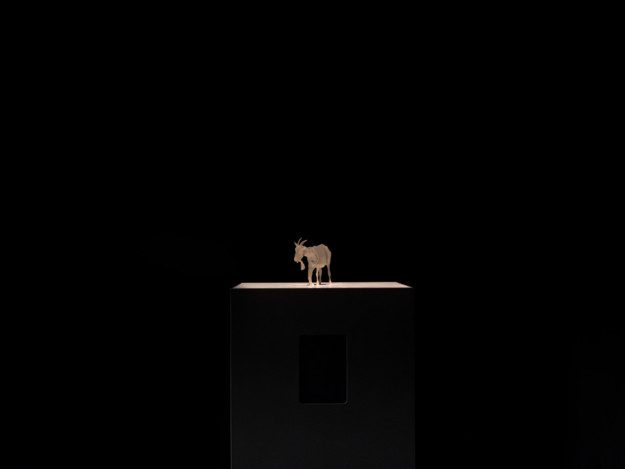

Laurie Anderson, Absent in the Present: Looking into a Mirror Sideways, 1975 © Laurie Anderson

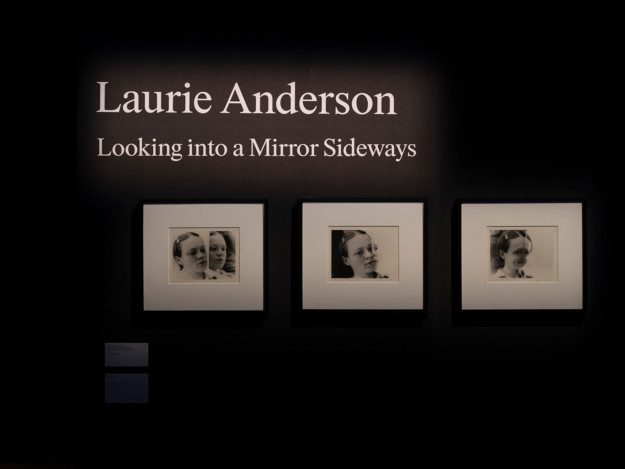

Laurie Anderson

Looking into a Mirror Sideways

1.4 2023 – 3.9 2023

Stockholm

Since her breakthrough in the mid-1970s, with performance and video works, Laurie Anderson (b. 1947) has risen to prominence also as a writer, composer, and filmmaker. Listening, language and storytelling are essential elements in her interdisciplinary practice, which spans from philosophical and personal contemplations to activist interventions on burning political issues.

Anderson achieved her international breakthrough as a pioneer of electronic music, and today she works at the cutting edge of new arts technologies, like virtual reality (VR) and artificial intelligence (AI) – but is just as likely to employ timeless expressions like voice, painting, or charcoal drawings.

The different parts of Laurie Anderson’s multifaceted production form a tapestry of storytelling that weaves together observations around the human condition, the dreams of nations, the transient now, as well as dystopian visions of the future. – Lena Essling, curator

Laurie Anderson, Drum Dance, from Home of the Brave, 1986 © Laurie Anderson

Laurie Anderson, Drum Dance, from Home of the Brave, 1986 © Laurie Anderson

Looking into a Mirror Sideways

“Looking into a Mirror Sideways” is Laurie Anderson’s largest solo show to date in Europe. It presents a narrative of time, place and existence.

Here, a representative selection of the artist’s works from the 1970s up to the present day is complemented with brand new, site-specific productions: conceptual art, performance, innovative musical instruments, compositions, stage shows, as well as activist art and political art. The exhibition serves as a forum for both physical materials and techniques – painting, sculpture, analogue photography, sound tapes and film strips – and new digital worlds.

In several works Anderson explores issues of subject and of identity, the roles we take and are given, for example, via the artist’s Swedish-born paternal grandfather, Axel Efraim Anderson (1881–1963).

Exhibition Guide

Hear Laurie Anderson’s and curator Lena Essling’s thoughts and ideas on the artworks in the exhibition on our Exhibition Guide.

– I’m trying to look into the mirror sideways because you know, if you look straight in you’re not going to necessarily see the whole thing, she says in the film.

Visit the Exhibition Guide: Laurie Anderson – Looking into a Mirror Sideways

Instruments and performance

Music and voice are the foundation of Laurie Anderson’s work. Speech, pauses, and even the act of listening, are all central to her compositions and performances. Anderson has experimented with site-specific sound works since the 1970s. Her compositions are influenced by geometry and language, as well as everyday sounds. Over time she has been combining music with performance, film, and technical innovation, culminating in multimedia stage productions like “United States I–IV” (1983) or the opera “Moby Dick” (1999).

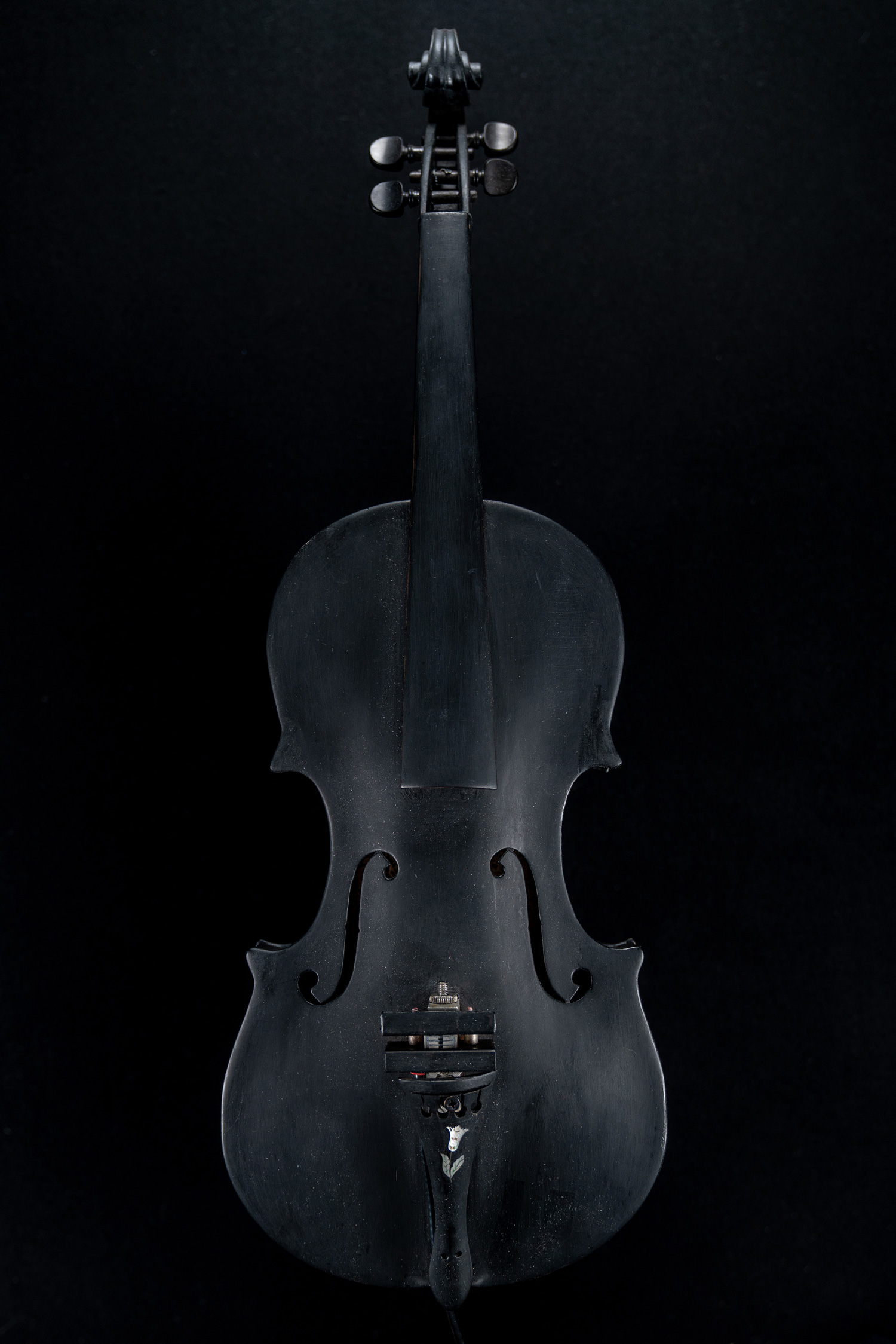

She has also developed new instruments. In “Tape Bow Violin”, the horsehair in the bow is replaced by audio tape. The voice on the recording is transformed into repetitive sounds, words void of meaning even as they carry the soundscape. In “Drum Suit” the body becomes an instrument, with parts of a drum machine sewn into overalls, in “Drum Glasses” the cranium becomes a sound box. The 1990s high-tech work “Talking Stick” samples sounds from the stage that are replayed in a new form.

In “Citizens”, the room is filled with the metallic sound of figures sharpening knives, each to their own rhythm. An abstract sound piece that doubles as a portrait of friends, and a snapshot of the charged atmosphere around the US election year of 2020.

Language and memory

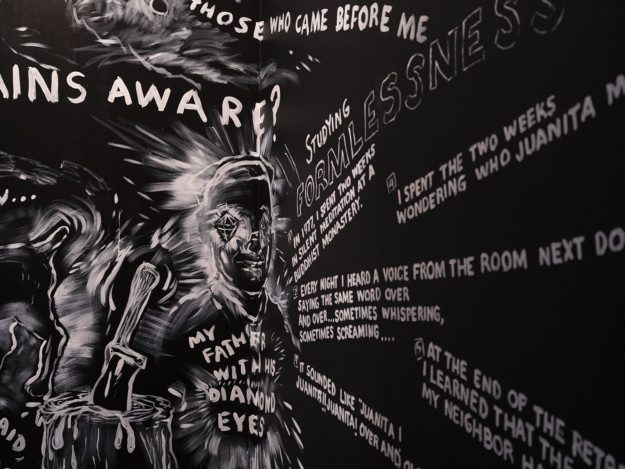

An interest in language and media runs through Laurie Anderson’s practice – as a theme in her written and narrative work, but also as raw material and phenomenon.

In the 1970s, Anderson’s close friend and collaborator, the American author William S. Burroughs (1914–1997) compared language to a virus from outer space. Language, Anderson claims, is a self-generating system that we never fully control – the relation is rather that it plays us like an instrument. Today’s AI technology can auto-generate entirely new texts from a wide range of sources, deftly imitating individual tone and style.

How we choose our words in any given moment, or how we narrate an experience, shapes our memory and identity. Some works in this room represent early experiences that came to determine Anderson’s sense of the power of words. Such moments, which come to shape the rest of our lives, are sometimes described as vertical time – a flash that seems to cut through all other experiences like shafts through the linear experience of the passing of time.

Persona

New York in the 1960s and 1970s was a turbulent, creative environment, which Laurie Anderson later compared to the vibrancy of 1920s Paris. Her circles were inspired by the international Fluxus movement, prizing ideas above traditional art objects. In accordance with the Zeitgeist, the street became their studio and collaborations thrived. An artwork could take the shape of a reading, a dance across city rooftops, or an artist-run restaurant.

Among Andersons’s earliest works are sculptures in simple materials linked to the body. Mudras uses Buddhist hand gestures to cast language as image, and “When You We’re Hear” is a sound sculpture that can only be experienced by the person touching it.

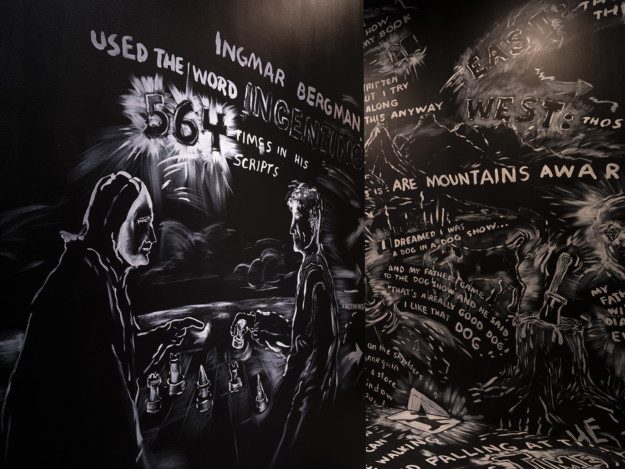

Photography and writing are tools for exploring subject and object, dream and reality. The camera lens becomes a mirror when Anderson explores her Swedish roots – by repeating learned phrases or imitating camera angles and gestures from Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona” (1966). On stage Anderson assumes a variety of alter egos, at times by altering her voice with the help of technology, such as the masculine voice of authority.

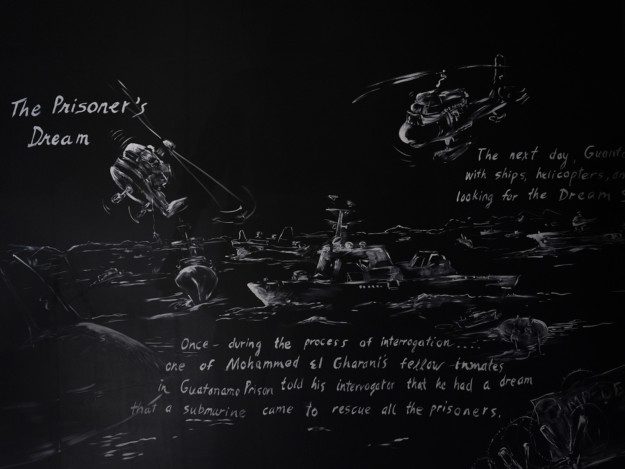

Time and body

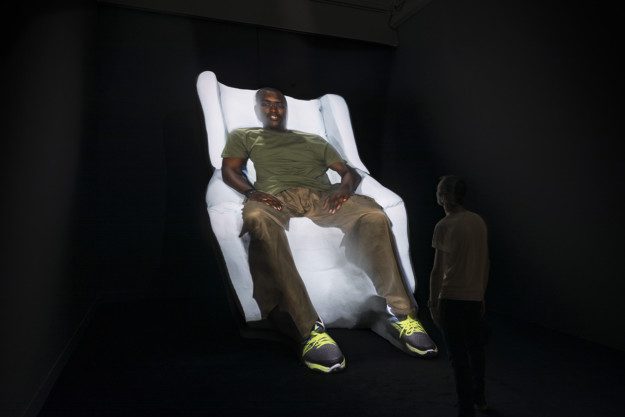

In the aftermath of 9/11 Anderson staged a manifestation in collaboration with Mohammed el Gharani (b. 1986). As the youngest prisoner at the Guantánamo Prison – accused of plotting a terrorist attack at the age of 12 – he was released and deported from the US in 2009, without any valid citizenship. The work’s title, “Habeas Corpus”, is the legal principle meant to protect against arbitrary imprisonment. During a New York City concert with Anderson in 2015, the stateless refugee met the public in a monumental livestream to tell his story from a studio in Ghana. The work highlights a political situation that turns individuals into pawns in a game, but also the nightmare of being robbed of one’s identity, time, and memories.

Laurie Anderson has worked recurrently with speaking sculptures, analogue holograms of sorts. Distance in time and space is suspended when someone materializes in a room, even as the multiple layers of the work – sculpture, sound, projected images – marks the actual distance to the viewer. “Presence that refers to absence,” as French cultural theorist Roland Barthes described the art of photography. Is direct, unfiltered communication between people an illusion?

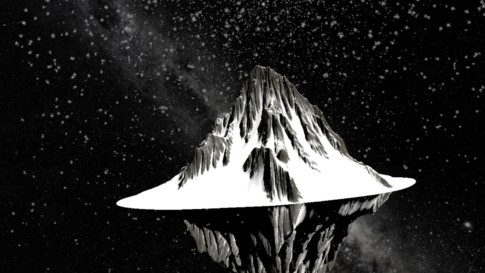

To the Moon

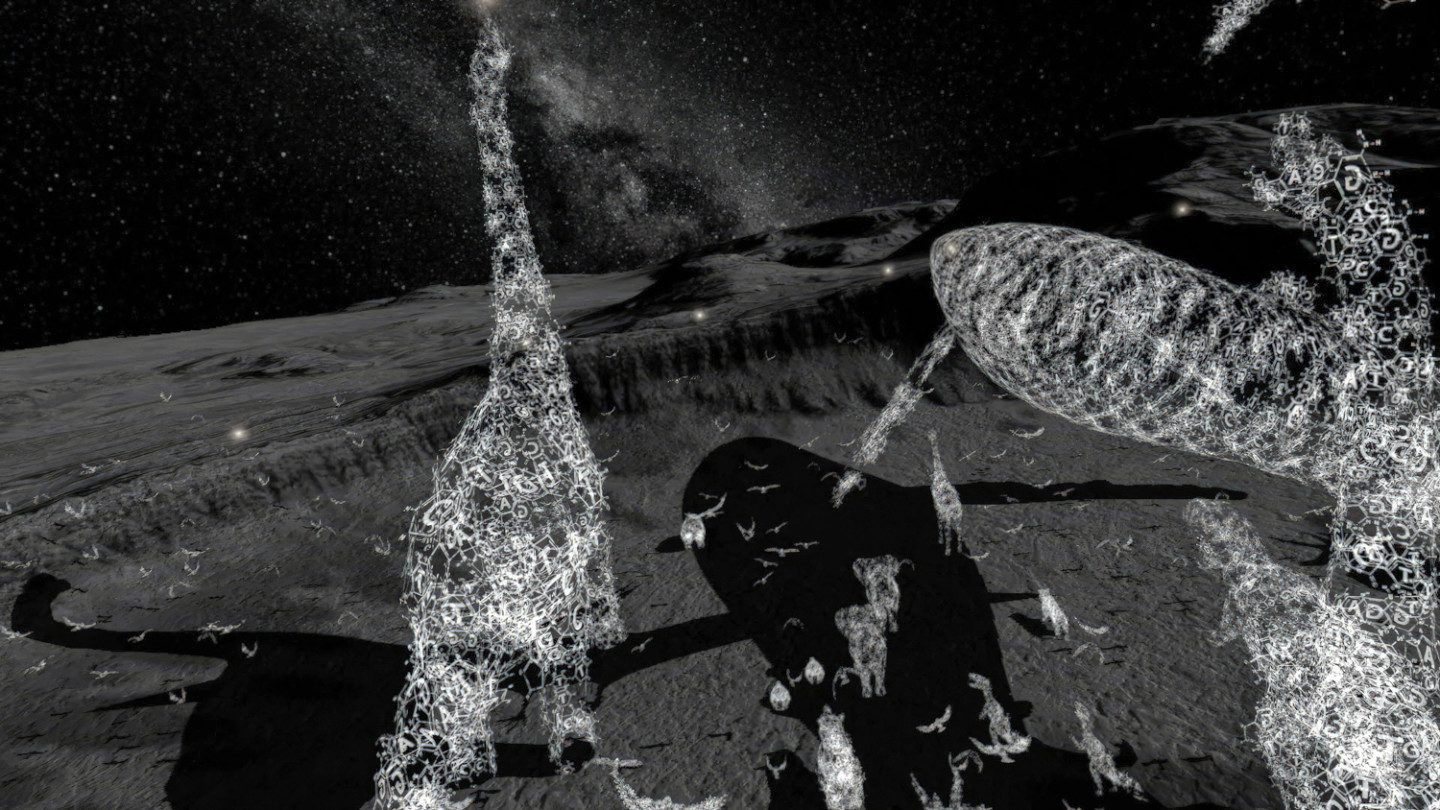

In “To the Moon”, Laurie Anderson and Hsin-Chien Huang employs virtual reality technology to transport us to a place beyond the physical world. …

To the Moon

ARK

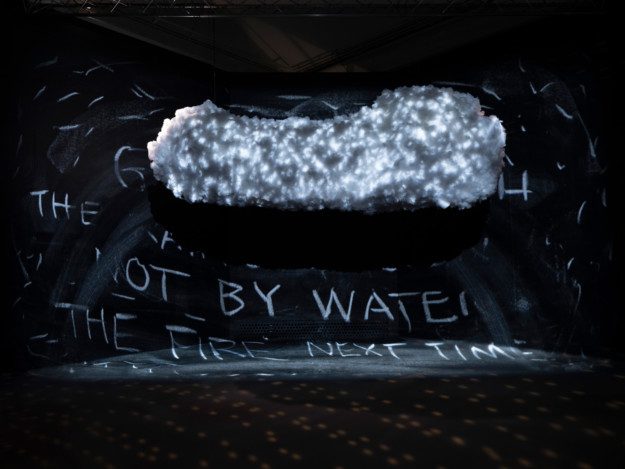

The flood in Laure Anderson’s “ARK” is not a punishment for man’s sins like in the Bible story, but rather the result of iCloud bursting, …

ARK

Soffvisning