Why did Dick Bengtsson paint swastikas?

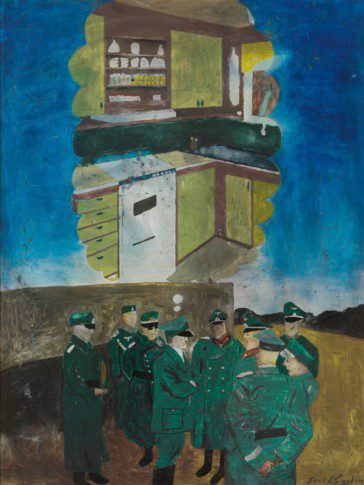

He was born in 1936 and grew up in a nation that is still clamouring to be considered a neutral country full of “good” Swedes, a country far removed from the realities of the Holocaust and the Second World War. Like no other artist, Dick Bengtsson creates subtle short-circuits between functionalism and fascism, between the idyll of red cottages and the brown-shirted ideals of purity, between the blond 1930s Hitler Youth and abstract painting. He alludes to a kinship between authoritarian religious practices and the totalitarian inclinations of modernism. In an interview in 1983, he says, “My pictures are largely about forged reality, about the idyll that is not what it appears to be.”

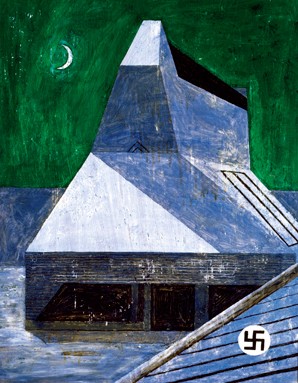

Many of his paintings feature swastikas, instigating furious discussions and physical assaults. In his diptych Hat & Cap Factory, the entire motif is reversed, with one exception – the swastika in the lower corner of the paintings is the same in both pictures, regardless of outlook. In the Domburg Suite the artist has copied a series of paintings by Mondrian. It starts with a picture representing a cathedral and mutates into an abstract black composition, a reversed swastika.

Dick Bengtsson’s art is ambiguous. It delivers no unequivocal message, no simple answers. On the contrary, it seeks out the grey zones and the minefields, where ideologies are revealed and apparently innocuous facades are torn down. Why does his work provoke such strong feelings today? Is it because he does not state his intentions explicitly, or is it because he forces the viewer to take a stand.

Guest curator

One possible explanation to these odd elements in the paintings is that Dick Bengtsson used swastikas, among other things, to challenge our way of seeing. By imposing the swastika in certain paintings, he added a dynamic that only a symbol as charged as this can arouse. No one can simply remain unperturbed by a painting with a swastika. Since Bengtsson himself refused to explain his paintings, however, we can only speculate about the meaning and purpose of his works.

One thing is certain, however: this tainted Nazi symbol effectively breaks up the stillness of the paintings and alludes to the darker undercurrents that are a constant threat to our democratic society. Bengtsson used the symbol to add an uncomfortable element to the cracked surface of the paintings. His intention was probably also to show how time and history influence our interpretation. Before the Nazi atrocities, the swastika, as we know, was an ancient religious symbol for the sun, without political implications; now it is perhaps our most stigmatised symbol, and as such, it is a gratifying object for an artist’s scrutiny.

Dick Bengtsson was obviously not a Nazi; on the contrary, he was an artist who refused to turn a blind eye to disturbing and complex factors, and who showed us in practice that colour, shapes and composition always, in one form or another, convey meaning.