Soda_Jerk, Undaddy Mainframe, 2014 © Soda_Jerk

A Map of the Show: Coordinates in Time, Space, and Ideas

Text: Lars Bang Larsen

The more you think about art and technology, the more history opens up, origins multiply, and the present begins to fray. One of the histories of this relationship can be traced back to the late 1960s, a point in modernity when new media – film, computing, telecommunication, and so on – began to make their mark on art making, just as they did on everyday life, with means and approaches that irritated humanist worldviews and often were accompanied by controversy, sometimes to the point of being excluded from the category of art.[1]

Two decades into the twenty-first century, the art-technology relation has transmuted from what it once was, not least because of its integration into a contemporary technosphere. This is where “networked digital information technology has become the dominant mode through which we experience the everyday.”[2] Overwhelmingly present, technology now appears to be a realized condition, a form of being. Against this background, it might seem counterintuitive or even anachronistic to single it out as if it were separate from anything else. I want to argue, though, that the art-technology juxtaposition remains relevant. As a theme handed down from the ’60s, its mutability encompasses a longer timespan than that defined by the rise of the Internet and the present hegemony of digital mediation, and thus other trajectories can be traced over and beyond our present livingwith and being-in digitality, providing the opportunity to assess historical change and to consider directions that will shape our future.[3] What is more, the proposed difference between technology and art can be set to work as a differentiated or even dialectical view of technological reason that is necessary for our – critical, interpretive, playful, embodied – interaction with it.

”Mud Muses – A Rant About Technology” doesn’t try to capture technology’s thing in itself; that is, its perceived contextlessness and the newness courted by an evangelical faith in technofixes and change for its own sake. Instead, the exhibition takes the art-technology link as a form of collective time travel, both situated and imagined, that departs from the Western techno-patriarchy and sets out toward other conceptual and material tangles, and new geopolitics. Seen from here, perhaps the only thing that will become clear is that our moment’s actual encounter with technology does not imply that there is resolution. Instead, there is energy and insight to be found in schisms and struggles and places where things don’t add up: How we embody technology through behaviours that it massages into us; what it promises us, or what we want it to promise us; and the real and virtual worlds it creates for us, and we for it.

Mud Muse and the Active Human Interface with the Material World

”Mud Muses – A Rant About Technology” owes its title to Robert Rauschenberg’s installation ”Mud Muse” (1968–71) and science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin’s 2004 essay “A Rant About ‘Technology,’” respectively. The exhibition uses, but also reads against, these sources in order to cut across a vast thematic terrain and attempt to identify some first encounters between art and technology since the late ’60s, paying particular attention to junctures where this relation heads in a new direction.

Performing a random, boiling encounter between sound and artificial goo, Rauschenberg’s ”Mud Muse” utters its opaque message from a dirty and flatulent minimalist framework. In a large vat, sounds, in the form of compressed air, pass through valves at its bottom to make little ploppy geysers erupt in thousands of pounds of synthetic mud made from a recipe of glycerine and finely ground volcanic ash. A hi-fi system, which is a visible part of the installation, plays recordings of various high-frequency sounds through the mud, setting off new unsounds that become part of the work’s recursive, mud-kicking action.[4]

Deflating expectations of push-button abstraction and numerical efficiency, and instead turning data into so many stains on the real, ”Mud Muse” throws up a lot of issues. By titling the show ”Mud Muses”, plural, the ludic attitude of Rauschenberg’s artwork is extended and multiplied, allowing for the question of technology to be continuously reopened. ”Mud Muse” is hereby turned into MUD, a Multiple User Domain, to repurpose the acronym for the virtual worlds of the first online role-playing games. After all, who will ever know what is the mud muse that turns our meeting with technology into a queer mess? Rauschenberg’s strange installation refuses to sell you an agenda or detail its bottom line, let alone allow any harmonization of the art-technology relation. That it is an artwork for the twentyfirst century lies in its acceptance of the apocalypse with a shrug and a burp. At a time when society’s interest and investment in technology is colossal, ”Mud Muse” remains an example of technology on art’s premises. It is in this sense that Rauschenberg’s work will come and go throughout this essay.[5]

In “A Rant About ‘Technology,’” reprinted in this catalogue, Ursula K. Le Guin responds to a critic who accuses her of not writing “hard sci-fi” because of the absence of advanced technology in her novels. Le Guin concurs that she might be a writer of “soft sci-fi” and counters with this striking definition: “Technology is the active human interface with the material world.” This definition of technology, more value-neutral and non-deterministic than many, takes the concept beyond objects of substance such as “a computer or a jet bomber” and undoes its providential essence of being always and only modern. Instead, as an object for sci-fi thinking, technology is uprooted from the rationality of the present and rendered movable in time and space. In fact, Le Guin’s brief text is not really a rant, but more like a problem-oriented meditation that steers away from both Luddism and rationalism, conveying instead a different sort of wonder.

Collective Brains of Artistic Intelligence

Rauschenberg’s work is also an archival fact that stands in for a certain history of art and technology as it has played out at the Moderna Museet, where the work entered the collection in the early ‘70s.

Between 1967 and 1971, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Art and Technology Program (known as A&T) paired artists with private corporations to produce new art works. For the production of ”Mud Muse”, Rauschenberg wished to collaborate with personnel of the aerospace-oriented industrial conglomerate Teledyne Inc. Curator Maurice Tuchman cited a “gathering aesthetic urge” among artists “to gain access A Map of the Show: Coordinates in Time, Space, and Ideas to modern industry” for the program’s art and business collaborations: He compared this urge with “the programs of the Italian Futurists, Russian Constructivists, and many of the German Bauhaus artists,” a perspective that no doubt de-politicized avant-garde history and that – in a way that was symptomatic of the era’s other art-andtechnology initiatives – conflated technical know-how with avant-garde expectations in a somewhat retro-modernist manner.[6]

Tuchman’s rhetoric echoes that of the influential Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), of which Rauschenberg was a founding partner, an initiative that promised an “organic social revolution” through the art-technology alliance.[7] The authority of initiatives associated with E.A.T. is being renegotiated by critical readings such as Kim West’s in this catalogue, in which he juxtaposes an “oligarchic” ethos with a democratic vision derived partly from the Swedish postwar welfare state and partly from a Russian constructivist tradition. In Anna Lundh’s lecture performances for ”Mud Muses”, E.A.T. is presented as the subject of artistic research and a framework for unfinished history. As she puts it, “what lies in the ‘and’ of ‘art & technology’ now? Not so much focusing on the outcome of the equation, I’m thinking more of this ‘&’ as a fluctuating space in-between, a space where art takes technology as a given, but also takes it seriously enough to be able to question certain conditions that can be tied to technological development and its current (and future) role in societal and environmental change.”[8]

Unlike the institutionalized and corporate exchanges of both A&T and E.A.T., many artistic encounters with technology often were and are self-organized. Apart from reflecting collective forms of production in industry and science, such artistic methodologies also often demand the acquisition of “un-artistic” forms of knowledge such as programming or systems theory. When it acknowledges the ways in which collective intelligence plays out, the artistic thinking of technology often comes packaged with a critique of the individualist ideology of authorship – as testified by the presence in this exhibition of the artists’ groups The Digital Theatre, The Otolith Group, CUSS Group, Primer, Sidsel Meineche Hansen and the Cultural Capital Cooperative, Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas, and the collaboration of collaborations, Soda_Jerk with VNS Matrix.

Moreover, the geopolitics of a North Atlantic axis that has dominated histories of technology and art – including some of those told at Moderna Museet – can be contested by non-Western artist-initiated collaborations.[9] One of these was Mumbai’s Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW), which existed for half a decade around the time of its institutional American counterparts. Initiated in 1969 by the painter Akbar Padamsee and funded partly through a government grant and partly by Padamsee himself, the workshop spurred crossdisciplinary collaboration between painters, printmakers, filmmakers, photographers, sculptors, animators, as well as psychologists. Padamsee writes in his mission statement, “With the advent of electronic technology and cybernetics, a new challenge faces the artist and it is only an exhaustive research into the structure and methodology of communication processes and medias that a new idiom can evolve.”[10] [sic] VIEW evolved as an informal setting that appealed to young artists with its experimental and non-specialized ethos that created “an atmosphere where everyone would come and talk,” as VIEW veteran Udayan Patel puts it.[11] Aimed at creating a new genre of art, participants were expected to transcend media-specificity; Padamsee himself made films, including ”Syzygy” (1969–72), an animation that “explores the relationship between mechanics, physical laws, and biological evolution.”[12] For this “theory towards programming forms”, Padamsee developed more than one thousand drawings composed of numbers, letters, abstract geometric shapes, dots, and dashes that were distributed in a mathematical pattern generated by his own devised code. A kind of algorithmic work, then, that extends modernist abstraction by para-cybernetic means into a dream of numerical play that precedes representation. The films and camera-less photography of Nalini Malani – another VIEW artist who stuck with filmmaking – explore the means and conditions by which social transformation could be represented in post-colonial India. The fierce force of modernity is reflected in how her double projection ”Utopia” (1976) cannibalizes her own abstract architectural reverie ”Dream Houses” (1969), juxtaposing it, in a montage that cuts across less than a decade of rapid development, with dystopian vistas of new urbanization in mid-’70s Mumbai, disenchantedly revealing the naivety of “the Nehruvian dream of building a modern India.”[13] With ”Taboo” (1973), an early feminist statement on the conflict between tradition and modernity, Malani zooms into the social fabric and shows how access to apparatuses of production was gendered in communities of weavers who forbade women to touch the loom because they were considered impure.

In contemporary Scandinavia, the artist group Primer is a further development of ’60s-era exchanges between art and business. In an unusual arrangement, Primer is hosted by a biotech company that develops products for water purification. Unsurprisingly, the division of labour between spheres of interest among artists and engineers are not as distinct as in Rauschenberg’s days, and Primer is attuned to systemic and curatorial thinking rather than to making artworks. Their special case of art’s being-with-business might exemplify a symbiotic or “sympoietic” relation, to borrow Beth Dempster’s cybernetically inspired term that defines a low degree of organizational closure between collectively produced systems, whether natural or cultural: “sympoietic systems are organizationally ajar [and are] evolutionary, distributively controlled, unpredictable, and adaptive.”[14] In Primer’s case, such emphasis on agency across entities that share company and systems, or have allied themselves in co-development, turns artistic process into something porous, a membrane that establishes interdependence with other fields of social invention.

It is a truism that future life on this planet is likely to depend on a positive understanding of togetherness and collaboration. It will also depend on our ability to forge a contact consciousness that sees human culture as inseparable from nature; a being-together as integrated parts of Earth’s larger life-support systems. But such a radical understanding of coexistence must also include synthetic ontologies. In this way, an analysis of “symbiontic” being is incomplete without a perspective on our entanglement with late capitalism’s mechanisms of capture and control.[15] How can we let go of criticality when capital itself makes our nervous systems coextensive with its commodity networks and systems of perception? In the Otolith Group’s ”Anathema” (2011), advanced information technology has come alive to invade and probe human bodies. This is rare imagery of our being-with capital. Featuring television commercials for Liquid Crystal Display systems that are manipulated into abstract synthetic landscapes, the film works over the material substrate of image-borne capital: A sentient being that lends us its eyes and whose dreams we are made to share, but whose spells can perhaps be countered, their libidinal and imaginary charge altered to create new topographies for life and imagination.

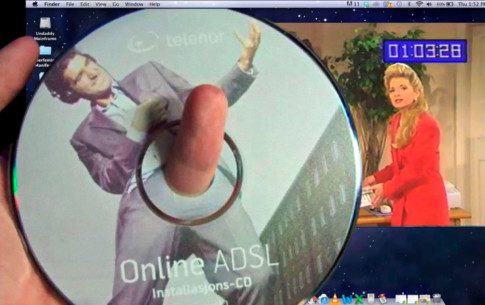

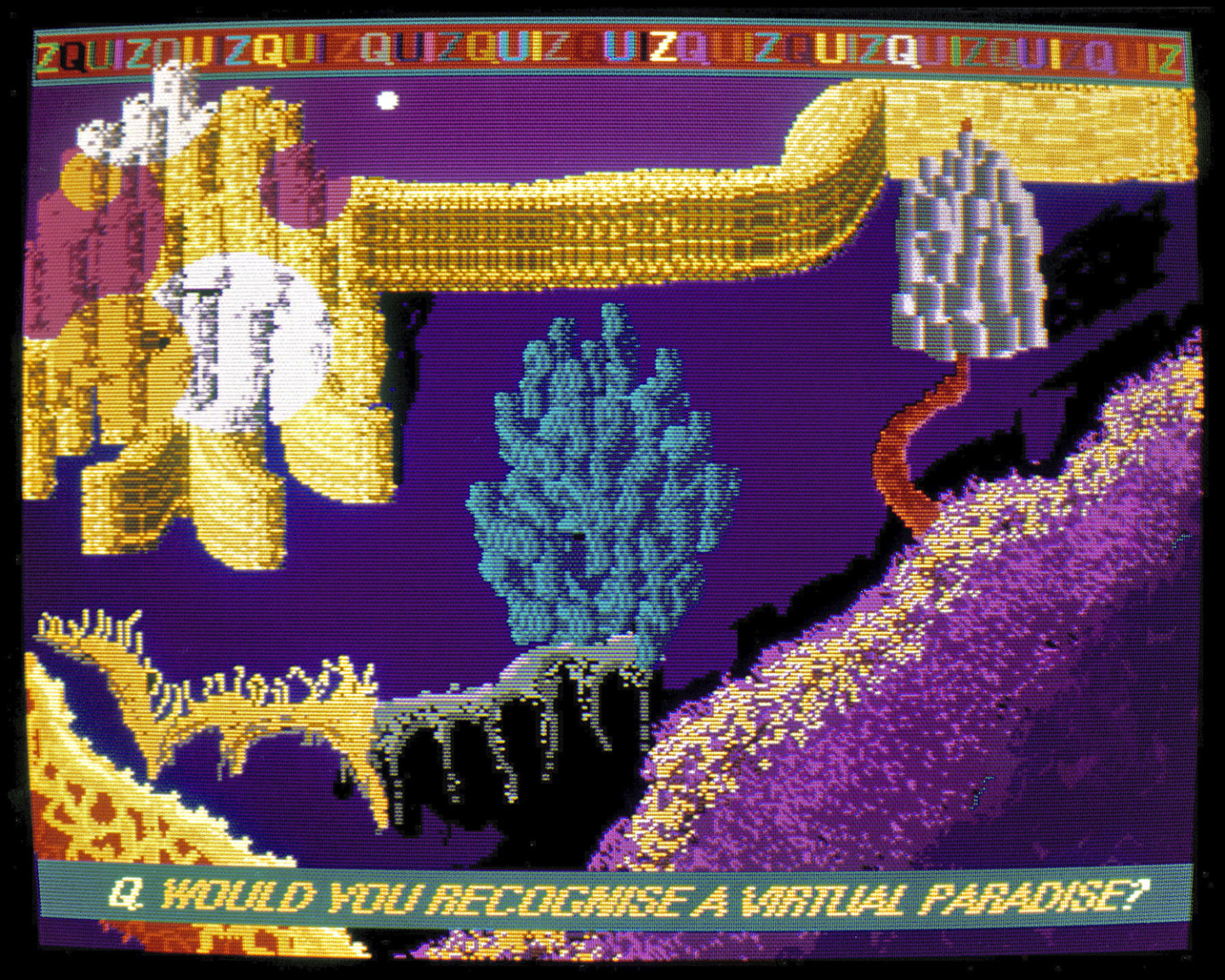

Undaddying the mainframe: beyond techno-patriarchy

”Mud Muse” was presented at Moderna Museet in 1973 in a group show of other American acquisitions and donations. It was received by some local artists and activists with accusations of “technocratic emptiness” and cultural imperialism, a welcome that echoed the often hostile reception in the United States of the ambitious A&T “corporate art” project.[16] These controversies can remind us of how, in our own historical moment, the social tendencies of big data are questioned because of its capacity for disrupting democracy, labor, and equality. Back then, the protesters took Moderna Museet director Pontus Hultén to task for not disclosing the sources of donations and for declining to respond to whether Moderna symbolically condoned the US militaryindustrial complex at the time of the Vietnam War. On his side, Rauschenberg laconically offered that “it is essential that art is considered in industry,” a consideration that at the time was overwhelmingly gendered and racialized, as evidenced by the A&T program’s list of almost exclusively white, male artists.[17]

Anna Sjödahl’s prosaically titled painting ”Centraldatorn i Sundsvall” (The Central Computer in Sundsvall, 1978) [...] suggests the technoscepticism of the decade, rendering the mainframe computer as a totemic sociotope that watches over the population.

Anna Sjödahl’s prosaically titled painting ”Centraldatorn i Sundsvall” (The Central Computer in Sundsvall, 1978) ominously – almost paranoiacally – depicts its cybernetic protagonist by the traditional means of figurative painting and suggests the technoscepticism of the decade, rendering the mainframe computer as a totemic sociotope that watches over the population. Sjödahl’s work has been in the collection of Moderna Museet since 2001 and is exhibited in ”Mud Muses” for the first time.

The gender imbalance of A&T was soon to be subverted. Following their involvement in Malmö’s underground and punk subcultures of the ’60s and ’70s, Charlotte and Sture Johannesson used public and private grants to start Digitalteatern (The Digital Theater), a “microcomputer-based image and audio studio,” and the first of its kind in the Nordic region.[18] The Digital Theatre was a techno-utopian upgrade of the street-theatre groups of the 1960s with the aim to undo perceptual and political dependency on normative structures. During its existence, from 1978 to 1985, its declared mission was to create “micro-performances” with artistic and commercial purpose; for Charlotte Johannesson, the couple’s more artistically productive member during this time, the “micro-performances” turned out to be digital graphics. With a traditional textile-craft education and previous experience producing art tapestries that can best be described as propagandistic, Charlotte Johannesson effectively started The Digital Theatre when she traded her loom for an Apple II Plus (an early milestone in home computing). The fact that she switched from a loom to a computer is a reminder of the fact that the latter is connected to a history of industrial weaving that includes the first punch card-operated mechanical looms in the late eighteenth century. Weaving becomes a mode of “programmed” manufacturing that traverses modernity; at the same time, by connecting one gendered imaging technology to another that is no less but oppositely gendered, Johannesson unexpectedly opened the two to an exchange of aesthetics and procedures and thus linked textile tactility to the coded fabric of digital imagery. “[T]he art world has been consistently unanimous in its refusal to recognize or in any way support computerbased art,” the art theorist Jack Burnham despaired in 1980; the fact that ”Mud Muses” is the first museum presentation of Charlotte Johannesson’s work lends a measure of truth to Burnham’s dark diagnosis. And he wasn’t even thinking about female computer artists.

”Mud Muse” is a system of action as dirty as you want it to be. Rauschenberg – not one to censor himself before using a good visual pun on unstraight sex – initially wanted it to be capable of hedonist audience interaction and had thus conceived of the work “as the perfectly responsive lover,” according to a critic.[19] The artist made no bones about the work’s lack of morality and content, making it clear that it has “no lesson” and no “interesting idea,” understanding it instead to operate on “a basic, sensual level,” with mud that is “light brown in colour and extremely soft to the touch,” as the catalogue helpfully specifies.[20] ”Mud Muse”’s profane mix of “pure waste” and “sophisticated technology,” then, is a libidinal economy that kinkily mediates between the scatological and the eschatological: As we know, technology can be recruited for some shitty purposes, too, such as the optical systems developed by Teledyne for the United States Air Force and employed in the Vietnam War.

In the Adelaide artist group VNS Matrix’s billboard work ”A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century” (1991), Rauschenberg’s installation receives a kindred yet decidedly anti-patriarchal response that features lustful slime secreted by lesbian unicorns. The manifesto integrated into the billboard is credited with being the first use of the term cyberfeminism as a mode of feminist critique of the maleness of instrumental reason and the gendered “neutrality” of technology. As before in the history of social struggles, the manifesto is an inflammatory text that produces political subjectivation by linking a being (woman, in this instance) to a non-being or not-yet-being (woman with a voice, with rights). Thus the collective, struggling to be acknowledged as a political subject, is such a not-yet-being. In the case of ’90s cyberfeminism, whose efforts were activist as well as speculative, real as well as virtual, the collective’s self-determination is also marked by a search for forms of becoming and representation in an unknown, mutating terrain: “Who are we going to be?” as much as “We demand.” VNS Matrix’s pre-post-pornographic battle cry of “making art with our cunts” was appropriated and versioned in 2014 by the equally anonymous Melbourne-based duo Soda_Jerk. Their installation ”Undaddy Mainframe” is both homage to and an extension of the cyberfeminist view of technology as gendered, and gender as technology.

Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s work, alone and together with the Cultural Capital Cooperative, also takes as its point of departure a feminist trope, that of social reproduction. If ’70s-era feminists comprehended the unacknowledged and unremunerated labour carried out by women as wives and mothers, the form and conditions of social reproduction have mutated in a digital regime that turns workers into isolated and self-managing units of production. Here the artist is perhaps the exemplary freelancer and informal worker who constantly must qualify to be able to work. When work is no longer a contractual, formalized relation, it tends toward an encompassing neuro-physicocognitive condition, in the sense that it is the potentials and abilities of the individual subject – creativity, communication skills, the physical ability to carry on – that become the workforce, typically to be picked up and sold through communication technologies and digital devices. One understands, then, why Hansen’s and CCC’s works for the show are lo-fi and un-networked, as they seem to exteriorize transfers of energy that mediate the nervousness of the always performing, always qualifying human subject. The big clay relief ”Cultural Capital Cooperative Object #1” (2016), for instance, looks like a burnt-out flat screen, a non-image of collective traces and petrified immaterial flows.

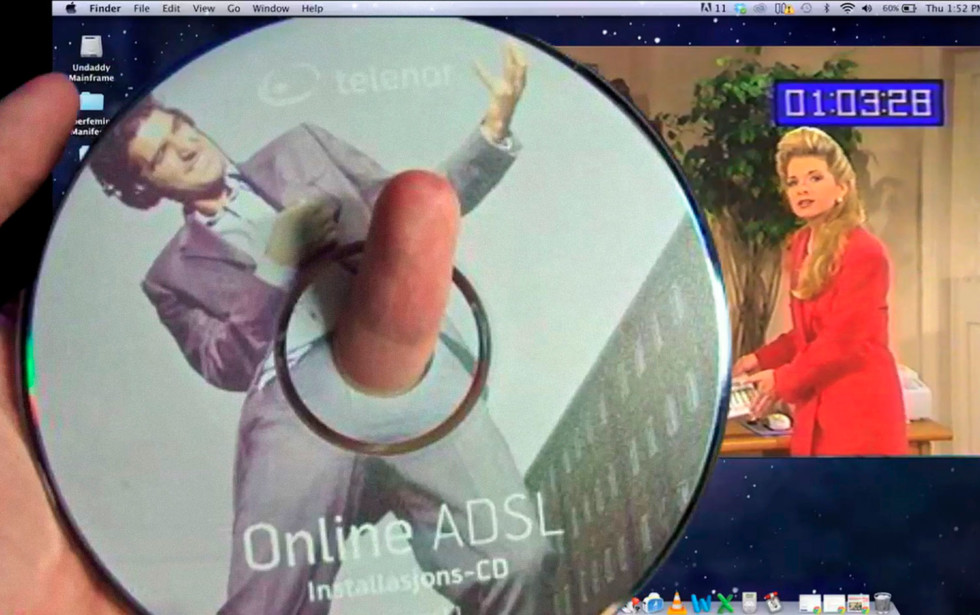

Programmed by Cheng from a computer-game platform and shown on flat screens, the work’s protagonist is a giant worm whose visceral cavorting in a virtual ecosystem is accompanied by munching, shuffling (un)sounds.

The swamp in the temple: museum as artificial mind

If the abject activity of Rauschenberg’s ”Mud Muse” makes for a vanishing point, entropy, is it really the end? Or will a golem or a machine slave rise out of it? Will it be able to play, desire, strike, gesture – or some of the other few things by which humans, when it really comes down to it, can distinguish themselves from artificial intelligences?

”Mud Muse” could have given birth to Ian Cheng’s ”BOB” (short for “Bag of Beliefs”, 2019), like an unwanted side effect slithering out of its tank. This is another one of the exhibition’s few works from Moderna’s collection, and it is no doubt the first artificial life form that has entered the museum’s holdings. Programmed by Cheng from a computer-game platform and shown on flat screens, the work’s protagonist is a giant worm whose visceral cavorting in a virtual ecosystem is accompanied by munching, shuffling (un)sounds. Even as a game that plays out along an infinite duration – what Cheng calls “a live simulation” – ”BOB” is not entirely autopoietic, that is, creating itself from itself, as the cybernetic term goes: you can interact with it through an app. However, interactivity is not a given, as viewers will need to find a wormhole through to ”BOB”’s parallel realm to stimulate this digital organism, which will never stay the same nor turn into a butterfly.

In his ”Art and Agency” (1998), anthropologist Alfred Gell writes of how the “possession of ‘significant interiors’ is a very common feature of sculptural works specifically intended for cult use,” and thus a crosscultural commonality by which actions of social others can be interpreted in terms of a “ghost in the machine.”[21] This means that as a result of seeing external, physical behaviours as caused by internal, animating forces, many societies have activated their idols by providing them with layers or interior spaces, or by marking distinctions between surface and depth: “Holes or cavities (themselves filled with animating substances) may be drilled into the ‘idol’s body.’”[22] This animating strategy is conveyed by spatial modelling, then, not resemblance, turning idols into “(artefactual) bodies,” and, one understands, possessing artificial minds.[23]

Both Cheng’s ”BOB” and Rauschenberg’s ”Mud Muse” can be understood as concentric idols; and both make for artificial minds that, with glee and sludge, deconstruct any mindmatter dualism and related hierarchical ordering. Jenna Sutela’s contribution to the show – a new commission – can also be comprehended by this logic, as she demonstrates that a technology and the visions it can enable are two different things. Having had glass containers for lava lamps cast in the likeness of her own head, Sutela builds a media archaeology between a “low” medium of the “high” ’60s and twenty-firstcentury artificial neural networks in her ”I Magma” (2019). The lava lamp visualizes, in its own domesticated way, the poetics of magma: The idea of a hidden, primeval flow of life and a transformative flow of the imagination. Sutela’s psychedelic selfportraits are hooked by live video feeds to a machine-learning program that, via an app, looks for patterns and signs in the lamps with code from the ”I-Ching”, or ”Book of Changes”; with input from the movement of the hot, coloured goo inside the heads, the computer produces divinations. Consciousness and symbolic meaning are suspended between signal and noise in a magmatic fantasy of pure potential that threatens to undo who we are as humans, and what we know.[24]

The logic that Gell identified with his concentric idols extends to the built environment, too, through boxes and arks to sanctuaries and temples. The idols, Gell writes, “come to stand for ‘mind’ and interiority … by becoming the animating ‘minds’ of the huge, busy, and awe-inspiring temple complex.”[25] A concentric idol signifies outward – in our case to the home of the muses, the museum. It is not only through Moderna Museet’s exhibition history, though, with ”Movement in Art” (1961) or the 1968 exhibition of Vladimir Tatlin, that the institution related to a machinic imagination: Cybernetic thinking was also implied in the museum’s attempts to reconfigure what can be called the exhibition apparatus itself.[26]

A concentric model was used in a diagram (see pp. 77) drawn during the mid-’60s by Hultén and curator Pär Stolpe. It outlines the modern museum as a spherical institution consisting of four layers. The outermost layer “connects to the universe of everyday life … characterized by an accelerated concentration of information.” The second layer is reserved for workshops in which the “means of production are available” to be used by museumgoers. The third layer of the sphere will present the productions of the workshops in “different manifestations: visual arts, films, photo, dance, concerts….” The final layer, the core, is to contain the memory of the processed information, the museum’s collection.[27] In Kim West’s summary, the information-centre model’s vision of a future modern art museum would never be realized in Stockholm but can be followed to Hultén’s work during the ‘70s as the founding director of the Centre Pompidou. The concentric diagram is suggestive of how the art-technology nexus challenges the physical space and isolationist ideology of the modernist art gallery’s “white cube,” reconceiving it as a databank and transmission station that should be opened up to the social field. For ”Mud Muses”, exhibition architects Kooperative für Darstellungspolitik’s concept of placing the presentations within a grid reflects a similar emphasis on art’s space as a medium: Derived from the museum’s architecture, the grid becomes an abstract yet site-specific machine, or, in their own words, an “antihierarchical diagram” for the placement of artworks and the interaction among themselves and with the audience.

Lucy Siyao Liu creates a historic arc in which the cloud – this amorphous, impalpable manifestation of the material world – comes to exemplify how technology, in a radical sense, has become elemental at our point in history.

Lucy Siyao Liu’s ”A Curriculum on the Fabrication of Clouds” (2019) is another project developed for ”Mud Muses”, one that enters into dialogue with the museum by activating the deep time of art history. ”Curriculum” takes the form of a spatial montage that mixes cloud depictions by canonical artists such as John Robert Cozens and John Constable with scientific diagrams and Liu’s own drawings and animations. She creates a historic arc in which the cloud – this amorphous, impalpable manifestation of the material world – comes to exemplify how technology, in a radical sense, has become elemental at our point in history. Above Rauschenberg’s synthetic mud, Siyao Liu’s cloud compendium: At the nebulous limit shared by nature and culture, elusive forms chase emergent meaning. By showing human models and dynamic systems as historically and environmentally contingent, ”Curriculum” liberates the cloud from its contemporary signification as data infrastructure.

Cosmotechnics, or the Disappearance of the Modern Human Being

Mud is alien and archaic. It is found at the beginning and at the end of times, and where humanity both strengthens and misplaces its grip on history.[28] Rauschenberg’s ”Mud Muse” takes the lid off technology’s black box to reveal the longue durée of the primordial soup, or an incontinent artificial mind capable of tracing historic continuities and of making cultural comparisons.

Today, due to external and internal pressures, historical space seems to be foreshortening in different ways and – for better or worse – bringing concepts and practices into close contact that were once segregated by modernity. As Esther Leslie characterizes our epoch, it is “an age of turbidity” that compresses modern and a-modern tendencies, insides and outsides, the rational and the irrational, and other binaries once established to keep the human subject autonomous and sovereign. It is in these dim regions that Suzanne Treister has long deployed her work, of which the exhibition presents selections from across three decades. Treister presents claims of technology’s rationality as only skin deep: Just beneath its surface we find metaphysical subtleties and augmented reality of an analogue sort. In her games and mappings, technology becomes an exemplary battleground of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s dialectic of the Enlightenment, an analytic in which the rationalized, modern world order paradoxically produces irrationality and barbarism. Tellingly, Treister is a new-media pioneer who remains sceptical of new media, instead working with counterintuitive artistic means to rewire and explore our beliefs in tech, such as the ritualized information architectures of the tarot deck and the cosmogram. From the other side of instrumental reason, she dramatizes how networked digital information technology and their prowling algorithms require us to master arcane bodies of knowledge that we barely understand, within elaborate infrastructures that are ordinarily invisible to us.

Instead of techné in its classical and domesticated sense of mechanics and knowledge, it seems apposite to now consider the cosmopolitical implications of the ways in which technology produces time and space. In more than one sense, cosmos is where the modern human being disappears: Cosmologies tell the beginnings and ends of worlds, and they straddle concepts and knowledge forms that the western mind otherwise likes to keep apart, such as science and religion, or nature and culture. With humankind’s geological impact on Earth’s ecosystems, you can no longer distinguish between anthropological and cosmological orders the way one did in the modern era.[29] Philosopher Yuk Hui proposes that the view of nature of our time is as a third nature: neither a nature understood to exist for itself (as in the romantic era), nor a nature framed and dominated by technological reason (as in modernity), but instead a nature that exists in a continuum with a world view that necessarily incorporates technology, a “cosmotechnics.”[30]

When resources are scarce or unavailable, the human subject becomes frail: how and from what will the power come to light our screens, ensure our mobility, keep us fed? Two projects in the exhibition deal with the energy question under a cosmotechnical continuum. In CUSS Group’s new work, ”Kumnyama la / It’s Dark Here” (2019), the functioning of the local technosphere is shown to be anything but transparent and predictable. Due to an unstable utility supply and frequent power cuts, Johannesburg citizens in underprivileged areas of the city often tap electricity off of the grid. This dangerous and illegal practice is handled by Izinyoka, Zulu for “snake,” a slang term given a further dimension when the electricity company adopted it in demonizing official warnings.[31] Thus as “snake-men” operate in an urban context still defined by Apartheid-era policies, and that now is at the same time an experimental zone for a new African high-tech economy, popular as well as institutional responses to unreliable infrastructure extend technology’s civic scale through unexpected social imaginaries: In the dysfunctional city with a contradictory and densely layered history, fragmented common experience becomes a battleground for everyday mythology that reflects social power structures.

As a part of their applied and speculative research into mixed technologies, Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas look to the capacity of mushroom and mud bacteria to generate electricity in batteries. In general, fungi are useful for testing established systems: knowledge systems; classifications and intellectual categories; and the modern constitution that rests on the human ability to distinguish between realms of being – as well as, potentially, for testing new energy systems for an ecologically disturbed planet. As fungi exist both inside and outside of us, and before and likely after humans, too, the mushroom’s perspective refuses to acknowledge the human limit to the environment. With their personal background in the “mycophile” – fungiloving – culture of Eastern Europe, and with reference to authors such as J.G. Ballard and the Strugatsky brothers, the Urbonases’ fungi-tech encourages a science-fictional approach to artistic research that attunes human contact consciousness: In sum, we must re-envision technology as something radically different from the human victory over nature.

Technomythologies: Being-in-Debt

Anthropologist Roy Wagner argues that what we call mythology is a discourse about the given – primordial conditions from and against which something or someone will be defined or constructed. Myths are discourses that establish the terms and limits of an ontological debt, then: that to which you owe your existence. Following this, a Western myth of new technology would imply how we are indebted to it for our way of life. New technology demands that we adapt, for instance: supposedly we owe it to carry out the required changes in ourselves. This lack in being creates a particular dynamic for technology that confusingly allows it to be both here and there, even as it is seen as the cause of linearity, efficiency, and progress. Thus its capacity for revolutionizing production and social processes places it at the centre of human history, while at the same time it is considered to be in excess of this history by supposedly allowing us to surpass ourselves by pulling us into the future through constant cycles of obsolescence and upgrade. And we have made a profound mess of this planet by making extraction-dependent technologies emblematic of progress, even if their tacit premises were the exploitation and destruction of ecosystems – but luckily new technologies can fix all that, with the ideological leverage to perform a Baron von Münchhausen-style manoeuvre with which we can pull ourselves out of the mud by our collective ponytail.

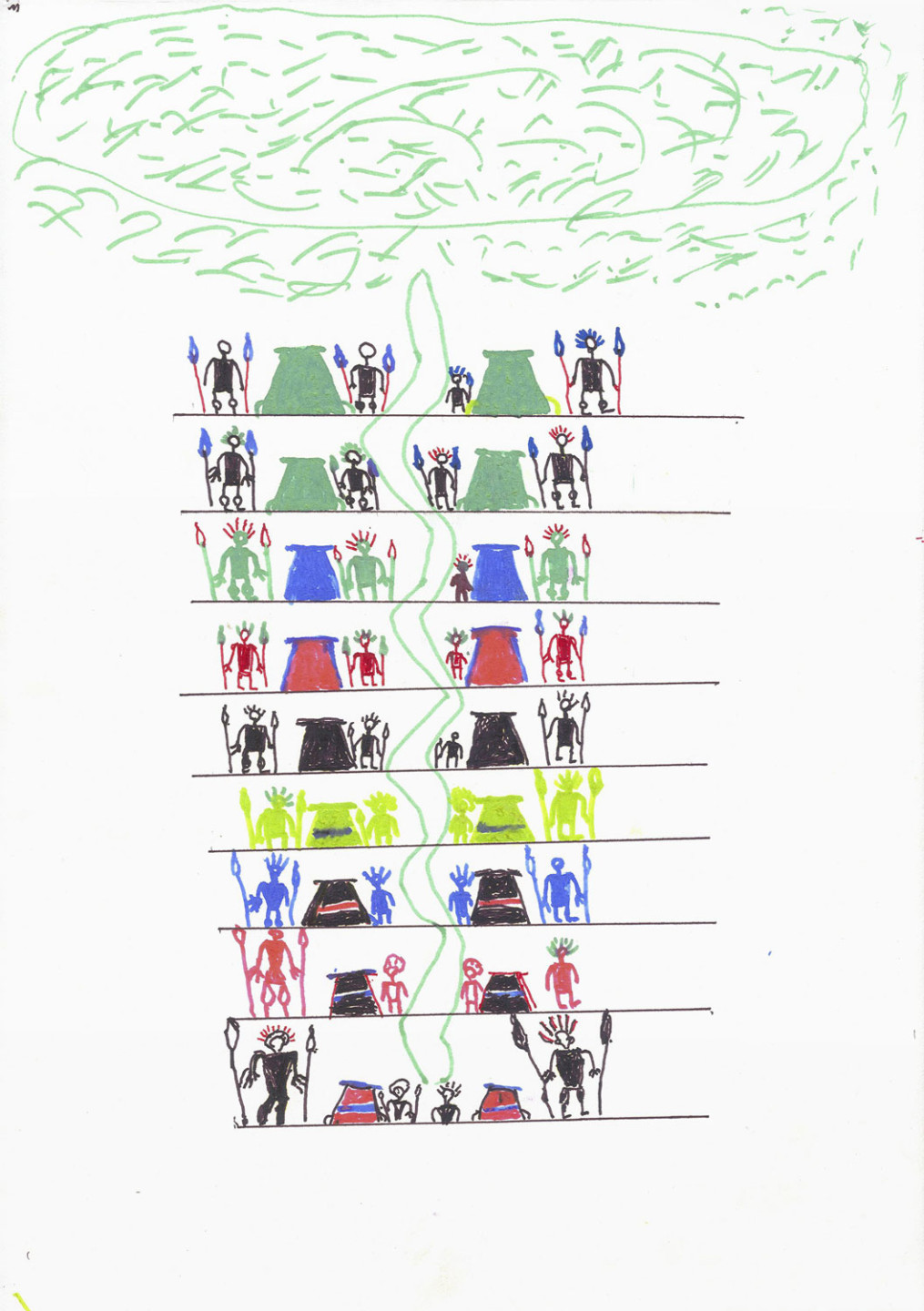

The drawings are cosmograms of Marubo mythology. Importantly, the drawings are no original Indigenous artefact – Marubo mythology is an oral tradition – but a means of communication derived from the meeting of two cultures.

What Jack Burnham called “technology’s mythic consistency” also has the cultural effect of undoing the being of the “other.”[32] Technology can be an exclusionary concept when it is understood to augment certain cultures and make them superior to notionally un-progressed ones, thereby annulling the possibility of co-existence. In this way, first-nations peoples are typically excluded by and from conventional Western concepts of technology that consider them backwards, which is a salient point in a decolonial critique of the concept of technology. ”Mud Muses” presents a series of drawings by Armando Mariano Marubo, Paulino Joaquim Marubo, and Antônio Brasil Marubo, three shamans of the Marubo, an Amerindian tribe; collected by the anthropologist Pedro de Niemeyer Cesarino, the drawings are cosmograms of Marubo mythology. Importantly, the drawings are no original Indigenous artefact – Marubo mythology is an oral tradition – but a means of communication derived from the meeting of two cultures as represented by the shamans and Cesarino. From their liminal perspective, then, the cosmograms tell the story not only of Marubo myth but also of its renewal. As Cesarino points out, these pictographic compositions are based on a virtual technology of formulaic structures, visualizing what is collectively imagined every time a myth has been retold. Considering this, perhaps we can propose additional meanings of the term cosmotechnics: How do you truly measure a technology if not by its effects on society, culture, and ecosystems? What are the finest things, technological objects or the web of life of which they are part? Such a perspective might help displace accusations of primitivism. What are the means by which we, to borrow from the Marubo, hang the sky?

Armando, Paulino, and Antônio Marubo are not the only non-artists in the show to work with cosmograms. In 1971, Branko Petrović (1922–1975), an architect from Zagreb, wrote ”Systematization of the Human Environment” to address, somewhat rantingly, “completeness and complexity – from material to immaterial, from physical to psychical, from function to abstraction, from present to futurological forms, from reality to phantasy and imagination.” This was at a time when, as the art historian Nikola Bojić explains, the future became in different ways “a methodological issue”: The first computergenerated forecasts of a far-reaching environmental collapse were made, and the Non-Aligned Movement, founded in 1955 by Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Yugoslav president Josip Tito, contested Cold War power formations to create a non-imperialist future.[33] In a distinctly speculative take on the cybernetic concern with evolving and adaptive systems – a speculation versioned in the context of Socialist Yugoslavia – Petrović drew diagrams of environments comprehensively interpenetrated by all sorts of media: Spatial and urban media, socio-media, psycho-, naturo-, and techno-media, all as subject to “spherical curves of time rhythms.” Pushed to the edge of such dizzying mediality, the human subject re-emerges as homo effluviens. The pathetic, disfigured (hu)man of flows is at odds with the anthropocentric formula of Le Guin’s view of technology as “the active human interface with the material world.” This suspicion is also raised by other artworks in the show: as the interface of technology might turn out to be more active than human, its mediations of the material world can be expected to loop back and act on humanity in ways that will provoke shifts in protocols for our behavior and unsettle received ideas of our speciesbeing. Petrović’s esoteric-looking maps of a globally integrated future technosphere were originally created as a contribution to the 1972 UN conference on the environment in Stockholm: for unknown, but likely political, reasons they were not presented here then, and his work arrives in Sweden with a delay of half a century.

… To the Next Transformation

For better or worse, the globalized West finds itself increasingly confronted with the limitations or even breakdowns of the certainties that brought us to the present. These include the notion of the pure functionality of our machines and our preconceptions about their place in the world. Much of what we call technology is premised on being so easy to use that you shouldn’t need to think about it, because truly understanding it is only for experts: A premise that prevents conscious evaluation of our everyday interaction with it.

By bringing media and apparatuses within perceptual and conceptual reach, art offers means to stimulate our techno-literacy and reconnect tech to material experience. Art’s open-ended relation with technology shows that the latter’s production of time and space always gives us something more than what we bargained and thought we had accounted for: Excesses, bubbles and spills that can be folded, stretched, and reconstructed in the art-technology nexus. Thus behind art’s interruptions of ordinary functionality there is typically the simple question: ‘what makes this work?’ – not only on the level of engineering, but also in terms of the convictions, norms, and power arrangements that invent and sanction a given function. Everyone, not only artists, is entitled to ask this question, in order to raise the social and ethical problems that technical solutions cannot adequately address.

The next transformation must be a great, almost unimaginable one.

References

[1] See, for instance, Jack Burnham, “Art and Technology: The Panacea That Failed” (1980) (https://monoskop.org/images/4/4e/Burnham_Jack_1980_Art_and_Technology_The_Panacea_That_Failed.pdf, last accessed August 7, 2019), and Charlotte Johannesson’s discussion in this catalogue of how it was seen as a faux pas for the engagée artist to work with computers in the 1970s.

[2] I am mixing Peter K. Haff’s notion of the technosphere with Adam Greenfield, ”Radical Technologies. The Design of Everyday Life”, London: Verso, 2018, p. 6. Greenfield writes, “Networked digital information technology looms ever larger in all parts of our lives. It shapes our perceptions, conditions the choices available to us, and remakes our experience of space and time.… It even inhibits our ability to think meaningfully about the future, tending to reframe any conversation about the reality we want to live in as a choice between varying shades of technological development” (op. cit., p. 8).

[3] In other words, it is important to consider the historicity of the art-technology juxtaposition to avoid concealing or disarticulating the fact that technologies, and the question of technology, have always been present in art making and in the cultural rationalizations of art.

[4] “Unsounds” is Steve Goodman’s term for sonic matter that is “suspect, unsavoury, or ignores rules and norms.” Steve Goodman, ”Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear”, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010, p. 9.

[5] To Rauschenberg, ”Mud Muse” built associatively on naturally occurring sludge fountains at Yellowstone National Park: so-called “paint pots” in which rising gases and thermal heat drive strongly coloured mud out of the earth. Within his own production, he relates ”Mud Muse” to the “earth paintings” from the 1950s. But the aesthetic and perceptual transvaluations performed by the work go beyond media specificity. We can allow ”Mud Muse” to depart for a post-medial and interdisciplinary hermeneutic framework via Leo Steinberg’s concept of the flatbed picture plane, with which he proposed to characterize much 1960s painting: Steinberg borrowed the term from the flatbed printing press that prefigures the flatbed scanners and embedded technologies at our end of history.

[6] Maurice Tuchman, “Introduction,” Maurice Tuchman (ed.), ”A Report on the Art & Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967–1971”, Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1971, p. 9. Tuchman curated A&T with Jane Livingston.

[7] Quoted from Matthew Wisnioski, ”Engineers for Change: Competing Visions of Technology in 1960s America”, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012, p. 143.

[8] Interview with Anna Lundh, p. 209 in this catalogue.

[9] E.A.T. is a part of Moderna Museet’s formative “laboratory years” during the first decades of the museum’s existence: the project was present, for instance, in the exhibition ”Utopia and Visions, 1871–1981” (1971) and initiated ”New York Collection for Stockholm” (1973). Pontus Hultén’s Museum of Modern Art exhibition ”The Machine: As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age” (1968) and his close connection with E.A.T. president Billy Klüver are also part of this “New York connection” (see Hultén, “The New York Connection,” in Lundestam [ed.], ”Teknologi för livet. Om Experiments in Art and Technology”, Norrköping, Sweden: Norrköpings Konstmuseum, 2004, pp. 143–148). In the same era, the museum also famously presented exhibitions about Russian constructivism (such as the Vladimir Tatlin exhibition in 1968), the interdisciplinary project ”Ararat” (1976), and an avant-garde genealogy of kinetic art (”Movement in Art”, 1961).

[10] Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship Booklet, New Delhi, 1969, p. 8.

[11] Laurent Bregeat: unpublished video interview with Patel, 2009.

[12] Nancy Adajania, “Registers of Participation: Two Cultural Experiments with the Contemporary in 1960s India,” in Georg Schöllhammer and Ruben Arevshatyan, ”Sweet Sixties: Specters and Spirits of a Parallel Avant-Garde”, Cambridge, MA and Berlin: MIT Press and Sternberg Press, 2014, pp. 92–106. ”Syzygy” is the only of Padamsee’s two films from the VIEW era that still exists; the subsequent ”Events in a Cloud Chamber” has been lost. In his wonderful, eponymous short film from 2016, Ashim Ahluwalia documents and dramatizes this loss.

[13] See the conversation with Nalini Malani in this catalogue, p. 320.

[14] 14. Beth Dempster, “Sympoietic and Autopoietic Systems: A New Distinction for Self-organizing Systems,” at http://www.isss.org/2000meet/papers/20133.pdf (last accessed June 17, 2019).

[15] I am borrowing Caroline A. Jones’s portmanteau from her unpublished manuscript “Sensing Symbiontics, or, Being with Archaeo-Bacteria” for the Concordia University Hexagram lecture, May 3, 2018, p. 9.

[16] Kim West, ”The Exhibitionary Complex: Exhibition, Apparatus, and Media from Kulturhuset to the Centre Pompidou, 1963–1977”, PhD dissertation, Södertörns Högskola, 2017, p. 240; see also Burnham, op. cit., for a brief summary of his own and Max Kozloff’s ”Artforum” reviews of the exhibition.

[17] Tuchman, op. cit., p. 285. Every artist in the ”Art & Technology” program, except Channa Davis and Aleksandra Kasuba, were male, and the lineup was a mix of European and (mainly North) American artists: Max Bill, Öyvind Fahlström, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Jean Dubuffet, Michael Asher, and Andy Warhol, among others.

[18] Quote from promotional material for The Digital Theatre, 1981.

[19] Tuchman, op. cit., p. 285.

[20] Tuchman, op. cit., pp. 282, 285, and 286.

[21] Alfred Gell, ”Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory”, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1998, pp. 127 and 141.

[22] Quoting Byron Ellsworth Hamann, “An Artificial Mind in Mexico City (Autumn 1559),” ”Grey Room 67”, Spring 2017, pp. 6–44.

[23] Gell, op. cit., p. 98.

[24] Early experimentation on ”Mud Muse” between Rauschenberg and the team of Teledyne engineers points in a psychedelic direction by including ideas about a hallucination-inducing lowfrequency sound tunnel and a machine that could transubstantiate metal between a molten, liquid state and solid form.

[25] Op. cit., p. 136.

[26] This idea comes from Kim West’s dissertation.

[27] West, op. cit., p. 8.

[28] Theory attuned to messy entwinements is now catching up to our historic predicament, such as urban theorist Shannon Mattern’s recent history of five thousand years of urban media. Here she dives into civilizations’ material substrates of mud and its material analogues clay, stone, brick, and concrete, which “have supplied the foundations for our human settlements and forms of symbolic communication,” thus binding together “our media, urban, architectural and environmental histories.” Shannon Mattern, ”Code and Clay, Data and Dirt: Five Thousand Years of Urban Media”, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017, pp. 88 and 113.

[29] See, for instance, Edoardo Viveiros de Castro and Déborah Danowski, ”Ha mundo por vir? Ensaio sobre os medos e os fins”, Florianópolis, Brazil: Editora Cultura e Barbárie, 2014.

[30] Yuk Hui, ”Recursivity and Contingency”, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2019, p. 1.

[31] “Izinyoka” is derived from the slang term “Izinyokanyoka” which was created by the disaffected communities to describe the snaking cables on the ground. The term was then adopted by the electricity company which used the term to personify and demonize the imagined “snakemen”. The title ”Kumnyama la/It’s Dark Here” is a blend of Zulu and English.

[32] Burnham bases his use of mythology on Roland Barthes’s ”Mythologies” (1957) and on religious or mystical experience.

[33] Nikola Bojić, ”Anthroposcenarium: A Study by Branko Petrović, 1971”, unpublished manuscript, 2018, p. 1.

Lars Bang Larsen

Lars Bang Larsen is a writer, teacher, and art historian, and adjunct curator of international art at Moderna Museet. He has (co-)curated exhibitions such as ”Dierk Schmidt: Guilt and Debts” (Reina Sofía, 2018), ”Incerteza Viva”, the 2016 Bienal de São Paulo; and ”Georgiana Houghton: Spirit Drawings” (Courtauld Gallery, 2016).

He is author of ”The Model. A Model For a Qualitative Society 1968” (2010), ”Networks” (2014) and ”Arte y Norma” (2016), among other books and catalogues. His PhD from 2011, ”A History of Irritated Material”, focuses on the geopolitics and transformations of the concept of psychedelia, and its relation to artistic production in the post-World War II era.

Buy the exhibition catalogue

This essay by Lars Bang Larsens is featured in the catalogue together with texts and interviews by Nicola Bojić, Rhea Dall, Olle Eriksson, Mark Fisher, Yuk Hui, Olle Kåks, Ursula K. Le Guin, Esther Leslie, Jordan Rain Matthiass, Pedro de Niemeyer Cesarino and Kim West.