J.M.W. Turner, Sun Setting over a Lake, ca 1840 © Tate, London 2011

Pioneer artists

Twombly described himself as a ‘romantic symbolist’, linking himself to the great painters of the nineteenth century. Like Turner’s, his works invoke myth and history, and additionally mourn the loss of classical reference within contemporary culture. Monet looked closely at Turner’s work and Twombly was a keen admirer of them both.

The exhibition presents works from the second half of their careers, when the outward battles have been won but the inward battles commence. In their late paintings the three artists engage in the struggle to come to terms with the passage of time, mortality and loss, as well asserting a continuing vitality through sensuality and eroticism. In seven themes Turner, Monet and Twombly are brought together, not in competition, but as a means to explore the ways in which artists share interests, values and preoccupations.

The exhibition is constructed as a dialogue where the three artists converse across centuries, questioning and challenging each other as though each were present in the same room at the same time.

Curator: Jeremy Lewison

Assistant Curator: Jo Widoff

Atmosphere

When Turner died in 1851 he left several unfinished paintings in his studio. In the wake of Impressionism these paintings have been appreciated as highly as the finished works. These incomplete works suggest that before anything else Turner wanted to establish an atmosphere. ‘Atmosphere is my style’, he claimed, and ‘indistinctness is my fault’. In The Thames above Waterloo Bridge (c. 1830–35) Turner shrouds the river in a blanket of pollution, with chimneys belching out smoke.

The London fog resulted from a combination of atmospheric pressure, pollution from industries and an increased use of coal. Monet painted London in the winter specifically to capture the visual effects of the polluted air. ‘The motif is unimportant to me, what I want to reproduce is what stands between the motif and me’, Monet allegedly said. Monet had taken the same approach in Rouen. In Rouen Cathedral, Portal (Morning Effect) (1894), the cathedral emerges out of the dawn, the coalescence of paint marks forming a structure that parallels the revelation of the façade in real time to the painter.

Twombly too was interested in weather effects. In Orpheus (1979), the mist occludes the name of the eponymous hero, or perhaps of his wife, Eurydice, since all that remains are the letters ‘eu’. Like Monet’s and Turner’s, Twombly’s paintings rely on materiality to create an atmosphere and a sense of mystery.

Beauty, Power and Space

In the mid-eighteenth century, artists became interested in the sublime. The philosopher Edmund Burke (1729–1797) defined it as the experience of anything that excites ideas of terror, pain or peril in the mind of a person who is safe in the knowledge that they are in fact not subjected to danger.

Turner’s stormy seascapes highlight the overwhelming force of the sea. Shipwrecks, catastrophic deluges and rough seas were some of his principal subjects in the last twenty years of his life. In the 1880s, Monet chose increasingly isolated and perilous places in which to paint, emphasising the immensity and harshness of nature. Eschewing figures, Monet encourages the viewer to replace him as the perceiving body.

In Twombly’s four mythological panels Hero and Leandro (1981–1984), Leandro is engulfed by the sea as he swims across the channel to visit the beautiful Hero. Tossed around by the waves in the first panel, he is eventually submerged beneath the spume. In the fourth frame, Twombly inscribes the closing line from a sonnet by John Keats (1795–1821). In addition to human tragedy, Twombly’s theme too is the fury and force of nature.

Naught So Sweet as Melancholy

Twombly used boats as a theme in both painting and sculpture to emblematise the passage of time. Drifting silently, his boats recall the myth of Charon on the river Styx, serrying his passengers from the world of the living to that of the dead.

On a number of occasions, Turner painted works in homage or as memorials to fellow painters or patrons. Peace – Burial at Sea (1842) commemorates his friend the painter Sir David Wilkie. Turner depicts a ship with black sails hove before the Rock of Gibraltar. Wilkie’s body is lowered to the sea in a blaze of torchlight. War. The Exile and the Rock Limpet (1842) depicts Napoleon on St Helena, reflecting on his fate and the lives lost in battle. The hot colours of this painting deliberately act as a counterbalance to the cool colours of Peace, to which it was a pendant.

Turner’s late Venetian paintings, executed after his final trip to Venice in 1840, have a mournful air. Monet’s paintings of the same city were begun on a trip with his wife Alice in 1908. Monet could not resist the temptation of measuring himself against his many predecessors – among them Turner – who had depicted Venice in the past. Many of these canvases were finished after the death of Alice in 1911 when he returned to the Venice motifs with a heavy heart, remembering the happy days with Alice.

The Seasons

In Quattro Stagioni (1993–95), Twombly both mourns the passing of time and celebrates life. The predominant colours key the mood of each season. Like many poets and painters before him, Twombly links the progress of the year with the life cycle. Spring is full of vigour, tempered by the recognition that what rises will inevitably fall. The glorious summer is tinged with the knowledge that ‘youth is infinite and yet so brief’. Autumn marks the moment of panic, when winter begins to draw in and mortality rears its head, but still there is sufficient energy for late blooms. Winter is mute; the galleys glide towards entropy, their forms dissolving, veiled in the silvery tones of the brumal mist and sea.

Monet also recorded such changes in his series of Poplars in the 1890s, as well as in his paintings of flowers whose moment of bloom is tied to specific times of the year. Although not allegorical, these paintings are nevertheless imbued with a strong sense of time. Monet’s series were cycles as much as Twombly’s, and he could not but have been aware of their association with the allegorical tradition of the four seasons.

Fire and Water

Although painters and poets traditionally favoured sunrise and sunset as times of the day to create a mood, Monet was more interested in capturing a particular kind of light and energy. In London, Houses of Parliament. Burst of Sunlight in the Fog (1904) the heat from the sun burning through the water seems more important than the Houses of Parliament themselves.

For Turner the sun is both a life giving and life taking force. Fading light symbolised the loss of both political and human energy. Turner’s sunsets were painted in the studio, whereas the sketchiness of Monet’s View of Rouen (1892) suggests he painted it entirely en plein air. Compared with the Houses of Parliament and San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight (1908) paintings, it is light in touch and palette. These last two works, completed in the studio, seem consciously to rival Turner, who painted both motifs himself.

For Cy Twombly the sun was also an importent motif. The Untitled (Sunset) (1986) works celebrate its power. They stem from a recollection of a late-summer sunset, with its deep reds and fervent yellows mingling with greens and purples suggestive of landscape and flowers. The cooler shades of the Untitled (Porto Ercole) works of 1987 evoke the four elements – earth, fire, wind and water.

The Vital Force

In his later years Turner introduced mythical themes that were both voyeuristic and openly erotic. He showed a sustained interest in erotica in his private sketchbooks. In titillating paintings such as Glaucus and Scylla (1841) and Bacchus and Ariadne (1840), Turner could cloak eroticism in myth.

Glaucus and Scylla and Bacchus and Ariadne both register intense heat, which recurs in Monet’s late paintings of the Japanese Bridge. The dripping paint in these works evokes a womb-like space and the superabundance of flora suggests fecundity. Monet rejected the academic tradition where naked females were depicted in natural settings, but even though there are no nudes in his paintings, they still convey a strong sensuality.

Twombly’s Wilder Shores of Love (1985) and the later Camino Real (II) (2010), make overt reference to sexuality whereas the Untitled paintings (1990 and 1991) echo the abundance of natural energy and ripeness found in Monet’s garden paintings. Sex and eroticism were themes from an early stage in Twombly’s career. Their reappearance in older age testifies, as it does in the work of Turner and Monet, to no diminishment of interest in the vital force.

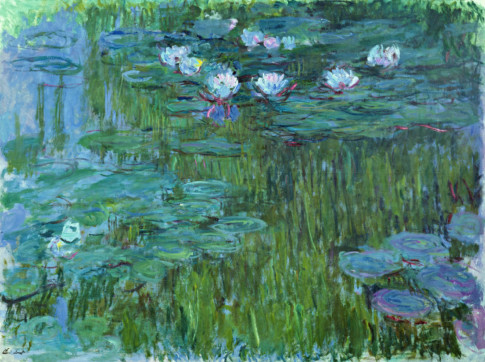

A Floating World

Twombly’s series Blooming: A Scattering of Blossoms and Other Things (2007), appears to depict peonies, most of them past their peak. The red paint trickles down the canvas, like blood or tears. Transience is one of these paintings’ central themes, but they are also hymns to sunlight, sexuality, and generation. This mixture of regret and vitality is also what characterises Monet’s late paintings of the water lily pond. Painted during the First World War and after a period of intense mourning, a sense of human mortality pervades them in contrast to the everlasting endurance of nature. Time appears to stand still in these paintings although intimations of sunlight reflected on the surface of the pond infer the time of day.

Turner’s studies for the Petworth commission make little distinction between water and sky, as all dissolves in the diminishing glow of the sun. The Petworth paintings were completed either shortly before or after his father’s death and the paintings have a certain air of despondency. These images remind the viewer once again of finitude and provide another link to Twombly’s Quattro Stagioni (1993–95), where Et in Arcadia ego, alluding to a tombstone inscription in a painting by Poussin, suggests that death exists even in an ideal world. It is a phrase artists and writers have used for centuries.