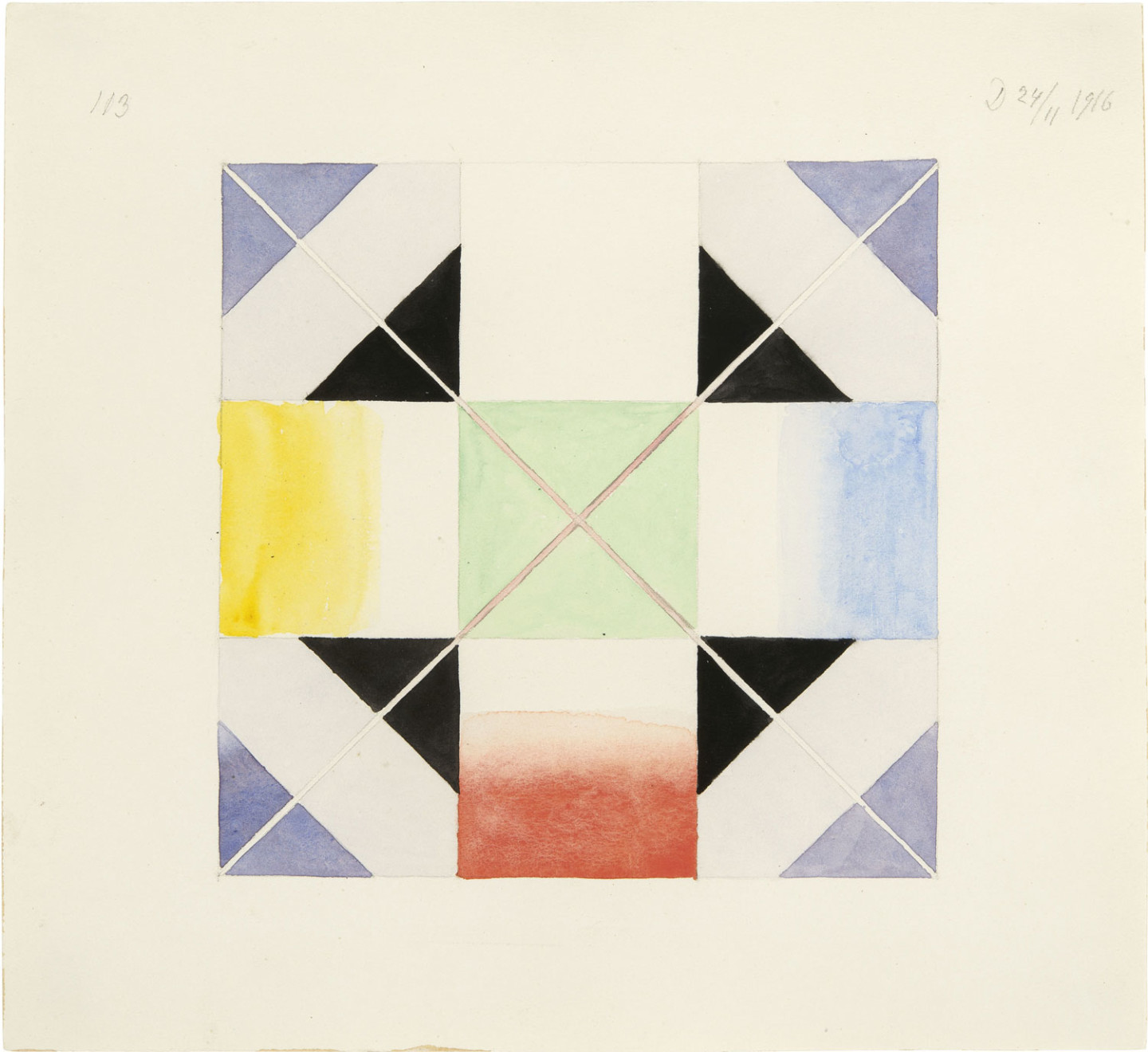

From 1908 until 1912, she ceased working temporarily and studied esoteric Christianity and Steiner’s literature on Rosicrucianism. Prior to 1908, Paintings for the Temple were partially influenced by a theosophical content, but when she resumed her work on the series in 1912, the Christian symbols had become more pronounced. Her abstractions were now of a more geometric nature. Hilma af Klint no longer experienced that her hand was being guided. Her own interpretations increasingly found their way into her paintings, even if she continued to be in contact with the high masters. The suite called The Swan was painted in 1914–15. The swan symbolises the ethereal in many mythologies and religions. With varying degrees of abstraction, Hilma af Klint explored polarities in these paintings, through a black and a white swan striving for unity.

Altarpieces sum up all the previous series where the spirit migrates downwards through the material world, before turning upwards again. The equilateral triangle is a central symbol in many cultures and religions. The triangle, which reaches towards the sun, can be seen as an upward development through the spheres, while the inverted triangle describes the opposite process. In the middle of the circle in the third and final painting, two triangles are combined into a six-armed star. This star is an esoteric symbol for the universe.

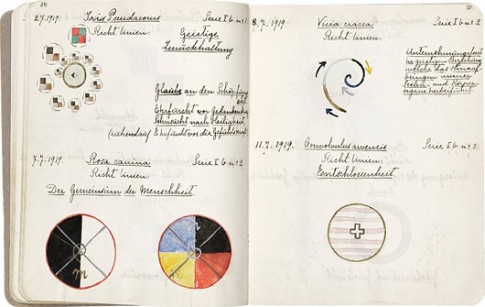

Parsifal

As a medium, Hilma af Klint was both open and sensitive, but she devoted a great deal of thought to the possible interpretations of the messages from the spiritual world and the meaning of the images she painted. After completing the series of Paintings for the Temple, she devoted herself to trying to comprehend the messages she had conveyed, for instance by writing about the spiritual context of the world, as she understood it. This resulted in the more than 1,200-page text Studier over Själslivet [Studies on Spiritual Life] from 1917/18.

In her artistic practice she also continued exploring and trying to understand her earlier work and the greater context of life in general. The Parsifal series from 1916 deals with this quest for knowledge. In the first image, a voyage through darkness towards the white light at the centre of the spiral is depicted. This journey could be said to correspond to the inner voyage that Hilma af Klint had undertaken when she had finished Paintings for the Temple.

According to the medieval legend, Parsifal was one of the Knights of the Round Table. Together with King Arthur, he searched for the Holy Grail. The grail legend can also be interpreted as a story about the search for spiritual knowledge. It has a central position in the esoteric tradition and also inspired Richard Wagner (1813–1883) to write his famous opera Parsifal in 1882, which was performed at the Royal Opera in Stockholm in spring 1917.

Religions, Flowers and Trees

1920 was an intensely creative year for Hilma af Klint. In several series of small oil paintings, she for instance explored the great world religions. The religions are based on duality, that is, a division into opposites, such as good and evil, order and chaos. None of them appeared to Hilma af Klint to attain unity.

During her study tours to Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland, she encountered the anthroposophical approach to art. According to Rudolf Steiner, anthroposophy strives to see mankind in relation to the spiritual dimensions. It was not just a doctrine to him, but a method for conducting independent research into these spiritual realms. Influenced by his views, Hilma af Klint gave up painting geometric compositions. After a two-year hiatus, she instead began portraying the spiritual dimension in watercolours relating to nature, as in the series On the Viewing of Flowers and Trees. Thus, when she was more than 60 years old, she was ready to change her entire approach once more. In earlier images, she had contrasted the outer appearance of plants with their essence in geometric form. She analysed both the microcosm and macrocosm and portrayed them as mirror images of one another. The relationship between them can be summarised with the esoteric motto “as above, so below”.

Read more: Symbols in Hilma af Klint’s imagery