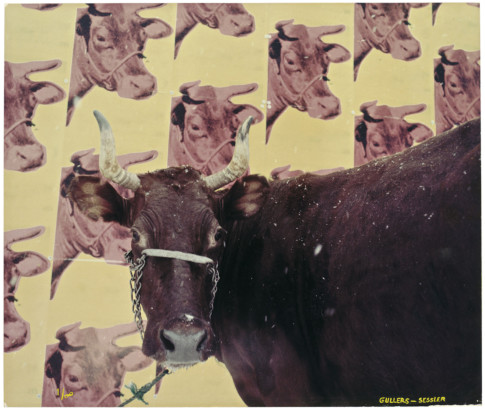

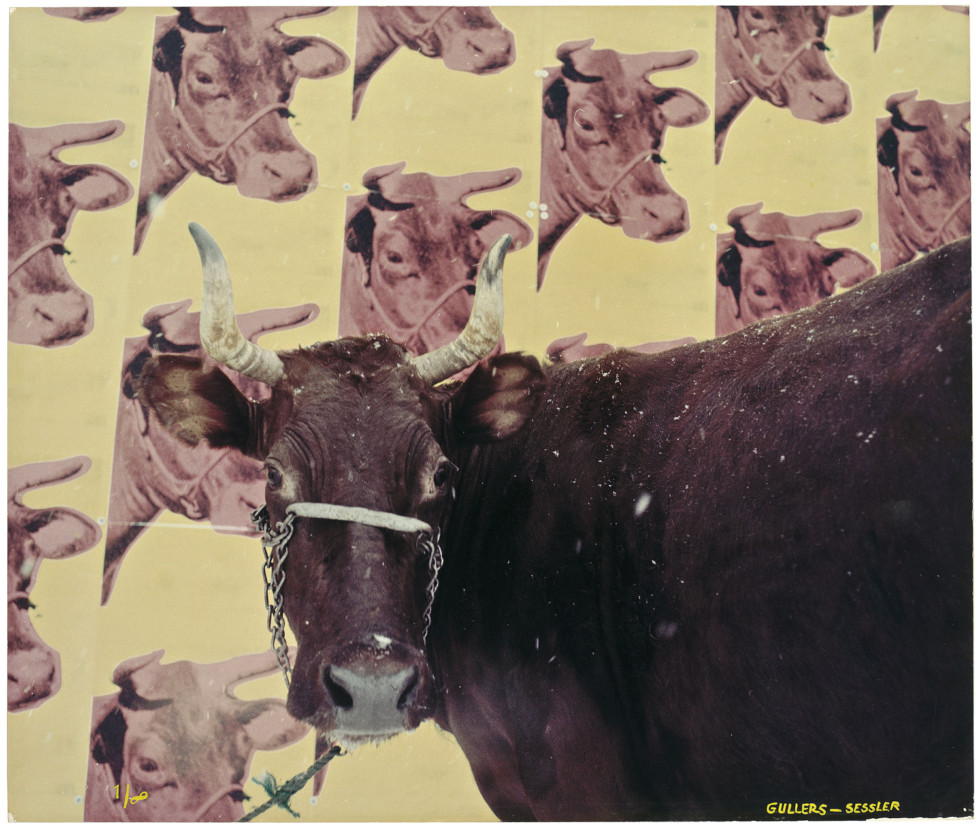

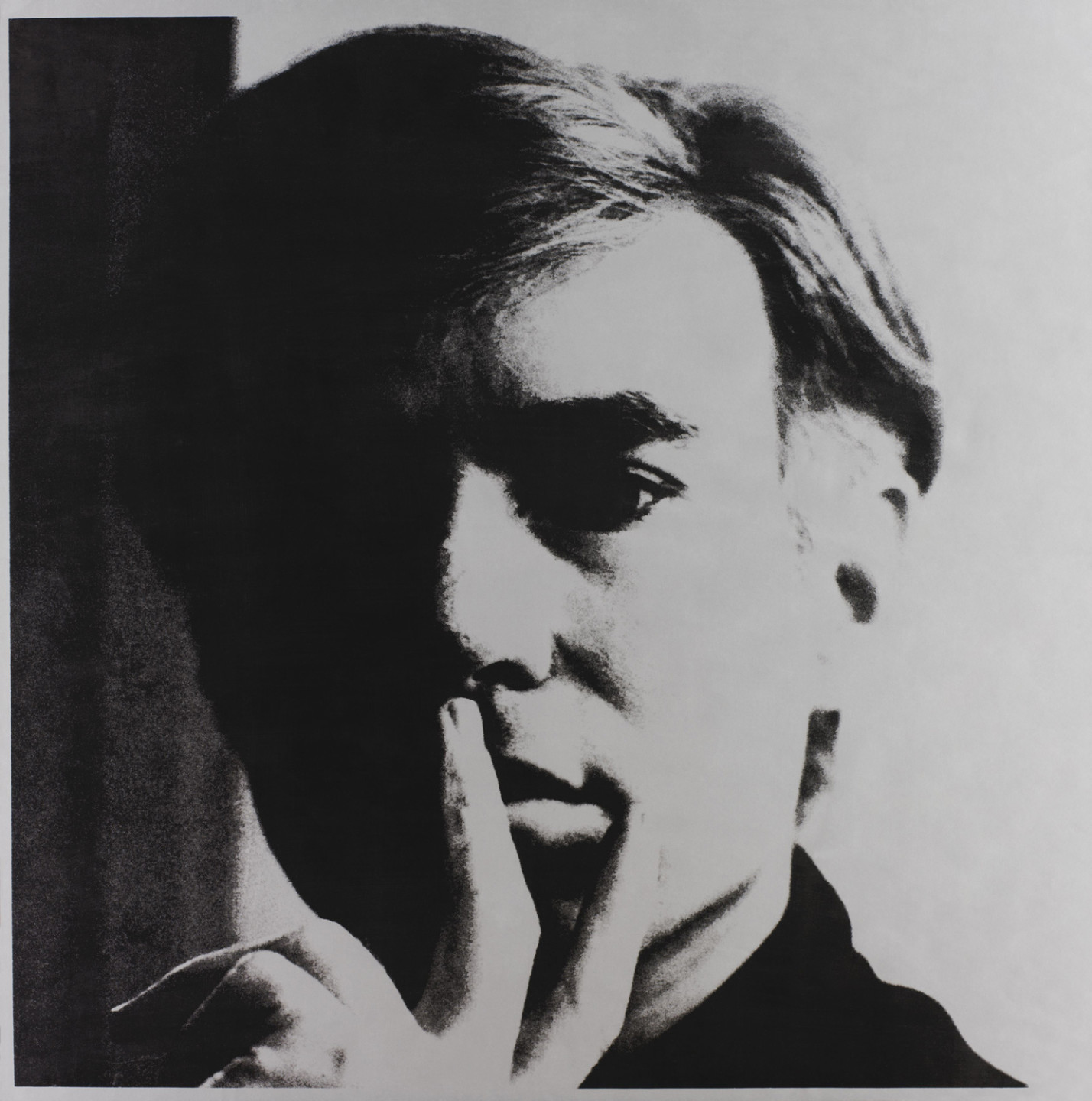

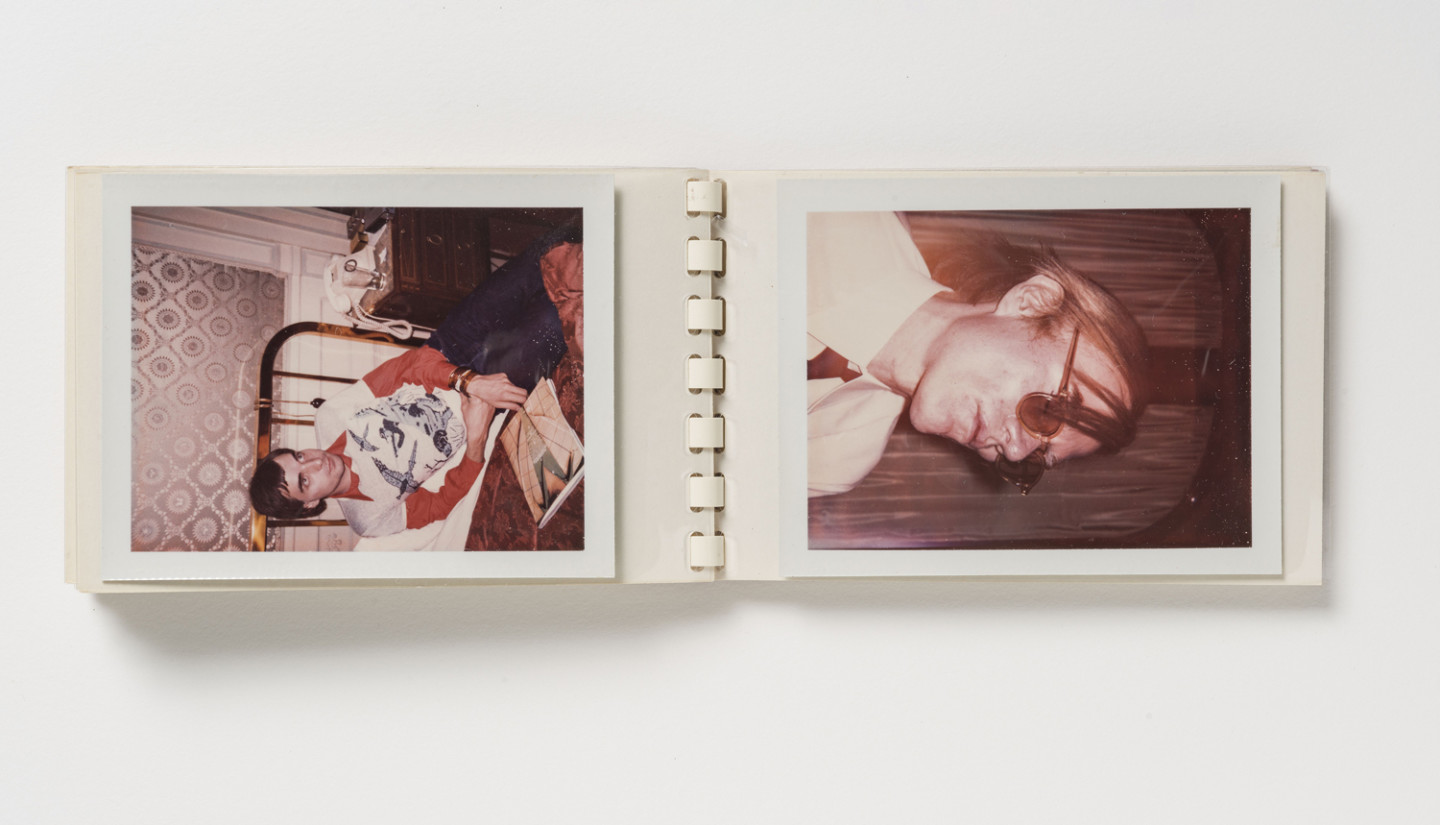

Georg Sessler, Peter Gullers, No title, 1968

Essay by John Peter Nilsson, Curator

Text: John Peter Nilsson

”I think everybody should be nice to everybody”

— Andy Warhol

Spring 1968, just before May

1968 is a legendary year. The Vietnam war, student riots, the assassination of Martin Luther King, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, riots at the Davis Cup in Båstad, the Swedish women’s lib organisation Grupp 8… For some, equality, diversity and solidarity were top of the agenda. For others, 1968 was a year when the dogmatic left was allowed to dominate public debate.

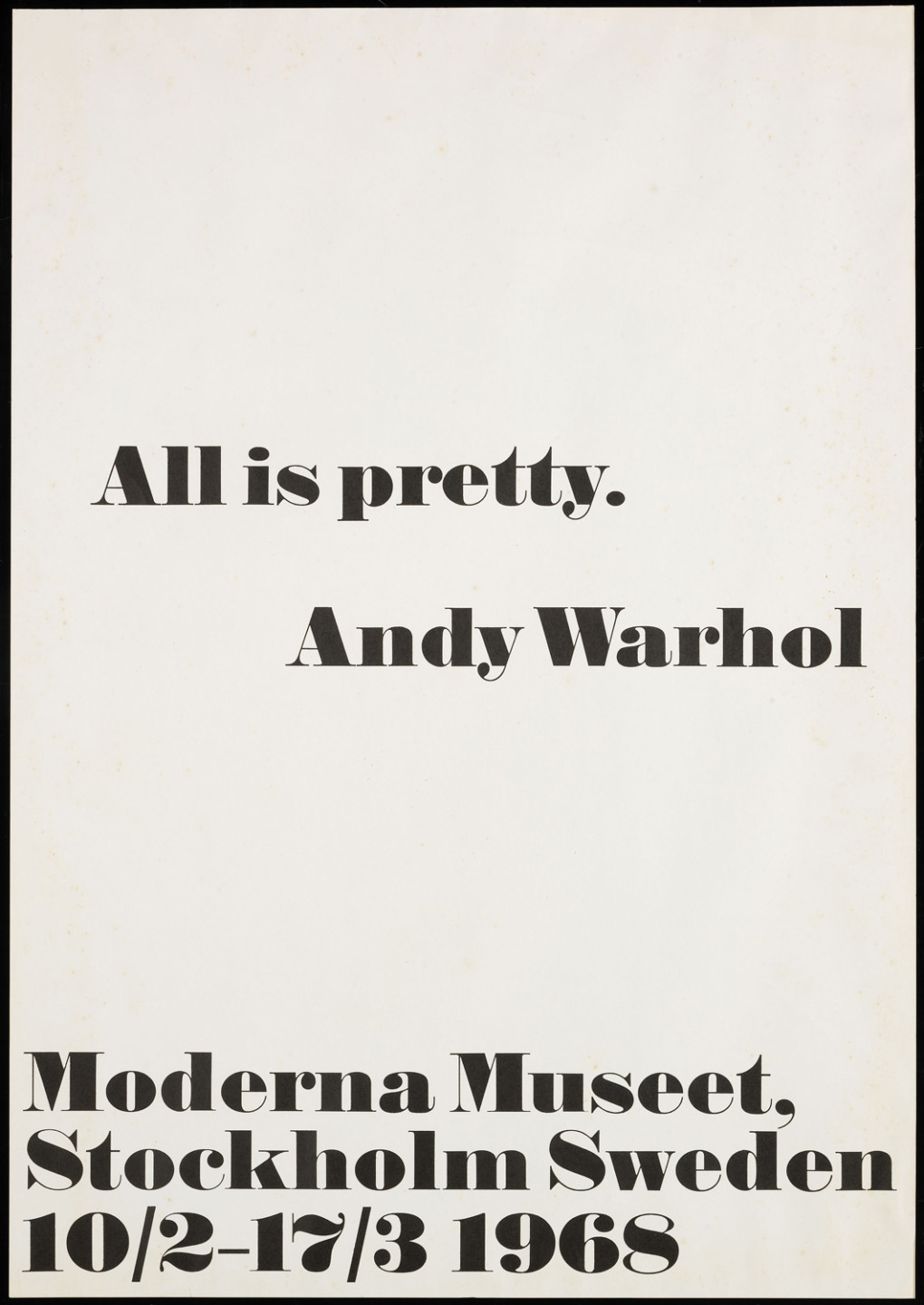

It was also the year Andy Warhol had his very first museum retrospective in Europe, at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, from 10 February to 17 March. In view of the prevailing leftist political climate, one might imagine that the exhibition would be lambasted for being American propaganda – an artist from the capitalist state of USA whose art is based on consumerism and popular culture!

But in Aftonbladet, the Marxist critic Bengt Olvång surprisingly wrote: “We accept an active social critique, one that points at obvious injustices and delivers clear alternatives for action. But the total lack of hope is what frightens us. We want to go on believing that “the American way of life” offers a few human options. We prefer Oldenburg, with his naive delight in plastic objects and his generous warmth for people and their games in this reified society. We feel sympathy for Rosenqvist, who, in the latest issue of Studio International, subscribes to ‘a social realism in blue’. But we can’t deny Warhol his position as an intense, disillusioned truth-seeker.”

In the broadsheet Dagens Nyheter, Ulf Linde was far more dismissive: “As a word loses its meaning if repeated long enough, his images eventually lose any vestige of meaning that they may originally have had. All that remains is ‘superficial’.”

As a word loses its meaning if repeated long enough, his images eventually lose any vestige of meaning that they may originally have had. All that remains is ‘superficial’

Devil or saviour?

In his doctoral thesis ”Euro-Pop: The Mechanical Bride Stripped Bare in Stockholm, Even” (2001), Patrik Andersson posits that Linde’s discontent had started brewing around 1962, when Linde defined “authentic” and “inauthentic” art within the concept of “open art”. The dividing line was drawn between “intuition”, which is European, and “instinct”, which is American, Linde stated. Andersson continues: “As a counter-image to an emasculated American avant-garde tied to concepts of nature and instinct, Linde masculinised a contemporary European avant-garde position by tying it to a social tradition and the more intellectual concept of intuition.”

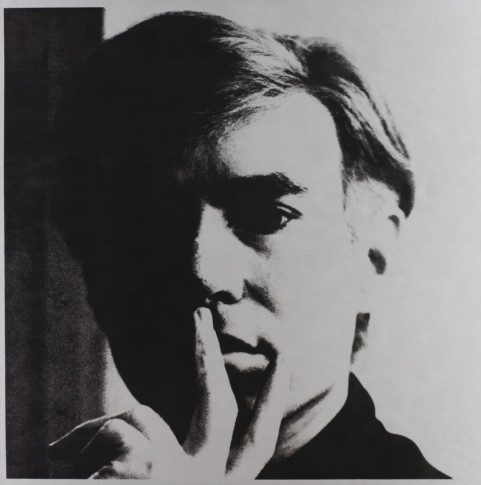

“If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it,” Warhol said about himself. It isn’t hard to imagine that Linde, who believed in intuition as a driving creative force, would be provoked by Warhol’s indifference to the extent that he ended the review above by booming: “Warhol has filled me with distaste.”

“If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it,” Warhol said about himself

In ”Art Press” (2004), the editor in chief Catherine Millet writes that indifference is a key concept of Gnosticism. According to Gnostic ideas, manifested in a variety of religions, the body and being are separate. The body is merely transient, an illusion. For instance, Millet did not regard Warhol’s famous wigs primarily as his trademark but as disguises; he looked like Warhol but was simultaneously someone else. (According to another theory, Warhol was vain and wanted to hide his bald patch…)

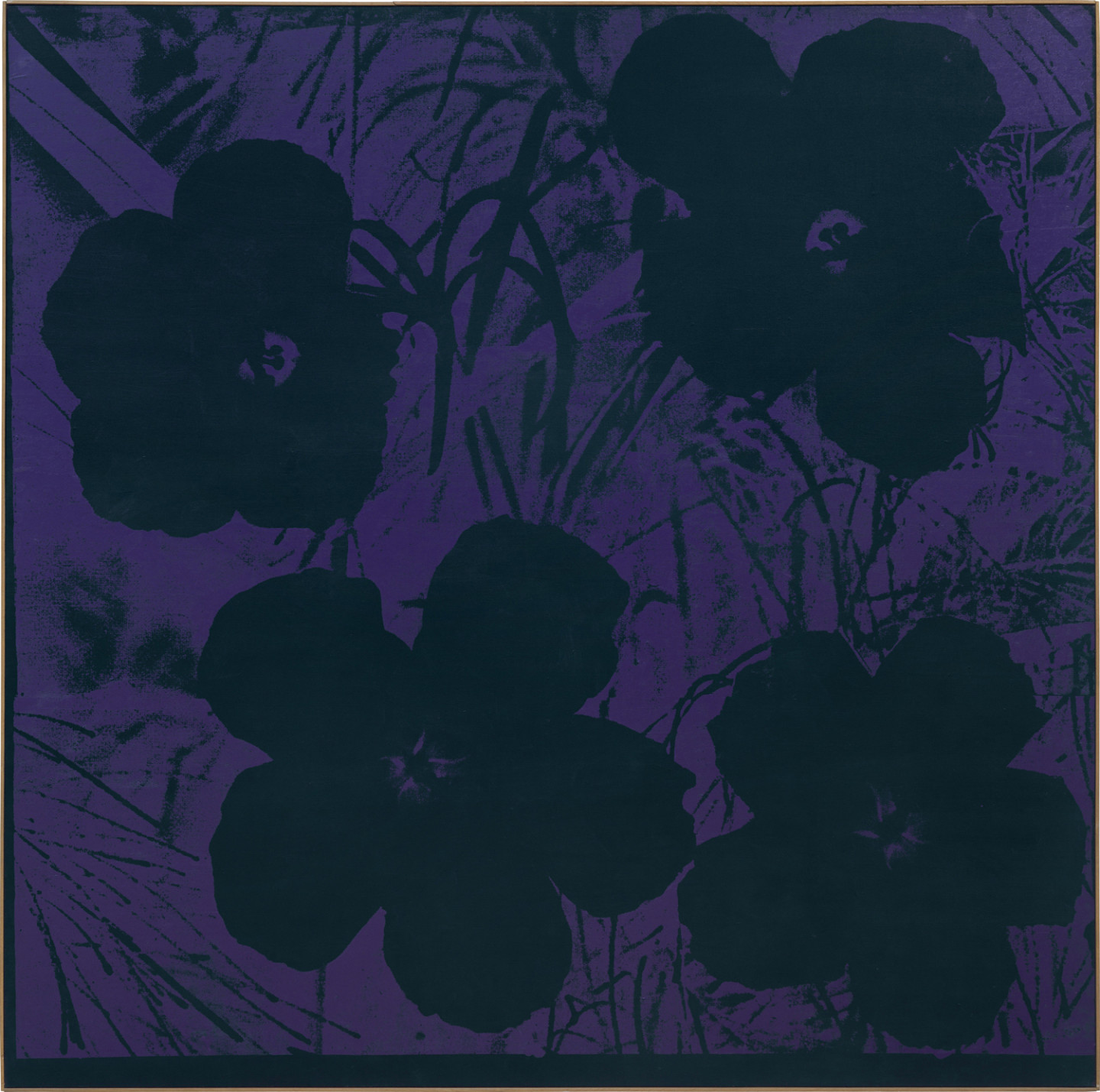

Millet pinpoints the remarkable, ambiguous aura that enveloped Andy Warhol as a person. In Skånska Dagbladet, Per Drougge describes this ambiguity in a different phenomenal way after seeing the exhibition in 1968: “I was seized by great anxiety coupled with a narcotic sense of pleasure by this plethora of murder weapons, suicide portraits, detergent boxes, giant flower, music and Rorschach test-like film stills… Who doesn’t long for grass and cows and milk after being psyched like that!”

Warhol has been called both a devil and a saviour in various contexts. In the song cycle ”Songs for Drella” (1990), Lou Reed and John Cale add another nickname given to him by his “superstar” Ondine: “Drella”, a contraction of “Dracula” and “Cinderella”. But Warhol disliked this moniker. Reed and Cale explain why: “Andy was a Catholic, the ethic ran through his bones / He lived alone with his mother, collecting gossip and toys /Every Sunday when he went to church /He’d kneel in his pew and say, ‘It’s just work, all that matters is work.’”

Apolitical = non-political?

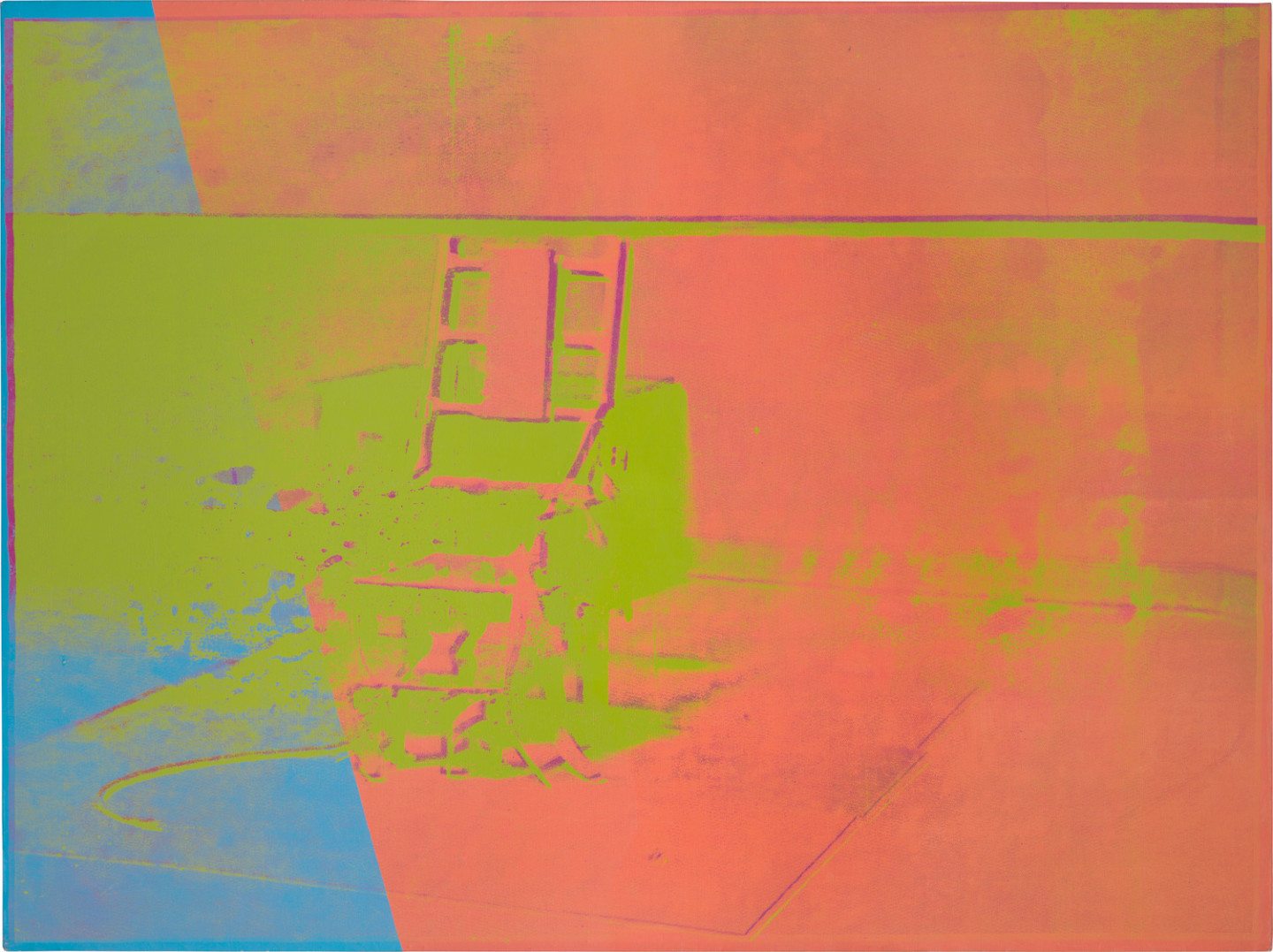

Through the lens of 1968, a political side of Warhol is accentuated, albeit not the one Olvång calls for in his review, “one that points at obvious injustices and delivers clear alternatives for action”. Nevertheless, several art historians have claimed that Warhol was a political artist. In 1972, for instance, he portrayed Richard Nixon in an unsettling way and used the picture as a poster for the Democrats with the text “Vote McGovern”. When the AIDS epidemic was at its worst in the 1980s, Warhol took part actively in the efforts to promote research and prevent rumours from spreading about the disease.

Throughout his career Warhol almost claimed to have no political persuasion or tendencies and his work has repeatedly been interpreted as expressly apolitical. At the same time, however, Warhol, more than any other modernist artist who emerged in the 1960s, dealt with explicitly political and social iconography

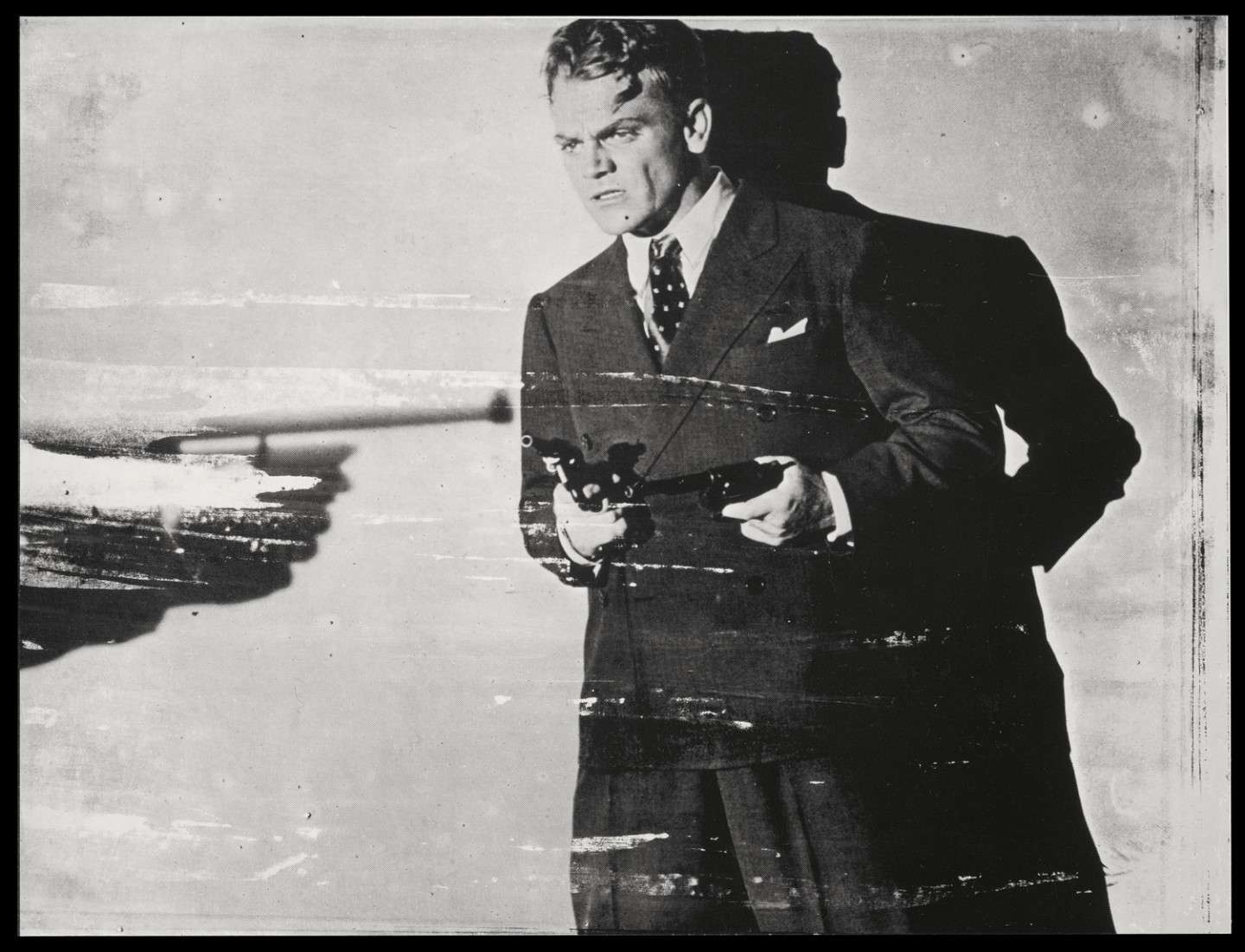

In ”The Art Bulletin” (2001), Blake Stimson writes that Warhol’s indifferent, apolitical stance is a political act in itself: “Throughout his career Warhol almost claimed to have no political persuasion or tendencies and his work has repeatedly been interpreted as expressly apolitical. At the same time, however, Warhol, more than any other modernist artist who emerged in the 1960s, dealt with explicitly political and social iconography: race riots, the death penalty, criminals at large, crowds, political assassinations, and the atomic bomb, all topical and explosive issues; Castro, Mao, Lenin, Che, the hammer and sickle, Nixon, John F. Kennedy and Jackie, Goldwater, all loaded political iconography.”

Stimson continues: “The contradiction between what we might call the apolitical tone and the explicitly political content of his work has posed an on-going problem for critics and historians, leading to interpretations that generally emphasize one side or the other, focusing on Warhol as a thinking, feeling social and political commentator or on Warhol as a numb, affectless machine and a symptom of the flattening out of the economy of the sign. This contradiction or ambivalence need not be taken to be an either/or proposition, however, but instead can be more productively understood to be the core structure of Warhol’s influential aesthetic sensibility.”

1968 was also a turning point for Andy Warhol on a personal level. After losing a script written by the author and feminist Valerie Solanas, she accused him of sabotaging her career. On 3 June, 1968, she fired three shots at him in his studio, The Factory. The first two bullets missed, but the third injured him seriously, and he was pronounced dead at one point but survived. Olle Granath, who assisted Pontus Hultén with the Warhol exhibition in 1968, recalls the incident. In the exhibition catalogue Andy Warhol – Other Voices, Other Rooms (2008), he writes, “After Stockholm, the exhibition travelled to, among other places, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Kunstnerernes Hus in Oslo. It turned out to be a landmark in Warhol’s career, and a roundup of what had passed. After the shooting in Union Square, he was to take a somewhat different path.”

Glamour and melancholy

Warhol became part of the contemporary popular and mass media culture he had previously described in more or less critical terms. In the 1970s, he was New York’s most glamorous celebrity, synonymous with the nightclub Studio 54, and also devised the first advertising campaign for the Swedish state-owned global bestseller Absolut Vodka. He made commissioned portraits of the famous, or the not-so-famous who could afford to pay a lot. His art was a commodity like any other, and his artistic practice grew increasingly speculative.

For the exhibition in 1968, Moderna Museet could not afford to ship Warhol’s own plywood ”Brillo Boxes” to Sweden; instead, 500 original cardboard boxes were delivered straight from the Brillo factory. A few wood copies were also made. This was the start of one of Sweden’s major art scandals, but it also illustrates fundamental postmodern issues.

The story of Warhol’s ”Brillo Boxes”, from the first ones exhibited in 1964 to the ones from 1990, raises questions of original and copy – or what Ulf Linde defined as “authentic” and “inauthentic” art

Three years after Warhol’s death, the former director of Moderna Museet, Pontus Hultén, had 105 Brillo boxes made in Malmö. They were based on the wood boxes that had been made for the exhibition in 1968, which were approved by Warhol. The Malmö boxes became known as “The Stockholm Type” and were said to have been made in 1968. This was challenged, however, and the story of Warhol’s ”Brillo Boxes”, from the first ones exhibited in 1964 to the ones from 1990, raises questions of original and copy – or what Ulf Linde defined as “authentic” and “inauthentic” art.

The documentary film ”Brillo Box (3¢ Off)” (2017) chronicles one “Brillo Box”, bought by American filmmaker Lisanne Skyler’s parents for 1,000 dollars in 1969 and traded two years later. In 2010, the same box was sold at an auction for three million dollars. Skyler not only follows the box’s insane price increase but also gives a picture of the art scene’s complex relationship between commodity and work of art, an aspect that Warhol scrutinised meticulously throughout his artistic career.

His relationship to the art world oscillated between cynicism and melancholy. ”Andy Warhol’s Party Book” (1988), published the year after his death, is symptomatic. It contains photographs and texts from countless parties either hosted or attended by Warhol. Behind the glamorous facade, however, we glimpse another Warhol. In the preface, he writes: “Sex and parties are the two things that you still have to actually be there for – things that involve you and other people. Sex and parties are the two things [where] you still have to […] physically bring your lump of protoplasm and get it close to somebody else’s. To carry on friendships or to cash checks or buy clothes, you can just make a phone call or send a computer message. To give court testimony or look for a date or read your own will after you’re dead, you can send a videotape. To impregnate somebody and reproduce yourself, you can just send sperm. You don’t even have to be there to fight in a war – you just send a bomb. But for sex and parties your body has to be there.”

Before and after 1968

”Warhol 1968” is an exhibition about the exhibition in 1968. It is also an exhibition that reveals the complexity of Warhol’s practice from the landmark year 1968. The period leading up to 1968 Warhol monotonously and indifferently described the emerging American mass media and consumerism in his art. There is nothing behind the surface… But that is not entirely true… Even if he became more commercially speculative after the shooting in 1968, and turned his signature into a trademark, a deceptive ambiguity still lingers in his artistic practice.

Warhol’s statement that we may know more about the world but we still don’t know better, which he enacts by monotonously reproducing the same image in long sequences or by saying that he wishes he were made of plastic or a machine, describes a feeling similar to that of Argullol and Trías.

The booming advertising industry in the early 20th century filled the same purpose as religious art in the 13th century, according to Marshall McLuhan: advertising used the image and its own authority to both create and fulfil people’s desires and persuasions. Warhol had been a practising Catholic since childhood, and McLuhan had converted to the Roman-Catholic faith in his youth. Both have expressed mutual respect for each other, and Warhol was similarly aware of how mass culture was replacing religion in the 20th century. McLuhan, moreover, claimed that mass culture was the polar opposite of the Christian preservation of a private and autonomous metaphysical self. Its position is usurped by capitalism, as the new religion.

“Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art,” Warhol writes in ”The Philosophy of Andy Warhol From A to B and Back Again” (1975). Did Warhol exchange Catholicism for capitalism? The answer is the same as before: what he lets us see is not necessarily what he is, believes in or wants to be.

In the same way that he showed serial pictures of consumer goods and the glitterati alongside death scenes and catastrophes in the 1960s, he comments on the obsession with money and self in the 1970s and 1980s by working simultaneously on series with images of skulls, shadows and urine. Portraits of indigenous Americans are based on Hollywood pictures. Mao, Stalin and Lenin are treated like any other celebrities, and Leonardo da Vinci’s ”The Last Supper” (1495–98) is transformed in Warhol’s version (1986) into a series of 60 reproductions of other reproductions of the original – and with a glimpse of a Honda motorcycle… As Millet suggests in an essay from 2004, Warhol seems to enact his faith like an unruly heretic, regardless of religion, be it Catholicism or capitalism.

His surprisingly many political motifs reduce the grand visions of politics into impossible illusions. He is the disillusioned truth-sayer.

In ”Sette Anni di Desiderio” (1983), Umberto Ecco writes: “Disneyland can allow itself to market its reconstructions as masterpieces of fakery, since the goods that are being marketed are not really reproductions but genuine goods. What is fake is our urge to buy, which we see as real, and in that sense Disneyland is really the quintessence of consumer ideology.”

Like few other 20th-century artists, Andy Warhol portrays a society where everything is for sale and interchangeable. That there is nothing behind the surface need not be a sign of superficiality and cynicism. It could just as well signify emptiness and futility, something that Bengt Olvång understood but Ulf Linde didn’t, in connection with Warhol’s exhibition at Moderna Museet in 1968.

Like few other 20th-century artists, Andy Warhol portrays a society where everything is for sale and interchangeable.

Requiem

From a diary entry dated 27 June, 1983, which Andy Warhol dictated over the phone: “… since the sixties, after years and years and more ‘people’ in the news, you still don’t know anything more about people. Maybe you know more, but you don’t know better. Like you live with someone and not have any idea, either. So what good does all this information do you?”

The point of information is to make us more enlightened as citizens. But is that always the case? The dialogue book ”El Cansancio de Occidente” (1992) with Rafael Argullol and Eugenio Trías presents a gloomy picture: “Passivity is the hallmark of humans today. And it’s clear: if people are turned into spectators and robbed any possibility of influence, this gives rise to a passive being. But all this, of course, takes place under the guise of its opposite. All manner of pseudo-events go on amid a stream of constant activity; activity that reinforces the passive, an uninterrupted motion that fades into immobility. We speak of all the stress and hecticness in our society, but the final impression is of a pursuit of emptiness.”

Warhol’s art will convey the range, power and empathy underlying his transformation of these commonplace catastrophes. Finally, one can sense in this art an underlying human compassion that transcends Warhol’s public affect of studied neutrality.

Warhol’s statement that we may know more about the world but we still don’t know better, which he enacts by monotonously reproducing the same image in long sequences, or by saying that he wishes he were made of plastic or a machine, describes a feeling similar to that of Argullol and Trías. His surprisingly many political motifs reduce the grand visions of politics into impossible illusions. He is the disillusioned truth-sayer. As Walter Hopps writes in the introduction to Warhol’s exhibition ”Death and Disasters” (1988) the year after he died: “Warhol’s art will convey the range, power and empathy underlying his transformation of these commonplace catastrophes. Finally, one can sense in this art an underlying human compassion that transcends Warhol’s public affect of studied neutrality.”

He was presaging the contemporary creative revolution, where the digital user culture is increasingly merged with the assorted offerings of mass culture. Could he predict our self-obsessed, narcissistic era?

In the same way, and long before the selfies and Instagram accounts of today, he documented and preserved everything, be it high or low, through countless photographs, tape recordings, time capsules, etc, presaging the contemporary creative revolution, where the digital user culture is increasingly merged with the assorted offerings of mass culture. Could he predict our self-obsessed, narcissistic era? Or was he simply convinced that even the most trivial or artificial things harboured a divine universe?

John Peter Nilsson

John Peter Nilsson is curator for the exhibition “Warhol 1968”. Since 2004 he has worked at Moderna Museet and has made several acclaimed exhibitions, including “Nils Dardel and Modern Time” (2014–2015), “Dalí Dalí with Francesco Vezzoli” (2009), “SUPERSURREALISMEN” (2012), “The Moderna Exhibition 2006 “and” Olle Baertling – A Modern Classic” (2007). Nilsson was the director of Moderna Museet Malmö in 2012–2016. Between 1986 and 2004, he was a freelance art critic for the Swedish daily Aftonbladet and organised several exhibitions as an independent curator, among others he was curator for The Nordic Pavilion at The Venice Biennale 1999. He has also worked as editor-in-chief for “NU: The Nordic Art Review”, and for “Siksi: The Nordic Art Review “. Since 2017, he works as a Communicative Museum Strategist at Moderna Museet in Stockholm.