Robert Rauschenberg, Mud Muse, 1968–1971 Photo: Prallan Allsten/Moderna Museet © Robert Rauschenberg / Untitled Press, Inc. / Bildupphovsrätt 2018

Participating artists in Mud Muses

Ian Cheng

”BOB” (2018)

With the newly acquired work BOB, short for ”Bag of Beliefs”, Moderna Museet’s collection has been enriched with its first artificial life form. The work’s protagonist, BOB, was programmed by Ian Cheng based on a gaming platform. The large worm-like being slithers around in a virtual eco system accompanied by a munching, dragging sound. In constant motion, it assumes different shapes. BOB comes close to what is called “autopoietic” in cybernetics, that is to say, self-producing. Via an app, visitors can give gifts and interact with BOB, who can incorporate inf luences and is able to learn from experience – like humans, BOB seems to seek stability yet long for small disturbances in everyday life. BOB can also die and be reborn. The artist argues that the cyclical element highlights the immortal characteristics in BOB, which live on, beyond the viewer’s scrutiny and entire existence. Although the being partially interacts with its surroundings, Ian Cheng points out that BOB isn’t just interactive art but also art with an internal nervous system.

CUSS group

(Jamal Nxedlana, Chris McMichael, Lex Trickett, Zamani Xolo, Ravi Govender): ”Kumnyama la/It’s Dark Here ” (2019)

CUSS is a collective artistic platform based in Johannesburg that runs projects related to burning issues in South Africa. In its work for ”Mud Muses”, CUSS shows how the housing structures in Johannesburg are emblematic of a failure in which the state, three decades after apartheid, has not succeeded in liberating itself from colonial thinking. The poor are still relegated to substandard housing on the periphery of the city. The sand refers to how the black population was forced to live near mine dumps where chemical sludge and irradiated waste still cause problems today. The tangle of cables represents a situation where people take matters into their own hands and connect directly to the city’s electricity grid, a dangerous and illegal operation performed by so-called izinyoka, “snakes” in Zulu. In the government’s anti-izinyoka campaigns, people are depicted as snakes that commit their evil deeds under the cover of darkness. Communicating using the demons of folklore obscures the fact that the situation is more about inadequate infrastructure and politics than monsters. The dysfunctional city becomes a battleground for a kind of everyday mythology.

Sidsel Meineche Hansen & Cultural Capital Cooperative

Sidsel Meineche Hansen

”Employee” (2019) and ”Freelance” (2019)

Cultural Capital Cooperative

”Cultural Capital Cooperative Object #1” (Un-authored, 2016)

”Cultural Capital Cooperative Object #2” (Nikita Gale, Candice Lin, Nour Mobarak, Blaine O’Neill, Patrick Staff, 2016)

Reflecting conditions of labour and remuneration in the era of digitalisation, the works of Cultural Capital Cooperative are copies of existing art works that are created collaboratively and based on cooperative ownership. The clay relief ”CULTURAL CAPITAL COOPERATIVE OBJECT #1” (”CCCO#1”) versions a ceramic interior design by Danish artist Asger Jorn (1914–1973). Carrying indelible, physical marks of its production, ”CCCO #1” looks like a burnt-out body or a solidified flatscreen that carries imprints of collective labour. For the single-channel video ”CCCO #2”, the cooperative remade Shigeru Izumiya’s horror film ”Death Powder” (1986). According to the group’s rules of production, the work should be executed during one day of shooting on phone cameras, and body horror was to be elaborated as a theme resonating with the social conflicts of contemporary politics, such as Brexit and the 2016 United States presidential election.

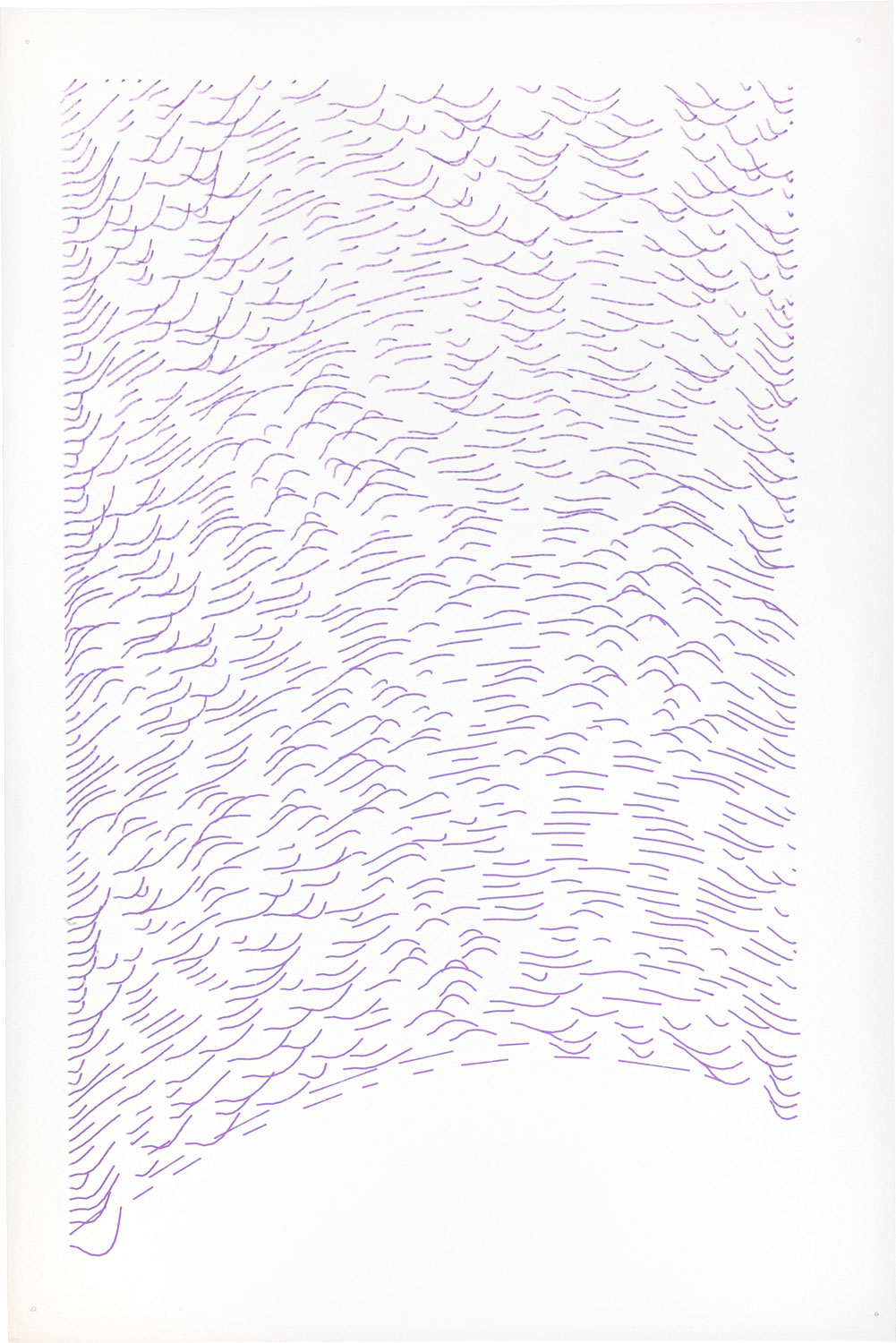

Hansen’s laser woodcuts ”Employee” and ”Freelance” (2013/2019) revolve around ways in which labour power is mediated into different economic arrangements through manual, cognitive and automated work processes. Initially drawn by hand, the drawings were tracked in a graphics program in order for the laser cutter to read the drawing and cut it into wood. Hansen understands this procedure as a feminist appropriation of Edvard Munch’s expressionist woodcuts: instead of taking her point of departure in artistic subjectivity and its psychological space, she directs her work toward the social, economic, and political conditions that render contemporary life precarious.

Charlotte Johannesson

Textiles and digital graphics (ca. 1970–1986)

Charlotte Johannesson has a background in traditional textile craft but decided in the late 1960s to make art. Her tapestries from the following years can best be described as a kind of textile punk, taking inspiration from the Swedish-Norwegian artist Hannah Ryggen’s (1894–1970) satirical works, among other sources. In 1978, Johannesson traded her loom for an Apple II Plus, one of the very first home computers. Charlotte and her partner Sture Johannesson (1935–2018) founded and ran The Digital Theater in Malmö, a microcomputer-based image and audio studio that existed from 1978 to 1985 – the first of its kind in Scandinavia. Here Charlotte Johannesson turned to digital graphics, with which she channelled contemporary image worlds and technological im-aginaries. Neither the loom nor the computer were necessarily considered very artistic media at the time. Going from the loom to the computer meant an exchange between analogue and digital, thread and code, and the histories and sensibilities linking the two technologies.

Lucy Siyao Liu

”A Curriculum on the Fabrication of Clouds” (2019)

Lucy Siyao Liu’s contribution, which was specially made for ”Mud Muses”, is a meditation on how the nebulous un-form of the cloud became linked to algorithmic thinking. The installation is a “thinking space” that mixes cloud depictions by nineteenth-century artists such as George Sand and John Constable with scientific diagrams and the artist’s drawings and animations. Before clouds disintegrated into a symbol for dynamic systems, artists and scientists gathered information on these amorphous objects with the technologies at hand, whether drawing, photography, or human memory. ”A Curriculum on the Fabrication of Clouds” activates art history to give a different perspective on our technological present, where the idea of “cloud” has become closely associated with digital infrastructures and the unseen presence of data. Cloud in contemporary discourse is rarely a cloud, Liu argues, as it is so frequently cited as a model of coherence in design that it has become a trope shape of the 21st century. Perhaps it is a symptom of how networked technologies have become “natural”.

Anna Lundh

”Towards Disorder/Visions of the Now” (2019)

Anna Lundh’s lecture performances for ”Mud Muses” are part of the artist’s research project on the history of the influential association Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), of which Robert Rauschenberg was a founding partner in 1967. E.A.T. was a part of Moderna Museet’s early experimental period and participated in exhibitions such as ”Utopia & Visions 1871–1981” (1971). The organisation’s chairman, the Swedish-American Billy Klüver (1927–2004), was also one of the instigators of ”New York Collection for Stockholm” (1973), where Rauschenberg’s ”Mud Muse” was shown for the first time at Moderna Museet.

To Lundh, E.A.T. becomes the framework for an unfinished history. She is interested in what the “and” in Art and Technology stands for today and suggests that it is a fluctuating space in-between, a space where art takes technology as a given but also offers a space to question and challenge it.

Read more about Lundh’s lecture performances: Towards Disorder/Visions of the Now

Paulino Joaquim Marubo, Armando Mariano Marubo and Antônio Brasil Marubo

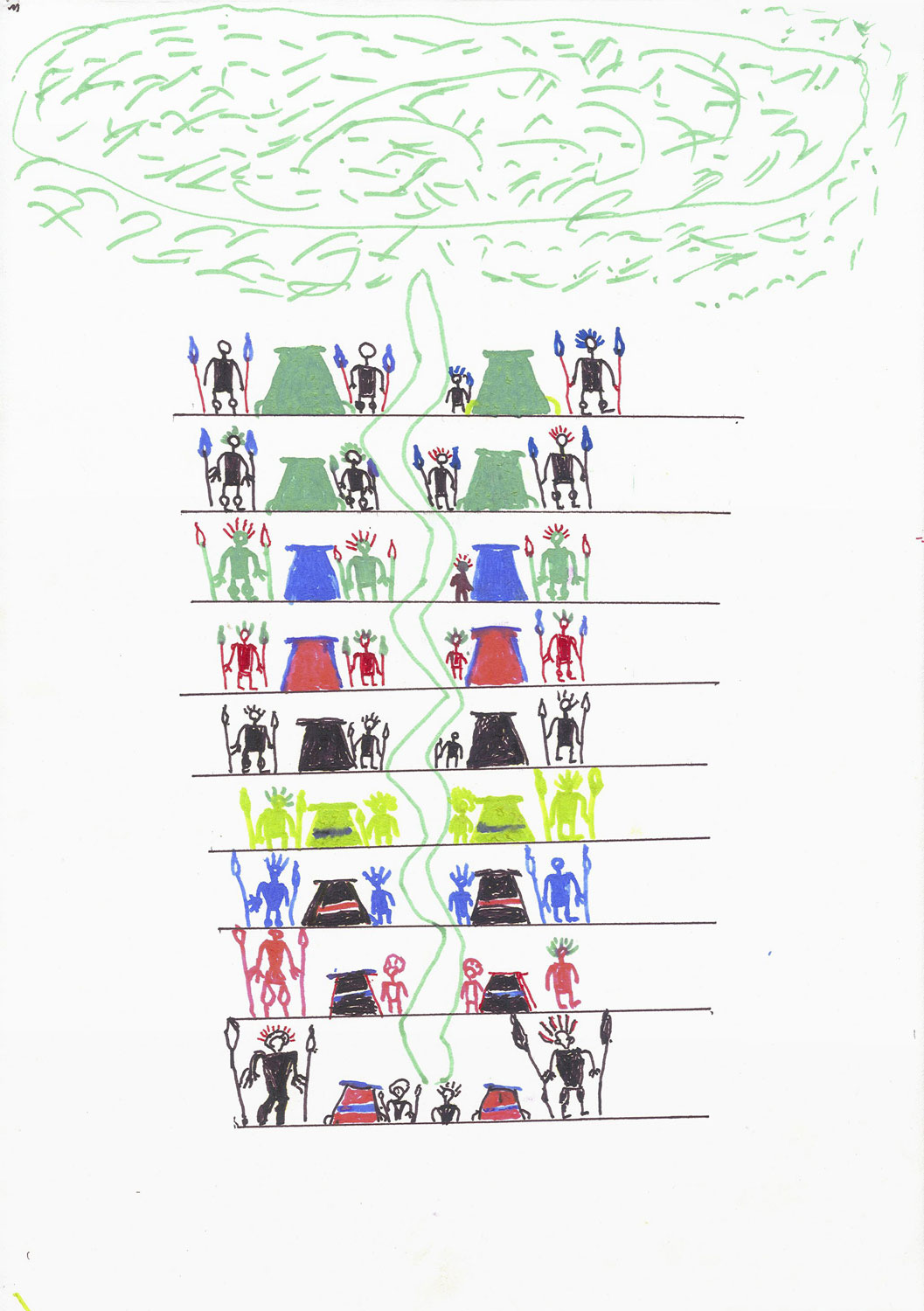

”Cosmograms” (2004–2009)

These sixty drawings are by Marubo shamans from the Amazon in Brazil and were collected by the anthropologist Pedro de Niemeyer Cesarino. Marubo mythology is passed on via an oral tradition consisting of songs and stories that are constantly evolving in content and form. Paulino, Armando, and Antônio Marubo have transferred myths and cosmological knowledge to paper; the drawings can be seen as an attempt at communication between two cultures. Cosmographic schemes and narrative sequences are expressed in a symbolic language based on a technology that is virtual (from the Latin “virtus”, strength) in the sense that it doesn’t depict an apparent world but rather creates or defines the world as it is, or becomes.

The Marubo material also problematises technology. In colonial thinking, indigenous peoples were considered to lack technology, making them backward or underdeveloped. At the same time, the notion that myths belong exclusively to so-called “primitive cultures” is called into question, since technology in the West also has mythical overtones, such as the belief in its effectivity and progress.

The Otolith Group

Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar: ”Anathema” (2011)

In ”Anathema”, advanced information technology is shown as an environment where capital is a sentient entity that touches and probes human bodies. The film is based on television commercials for LCD systems – touchscreen technologies – that Eshun and Sagar have found on the Internet. The found material has been manipulated using software that allows them to break up the surface of the filmed image. The duration of ”Anathema” hence consists in a “journey” from the level of the representational image down to the level of colours and pixels that compose the image. Here, in the image’s digital DNA we encounter dreamy abstract landscapes. ”Anathema” seems to say that although capital pulls us into its dreams, we can perhaps resist its seduction: other desires and spaces in time can thus arise – even within the commercial flows of images and technologies.

Branko Petrović and Nikola Bojić

”Socio-medial evolution” (1970)

Compiled and presented by Nikola Bojic

In 1972, diplomats from 133 countries met in Stockholm for the first United Nations conference on the environment. The result planted a seed for future international bodies, political programmes and environmental declarations, such as the Paris Agreement of 2015.

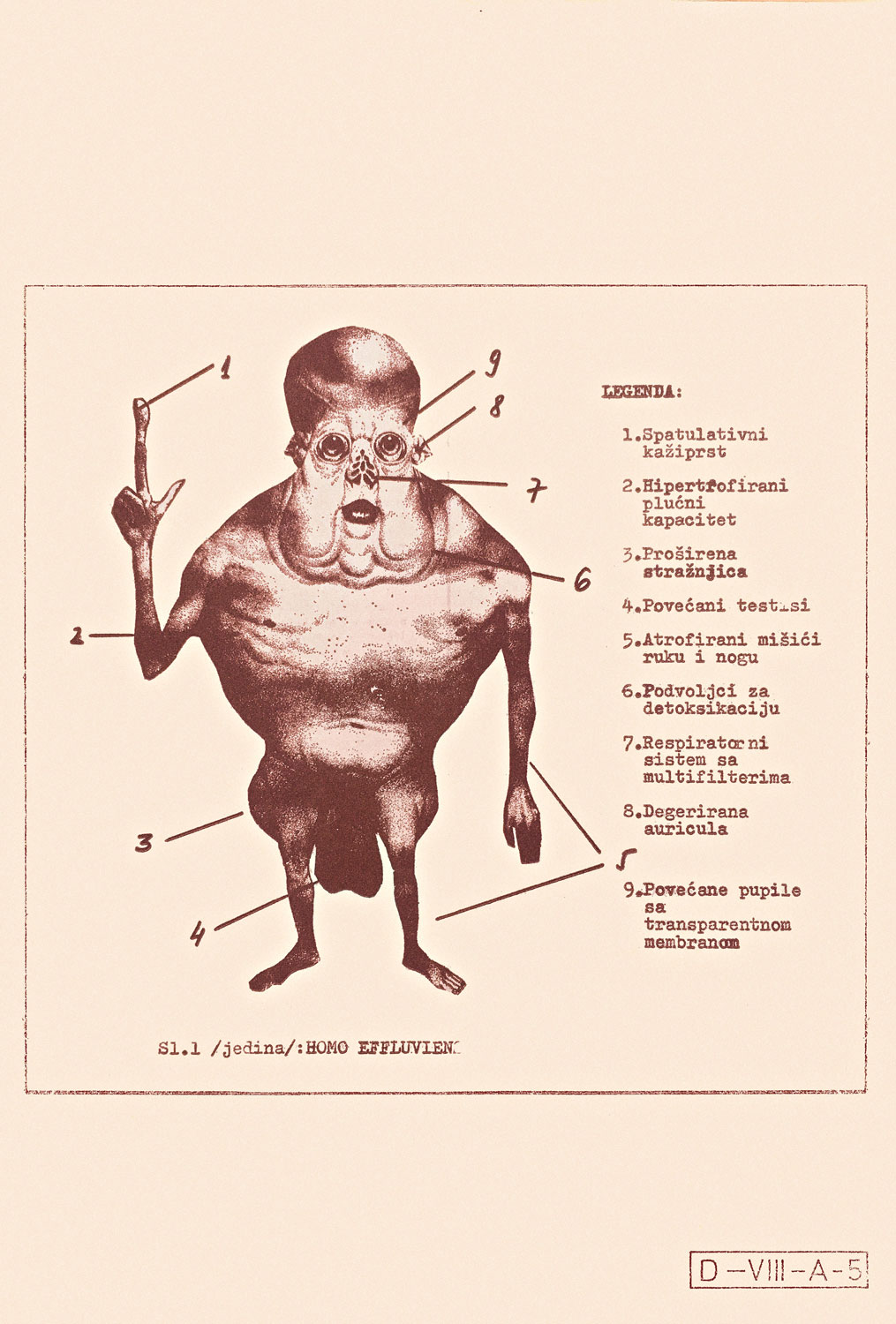

Branko Petrović (1922–1975), a Croatian architect and city planner employed by the state, had conducted a study in 1970 consisting of thirty-six diagrams of human, technological and ecological systems, as well as the media. Petrović advocated a synthesis of such analyses in order to urbanise postwar landscapes. One of these diagrams shows ”Homo Effluviens”, “effluent man”, in whom changes in the earth’s atmosphere have led to an increased lung capacity. The muscles are atrophied but the index finger is well developed – an adaptation to the main activity of pressing buttons. The Yugoslav government intended to offer Petrović’s drawings as a starting point for discussion in Stockholm, but neither he nor his study made it to the conference in the end. Today the diagrams function as almost fifty-year-old cosmograms or depictions of the world through which we can navigate the Anthropocene, “the human epoch”.

Primer

With Emil Rønn Andersen, Eva Löfdahl, Amitai Romm, Aquaporin and Novo Nordisk

A contemporary version of the 1960s-era collaboration between art and business, Primer is a platform for artistic and organizational development. In an unusual arrangement, the group is hosted by the biotech company Aquaporin, that develops water purification products. From there they organize exhibitions and public programmes.

For the project that Primer developed for ”Mud Muses” they are exhibiting Aquaporin’s first industrial prototype, used to manufacture biomimetic membranes. Now defunct, the large industrial machine resembles a shed skin, and has been repurposed as a host body for various artefacts, among them works from Moderna Museet’s collection selected by the group. By juxtaposing art and other objects with a machine that represents an innovation within synthetic biology, Primer seeks to evoke associations and propose a new relationship between biology, digital technology and artistic thinking.

Robert Rauschenberg

”Mud Muse” (1968–1971)

Between 1967 and 1971, the Art and Technology Program at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art paired artists with private corporations to produce new artworks. When Robert Rauschenberg (1925– 2008) was making ”Mud Muse” he chose to work with engineers from Teledyne, Inc. In the work, sounds in the form of compressed air pass through valves to make little geysers erupt in a minimalist vat containing thousands of pounds of synthetic mud made from glycerine and finely ground volcanic ash. A system plays various high-frequency sounds through the mud, setting off new sounds that the work plays back to itself to become part of the work’s recursive action.

The artist made no bones about the work’s lack of morality and content, stating dryly that it had “no lesson” and no “interesting idea”. He explained that ”Mud Muse” instead operated on “a basic, sensual level”, thus making it an open question whether we are looking at a “primal soup” or an apocalyptic wasteland.

Anna Sjödahl

”The Central Computer in Sundsvall” (1978)

In 1977, the Swedish National Institute for Working Life initiated a three-year research project whose aim was to investigate the effects of the increased presence of computers and automation in the workplace. The artist Anna Sjödahl was invited to execute a series of drawings and paintings in workplaces where the arrival of computers had significantly changed the means of production.

Her painting is dominated by a row of austere, dark boxes standing in a room that is as cold and anonymous as the industrial landscape that can be glimpsed outside the window. Traces of human life are eerily absent. The knowledge that the depicted computers, of the make Honeywell Bull 6000, were housed at the Swedish Social Insurance Agency and that they stored the hospital records of Swedish citizens and other confidential information emphasises the relationship between the digital and the physical world. The work reflects the era’s unease about the invisible centralisation and handling of sensitive information, misgivings that are just as palpable today. The painting has been part of the museum collection since 2001, but this is the first time it is being exhibited.

Soda_Jerk with VNS Matrix

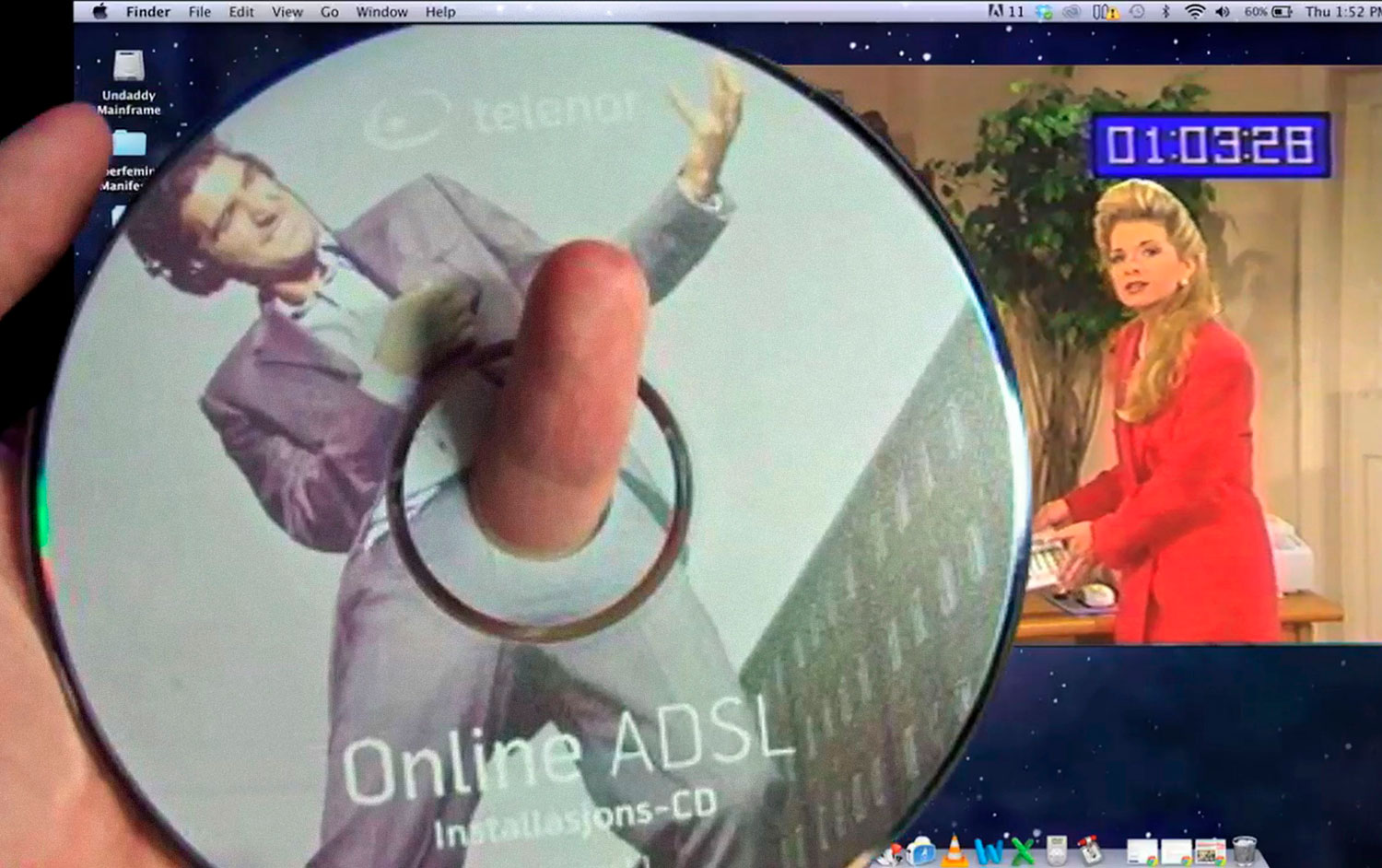

”Undaddy Mainframe” (1991/2014)

It has been said that the term cyberfeminism was first used in the billboard work ”A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century” (1991) by the Adelaide-based artist group VNS Matrix. In it we find a feminist critique of the gendering of technology: technology is purported to be neutral but Western culture has typically coded it as being a carrier of male reason. As before in the history of social and progressive movements, the manifesto is an inflammatory text that calls political self-empowerment into being. In the cyberfeminism of the 1990s, this “subjectivisation” is also marked by an expansion into new and unknown terrain; not only a “We demand” but also a “Who can we become now?”

VNS Matrix’s work was updated in 2014 by the Melbourne-based duo Soda_Jerk, that has added two video works to the billboard’s lesbian unicorns. In homage to VNS Matrix, Soda_Jerk’s installation extends the cyberfeminist view of technology as gendered.

Jenna Sutela

”I Magma” (2019)

The work ”I Magma”, which was specially produced for the exhibition, consists of nine handblown, headshaped lava lamps, which bear a certain resemblance to the artist herself. Lava lamps were popular in the 1960s, the hippie era with its fondness for psychedelic technology and drug-induced experiences. In the lamps, which are heated from below, a kind of coloured magma flows up and down. Jenna Sutela’s self-portraits in lava are connected via direct video feed to a machine learning programme that looks for signs in the movement of the lava via codes from the ”I Ching”, the ancient Chinese “Book of Changes”. Thus, using the feed from the coloured sludge in the “heads”, the computer generates predictions based on the shapes that occur.

Jenna Sutela’s work brings together the scientific and the esoteric, technology and mysticism, and, more recently, she has been exploring the ghosts in the intelligent machines we create. She has stated that ”I Magma” is about getting in contact with the non-human conditions of our computers as interlocutors and infrastructure, as well as how computers escape their human origins by connecting to each other.

Suzanne Treister

”The Rosalind Brodsky series” (1995–1997), ”Hexen 2.0” (2009–2011) etc.

Suzanne Treister’s paintings from the 1980s are of fictitious computer games, and in the early 1990s she produced her first computer piece by hacking games on an Amiga computer. In the mid-1990s she started working with the fascinating time-traveller Rosalind Brodsky, an avatar employed by a military research institute in the future. In a CD-ROM game, Brodsky travels with the help of specially designed costumes to key moments in history, such as the Russian Revolution or the Swinging Sixties in London. On one occasion, the avatar manages to redirect history in order to save its relatives from the Holocaust.

In ”Hexen 2.0” the focus is rather on possible futures, since the work recounts the history of cybernetics via tarot cards. Treister explores and changes our beliefs about technology, using for example watercolours or the ritualised information architecture in tarot decks and the cosmogram. Apart from being an early cyber feminist, Suzanne Treister is a pioneer when it comes to digital and media-based art, who has gone from intoxicated curiosity to a sceptical and critical attitude to new media and issues such as who controls the Internet, software and all forms of data.

Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas

”The Mushroom Power Plant” (2018–2019)

The Urbonas undertake artistic research that is both applied and speculative. In ”Mud Muses” they present an in-process view of their work towards developing a functional prototype of a battery that generates electricity from mushroom and mud bacteria. The installation focuses on processes of carbonisation that are central to making such a biotechnology functional. Components that normally are hidden inside the black box of the battery become visible. Instructions, diagrams and images representing details of this “mushroom power plant” have been printed and engraved on various materials that have been used to make it: silicone rubber, technical felt, copper and aluminium plates, as well as Plexiglas.

The Urbonas have backgrounds in the “mycophile” – fungi-loving – culture of Eastern Europe. With reference to authors such as J. G. Ballard and the Strugatsky brothers, the artists’ fungi-tech conjures a kind of science-fiction approach through which technology becomes something fundamentally different from human triumph over nature.

Vision Exchange Workshop with Akbar Padamsee and Nalini Malani

Nalini Malani: ”Taboo” (1973), ”Utopia” (1969–1976) etc.

Akbar Padamsee: ”Syzygy” (1969–1972)

Mumbai’s Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW) (1969–1974) was initiated by the painter Akbar Padamsee as an open studio for conversations and art production. In the mission statement he claimed that with the advent of electronic technology and cybernetics, a new challenge faced the artist that required a new idiom. Based on a mathematical pattern, Padamsee’s animation ”Syzygy” (1969–72) thus develops a “theory of the programming of forms”.

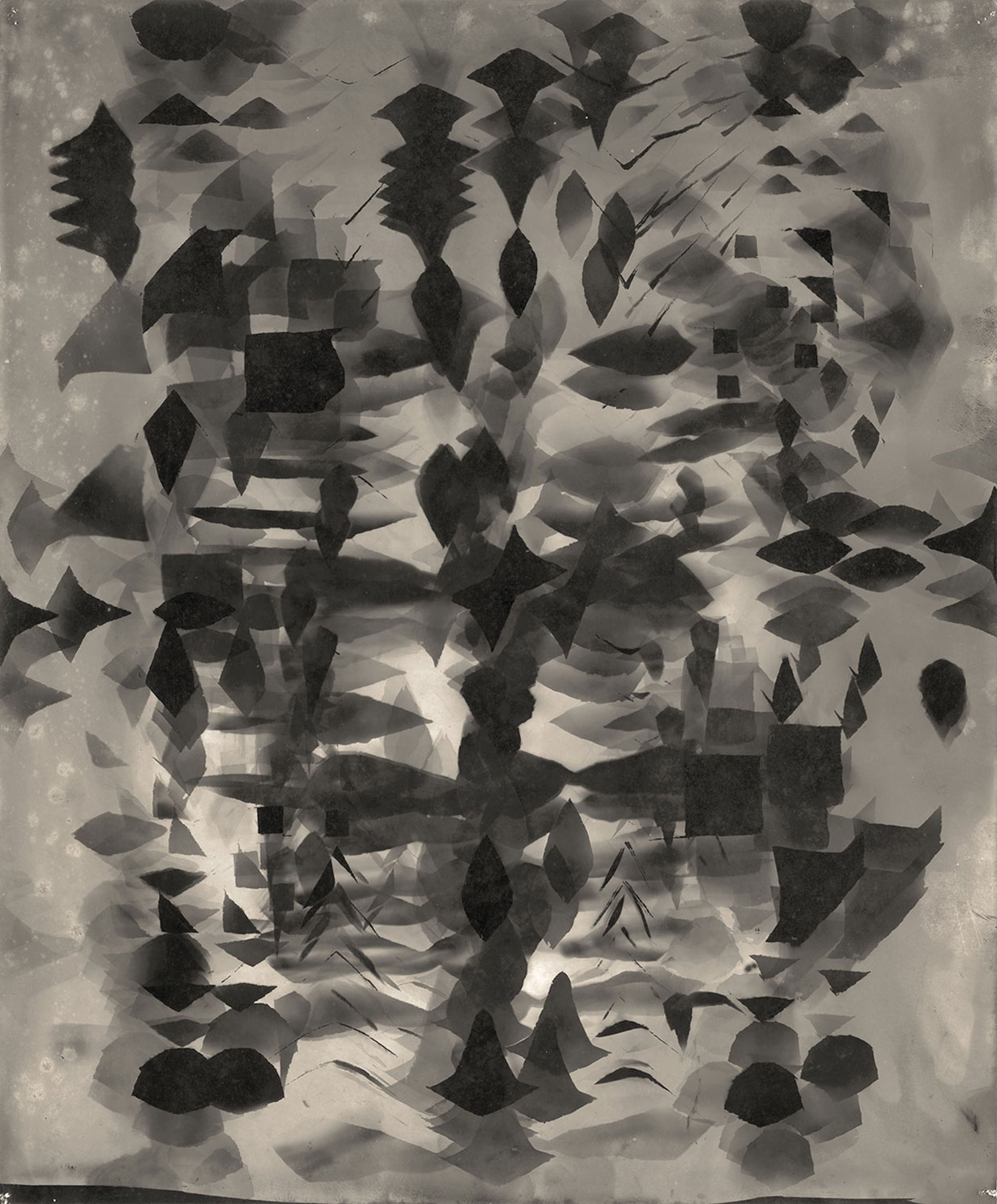

In her films and camera-less photographs from VIEW, Nalini Malani explores social transformation in post-colonial India. Her double projection ”Utopia” (1976) juxtaposes a montage of abstract, colourful architectural reverie with dystopian, black-and-white vistas of new cityscapes. ”Taboo” shows that access to the production apparatus was gendered in the weaving societies that forbade women from touching the loom since they were considered impure. In Malani’s photograms from the period, organic and synthetic structures and textures appear in a shadow-play of nature and culture.