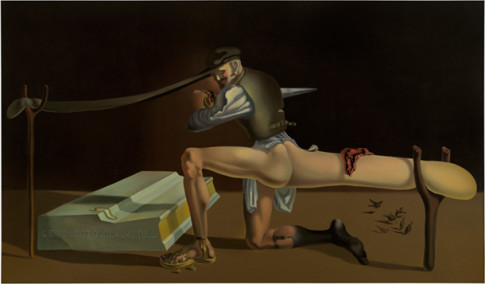

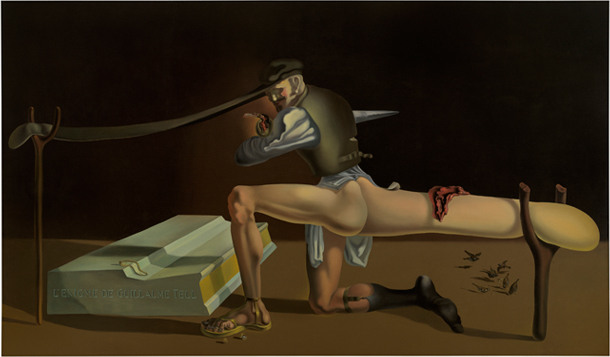

Salvador Dalí, Wilhelm Tells gåta, 1933 © Salvador Dalí, Fundación Gala-Salvador Dali / Bildupphovsrätt 2012

Douglas Coupland about THE SUPERSURREALISM

What is THE SUPERSURREALISM?

On American reality TV shows they’ll sometimes interview a teenager

about something that’s just happened to them on the show …perhaps this

teenager has just finished eating a smoothie made of tropical insects, or

perhaps they’ve just karaoked with Demi Moore. More often than not these

young people will say, “It was so …surreal.” This comes as a shock to

me because these are people who can’t locate France on a world map or

multiply 8 x 7, and yet here they are using the word ‘surreal.’

Awesome — it was so surreal.

So what exactly is it these young people are actually meaning

when they stare at a game show host and say, “Wow, that was so surreal

— I can’t believe I just smashed cantaloupe melons with Grace Jones”?

Traditionally, surrealism is about images and symbols inside our brains

free-associating with themselves without the burden or agenda of day-today

consciousness — not quite a dream state — rather, a recognition that

there are deeper levels of identity available that can be creatively accessed

with the end in mind of crystallizing new and revealing mental states in the

form of an art work or artistic experience.

The collective assumption here is that there actually do exist

deeper and truer versions of ourselves — wiser, truer versions — if only we

could listen attentively enough, we might become better humans, far more

engaged with being alive on the planet, less sexually screwed up, more

fully creative: hence Freud and everything since. But there are potential

errors in this system of thinking.

In Vienna in the mid-1990s I was giving a lecture at the Vienna

Literary Festival, and the theme that year was money. When I came on

stage, I said, “It’s a pleasure to be visiting Vienna, the place where the

subconscious was invented.” I waited a second for that to sink in — there

was a bit of a murmur, at which point I said, “Whoops. What I meant to say

was that it’s a pleasure to be in Vienna, the place where the subconscious

was discovered.” That made everyone quiet and happy; the existence of

the subconscious was nonnegotiable. Later in that same talk I mentioned

how the subconscious is actually a lot like Antarctica: it’s huge, we know

very little about it, it’s incredibly hard to reach and it can only be visited

with lots of money. Rather than getting a chuckle, people rubbed their

chins and made body language to the effect of, “This Canadian writer chap

has made a very good point. Bravo.”

After Vienna that I began thinking about the subconscious on

a scientific level: id, ego and super-ego. But why just the three levels?

Maybe there are six levels of self. Or a few hundred. Or an infinite number.

To date I’ve read no satisfying scientific reason to assume a mere three

levels of self. It may well be true; I just don’t believe it. It’s things like SSRI

antidepressants and other pills developed in the last two decades that

makes me wonder if the psyche is infinitely layered and ever evolving.

Concepts change. An example? We once believed that as adults we had

all the brain cells we’re ever going to have inside our skulls, and that from

puberty on, we can only lose them. But no, we all grow about 10,000 new

cells a day, with the caveat that unless we use them, these new cells are

reabsorbed back into the body (which is kind of surreal.) Serves us right

for not using them.

But here I’ve only discussed levels of self and identity looking inward.

What makes 2012 so much more interesting than 1912 is that we now have

this thing called the Internet in our lives, and this Internet thingy has, in the

most McLuhanistic sense, become a true externalization of our interior selves:

our memories, our emotions, so much of our entire sense of being and

belonging. The Internet has taken something that was once inside us and put

it outside of us, has made it searchable, mashable, stealable and tinkerable. The Internet, as described by William Gibson, is a massive consensual

hallucination, and at this point in history, not too many people would disagree.

But let’s go back in time a few decades. Let’s go back to 1981,

my second year in art school, pre-Prozac, pre-personal computer

pre- many things. I remember being told by instructors that changing

the channels on a TV set just to see what juxtapositions it throws

back at you was postmodern because one wasn’t dealing with a true

subconsciousness here, it was a pseudoconsciousness, and therefore

not interesting. I disagreed violently, and continue to violently disagree

with this assumption. It presupposes an inability of human consciousness

to expand outside of itself; Greece and Rome had civilizations, and

Vancouver in 1981 had changing TV channels; older civilizations may be

more glamorous and enduring, but ontologically, they’re no different than

TV channel changes. TV is ephemeral; the Coliseum is concrete but still

corroding; it’s only a matter of time frames. Collective manifestation of the

inner world can, and does, take infinite forms.

Which gets us back to surrealism proper, and it gets us back

to teenagers on US TV saying, “Wow, man, that was the most surreal

experience.” What these teenagers are alluding to, it seems to me, is that

their psyches have been put through an external identity randomizer —

they’ve been pulled through the churn. The game show or reality show

or what have you, has taken the teenager on a tour through externalized

layers of reality that are utterly new since 1912, 1981 or even 2000.

Their psyches have been whisked through the collective dream and

the collective subconsciousness, yielding just the same sorts of tingly

sensations one might have had looking at a Dali or a Magritte in the 1920s

or 1930s.

It’s also important to remember that Surrealism was a movement.

In the early 20th century, movements lasted decades. By the sixties they

lasted two years. Nowadays we don’t even have movements; we have

memes. Memes last a day or two and then vanish. Were surrealism to

have been invented today, it’s be a very cool web site that throws images

and clips together and makes your head feel tingly. “Have you gone to

supersurrealism.com? It’s like a Japanese TV game show except it’s for

real and it’s exploding right in front of your face. It’s totally supersurreal.”

Douglas Coupland