Carolee Schneemann, Eye Body # 20, 1963 Acquired with funds from the Second Museum of our Wishes, Moderna Museet. © Carolee Schneemann/ Bildupphovsrätt 2016

Works in the exhibition

Ignasi Aballí (1958)

Ignasi Aballí’s work Persones consists of a long line of dirty footprints along a wall. They were made by the artist leaning against the wall and resting one foot languidly against it. The work also serves as a kind of choreography, since the audience is invited to complete it by leaning against the wall and leaving dirty footprints on the normally spotless, white museum wall. Aballí is consumed by the issues of absence and disappearance, and various ways of capturing time. His practice is often conceptual, based on his background as a painter.

William Anastasi (1933)

Back in the early 1970s, William Anastasi began working on a series of blind drawings when he was on New York subway. Often, he was on his way to John Cage to play chess. With his sketchpad in his lap and a pen in each hand, he would put on his big earphones and close his eyes to concentrate and achieve a meditative state of mind. His body moved with the lurches, stops and accelerations of the train. Like a seismograph, Anastasi registered the changes in his position. By making himself into an instrument for registering the movement of the train, he renounced his authorship of the drawings. The title of the work is the time when it was made.

Janine Antoni (1964)

Janine Antoni uses her hair as a paint brush to paint the gallery floor with Loving Care hair colorant. Antoni explores the daily rituals we perform on our bodies. She takes everyday activities, such as eating, bathing and mopping the floor, and transforms them into sculptural processes, imitating the rituals of art. She carves her teeth and paints with her hair and eyelashes. The materials she uses are ones that are normally used on the body to define it in society – soap, lard, chocolate and hair dye. Their particular significance to women means that her works are interpreted differently depending on the gender of the viewer, she claims.

John Baldessari (1931)

Being the son of a landlord, John Baldessari occasionally had to redecorate flats. He used to pretend he was making a painting when he painted a wall. This enjoyable conceptual exercise helped him get through the monotonous chore. He also began thinking about the difference between one kind of painter and the other. In Six Colourful Inside Jobs, Baldessari lets a person repaint a room for six days in the six primary and secondary colours, filming it all from above. Hours of painting becomes minutes of film. The title is a pun. Inside Job alludes to a Hollywood detective drama. The time corresponds to six working weekdays. Like God, the painter gets to rest on the seventh day.

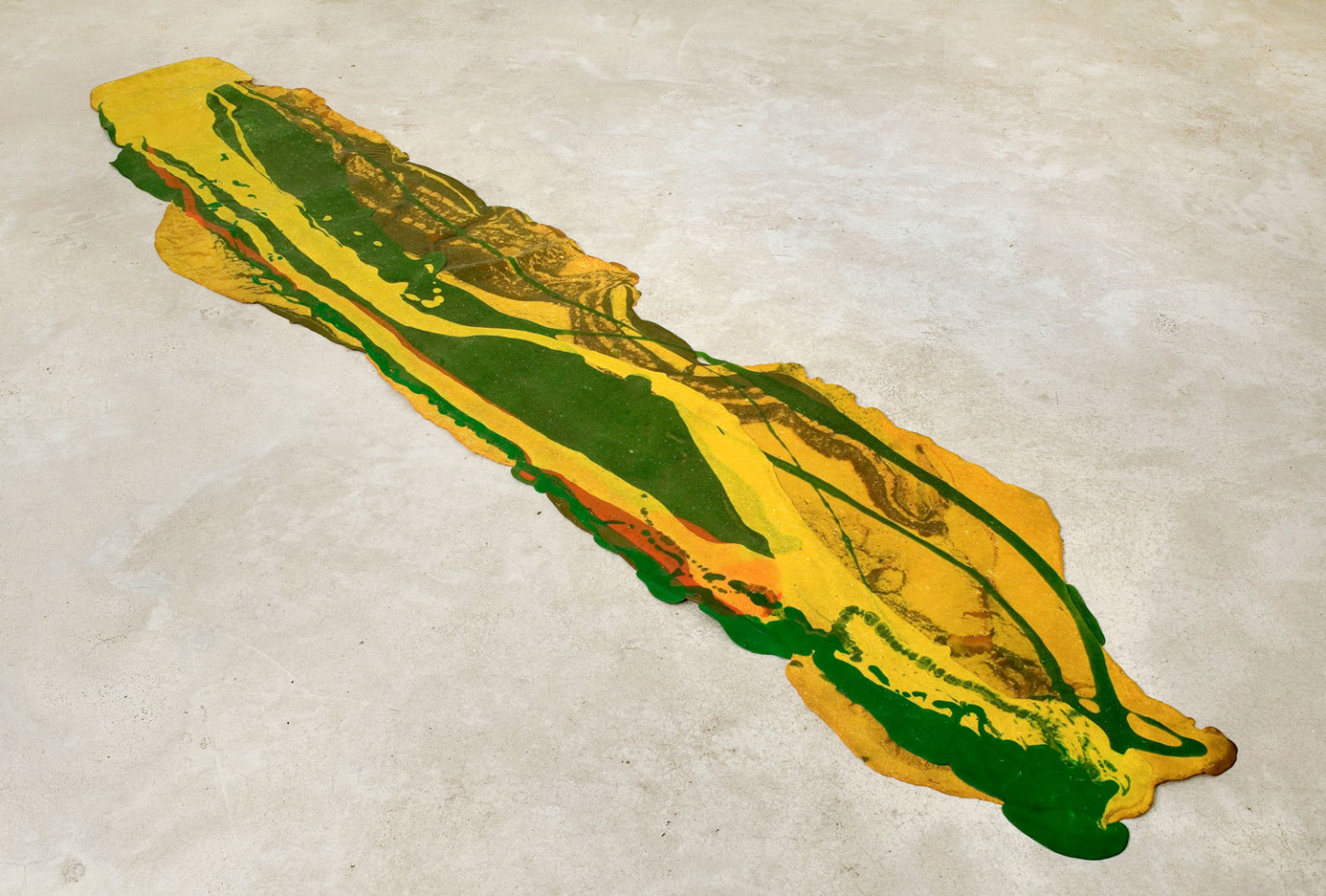

Lynda Benglis (1941)

In Lynda Benglis’ series of works, Pours, paint is poured from large vats and left to dry on the floor. Thus, the paint has the character of a sculpture, dried paint with no “support” in the form of a canvas or panel. Unlike Pollock, the painting is not hung on a wall but is installed directly on the floor. In addition to their painterly and sculptural qualities, Benglis’ works are also a commentary on Pollock, which is further enhanced in the pictures published in the American magazine Life in 1970, together with a smaller picture of Pollock painting.

Bildupphovsrätt 2017

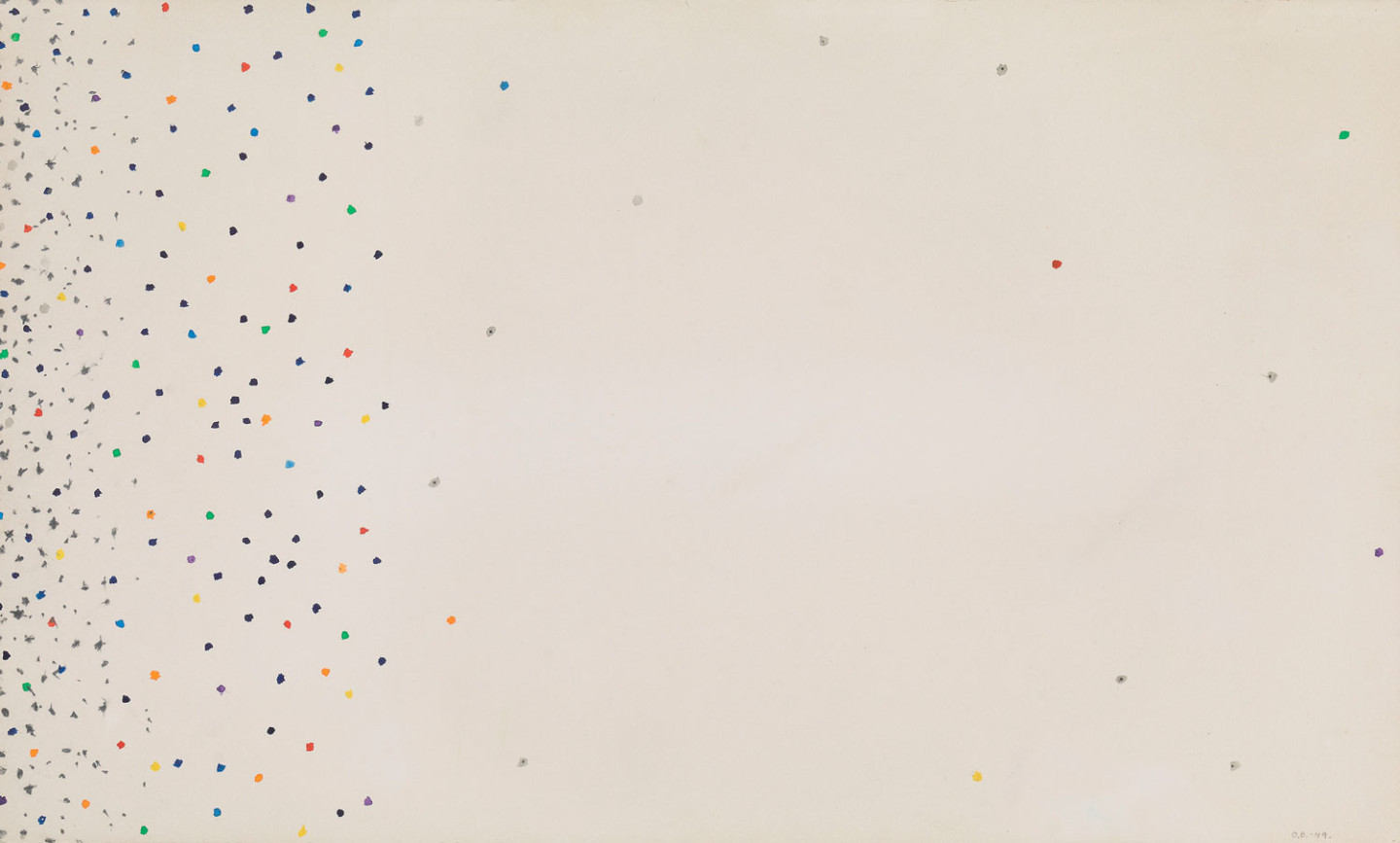

Olle Bonniér (1925)

Olle Bonniér first showed his work at a legendary group exhibition in Stockholm in 1947. Two years later, in 1949, he created the work Plingeling, which is both an abstract painting and a music score. This white painting could be seen as an iridescent universe. The dots arising in this universe have irrational orbits, occasionally colliding with each other so that a tinkling sound arises. Plingeling does not contain any explicit instructions for how it is supposed to be played, and the result is different every time it is performed. Bonniér’s work is an early example of performative painting, a work created as a painting but incorporates instructions that can be transformed into music.

George Brecht (1926–2008)

Water Yam is an artist’s book that Georg Brecht published originally in 1963, in a box designed by George Maciunas, who wrote the Fluxus Manifesto. This box, which is sometimes called the Fluxbox or Fluxkit, contains cards of different sizes that are event scores, or Flux scores, for various kinds of happenings. The scores often leave room for chance or coincidences, forcing the user, or the audience if the score is performed publicly, to make their own interpretation and thus become co-creators of the work. Brecht said that his scores were meant to ensure “that the details of everyday life, the random constellations of objects that surround us, stop going unnoticed”.

Tony Conrad (1940)

When Tony Conrad arrived in New York in the 1960s, he was sceptical of the art scene but discovered the vibrant film scene, finding it more interesting since it was independent of the art institutions. Conrad wanted to combine film with the exciting new developments in painting. One of his strategies was to make ultra-long movies. Andy Warhol had made films that went on for 24 hours. Conrad’s work Yellow Movie is a film that has been going on for 40 years! The idea is that the cheap paint gradually changes colour over time. No one can measure the change taking place in the “movie”, but this is of no consequence, since it is taking place in your own imagination, says Conrad.

Öyvind Fahlström (1928–1976)

Öyvind Fahlström was a multifaceted artist who worked experimentally and in several disciplines. He was a visual artist, a writer, a film-maker and a composer. His encounter with pop art and the comic book culture in New York in the early 1960s had a radical impact on his art, and he began making variable paintings in the form of board games. Games were his way of illustrating political, social and economic power constellations. Viewers are intentionally invited to move the markers and elements of the paintings to form new combinations.

Ceal Floyer (1968)

Ceal Floyer’s main preoccupations are light, shadow and colour, and how we perceive and interpret the world with our senses. With a prolific use of modern technology, she creates idea-based works that combine elegance with apparent simplicity. Here, the monitor screen is entirely filled with interchanging colours. These are in fact close-ups of a glass of water, into which brushes with different pigments are dipped. The pigments correspond to the basic colours of video technology. Thus, Floyer brings together analogue and digital colour.

Pinot Gallizio (1902–1964)

In 1959, Pinot Gallizio’s manifeso for industrial painting was published. Industrial art was to be produced mechanically and be made available to everyone. Art was to be made among the people, or not at all. The idea was that thousands of kilometres of canvas would be mass-produced and then distributed to the people, to liberate them from the bourgeois art that had led to financial speculation and contributed to perpetuating the class divide. Quantity and quality would become one and the same thing, thus ending the artwork’s status as a luxury commodity. Gallizio was also a founding member of the radical leftist art movement known as situationism, which wanted to liberate art from its role as a fetishist commodity of capitalism.

Cai Guo-Qiang (1957)

Cai Guo-Qiang uses gunpowder and fireworks to draw pictures in the air. Sometimes these works last for a few seconds, sometimes the explosions leave traces on paper or canvas. Since 1989, Guo-Qiang has been making “projects for extraterrestrials” monumental explosive works directly on the ground, so that they can be seen from other planets. In 1998, Guo-Qiang carried out a project on the frozen waters between Moderna Museet and the Vasa Museum: a trail of fuses and gunpowder made the waters between the two islands part for a moment, like the Red Sea in the Bible, when Moses led the Jews to the promised land.

Sadaharu Horio (1939)

Sadaharu Horio showed his work for the first time with Gutai in 1966. With more than 100 exhibitions and performances annually, he stresses that exhibitions are not a separate situation but an extension of life, and that day-to-day activities are basically a performance. Each moment is different and irreplaceable. Horio devotes himself to the possibilities of the moment with the openness of a child. In a continuous ritual, he covers the everyday objects around him with paint every day. To avoid having to choose colours, he sticks to the order of the paints in the box, and thus evades any personal trace. This painterly ritual could be taken over by anyone and perpetuated eternally.

Yves Klein (1928–1962)

For Yves Klein, the colour blue represents emptiness, sky and sea – the intangible. Nearly all his works are monochromes in his signature colour, International Klein Blue. He used a special binder that does not affect the lustre and intense character of the pigment. Klein’s anthropometries are paintings made with an audience, like performances. The models painted directly on each other’s bodies and pressed themselves against the canvas, or dragged each other across it, like living brushes. Klein is said to have got the idea of painting as a direct imprint of the body on seeing a stone in Hiroshima with the shadow of a human being burned into it by the atom bomb. This sight may also have inspired his fire paintings.

Akira Kanayama

Akira Kanayama was the secretary of the Gutai group. He jokingly said that the position involved so much work that he had no time to paint and instead let a remote-controlled toy car paint for him. The resulting Work (1957) can be seen as a critique against Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, with which they have some resemblance. In Kanayama, the male genius who expresses his feelings with paint is supplanted by a toy car that randomly zooms around the paper, leaving a trail of paint, or, as in the work Footprints, where the artist’s soles have left tracks on the paper. Kanayama thus challenged the artist’s personal relevance to the quality and ingenuity of the work.

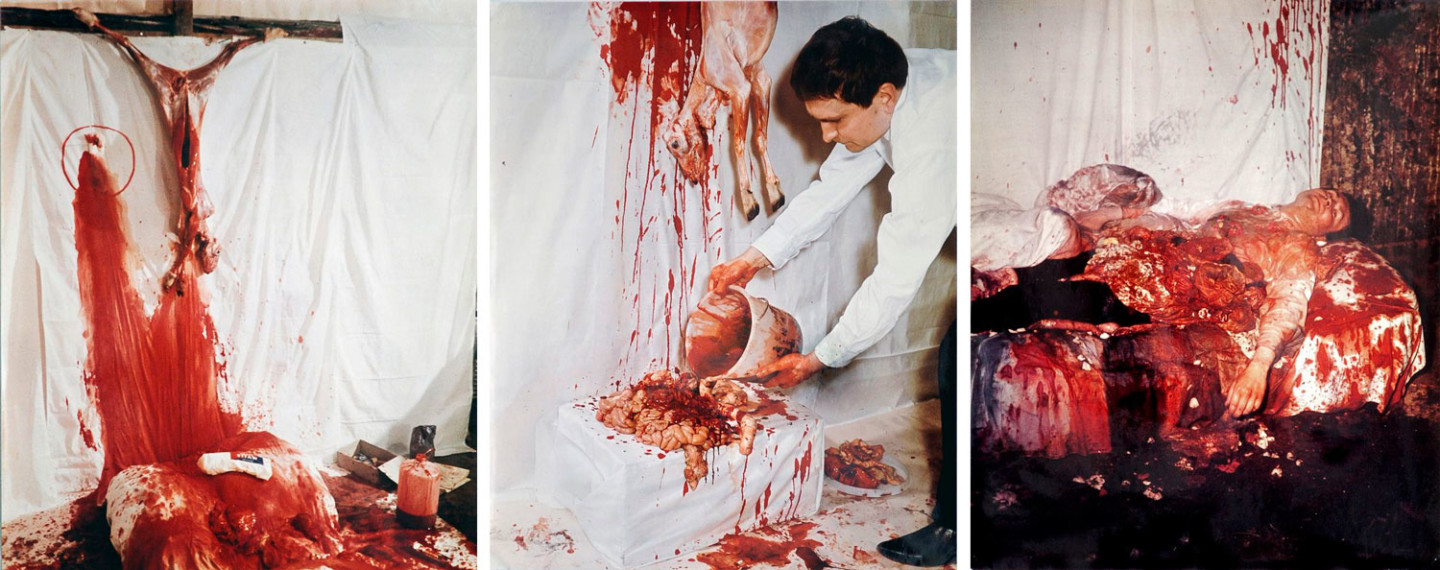

Paul McCarthy

The Black and White Tapes are a compilation of 13 early performances from the 1970s. This selection shows the budding development of themes, the brutal corporeality, and the performance persona that has come to signify his oeuvre. Like Hermann Nitsch and the Vienna actionists, Paul McCarthy explores loss of control, but without the ritual elements and with direct links to Hollywood superficiality and material abundance. Common to both Nitsch and McCarthy is that the liquid form (paint) is not directly limited to a canvas but spills in such a way as to resemble body fluids that suddenly and catastrophically appear all over the place.

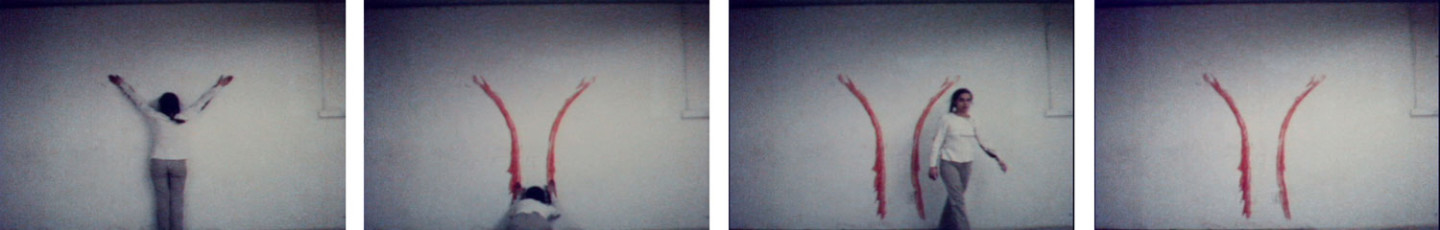

Ana Mendieta

In the early 1970s, Ana Mendieta began creating silhouettes and “earth-body sculptures” out of mainly blood, earth, fire and water. Using her body as her tool, she made human imprints on nature. Her performances were documented on film. Ana Mendieta was the first to combine the two contemporary movements of land-art and body-art, resulting in works involving the themes of life, death, place and belonging. Mendieta’s ritualistic use of blood, gunpowder, earth and fire is also linked to the Cuban religion of Santería. As a thirteen-year-old, Mendieta was sent from Cuba to the USA, where she was raised in orphanages. Her search for identity and a sense of belonging imbues Mendieta’s entire oeuvre.

Saburo Murakami

Saburo Murakami was a co-founder of the Gutai group and one of its most seminal members. He formulated the group’s concept of outdoor exhibitions and created performance acts in which he challenged painting by moving its boundaries and exploring whether the genre could go beyond paint on canvas. The work Six Holes is a literal and theoretical blow against painting. The artist has made holes through multiple layers of brown paper stretched on a frame, using various parts of his body. The result of his experiments was new kinds of “paintings”, a first artistic attempt to renegotiate the relationship between performance and object.

Courtesy Linda Pace Foundation, San Antonio

Rivane Neuenschwander

Rivane Neuenschwander calls her art “ethereal materialism”. She uses everyday materials to express the passing of time, the fragility of life and human relationships, often allowing chance and interpretative processes to determine the final result, as when she asked two chefs to create a meal based on a shopping list she found on the floor of a supermarket. In the work Secondary Stories (2006), brightly-coloured circles of tissue paper are wafted above an inner ceiling with fans. Now and then, they randomly fall to the floor, forming new patterns like drops of paint.

Hermann Nitsch

The Vienna Actionists’ theatrical and aggressive painting performances and body art combined art with rituals and religion. In many respects, Hermann Nitsch’s works are like classical dramas, with their striving for catharsis, a form of healing purification through suffering. They offer resistance to the fact that modern Western man is so far removed from the rituals that caused ecstasy with its cleansing and regenerative effect. According to these ideas, we cannot experience great joy unless we can also experience pain, grief and fear. The practices of the Vienna Actionists can be seen as part of the Austrian expressionist tradition, with elements of Catholicism, psychoanalysis and rebellion against the bourgeois, hierarchical social order.

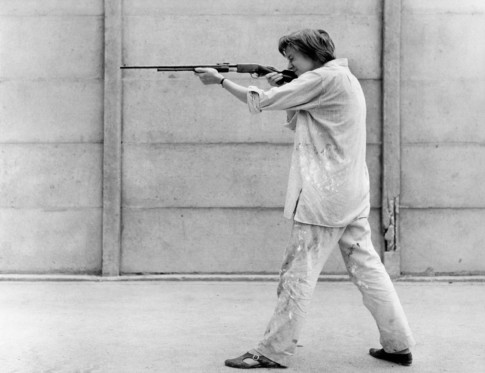

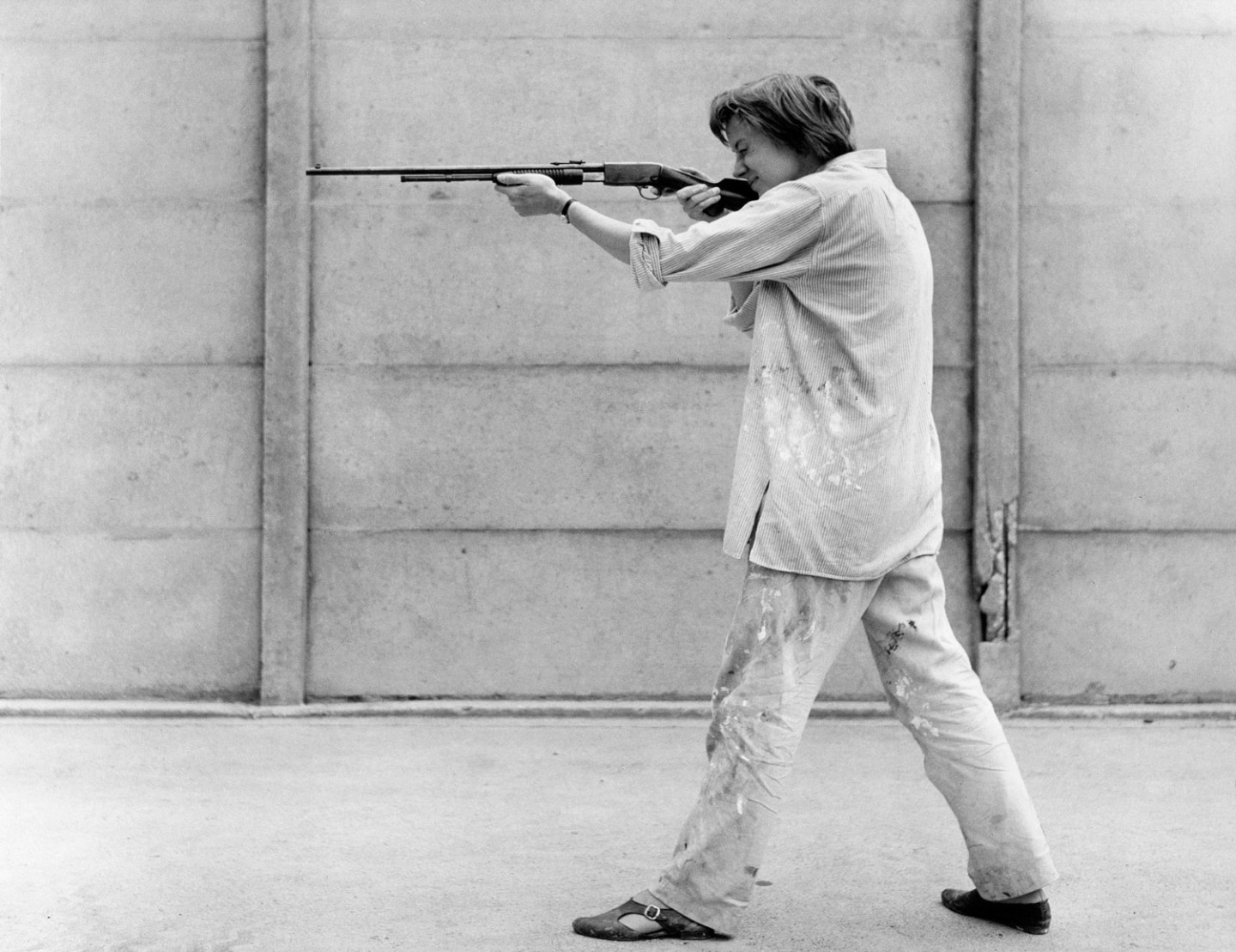

Niki de Saint Phalle

In the early 1960s, Niki de Saint Phalle shook the male-dominated art scene to its foundations with her Shooting Pictures (Tirs). In these works, she covered paint containers with thick layers of plaster on a wooden board. She then fired a rifle at them from a long distance; when the bullet hit the containers, the paint ran out randomly on the plaster. The act of shooting became an exceedingly intentional act that could also be seen as a performance. Describing the act, Niki de Saint Phalle said she was shooting at all men, her brother, society, the Church and school.

Jackson Pollock

When Jackson Pollock had his breakthrough in 1947, he had converted to an entirely new and revolutionary way of painting. Placing large canvases directly on the floor, he dipped brushes and sticks into pots of liquid paint and let it drip onto the canvas as he moved around all four sides of it, while listening to loud bebop or other jazz music. This method, he said, was related to Native American Indian ritual sand paintings made with coloured sands that were strewn in beautiful patterns. For Pollock the act of painting itself was as important as the finished work. His way of painting was called Action Painting, and he is regarded as one of the seminal abstract expressionist.

Niki de Saint Phalle / Bildupphovsrätt 2017

Robert Rauschenberg, Niki de Saint Phalle

In May 1961, the exhibition Movement in Art opened with a party. Niki de Saint Phalle had attached a myriad of paint-filled bags to a theatre backdrop, on top of which she placed a plastic sheet and a carpet, to form a dance floor. When the guests began to dance, the bags burst, creating an abstract painting. After the party, Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver (founder of Experiments in Art and Technology, E.A.T.) were the only remaining guests. The painting was still lying on the stage. They took it outside, and Rauschenberg suggested that they could improve the work, and perhaps attract the attention of a cab driver, by spreading it across the road. Several passing cars left tyre tracks on the canvas before a cab finally stopped.

Carolee Schneemann

Carolee Schneemann is a pioneer of performance and feminist art. In the early 1960s, she used her body as artistic material and was the first American artist who worked with “body art”. In Eye Body she appears nude, smeared in paint, grease and chalk. Transferring painting from the canvas to her body, Schneeman challenges the contemporary female role and the prevailing attitude in art to the female body as an object to be depicted and looked at. She has been criticised for being drastic, but her spectacular works always have a purpose. As both the subject and object of her paintings, she reclaims the power over the female body and sexuality. In addition to performances, Schneemann makes assemblages, films, videos and installations.