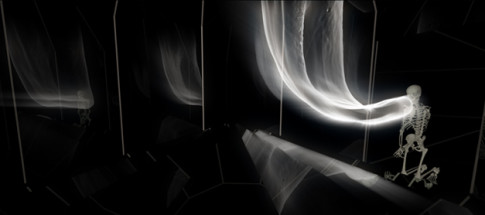

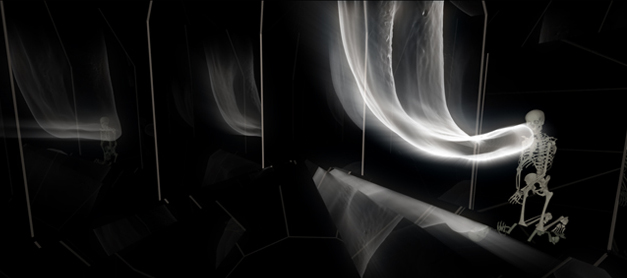

Magnus Wallin, MISSION, 2009 © Courtesy of Galerie Nordenhake, and Elastic Gallery

John Peter Nilsson about THE SUPERSURREALISM

In his Surrealist Manifesto from 1924, André Breton writes that “the realistic attitude, inspired by positivism, from Saint Thomas Aquinas to Anatole France, clearly seems to me to be hostile to any intellectual or moral advancement. I loathe it, for it is made up of mediocrity, hate and dull conceit. It is this attitude which today gives birth to these ridiculous books, these insulting plays. It constantly feeds on and derives strength from the newspapers and stultifies both science and art by assiduously flattering the lowest of tastes; clarity bordering on stupidity, a dog’s life.”

Couldn’t this just as well have been written today? I interpret Breton’s disgust with realism and its insistence on one absolute truth as a challenge to the individual to free his or her own personal uniqueness. We are all different. Imagination – our ability to confabulate and dream (both waking and sleeping, intoxicated and sober) – is a creative tool that enhances our understanding and experience of life. Admittedly, Breton and Salvador Dalí were estranged over the definition of surrealism, and Dalí was ostracised by the original group of surrealists more or less by choice. Nevertheless, Dalí possibly delivered the best summary of the surrealist creed: “When I look at the starry sky, I find it small. Either I am growing, or else the universe is shrinking. Unless both are happening at the same time.” The world did not afflicted the surrealists, but the surrealists that afflicted the world.

SUPERSURREALISM is an experimental presentation. In a way, we are expanding the surrealist concept. The core of the exhibition consists of works from the Moderna Museet collection. But works have also been borrowed from other institutions, or recently acquired from artists. In 1913, Gertrude Stein wrote, “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.” Perhaps SUPERSURREALISM could be described as a surreal exhibition on surrealism?

The exhibition consists of three parts: Before, During, and After. The Before part covers approaches that playfully challenge the renaissance insistence on common sense and clarity, along with images of Rome, the City of Cities, emerging like a mirage beyond time and space. Together with spiritist experiments and the symbolist attempts to consolidate conflicting emotions and experiences, we present some of the forerunners and sources of inspiration behind the appearance of surrealism in art history from the 1920s and onwards.

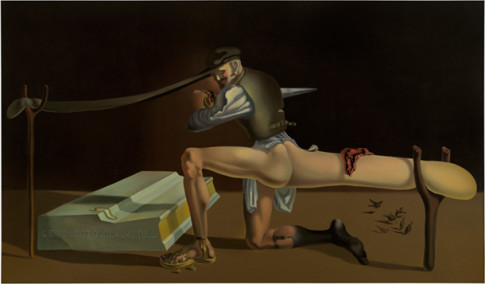

The During section obviously covers classic surrealism. Moderna Museet has a fabulous collection of surrealist works, with practically all the major artists from the crucial period leading up to the Second World War. We are proud to present this collection unconditionally in its entirety here at Moderna Museet Malmö.

But has the influence of surrealism really waned? As a movement in art history, yes. But surrealism is more than a movement in art. It has also become a general concept, representing something inexplicable, that which is recognisable yet strange. Quite simply, something weird. Or, as Douglas Coupland writes: “On American reality TV shows, they’ll sometimes interview a teenager about something that’s just happened to them on the show … perhaps this teenager has just finished eating a smoothie made of tropical insects, or perhaps they’ve just karaoked with Demi Moore. More often than not these young people will say, ‘It was so… surreal.’ This comes as a shock to me, because these are people who can’t locate France on a world map or multiply 8 x 7, and yet, here they are using the word ‘surreal’.”

It is still possible even today to identify surrealist influences in contemporary art. Or perhaps our everyday life itself is actually surrealistically-tinged? Marshall McLuhan said that media society can be seen as an extension of man’s central nervous system. The vast influence of the mass media on our world view and ourselves can be seen as a hallucinatory dream state where facts and lies get mixed up on our journey through time and space without really moving, seated as we are in front of a TV or computer.

“The forms of Surrealist language adapt themselves best to dialogue,” André Breton writes in his Manifesto. “Here, two thoughts confront each other; while one is being delivered, the other is busy with it – but how is it busy with it?” More than 80 years later, Breton’s seed of a thought has sprouted a global jungle: “I remember being told by instructors that changing the channels on a TV set just to see what juxtapositions it throws back at you was postmodern because one wasn’t dealing with a true subconsciousness, it was a pseudoconsciousness, and therefore not interesting. I disagreed violently,” writes Douglas Coupland, “and continue to violently disagree with this assumption. It presupposes an inability of human consciousness to expand outside itself.”

If SUPERSURREALISM has a message it would be a belief, or rather, a confidence – however naive, silly, obscure or incongruous – that nothing is in vain. Everything can be used and regarded as an experience. Breton, Dalí and all the groundbreaking surrealists envisaged a world where the (sub)conscious could have a decisive influence. This is the reality of today’s online media-world. Everyone can communicate with anyone or no one, any time. Our collective subconscious is no longer limited to the individual. Linked to the satellites, it is a new kind of organism, slick and slippery. It is an internet that reflects all the desires and limitations a human being can be imagined to express. From that perspective, art is paltry. Perhaps lost. All that remains is nostalgia.

John Peter Nilsson