A voyage inside a frame

A VOYAGE INSIDE A FRAME

Karin Mamma Andersson

I don’t remember exactly when I first raised my eyebrows at Dick Bengtsson’s work.

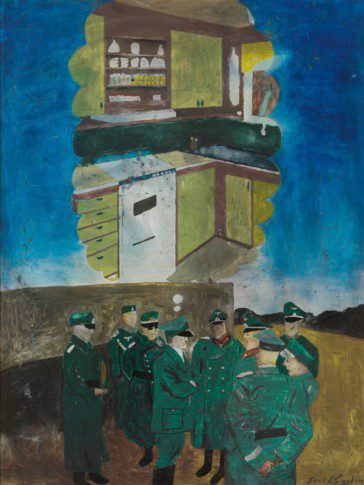

It must have been some time in the mid-1980s, when I was working as a museum guard at Moderna Museet, the Östasiatiska Museet and Nationalmuseum. Some of his paintings that are in the Moderna Museet collection were hanging on the screens that could be pulled out near the bookshop. When the museum was quiet, we used to entertain ourselves with taking a closer look at Jan Håfström’s Grandmother, Ola Billgren’s A Mediterràneo, or Dick Bengtsson’s Protest March. As a sort of consolation for the fact that I was working as a guard instead of painting, I used to buy cards and catalogues. One of these was a small book on Dick Bengtsson’s works.

That catalogue was to become exceedingly important to me, even while I was still at art college. For many years, I would start my working day with a cup of coffee and a look in the dog-eared catalogue from Moderna Museet, 1983. It is hard to pinpoint exactly what it was I found so captivating. One thing is for certain: It was refreshing to encounter an oeuvre that was so unprestigious, independent and entirely unsentimental. Painting upon painting produced in an unflowing, slow and eerily beautiful way. Suddenly, everything was permissible and pardoned, all you had to do was paint and trust your innermost dreams and nightmares. I got the feeling that he couldn’t care less about the established rules for painting and had complete confidence in himself.

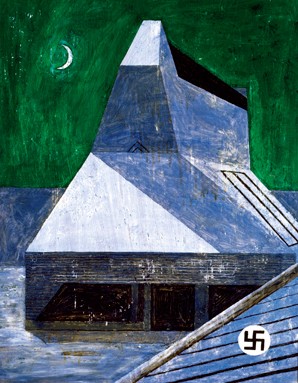

In spring 1988, I had stopped working as a guard and was instead mowing the lawn in Paradise. Lars Nittve was just filling out some papers on my behalf in his office and I saw the Domburg Suite on his wall. I reacted to the politically explicit church and swastikas. How religion, culture and power were intertwined.

Was Dick’s painting a description of Mondrian’s development as an artist? Or was the Suite merely a reflection on what modernism stood for?

The swastika appears in many of his paintings, and is always as deeply disconcerting. But Dick was not alone in working with political metaphor. On the contrary, many artists were doing that in the 1970s – possibly as a way of remaining in contact with the undercurrent of the time.

I see parallels to several of his peers, for instance Bruno Knutman and Sverker Broström. Although I find both artists interesting, neither has touched me as profoundly as Bengtsson. There is an odour of ashtray and sweat, and this is hardly a sunny painter we are dealing with; sooty, more like it. It is impossible to place him, and a venture into his domain is a reckless adventure. But it is a voyage within a frame. And yet, he appears entirely open and illogical in his subject matter, often splitting up the composition in a veritably amateurish manner, sort of like a child, but not at all naivist.

As a draughtsman he has a unique style. I am referring, of course, to the drawings in the paintings. Anyone who is familiar with his works will recognise Bengtsson in a flash. In the way he draws a mountain, a leg, a palm tree or a diving board.

Eclectic or traditionalist? Obviously, he is both. For me, his approach helped legitimise my own. Borrowing and lending, mixing up to see what happens. A kind of unstructured echo of history, where high and low play on equal terms. Constant attempts to portray reality in a way that is not subordinated to reality.

The painting Early Sunday Morning is one such typical play with history. Edward Hopper’s painting with the same title is painted after a stage set which, in turn, was probably copied from a photo. It’s like a game of Chinese Whispers.

This approach is nothing new in itself. Artists have done this throughout the ages. Working from originals is virtually unavoidable unless you choose to work only from “life”. The problem is that there is often an impending danger when you base your work on originals. What was initially a starting-point and an asset to the work can suddenly become something you daren’t depart from or liberate yourself from.

Dick Bengtsson’s Protest March is similar to the cover of the publication Bondetåget from 1914. The cover shows four symbols, one in each corner. In the lower left-hand corner is a swastika. Was this the image that set the whole swastika idea going? I found this publication in a bookseller’s on Gotland some seven years ago. To be honest I was a bit surprised to see how faithfully he had stuck to the original.

When I see exhibitions, I’m always interested in studying how the pictures are made. How the paint was applied, what brushes and varnishes were used and what material they were painted on. I feel that part of the story lies in the materials, and in this respect Dick Bengtsson is outstanding.

When I was an art student I used to think his methods were odd. For instance, I had heard that he used an iron to achieve certain finishes. I tried it myself, but the paint usually stuck to the iron, and if it didn’t the surface cracked.

I am sitting here again, browsing through the dog-eared catalogue from 1983. It feels rather strange, the charge is no longer as strong. The painting I kept going back to was Mountain Hikers (Bergsvandrare). It haunted me for many years. I couldn’t leave it, and eventually it felt like it was mine. I’ve painted so many details from it and often wondered where the people in the picture were heading.

At art college I painted a lot of landscapes, both in nature and in my studio. Apart from Bengtsson, I studied Corot, Hill, Josephson, Munch, Osslund and Gauguin. All these artists are manifest in Mountain Hikers.

Many years passed before I saw the painting in real life. The first time was at Liljevalchs konsthall, where it was included in an exhibition of art owned by the City of Stockholm and Stockholm schools.

I realised that the colours in the reproduction I’d pored over for so long were all wrong. The painting is much greener in reality, but I still prefer the erroneous version in Moderna Museet’s catalogue. That’s the version I feel most at home with.

Over the years, I’ve found photos now and then which I believe may have inspired various paintings by Dick – some of which may have been used for Mountain Hikers. The boy in the centre is probably from a book about Hälsingland, not such a farfetched idea, considering that Bengtsson lived periodically in Voxna. The blond girl at the back could be me. For many years now, I’ve been going on mountain hikes, most recently in the Alps. It’s boring walking behind someone and just seeing the shoes and back of the person in front of you. Sometimes this is necessary if you don’t know the way, but if you know where you’re going it’s infinitely more thrilling to walk alone. In conclusion, I would say that it has been a pleasure to follow so brilliantly sharp an artist as Dick Bengtsson. No one can solve his riddles, he is unfathomable.