Sharon Hayes, In My Little Corner of the World, Anyone Would Love You, 2016 5-channel video installation. Performer: Swift Shuker. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin © Sharon Hayes

In My Little Corner of the World, Anyone Would Love You

Text: Sharon Hayes

For many years, I have been positioned as an artist who engages public space. In response to this characterisation, I often clarify that my interest in the street came from an interest not in public space but in public speech. In this way, I’ve been drawn to various theorisations of publics. The two constructs that have been most foundational to me are that of Hannah Arendt, as elaborated in her work ”The Human Condition” (1958), and Michael Warner, as articulated in his book ”Publics and Counterpublics” (2002).

While Warner and Arendt’s descriptions of the conditions of a public remain vital for me as an artist, my conversations over the last five years, particularly with students, have suggested these constructions of public are increasingly inadequate in describing the conditions of public appearance today.

In the wake of this shift away from a paradigmatic formulation of a public, I’ve found myself thinking more about publicity and its complicated operation vis-a-vis queer living.

The word publicity derives, etymologically, from the French words publique and publicité. In its early usage, publicity was employed to describe the condition of being public or the act of making something known, of exposing something to a public. Only in the early twentieth century did the meaning of the word shift into one describing the business of promotion.

In this moment, it seems the demands on an artist – or an activist, or even on a citizen – to be his/her/their own publicist have grown exponentially. There are endless free, easy-to-use, and incredibly powerful computer applications that facilitate the dissemination of a wide range of materials to high volumes of people. Not only has there been an incredible advance in the technological capabilities of various organisational, administrative, and communicative systems and platforms, but the speed with which these platforms are bought and replaced has also accelerated immensely. With each paradigmatic technical change, new publics emerge. The integration of these forms of publicity into the practice of art intersects with artists beginning to embrace social media platforms as a site for the distribution and even the production of art.

It has been said that there is no such thing as bad publicity. While the current political moment proves this adage to be almost irrefutable, the distraction of judgment – of deciding what’s good and what’s bad publicity – and the perception of overload occlude the deeper consequences of the word publicity itself. They willfully distract critical responses.

In their 2016 book ”Queer Cinema in the World”, Karl Schoonover and Rosalind Galt suggest, “Wrapped up in the Western optic of coming out is a fraught catch-22 in which queer people are either too closeted or overly blatant”.(1) They posit that putting the queer body into cinema functions as a hyperbolic “going public”. Indeed, while we often retroactively reverse cause and effect, the early policing of gender – manifest in US cities in laws, imposed after World War II, that required citizens to wear at least three articles of clothing conventionally associated with the gender they were assigned at birth – arose in response to what was perceived as the increased presence of gender-non-conforming bodies in public space.

The publicness of the queer body is more noticeable for queers of color. Scholar Anthony Reed, speaking to sociologist Elijah Anderson’s work on “cosmopolitan canopies”, asserts that “bodies are mutually visible, but some bodies, especially those that are racially marked, retain a surplus visibility”.(2) In his analysis of what he calls “religious words” in the work of James Baldwin, scholar Michael Cobb asserts, “the logics of pain in political subject formation are also the logics of normal publicity – being public is described as an experience of injury”.(3)

The notion of publicity, something appearing in public and therefore being shared by any number of people for whom it appears, is, of course, determined by multiple conditions. At any given time and place, certain things are intelligible, visible, and audible and other things are not. That certain things might be intelligible, visible, and audible to some people and not to others suggests, in a more foundational manner than the purely anecdotal, that how, why, whether, and for whom things are made public is at the same time a political, an economic, and an aesthetic concern.

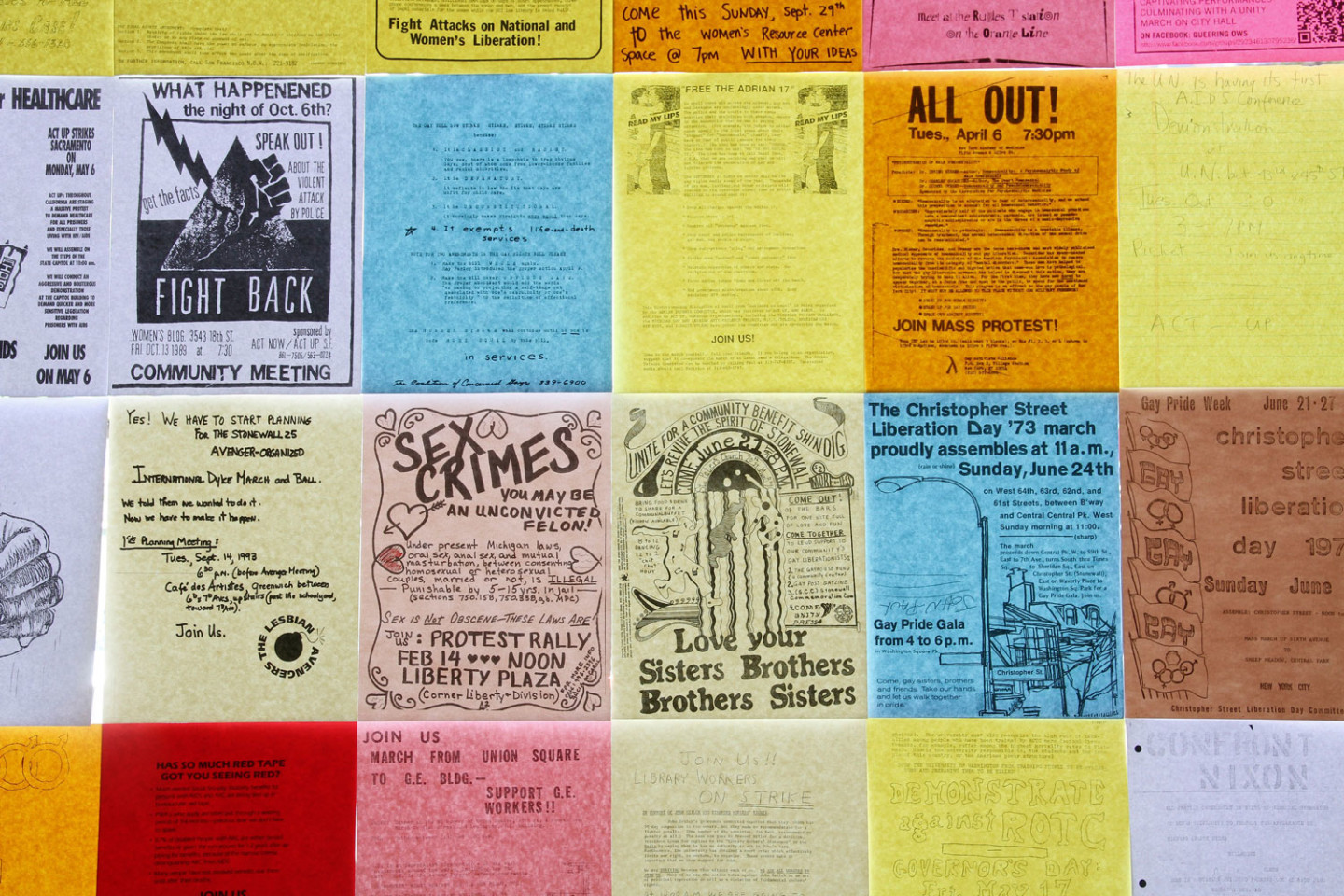

”In My Little Corner of the World, Anyone Would Love You” is a five-channel video installation in which thirteen readers speak excerpts from a heterogeneous field of feminist, lesbian, lesbian-feminist, gay-liberation, and trans newsletters and small-run magazines published in the US and the UK between 1955 and 1977. Filmed in five rooms of a single domestic space, the readers also perform small activities that suggest narrative but don’t add up to a story. Five projections are installed on a single, long, public posting board that bisects the exhibition space.

I embarked on this installation because Studio Voltaire commissioned me to make a new work as part of How to Work Together, an exhibition series organised by three London institutions.(4) The invitation for me to show work outside of the US is always both compelling and confusing because my work is grounded in US-based histories, in singular relationships, or in the intersections between history and language. To go into another context and ethically approach a moment in history, or a historical text, is therefore challenging. In the case of the UK, of course, there was a small opening that doesn’t always exist because while I was a stranger to the culture and history and an outsider to the contemporary social and political context, I was not a stranger to the language. To draw myself into the project, I began in the Hall-Carpenter Archive, the largest collection of LGBTQ material in the UK.

What is interesting about archival research, particularly when you are a stranger to the materials’ context and histories, is that your lack of familiarity affords you the space to wander in a non-hierarchical way, to wander outside of teleologies inscribed or built in to collective memory.

Wandering around in the archives, I found my way to a group called the Minorities Research Group, or MRG, founded in London in 1963 and informed by the Daughters of Bilitis, an early lesbian organisation created in San Francisco in 1955. I didn’t know of MRG before this encounter. Its primary activity was publishing a small-run magazine called ”Arena Three”; the Daughters of Bilitis’s primary labor was producing and distributing a small-run magazine called ”The Ladder”. These groups published the first continuously running publications by and for lesbians. They were in conversation with each other; they sometimes showed up in each other’s magazines.

I had never been particularly interested in this early moment of LGBTQ activism, the postwar, pre-Stonewall efforts sometimes known as the homophile movement. When I came out as a lesbian and an artist in the early 1990s, that historical period was generally regarded as normative and assimilationist, as if the activists weren’t ready to be radical. I recognize now that my assumption was profoundly naïve and reductive. When I looked, in more depth, at these magazines and newsletters, I was awe-struck by the incredible labor and radical work that went into wrenching the narrative of LGBTQ lives out of the regime of psychiatry and beginning one’s own narratives.

This work did not emerge in a vacuum. There were incredibly important and vibrant magazines and newspapers being published by the Black Left that also forged a critical intellectual space outside of mainstream magazines – including the pan-Africanist newspaper ”Freedom”, for which the writer Lorraine Hansberry reported. Hansberry wrote two published letters to the editor of The Ladder to praise the magazine and to elaborate the importance of examining the social and political conditions and constraints facing women and, by inference, facing women who love women.

The excerpts I use in the piece ”In My Little Corner of the World, Anyone Would Love You” are drawn from two spheres of correspondence: letters from the editors to their readers and letters from the readers to the editors. This is also to say letters from readers to readers, because writers often address other readers by writing to an editor. In those two magazines in particular, people were speaking to each other literally for the first time: a particular individual was speaking to a group of individuals for the first time, but also lesbians were speaking to other lesbians for the first time.

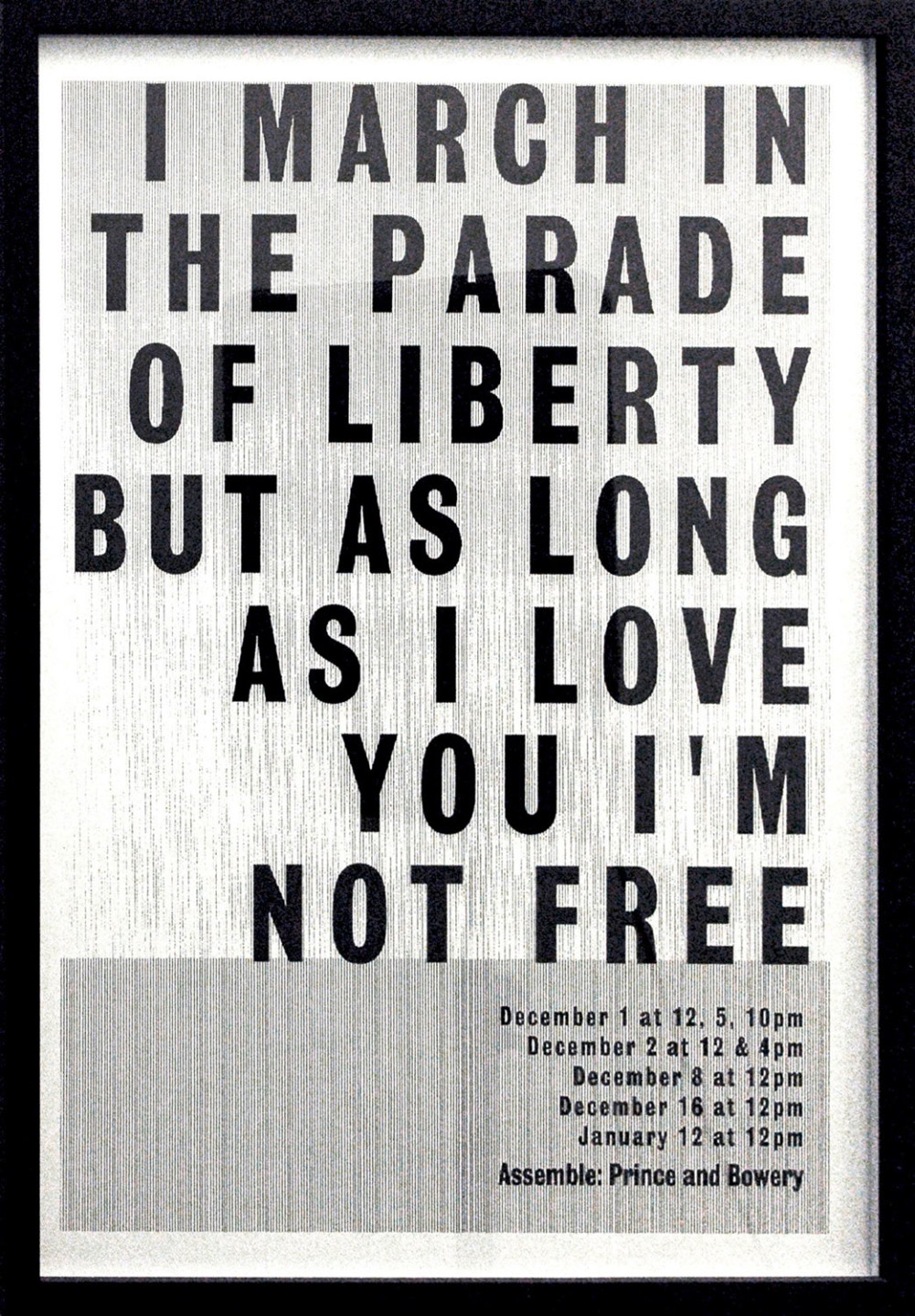

I became interested in the way in which the letters were possible because of something I began to call protected publicity. It’s a very specific form of publicness: any given reader-writer assumed their speech to other readers was intensely protected, and purposefully so, because people were vulnerable should their identities be known. The editors went through a laborious process to keep people unrecognisable, often using no more than initials, or a first name and location. But I also mean protected publicity in the sense that people were speaking to a set of presumed collaborators, people who had an affinity with them and a shared investment in the kind of questions, concerns, emotions, and desires that that writer was trying to articulate.

To repeat an earlier description: the word publicity derives, etymologically, from the French words publique and publicité. In its early usage it was employed to describe the condition of being public or the act of making something known, of bringing something to an exposure with a public. In the case of these newsletters, it is their publicity, the fact that these very private words were addressed to a public forum, that links me as a reader to the original subscribers to the magazines and newsletters. That we can cohabitate as readers (or listeners) across a seemingly immeasurable historical gap is a complex and fascinating condition of language and archival preservation.

In my encounter with these materials in the archives, I was struck by how richly they speak to the present moment, by how much they have to offer us. The communications are deeply emotional and demonstrate the joy and euphoria people felt in finding each other, but also the deep disappointments and conflicts that arise hand-in-hand with that euphoria. Conflicts abound in these documents: over gender expression, over so-called proper behavior in public space, over how to combat police regulation of public space; about the magazine’s content, about the lack of proofreading, about the inclusion or exclusion of certain discussions, about terminology and language. In these documents, the racism of the collectives is called out.

Challenges to white privilege, and to the homogenising of new political identities into an imagined white, middle-class, female-born body, are made and made again. These conflicts belie the idea that first there was some whole and unified construct of lesbian or feminist or even woman that was then interrogated and expanded. They speak to the way in which contestation and struggle are constitutive of feminism, of queerness, of politics. And these conflicts, in my mind, have a lot to contribute to our understanding of the continued violent regulation of non-binary gender expression, the continued impact of racism on political activism, and the continued debates inside of queer, trans, lesbian communities around and about gender as a component of intersectional identity.

To select the readers for my work, I put out a casting call. Although I did not need actors, the casting call allowed for me to solicit the participation of strangers, which was important. I put out a call that asked for queer, genderqueer, gender non-conforming, transmen, transwomen, trans people, lesbians, and dykes who were interested in participating in the project. I addressed that specific breadth of identity positions because I was interested in the coherences and incoherences between two very distinct moments in time. As in most of my work, I steered away from any strategy of reenactment because such a treatment, in my mind, actively refuses or disavows incoherence. In his formative essay “New Ethnicities”, the brilliant cultural theorist Stuart Hall writes:

My own view is that events, relations, structures do have conditions of existence and real effects, outside the sphere of the discursive; but that it is only within the discursive, and subject to its specific conditions, limits and modalities, [that] they have or can they be constructed within meaning. Thus, while not wanting to expand the territorial claims of the discursive infinitely, how things are represented and the “machineries” and regimes of representation in a culture do play a constitutive, and not merely a reflexive, after-the-event, role. This gives questions of culture and ideology, and the scenarios of representation – subjectivity, identity, politics – a formative, not merely an expressive, place in the constitution of social and political life. (5)

My interest in re-addressing these historical documents is to examine them as scenarios of representation, conversation, contestation, observation, debate, and ranting that did not, as Hall says, merely express conditions but also formed openings as well as obstacles that are deeply relevant to what we all face today.

To be an artist is to have the privilege of making things public – to make objects, images, performances, texts, and moving images that appear in public. To be an artist is to have the privilege to make public professions about the world and the things in the world. But I am also invested in the attendant responsibility I have to interrogate the ways in which our public professions intersect with evolving social, political, economic, ideological, technological, and aesthetic conditions that enable things in the world to be seen or not seen, heard or not heard, to touch or not touch, to act or not act.

References

1 Karl Schoonover and Rosalind Galt, Queer Cinema in the World, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016, p. 123.

2 Anthony Reed, “The Erotics of Mourning in Recent Experimental Black Poetry”, The Black Scholar: Journal of Black Studies and Research, Spring 2017, vol. 47, no. 1, p. 3. See also Elijah Anderson, The Cosmopolitan Canopy: Race and Civility in Everyday Life, New York, NY: Norton, 2011.

3 Michael L. Cobb, “Pulpitic Publicity: James Baldwin and the Queer Uses of Religious Words”, GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2001, p. 299.

4 In My Little Corner of the World, Anyone Would Love You was also commissioned by The Common Guild, Glasgow

5 Stuart Hall, “New Ethnicities”, Black Film, British Cinema, ICA Documents 7, London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1989.